Understanding the Incentives of Commissions Motivated Agents:

Theory and Evidence from the Indian Life Insurance Market

Santosh Anagol

Wharton

Shawn Cole

Harvard Business School

Shayak Sarkar

∗

Harvard University

January 2, 2012

Abstract

We conduct a series of field experiments to evaluate two competing views of the role of

financial service intermediaries in providing product recommendations to potentially uninformed

consumers. One view argues intermediaries provide valuable product education, and guide

consumers towards suitable products. Consumers understand how commissions affect agents’

incentives, and make optimal product choices. The second view argues that intermediaries

recommend and sell products that maximize the agents’ well-being, with little or no regard for

the customer. Audit studies in the Indian life insurance market find evidence supporting the

second view: in 60-80% of visits, agents recommend unsuitable (strictly dominated) products

that provide high commissions to the agents. Customers who specifically express interest in a

suitable product are more likely to receive an appropriate recommendation, though most still

receive bad advice. Agents cater to the beliefs of uninformed consumers, even when those beliefs

are wrong.

We then test how regulation and market structure affect advice. A natural experiment that

required agents to describe commissions for a specific product caused agents to shift recom-

mendations to an alternative product, which had even higher commissions but no disclosure

requirement. We do find some scope for market discipline to generate debiasing: when auditors

express inconsistent beliefs about the product suitable from them, and mention they have re-

ceived advice from another seller of insurance, they are more likely to receive suitable advice.

Agents provide better advice to more sophisticated consumers.

Finally, we describe a model in which dominated products survive in equilibrium, even with

competition.

∗

[email protected]enn.edu, scole@hbs.edu, and ssark[email protected]ard.edu. iTrust provided valuable con-

text on the Indian insurance market for this project. We also thank Daniel Bergstresser, Sendhil Mullainathan, Petia

Topalova, Peter Tufano, Shing-Yi Wang, Justin Wolfers, and workshop participants at Harvard Business School,

Helsinki Finance Summit, Hunter College, the ISB CAF Conference, the NBER Household Finance Working Group,

the NBER Insurance Working Group, Princeton, the RAND Behavioral Finance Forum, and the Utah Winter Fi-

nance Conference for comments and suggestions. We thank the Harvard Lab for Economic and Policy Applications,

Wharton Global Initiatives, Wharton Dean’s Research Fund, Wharton Risk Management and Decision Processes

Center, and the Penn Lauder CIBER Fund for financial support. Manoj Garg, Shahid Vaziralli and Anand Kothari

provided excellent research assistance.

1

1 Introduction

The recent financial crisis has spurred many countries to pursue new consumer financial regulations

that could drastically change the way household financial products are distributed. Both Australia

and the U.K. Financial Services Authority have announced bans, to take effect in 2012, on the

payment of commissions to independent financial advisors.

1

And as of August 2009, the Indian

mutual funds regulator banned mutual funds from collecting entry loads, which had previously

primarily been used to pay commissions to mutual fund brokers.

2

Opponents of these bans argue

that commissions are important to motivate agents to provide financial advice and customer edu-

cation, that competition and reputation concerns will discipline agents, and that consumers have

demonstrated little willingness to pay for independent financial advice.

There is very little evidence to inform these important policy questions. In this paper, we

use a set of field experiments conducted in the Indian life insurance market to provide quantitative

evidence on the quality of advice provided by commissions motivated agents. In addition, we

test recent theories on how commissions motivated agents will respond to disclosure requirements,

greater competition, or more sophisticated consumers.

We focus on the market for life insurance in India for the following reasons. First, given the

complexity of life insurance, consumers likely require help in making purchasing decisions. Sec-

ond, popular press accounts suggest the market may not function well: life insurance agents in

India engage in unethical business practices, promising unrealistic returns or suggesting only high

commission products.

3

Third, the industry is large, with approximately 44 billion dollars of pre-

miums collected in the 2007-2008 financial year, 2.7 million insurance sales agents who collected

approximately 3.73 billion dollars in commissions in 2007-2008, and a total of 105 million insur-

ance customers. Approximately 20 percent of household savings in India is invested in whole life

insurance plans (IRDA, 2010). Fourth, agent behavior is extremely important in this market, as

approximately 90 percent of insurance purchasers buy through agents.

1

Independent Financial Advisors received commissions to sell mutual funds and life insurance products. See

Reuters (2009), Vincent (2009) and Dunkley (2009) for more information on the U.K. ban on commissions. See

“Australia Proposes Ban on Commission” in the Financial Times, September 4, 2011.

2

For newspaper accounts of the importance of entry loads as the primary source of commissions see (1) “MFs

Look For Life Beyond Entry Load Ban,” Times of India, July 19, 2010 (2)“Mutual Fund Industry Struggling to Woo

Retail Investors,” Business Today, February 2011 Edition.

3

See for example, “LIC agents promise 200% return on ’0-investment’ plan,” Economic Times, 22 February 2008.

2

Lastly, commissions motivated sales agents are of particular importance in emerging economies

where a large fraction of the population has little or no experience with formal financial markets.

Commissions may motivate agents to identify potential consumers, educate them about the range

of available products, and identify the most suitable products. Opponents, however, argue that the

commissions motivated agents will encourage consumers to purchase expensive, complicated prod-

ucts that are not necessarily welfare maximizing for households. Systematic empirical evidence is

needed to inform the policy debate about whether commissions motivated agents are necessary for

encouraging the adoption of complicated household financial products.

This project consists of three closely related field experiments. All of these experiments use

an audit study methodology, in which we hired and trained individuals to visit life insurance agents,

express interest in life insurance policies, and seek product recommendations. The goal of the first

set of audits was to test whether, and under what circumstances, agents recommend products

suitable for consumers. In particular, we focused on two common life insurance products: whole life

and term life. We chose these two products because, in the Indian context, consumers are generally

much better off purchasing a term life insurance product than whole life. In section II, we detail

how large this violation of the law of one price can be. The combination of a savings account and

a term insurance policy can provide over six times as much value as a whole life insurance policy.

An important source of friction in financial product markets is that consumers may not know

which products are best for them. A range of evidence suggests that individuals with low levels of

financial literacy make poor investment decisions (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2007). An important role

of agents may be to identify suitable products. In our first experiment, we randomly vary both the

stated belief of the customer as to which product is most suitable, as well information the client

provides about his or her actual needs. Thus, we have some treatments where the customer has

an initial preference for term insurance but where whole insurance is actually the more suitable

product, and vice versa (whole insurance could be a suitable product for an individual who has

difficulty committing to saving). If an agent’s role is to match clients to suitable products, only

the latter information should affect agent recommendations. In fact, we find agents are just as

responsive to consumers self-reported (and incorrect) beliefs as they are to consumers needs.

Interestingly, this is true even when the commission on the more suitable product is higher,

and hence the agent has a strong incentive to de-bias the customer. We view this result as important

3

because it suggests that agents have a strong incentive to cater to the initial preferences of customers

in order to close the sale; contradicting the initial preference of customers, even when they are

wrong, may not be a good sales strategy. Thus, salesmen are unlikely to de-bias customers if they

have strong initial preferences to products that may be unsuitable for them.

Our second, third, and fourth experiments test predictions on how disclosure, competition,

and increased sophistication of consumers affect the quality of advice provided by agents.

In our second experiment, we study whether competition amongst agents can lead to higher

quality advice. We find that that agents who face greater competition, which we induce by having

our auditor state that they have already talked to another agent, leads to better advice. This

evidence is consistent with standard economic models which suggest that, at least under perfect

competition, agents will have an incentive to provide good advice.

In our third experiment we test how disclosure regulation affects the quality of advice provided

by life insurance agents. Mandating that agents disclose commissions has been a popular policy

response to perceived mis-selling. In theory, once consumers understand the incentives faced by

agents, they will be able to filter the advice and recommendations, improving the chance they choose

the product best suited for them, rather than the product that maximizes the agents commissions.

We take advantage of a natural experiment: as of July 1, 2010, the Indian insurance regulator

mandated that insurance agents disclose the commissions they earned on equity linked life insurance

products. We have data on 149 audits conducted before July 1, and 108 audits conducted after

July 1. We find that following the implementation of the regulation, life insurance agents are much

less likely to propose the unit-linked insurance policy to clients, and instead recommend whole life

policies which have higher, but opaque, commissions.

In our last experiment, we test whether the quality of advice received varies by the level of

sophistication the clients demonstrate. We find that less sophisticated agents are more likely to

receive a recommendation for the wrong product, suggesting that agents discriminate in the types

of advice they provide. This result suggests that the selling of unsuitable products is likely to have

the largest welfare impacts on those who are least knowledgeable about financial products in the

first place.

This paper speaks directly to the small, but growing, literature on the role of brokers and

financial advisors in selling financial products. This literature is based on the premise that, in

4

contrast to the market for consumption goods such as pizza, buyers of financial products need

advice and guidance both to determine which product or products are suitable for them, and to

select the best-valued product from the set of products that are suitable.

The theoretical literature can be divided into two strands: one posits that consumers are per-

fectly rational, understand that incentives such as commissions may motivate agents to recommend

particular products, and therefore discount such advice. A second literature argues that consumers

are subject to behavioral biases, and may not be able to process all available information and make

informed conclusions.

Bolton et al. (2007) develops a model in which two intermediaries compete, each offering

two products, one suitable for one type of clients, the other for the other type of clients. While

intermediaries have an incentive to mis-sell, competition may eliminate misbehavior. Inderst and

Ottaviani (2010) show that even in a fully rational world, producers of financial products will pay

financial advisors commissions as a way to incentivize them to learn what products are actually

suitable for their heterogenous customers. Del Guerico and Reuter (2010) take a different tack,

arguing that sellers of mutual fund products in the US that charge high fees may provide intangible

financial services which investors value.

A second, more pessimistic, view, argues that consumers are irrational, and market equilibria

in which consumers make poorly informed decisions may persist, even in the face of competition.

Gabaix and Laibson (2005) develop a market equilibrium model in which myopic consumers sys-

tematically make bad decisions, and firms do not have an incentive to debias consumers. Carlin

(2009) explores how markets for financial products work in which being informed is an endogenous

decision. Firms have an incentive to increase the complexity of products, as it reduces the number

of informed consumers, increasing rents earned by firms. Inderst and Ottaviani (2011) present a

model with naive consumers, where naivete is defined as ignoring the negative incentive effects of

commissions, and find that naive consumers receive less suitable product recommendations.

The theoretical work is complemented by a small, but growing, empirical literature on the

role of competition and commissions in the market for consumer financial products. In a paper

that precedes this one, Mullainathan, Noth, and Schoar (2010) conduct an audit study in the

United States, examining the quality of financial advice provided by advisors. Woodward (2008)

demonstrates mortgage buyers in the U.S. make poor decisions while searching for mortgages. A

5

series of papers (e.g. Choi et al 2009, 2010) demonstrate that consumers fail to make mean-variance

efficient investment decisions, paying substantially more in fees for mutual funds, for example, than

they would if they consistently bought funds from the low-cost provider. In work perhaps most

closely related to this paper, Bergstresser et al. (2009) look at the role of mutual fund brokers in the

United States. They find that funds sold through brokers underperform those sold through other

distribution channels, even before accounting for substantially higher fees (both management fees

and entry/exit fees). Buyers who use brokers are slightly less educated, but by and large similar to

those who do not. They do not find that brokers reduce returns-chasing behavior.

In the next section we describe the basic economics of the life insurance industry in India,

discuss why whole insurance policies are dominated by term policies, and economic theories of why

individuals might still purchase whole policies. Section III discusses the theoretical framework that

guides our empirical tests. Section IV presents the experimental design, while Section V and VI

present our results. In section VII, we describe an equilibrium model of insurance markets in which

dominated products survive, even with competition. Section VIII concludes.

2 Term and Whole Life Insurance in India

Life insurance products may be complicated. In this section, we lay out key differences between

term and whole life insurance products, and demonstrate that the insurance offerings from the

largest insurance company in India violate the law of one price, as long as an individual has access

to a bank savings accounts. Rajagopalan (2010) conducts a similar calculation and also concludes

that purchasing term insurance and saving strictly dominates purchasing whole or endowment

insurance plans.

We start by comparing two product offerings from the Life Insurance Corporation of India

(LIC), the largest insurance seller in India. For many years, LIC was the government-run monopoly

provider of life insurance. We consider the LIC Whole Life Plan (Policy #2), and LIC Term Plan

(Policy #190), for a 25-year old male seeking at least Rs. 2,500,000 in coverage (approximately

USD $50,000), commencing coverage in 2010.

For a whole life policy, such a customer would make 55 annual payments (until the age of

80 is reached) of Rs. 55,116 (ca. $1,110 at 2010 exchange rates). The policy has a face value

6

of Rs. 2,500,000 if the client dies before age 80. In case the client survives until age 80, which

would be the year 2065, the product pays a maturation benefit equal to the coverage amount. The

coverage amount is not necessarily constant: it may be increased via LIC’s “bonus” policy, which

the insurance company may declare if it earns profits. For the past several years, bonuses have

ranged from 6.6% to 7% of the original coverage amount of the insurance policy. Unlike interest or

dividends, these bonus payments are not paid to the client directly. Rather the bonus is added to

the notional coverage amount, paid in case of death of the client, or, at maturity. The insurance

company does not make any express commitment as to whether, and how much, bonus it will offer

in the future.

A critical point to be made here is that the bonus is not compounded.

4

Rather, the bonus

added is simply the amount of initial coverage, multiplied by the bonus fraction. For example,

if the company declares a 7% bonus each year, the amount of coverage offered by the policy will

increase by .07*2,500,000=Rs. 175,000 each year. Thus, after 55 years, when the policy matures,

its face value will be Rs. 2,500,000 + 55*175,000=Rs. 12,125,000.

If these 7 percent bonuses were in fact compounded, the policy would have a face value of Rs.

2,500,000*1.07ˆ55, or over Rs. 103 million, an amount more than eight times larger. Stango and

Zinman (2009) describe evidence from psychology and observed consumer behavior that individuals

have difficulty understanding exponential growth. Consumers who do not understand compound

interest may not appreciate how much more expensive whole life policies are.

A second feature of the two policies may be their relative attractiveness to naive, loss-averse

consumers. Agents frequently dismissed term insurance as an option, arguing that the customer

was likely to live at least twenty years, hence the premiums would be “lost” or “wasted,” while

with whole life the purchaser was guaranteed to get at least the nominal premium paid returned.

In Appendix Table 1, we evaluate the whole life insurance product by creating a replicating

4

It is somewhat surprising that an insurance company has not entered this market and won a substantial amount

of business by offering a whole insurance product that does pay compounded bonuses. In fact, there are some whole

life products that pay a compounded bonus (i.e. the bonus rate is applied to both the sum assured amount plus all

previously accumulated bonus); thus, it is not the case that the insurance industry is unaware that consumers might

like these products. Rather, it seems that it is not possible for an insurance company to win substantial amounts

of business by aggressively selling whole products that pay compounded bonuses. One explanation for this may be

that competition really occurs along the margin of selling effort, as opposed to the quality of the product. In this

case, the products that have highest sales incentives will sell, and any particular insurance firm will have an incentive

to pay the highest commissions on the highest profit products. We present a formal model along these lines that is

consistent with our empirical results later in this paper.

7

portfolio, which consists of a term insurance policy plus savings in a bank fixed deposit account.

Each year, the replicating portfolio provides at least as much coverage (savings plus insurance

coverage) as the whole policy, while requiring the exact same stream of cash flows from the client.

A 25-year old man seeking coverage of Rs. 2,500,000 would pay Rs. 55,116 per year for whole

insurance. If instead he bought a 35-year term policy with Rs. 4,000,000 in coverage, he would

pay Rs. 11,996 each year for 35 years. Over that period, he could save the difference (55,116-

11,996=43,120); once the term policy expired, the replicating portfolio would save Rs. 55,116 per

year. In each year, the death benefit (of term payout, if the policy is active, plus savings) would be

greater than the benefit from the whole policy, including the bonuses. The differences are dramatic:

the initial coverage of the replicating portfolio is Rs. 4 million, vs Rs. 2.5 million for the whole

policy. At age 35, the term plus savings is worth 9% more than the whole payout. By age 55,

the replicating portfolio is worth 36% more than the whole payout, and by age 85 the replicating

portfolio would be worth Rs. 91 million, compared to Rs. 13 million benefit from the whole policy.

The replicating portfolio is almost seven times more valuable.

One argument commonly advanced in favor of whole life insurance is that it provides protec-

tion for the individual’s whole life, and thus eliminates the need to purchase new term insurance

plans in the future. If there is substantial risk that future term insurance premiums might increase

due to increases in the probability of death, then term insurance might be seen as more risky than

whole insurance. However, this argument does not affect our replication strategy, because the term

plus savings plan does not require the individual to purchase another term insurance policy 35

years later.

5

The individual has saved up enough in the savings account to provide self-insurance

after 25 years, which is greater than the amount of insurance that the whole life policy provides.

But even this comparison understates the difference in value dramatically, for at least two

reasons. First, the replicating portfolio builds up a substantial savings balance, which is liquid.

Second, if an individual does not pay each premium promptly, the insurance company has the

right to declare the policy lapsed. Some estimates suggests lapse rates are high: 6% of outstanding

policies lapse in a given year (Kumar, 2009). If the customer lapses after paying premiums for

three or more years, the plan guarantees a recovery value of only 30% of premiums paid (less the

5

Cochrane (1995) discusses this issue in the context of health insurance and proposes an insurance product that

also insures against the risk of future premium increases due to changes in risk.

8

first year’s premiums).

Thus, for an equivalent investment, the buyer receives up to six times as much benefit if she

purchase term plus savings, relative to whole. We are not aware of many violations of the law of

one price that are this dramatic. A benchmark might be the mutual fund industry: $1 invested in

a minimal fee S&P500 fund might earn 8% per annum, and therefore be worth $69 after 55 years.

If an investor invested $1 in a “high cost” mutual fund that charged 2% in fees, the value after 55

years would be $25, or about one third as large. The life insurance mark-up is thus by this metric

twice as large as the mark-up on the highest cost index funds.

2.1 Whole Life Insurance as a Commitment Device

One potential advantage of the whole life policy over term plus savings is that the whole life policy

contains committment features that some consumers value (Ashraf et al. (2006)). The structure

of whole life plans impose a large cost in the case where premium payments are lapsed, and thus

consumers that are sophisticated about their commitment problems may prefer saving in whole life

plans versus standard savings accounts where there are no costs imposed when savings are missed.

In particular, the LIC Whole Insurance Plan No. 2 discussed in the previous section returns nothing

if the policy “lapses’ within the first three years.

However, it is not clear that the commitment feature alone is sufficient to explain the pop-

ularity of whole life insurance. Ashraf et. al. (2006) finds only 25% of the population exhibit

hyperbolic preferences. Moreover, there are other savings products in the Indian context that offer

similar commitment device properties but substantially higher returns. Fixed deposit accounts

involve penalties for early withdrawal. Public provident fund accounts require a minimum of Rs.

500 per year contribution, and allow the saver no access to the money until at least 7 years after the

account is opened. If a saver does not contribute the 500 rupees in a particular year the account

is consider discontinued, and the saver has to pay a 50 rupee fine for each defaulting year plus the

500 rupees that were missed as installments.

Finally, there is no reason a financial services provider could not offer commitment savings

accounts without an insurance component. The fact that no such product has been developed in In-

dia or around the world suggests that this product is not simply satisfying demand for commitment

savings.

9

Nevertheless, we acknowledge that a desire to commit may be relevant for some consumers.

Hence, for any shopping visit in which we regard term insurance as the more appropriate product,

the mystery shopper clearly told the insurance agent that she or he was seeking risk coverage at a

low cost, rather than a savings vehicle.

3 Theoretical Framework

Our empirical work is motivated by recent theoretical work on the provision of advice to potential

customers. Our paper tests two types of predictions that arise from this class of models. The

first set of predictions concerns the quality of advice provided by commissions motivated agents.

These models predict that at least some consumers will receive low quality advice; i.e. they will

be encouraged to purchase an advanced product that has higher commissions but no real benefits

to them (Inderst and Ottaviani, 2011, Gabaix and Laibson, 2005).

6

We test this by measuring the

fraction of agents that recommend customers purchase whole insurance, even in the case where the

customer is only seeking insurance for risk protection (i.e. we shut down any commitment savings

channel).

The second set of predictions relates to how regulation and market structure affect the quality

of advice. We test three predictions from the theoretical literature.

Our first test centers on the role of competition in the provision of advice. Inderst and

Ottaviani (2011) and Bolton et. al. (2007) show that increased competition amongst agents who

provide products and advice can improve the quality of advice for customers. On the other hand,

Gabaix and Laibson (2006) show that increasing competition need not lead firms to unshroud

product characteristics that hurt naive consumers. Our auditors vary the level of competition

perceived by agents, by reporting whether their information about insurance comes from a friend

(low competition), or from another agent from which our auditor is thinking of purchasing insurance

(high competition).

Second, a large literature in economics predicts that competition between firms will induce

6

While the Gabaix and Laibson (2006) paper does not explicitly deal with commissions, it does show that firms

will not necessarily have the incentive to unshroud product attributes (such as commissions or low rates of return in

our case) because unshrouding these will not necessarily win the firm business. In our case, the analogy would be

that life insurance firms do not have the incentive to unshroud these attributes of whole insurance products because

they would lose a substantial proportion of business to banks and other financial service providers if individuals move

their savings out of life insurance.

10

firms to disclose all relevant information regarding products (Diamond (1985), Grossman (1989)).

In these models, mandatory disclosure enforced by the government does not change consumer

decisions and does not improve welfare. However, Inderst and Ottaviani (2011) argue that disclosure

requirements can improve the quality of advice by essentially converting unaware customers into

customers that are aware of how commissions can bias advice. We test how a disclosure requirement

on commissions impacts financial advice by studying a particular type of insurance product, a Unit

Linked Insurance Policy (ULIP), where agents were forced to disclose the commissions they earned

after July 1, 2010.

Lastly, a key feature of the recent theoretical models in Inderst and Ottaviani (2011) and

Gabaix and Laibson (2006) is the presence of two types of agents, with different levels of sophis-

tication. Inderst and Ottaviani (2011) predict that these sophisticated types will receive better

advice. We test this prediction by inducing variation in the level of sophistication demonstrated

by the agent during the sales visit.

4 Experimental Design

4.1 Setting

In this section we describe the basic experimental setup common to the three separate experiments

we ran in this study. All of the auditors used have at least a high school education. Intensive

introductory training on life insurance was provided by a former financial products sales manager,

and a principal investigator. Subsequently, each auditor was trained in the specific scripts they

were to follow when meeting with the agents. Each agent’s script was customized to match the

agents true life situation (number of children, place of residence, etc.). However, agents were

given uniform and consistent language to use when asking about insurance products, and seeking

recommendations. Auditors memorized the scripts, as they would be unable to use notes in their

meetings with the agents. Following each interview, auditors completed an exit interview form

immediately, which was entered and checked for consistency. The auditors and their manager were

told neither the purpose of the study, nor the specific hypotheses we sought to test.

Auditors were instructed not to lie during any of the sessions. Upon completion of the study,

all auditors were given a cash bonus which they used to purchase a life insurance policy from the

11

agent of their choice. All of our auditors chose to purchase term insurance.

In each experiment, treatments were randomly assigned to auditors, and auditors to agents.

Note that because the randomizations were done independently, this means that each auditor did

not necessarily do an equivalent number of treatment and control audits for any given variable of

interest (i.e. sophistication and/or competition). Table 1 presents the number of audits, number

of auditors, and number of life insurance agents for each separate treatment cell in each of our

three experiments. Since we were identifying agents as the experiment proceeded, we randomized

in daily batches. To ensure treatment fidelity, auditors were assigned to use only one particular

treatment script on a given day.

Life insurance agents were identified via a number of different sources, most of which were

websites with national listings of life insurance agents.

7

Contact procedures were identical across

the treatments. While some agents were visited more than once, care was taken to ensure no

auditor visited the same agent twice, and to space any repeat visit at least four weeks apart, both

to minimize the burden on the agents, and to reduce the chance the agent would learn of the study.

Table 2 presents summary statistics across the three experiments we report results on in

this paper. The Quality of Advice experiment was conducted in one major Indian city, and the

Disclosure and Sophistication experiments were conducted in second major Indian city.

8

Across

the experiments, between 50-75% of agents visited sold policies underwritten by the Life Insurance

Company of India (LIC), a state owned life insurance firm. This fraction is consistent with LIC’s

market share, which was 66 percent of total premiums collected in 2010.

In terms of the location of the interaction between the auditor and the life insurance agent, one

major difference between the Quality of Advice experiment and the Disclosure and Sophistication

experiments is that a substantial number of Quality of Advice audits occurred at venues outside

the agent’s office. These other locations were typically a restaurant, cafe, railway or bus station, or

public park. In the Disclosure and Sophistication experiments, the majority of audits took place

at the agent’s office. On average, each audit lasted about 35 minutes, suggesting these audits do

represent substantial interactions between our auditors and the life insurance agents. The length

7

We also included a small number of agents we found through outdoor advertisements and through a listing of

Life Insurance Corporation of India agents.

8

The Competition experiment was conducted as a sub-treatment within the Quality of Advice experiment, and

thus shares the same summary statistics.

12

of audit did not vary substantially across the different experiments.

Matched pair audit studies used to identify discrimination have been criticized on method-

ological grounds. These studies, which involve sending, for example, black and white car buyers to

purchase a car. Critics argue that even if auditors stick to identical scripts, they may exhibit other

differences (apparent education, income, etc.) that could lead sales agents to treat buyers differently

for reasons other than the buyer’s race or sex (Heckman, 1998). While our study is not subject

to this criticism–our treatments were randomized at the auditor level, so we can include auditor

fixed effects–we took great care to address other potential threats to internal validity. Outright

fraud from our auditors is very unlikely, as they were obliged to hand in business cards of the sales

agents. To monitor script compliance, we paid insurance agents within the principal investigators’

social network to “audit the auditors”–these agents reported that our auditors adhered to scripts.

The outcome we measure, policy recommended, is relatively straightforward, and auditors were

instructed to ask the agent for a specific recommendation. To prevent auditor demand effects, we

did not inform the auditors of the hypotheses we were interested in testing.

5 Quality of Advice

5.1 Quality of Advice: Catering to Beliefs Versus Needs

In this experiment we test the sensitivity of agents’ recommendations to the actual needs of con-

sumers, as well as to consumers potentially incorrect beliefs about which product is most appro-

priate for them. In particular, one reason agents may recommend whole insurance is a belief that

customers will value the commitment savings features. To examine this, we vary the expressed need

of the agent, by assigning them one of two treatments. In half of the audits, the auditor signals

a need for a whole insurance policy by stating: “I want to save and invest money for the future,

and I also want to make sure my wife and children will be taken care of if I die. I do not have

the discipline to save on my own.” Good advice under this treatment might plausibly constitute

the agent recommending whole insurance. In the other half of the audits, the auditor says “I am

worried that if I die early, my wife and kids will not be able to live comfortably or meet our financial

obligations. I want to cover that risk at an affordable cost.” In this case the auditor demonstrates

a real need for term insurance. By comparing agent recommendations across these two groups, we

13

can measure whether agent recommendation responds to agents true needs. Appendix Table A2

presents the exact wording of all of the experimental treatments in this study.

We also randomized the customer’s stated beliefs about which product was appropriate for

him or her. In audits where the auditor was to convey a belief that whole insurance was the correct

product for them, the auditor would state “I have heard from [source] that whole insurance may

be a good product for me. Maybe we should explore that further?” In the audits where the auditor

was to convey a belief that term insurance was the correct product for them, the auditor would

state ”I have heard from [source] that whole insurance may be a good product for me. Maybe we

should explore that further?”

Finally, to understand the role of competition, we also varied the source auditors mentioned

when talking about their beliefs. In the low competition treatment, the auditor named a friend as a

source of the advice. In the high competition treatment, the auditor said the suggestion had come

from another agent from whom the auditor was considering purchasing.

Each of these three treatments (product need, product belief, and source of information) was

assigned orthogonally, so this experiment includes eight treatment groups.

Table 3 presents a randomization check to see if there are important differences in the audits

that were randomized into different groups. The first two columns compare audits that were ran-

domized such that the auditor had either a bias for term (Column (1)) or a bias for whole (Column

(2)). As would be expected given the randomization, there are almost no systematic differences

across the two groups. The only significant difference is that audits assigned a bias towards whole

were approximately two percentage points more likely to be conducted at the auditor’s home. We

include audit location fixed effects in our specifications and find they do not substantially change

the results.

Columns (3) and (4) present characteristics of audits where the auditor was randomized into

having a need for term insurance (Column (3)) or a need for whole insurance (Column (4)). The

next two columns present the pre-treatment characteristics of audits where the source of the bias

was another agent (Column (5)) or a friend (Column (6)). There are also no statistically significant

differences in the pre-audit characteristics across these groups.

9

9

Throughout the paper, we use robust standard errors; results and significance levels are virtually identical if we

cluster standard errors at the level of randomization, auditor*day.

14

Before describing the experimental results, we emphasize how poor the quality of advice is: for

individuals for whom term is the most suitable product, only 5% of agents recommend purchasing

only term insurance, while 74% recommend purchasing only whole. A previous version of this paper

documented a range of wildly incorrect statements made by agents, such as “term insurance is not

for women;” “term insurance is for government employees only.” One even proposed a policy that

he described as term insurance, which was in fact whole insurance.

Table 4 presents our main results on how variation in the needs of customers and biases

of customers affect the quality of financial advice.

10

Column (1) presents results on whether the

agent’s final recommendation included a term insurance policy (in about 8% of the cases, agents

recommend the consumer purchase multiple products). We find that agents are 10 percentage

points more likely to make a final recommendation that includes a term insurance policy if the

auditor states that they have heard term insurance is a good product. We also find that agents are

12 percentage points more likely to make a recommendation that includes a term insurance policy

if the auditor says they are looking for low-cost risk coverage. Both of these results are statistically

significant at the 1 percent level. The interaction of these two variables is statistically insignificant.

This suggests that agents are just as likely to cater to beliefs as needs.

In column (2), we add auditor-fixed effects and controls for venue and whether the agent sells

policies underwritten by a government-owned insurer. The experimental results are unaffected.

Agents from the government owned insurance underwriters (primarily the Life Insurance Corpora-

tion of India) are 12 percentage points less likely to recommend a term insurance plan as a part of

their recommendation.

Column (3) presents the same exact specification as Column (1), however now the dependent

variable takes a value of one if the agent recommended only a term insurance plan. We find

much weaker results here. A customer stating that they have heard that term insurance is a good

product is only 2 percentage points more likely to receive a recommendation to only purchase term

insurance. We find that stating a need for affordable risk coverage only causes a 1.5 percentage

point increase in the probability that the agent will recommend exclusively term insurance. This

effect is not statistically significant at conventional levels. When the auditor both states that they

10

In this section we focus on the quality of advice given, and thus report results on how advice responds to a

customer’s needs versus beliefs. Later, we discuss the impact of the competition treatment when we focus on how

quality of advice might be improved.

15

need risk coverage and they have heard that term is a good product we find an increase of 5.3

percentage points, significant at the ten percent level. Column (4) adds controls.

Thus, comparing Columns (2) and (4) it appears that agents do respond to both the biases

and needs of customers, however, they primarily do it by recommending term insurance products

as an addition to whole insurance products, rather than recommending the purchase of term.

Overall, the results in Columns (1) - (4) suggest that agents will respond approximately

equally to both the needs and pre-existing biases of customers. These results are consistent with

the idea that agents maximize the expected revenue from an interaction, and the expected revenue

depends both on the probability that the customer will purchase as well as the amount of commission

that can be earned. Agents do not seem to attempt to de-bias customers who express perceived

needs inconsistent with actual needs; thus, in this context it seems unlikely that commissions

motivated agents are effective in undoing behavioral biases customers bring to their insurance

purchase decisions.

Columns (5) and (6) shows that stating an initial bias towards term insurance causes the

agent to recommend the customer purchase approximately 13 percent more risk coverage, while

expressing a need for risk coverage increases the recommended risk coverage by 17 percentage

points. Both of these effects are significant at the five percent level, but their interaction is not.

Again, these results suggest agents will cater approximately equally to the stated preferences of

a customer (even if those preferences are inconsistent with their actual needs), about as much as

they cater to the actual stated needs of customers.

Columns (7) and (8) test whether the recommended premium amounts are statistically differ-

ent across the treatments. We find that the bias and need treatments have small and statistically

insignificant effects on the level of premiums the agent recommends that customers pay to pur-

chase insurance. This suggests that although agents are recommending higher coverage levels for

those who either have a bias towards term or a need for term (Columns (5) and (6)), customers

are not paying higher premiums to obtain this additional coverage. Instead, the increase in risk

coverage observed in Columns (5) and (6) is due primarily to the fact that term insurance provides

dramatically more risk coverage per Rupee of premium.

Further evidence of this interpretation is obtained from the average amounts of risk coverage

and premium amounts when agents recommended term versus whole insurance (not reported). In

16

the case where the auditor sought risk coverage at an affordable cost and said they had heard risk

coverage was a good product for them, agents recommending term insurance proposed 2.3 million

rupees of risk coverage, with an annual premium cost of approximately 31,000 rupees. Agents

recommending whole insurance suggested customers purchase 522,000 rupees of risk coverage, with

an annual premium of approximately 28,000 rupees. Our auditors characteristics (income, depen-

dents) are the same no matter what beliefs they express, meaning there is no economic reason to

suggest greater coverage levels when the auditor expresses a preference for coverage at low cost.

One explanation for this result, consistent with the bad advice hypothesis, is that agents base their

recommendations on the amount of premiums customers can pay, as opposed to the amount of risk

coverage customers actual need. Our finding here is consistent with anecdotal evidence from dis-

cussions with our auditing team: agents typically start the life insurance conversation by estimating

how much the individual can afford to put into life insurance per month, rather than determining

how much risk coverage the customer needs.

In summary, we find the following. Despite the fact term is an objectively better policy,

between 60 and 80 percent of our visits end with a recommendation that the customer purchase

whole life insurance. Second, even when customers signal that they are most interested in term

insurance and need risk coverage, more than 60 percent of audits result in whole insurance being

recommended. Third, we find that agents primarily cater to customers (either their beliefs or needs)

by recommending that they purchase term insurance in addition to whole insurance, as opposed to

recommending term insurance alone. It is difficult to see how combining term and whole insurance

makes sense for someone who is seeking risk coverage.

6 Financial Advice and Market Structure

These previous results are consistent with the models of Inderst and Ottaviani (2011), Gabaix and

Laibson (2006) and Bolton et al. (2007) which suggest commissions motivated sales agents will have

an incentive to recommend more complicated, but potentially unsuitable, products to customers

who are not wary of the agency problems that commissions create (at least under some market

structures). In this section we turn to testing theoretical predictions on how advice responds to the

regulatory and market structure. As our experimental design allows us to measure the type of advice

17

given, we focus on three predictions. First, the threat of increased competition from another agent

will reduce the probability an unsuitable product is recommended. Second, increasing consumers

awareness of commissions will reduce the tendency to recommend unsuitable products. Third,

agents will provide different advice to sophisticated versus unsophisticated consumers.

6.1 Competition

One way agents may compete with each other is to offer better financial advice. Standard models

of information provision suggest that competition amongst advice providers will lead to the op-

timal advice being given; customers will avoid salesmen who give low quality advice and thus in

equilibrium only high quality advice will be given.

In any given interaction between an agent and a customer, it is likely that the agent perceives

he has some market power, in that the customer would have to pay additional search costs to

purchase from another agent. In this treatment we attempted to experimentally reduce the agent’s

perceived amount of market power by varying whether the customer mentions that they have

already spoken to another agent. Audits randomized into the high competition treatment stated

that they heard from another agent term (or whole) might be a good product for them. Audits

randomized into the low competition treatment state that they heard from a friend that term (or

whole) might be a good product for them.

The audits for which these data are based on are the same as those used in the Quality of

Advice experiment. Table 5 presents our results on the impact of greater perceived competition

on the quality of advice provided by life insurance agents. The specifications reported here are the

same as those in Table 4, but we now introduce a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the

auditor’s bias came from a competing agent, and zero if the bias came from a friend. Columns

(1) and (2) show that overall the induced competition does not seem to have an important effect

on whether agents recommend term insurance as part of their package recommendation. Columns

(5) and (6) show that the competition treatment also did not have an overall increasing effect on

whether only a term policy was recommended.

Columns (3) and (4) introduce a set of interaction terms between the bias treatment, the

need treatment, and the competition treatment. We are particularly interested in the treatment

where the customer is biased towards whole insurance but demonstrates a need for term insurance.

18

In this setting the agent has the potential to “de-bias” the auditor as their beliefs are inconsistent

with their insurance needs. In Columns (3) and (4) we find that the agent is substantially more

likely to debias agents when the threat of competition looms. This effect is measured by summing

the coefficients on the variables Competition and (Need=Term)*Competition. The sum suggests

agents advising customers who need term but are biased towards whole are 10 percent more likely

to recommend term insurance if they perceive higher levels of competition. The hypothesis that

(Need=Term)*Competition + Competition = 0 can be rejected at the 5% level. This result suggests

that if perceived competition is high enough, agents will attempt de-bias customers as a way of

winning business.

We do not, however, find that competition increases the possibility that agents will de-bias

customers who have a belief that term insurance is a good product but need help with savings.

We find that the coefficient on the interaction (Bias=Term)*Competition is small and statistically

insignificant.

Columns (7) and (8) report the same specification as those in Columns (3) and (4), however

the dependent variable takes the value of one if the agent recommended the customer purchase

only term insurance. We do not find any evidence that agents attempt to de-bias consumers

by recommending they only purchase term insurance. The coefficient on the interaction term

(Need=Term)*Competition is small and insignificant in Columns (7) and (8). We find that the

competition treatment is only effective, in this case, when the agent has both a bias and a need

towards term insurance. One interpretation of this result is that agents assume that a customer

who has the knowledge to know that term insurance is the best product for someone who needs

risk coverage is almost surely going to purchase term insurance from the other agent. Thus, the

agent in the audit chooses to compete by recommending only a term insurance purchase as well.

6.2 Disclosure

On July 1, 2010, the Indian Insurance Regulator mandated that insurance agents must disclose

the commissions they would earn when selling a specific type of whole insurance product called a

ULIP. ULIPs are very similar to whole insurance policies, except the savings component is invested

in equity instruments with uncertain returns. This regulation was enacted as the Indian insurance

regulator faced criticism from the Indian stock market regulator that ULIPs should be regulated

19

in the same was as other equity based investment products. The insurance regulator responded to

these criticisms by requiring agents to disclose commissions when selling ULIPs.

There are two specific features of this policy we emphasize before discussing our empirical

results. First, it is important to note that the disclosure of commissions required on July 1st is

in addition to a disclosure requirement on total charges that came into effect earlier in 2010. In

other words, prior to July 1, agents were required to disclose the total charges (i.e. the total costs,

including commissions) of the policies they sell, but they were not required to disclose how much

of those charges went to commissions versus how much went to the life insurance company. Thus,

the new legislation requiring the specific disclosure of commissions gives the potential life insurance

customer more information on the agency problem between himself and the agent, but does not

change the amount of information on total costs. This allows us to interpret our results as the effect

of better information about agency, rather than better information about costs more generally.

To focus the visits on ULIPs, agents began by inquiring specifically about ULIP products

available. The experimental design here involves two components. First, we conducted audits before

and after this legal change to test whether the behavior of agents would change due to the fact that

they were forced to disclose commissions. Second, we also randomly assigned each of these audits

into two groups, where in one group the auditor conveys knowledge of commissions and in the other

group the auditor does not mention commissions. We created these two treatments as we believed

only customers who have some awareness of these commissions were likely to be affected by this law

change. In one group, we had the auditor explicitly mention that they were knowledgeable about

commissions by stating: “Can you give me more information about the commission charges I’ll be

paying?” In the control group, the auditor did not ask this question about commission charges.

Table 6 presents summary statistics on the disclosure experiment audits. Column (1) pertains

to the full sample audits, while (2) and (3) present summary statistics on the audits before and

after the regulation went into effect. There are several differences between the pre- and post-

audits. In particular, post disclosure change audits were more likely to be conducted with the Life

Insurance Company of India, and the meetings took place in different venues. These differences

suggest that caution is warranted when comparing the pre- and post- results. Columns (7) and

(8) of Table 3 present summary statistics on the randomization of the different levels of knowledge

about commissions.

20

6.3 Did the Disclosure Requirement Change Products Recommended?

We first examine whether audits conducted after the disclosure requirements went into effect were

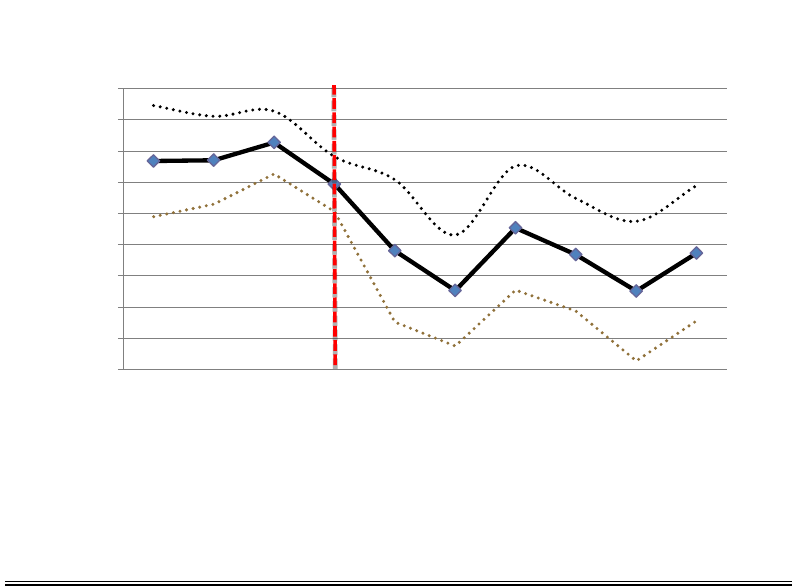

less likely to result in the agent recommending a ULIP policy. Figure 1 shows the weekly average

fraction of audits that resulted in a ULIP recommendation. Prior to the commissions disclosure

reform, agents recommended ULIPs eighty to ninety percent of the time. Following the reform,

there is an immediate and discrete drop in the fraction recommending ULIPs, to between forty and

sixty-five percent of audits. The discrete jump suggests the observed differences are driven by the

disclosure requirement, rather than being attributable to a steady downtrend trend in the fraction

of agents recommending ULIP policies over time.

Table 7 presents the formal empirical results. The dependent variable in all specifications

in this table takes a value of one if the agent recommended a ULIP product and zero otherwise.

The independent variable Post Disclosure indicates whether or not the audit occurred after the

legislation went into effect, July 1st (our earliest post-disclosure audits occurred on July 2nd). The

variable Disclosure Knowledge equals one where the client expresses awareness that agents receive

commissions and zero otherwise. Finally, we control for whether the agent is from a government

underwriter, auditor fixed effects, and the location of the audit.

Column (1) presents a regression without controls. We find that in the post period a ULIP

product was 25 percentage points less likely to be recommended. This finding is consistent with

the prediction that agents treat customers who are concerned about commissions differently than

those who are not, and that disclosure policy can improve customer awareness. We do not find

the randomized treatment of the auditor demonstrating knowledge of the commissions significant

(Disclosure Knowledge), nor do we find the interaction to be significant.

One potential threat to the validity of our analysis is the change in composition of agents

between the pre- and post-period. Perhaps most important is the difference between the fraction

of agents selling policies issued by government-owned insurance companies before and after the law

change. In Column (2), we control for whether the agent works for a government-run insurance

company, as well as location and auditor fixed-effects. The point estimate is slightly smaller, but

the effect is still quite sizeable at 19 percentage points.

In columns (3) and (4) we examine agents for government-owned and private insurance com-

21

panies seperately. Among those selling policies underwritten by government-owned companies,

there is a 30 percent decrease in the likelihood of recommending a ULIP policy after the disclosure

law becomes effective. Amongst private underwriters, we find a negative point estimate, although

the coefficient is not significant at standard levels. The result in Column (3) suggests that the

observed reduction in ULIP recommendations in the whole sample is not driven by a compositional

shift in the types of agents the auditors meet.

In terms of magnitudes, given the overall percentage of ULIP recommendations in this sample

was 71 percent, the approximately 20 percent decrease in ULIP recommendations once disclosure

commission became mandatory is an economically large effect. Further analysis (not reported)

finds agents were approximately 20 percentage points more likely to recommend whole insurance

type products following the law change. There was no change in their propensity to recommend

term insurance. Thus, it appears that the ULIP disclosure law change primarily led to substitution

away from high commission ULIP products to high commission whole insurance products.

Turning to the experimental treatment, we do not find that audits where our agents showed

knowledge of the new disclosure requirements are associated with lower levels of ULIP recommenda-

tions. The coefficient on the Disclosure Knowledge variable is small and statistically insignificant in

all of the specifications. This treatment does not seem to be affected by the disclosure requirement.

Columns (5) and (6) test whether the commission disclosure requirement had important

impacts on the amount of risk coverage and premium payments recommend by agents. We find no

statistically significant differences here, suggesting that the types of products recommended were

similar in terms of their risk characteristics after the policy change.

6.4 Customer Sophistication

In our final experiment, we manipulated the the level of sophistication about life insurance policies

projected by the auditor. Each auditor was randomly assigned to portray either high or low levels

of sophistication.

Sophisticated auditors say:

“In the past, I have spent time shopping for the policies, and am perhaps surprisingly some-

what familiar with the different types of policies: ULIPs, term, whole life insurance. However, I

am less familiar with the specific policies that your firm offers, so I was hoping you can walk me

22

through them and recommend a policy specific for my situation.”

Unsophisticated agents, on the other hand, state:

“I am aware of the complexities of Life Insurance Products and I don’t understand them very

much; however I am interested in purchasing a policy. Would you help me with this?”

To ensure clarity of interpretation of the suitability of recommendations, we built into the au-

ditors script several statements that suggest a term policy is a better fit for the client. Specifically,

the auditor expressed a desire to maximize risk coverage, and stated that they did not want to use

life insurance as an investment vehicle.

We predict that individuals that are sophisticated about life insurance products will be more

likely to receive truthful information from life insurance agents; agents internalize that sophisticated

agents are not swayed by false claims, and thus presenting dishonest information to sophisticated

agents is wasted persuasive effort. In the specific context of our audits this prediction suggests that

life insurance agents should be more likely to recommend the term policy to sophisticated agents.

Note that we designed our scripts so sophistication here only means that the potential customer is

knowledgeable about life insurance products; both sophisticated and unsophisticated agents state

that they have the same objective needs in terms of life insurance.

Table 3 presents a randomization check for the Sophistication experiment. The only statis-

tically significant different between the sophisticated and non-sophisticated treatments is that the

sophisticated treatments were about eight percentage points less likely to occur at other venues.

Overall, the randomization in this experiment appears to be successful. We control for audit loca-

tion in our results and find this has little impact on the effect of sophistication on recommendations.

The results from the sophistication experiment, reported in Table 8, provide some evidence in

support of our prediction that sophisticated customers will receive better advice. We use the same

specification as in the previous experiments to analyze this data. In Column (1) the dependent

variable takes a value of one if the agent’s recommendation included a term insurance plan, and

zero otherwise. We find that the sophisticated treatment causes a ten percentage point increase

in the likelihood that an agent includes term insurance as a part of their recommendation. This

23

result is statistically significant at the 10 percent confidence level. In Column (2) we include a

set of control variables, the point estimate and confidence interval are virtually unchanged. Thus,

we do see that agents make some attempt to cater to sophisticated individuals by offering term

insurance.

However, in Columns (3) and (4), where the dependent variable takes a value of one if

the agent recommended the auditor purchase only a term a insurance plan, we find there is no

statistically significant effect of sophistication. Similar to the results in the bias versus needs

experiment, it appears that agents attempt to cater to more sophisticated types by including term

as a part of a recommendation. However, they do not switch to recommending only term insurance,

even to customers who signal sophistication.

In Columns (5) and (6) we look at the impact of sophistication on the amount of coverage

recommended by the life insurance agent. Without controls, we find that sophisticated agents

receive guidance to purchase approximately 22 percent more insurance coverage (Column (5)). In

Columns (7) and (8) we test whether sophisticated agents receive different recommendations in

terms of how much premiums they should pay for insurance. We find that signaling sophistication

does not have an important impact on the amount of premiums that agents recommend paying,

although the confidence interval admits economically meaningful effects of up to 25 percent lower

premium costs. Combining the results in Columns (5) - (8), we see that, similar to our results on

coverages and premiums in the other experiments, agents seem to recommend approximately the

same amount of premiums be paid, regardless of our intervention; they cater to customers primarily

by adding a relatively inexpensive term product on top of whole insurance to increase risk coverage

without substantially changing premium payments.

7 A Model of Commissions, Bad Advice, and Dominated Prod-

ucts

We, and others, have argued that whole life insurance is dominated by term insurance for individ-

uals who seek insurance mainly for risk coverage. While the goal of this paper is to understand

commissions motivated agent behavior (rather than offer a competitive analysis of the Indian in-

surance industry), it does raise a puzzle: why do the more expensive, dominated, products, such as

24

whole insurance, persist in a setting with competition? We consider here how a dominated product

could survive, even in a competitive equilibrium.

We present a simple model, inspired by Gabaix and Laibson (2006), which provides one

explanation for how a dominated financial product might exist in competitive equilibrium. The

model takes the empirical results found in this paper, that commissions motivated agents appear

to provide poor financial advice, and shows how it is possible that if at least some consumers are

persuaded by bad advice then it is possible that a dominated product like whole insurance could

persist. The model may be particularly relevant for a country like India with a large number of

new insurance customers entering the market who are still learning about these products and may

be less sensitive to important differences in the long run returns available.

In the model, we focus primarily on the risk coverage offered by the insurance products. The

price of term insurance is the premium, while the “price” of whole insurance should be thought of as

the premium cost minus any savings value that exists beyond the risk coverage. This is equivalent

to assuming whole insurance can be replicated by purchasing term insurance and investing in a

savings account. Thus, the model is set up such that buyers should choose whole insurance only if

the price is cheaper than term insurance. However, we show that an equilibrium is possible where

whole insurance has a higher price than term insurance.

The model has two types of consumers. Sophisticated consumers understand that whole and

term insurance are the same product (and thus would always choose the cheaper one), know their

own optimal amount of insurance, given prices, and are immune to the persuasive efforts of agents.

There is a fixed, exogenous number of sophisticated consumers, s, who want to purchase term

insurance, and each has a demand function for term insurance equal to α − p

t

, where p

t

is the

price of term insurance.

Unsophisticated consumers, in contrast, can be persuaded to purchase a dominated product

if there is an agent that exerts enough effort. In particular, we assume unsophisticated agents

demand an amount of insurance α − p

w

once they have met with a commissions motivated agent.

Agents must exert effort to identify and sell to unsophisticated consumers. We assume that the

number of customers they find is equal to the commission on selling insurance set by the insurance

company, c. Intuitively, the higher that the insurance firm sets commissions, the more incentive

agents have to approach customers and sell insurance. In addition to commissions payments, the

25

insurance firm incurs an underwriting cost of k per unit of either term insurance or whole insurance

sold.

The game play is as follows. In period 0, the firm(s) choose whether to offer term, whole,

or both insurance products. They also choose the prices p

w

and p

t

and the commissions they will

pay agents to sell whole and term insurance (c

w

, c

t

). In the second period, agents respond to the

incentives set by the insurance companies, and consumers make decisions on how much whole and

term insurance to purchase and insurance. An Appendix contains the proofs of all the results

discussed here.

7.1 Monopolist Insurance Company

A monopolist insurance firm has three possible options (1) offer only term insurance (2) offer whole

and term insurance (3) offer only whole insurance. In the Appendix we show that the monopolist

insurance firm will choose to offer both term and whole insurance. The monopolist firm will pay

zero commissions for the sale of term insurance (as paying commissions on term insurance does not

increase demand) and will charge a price of

α+k

2

for term insurance. The monopolist firm will pay

positive commissions for the sale of whole insurance because demand is increasing in commissions.

The firm will set the whole insurance price (p

w

) equal to

1

3

(2α + k) and will pay commissions

1

3

(α − k). Note that as long as α > k (a condition necessary for there to be positive demand for

insurance), that the price of whole insurance will be higher than the price of term insurance.

The intuition for this solution is that offering both term and whole insurance offers the

monopolist firm a way to set different commissions and prices for sophisticated versus unsophisti-

cated customers. Sophisticated consumers cannot be persuaded by commissions motivated agents,

and thus the firm chooses to set commissions to zero and charge lower prices for term insurance.

However, unsophisticated consumers can be persuaded to purchase whole insurance. Thus, the

insurance firm chooses to pay higher commissions to encourage agents to persuade consumers to

purchase insurance, and then passes these higher commissions onto the consumer in terms of higher

prices.

26

7.2 Two Competing Insurance Companies

We now analyze the impact of competition by considering a Bertrand pricing game where two firms

compete by setting term and whole commissions and prices. This game has two players, firm i and

firm j. A strategy in this game consists of (1) a choice of which products to offer (term, whole, or

both) (2) prices and commissions for each product offered. A firm’s payoff function is the profit it

earns given its choice of what products, prices, and commissions to offer as well as the other firm’s

choices.

The payoffs are defined as follows. For term insurance, we use the usual Bertrand pricing game

(with homogenous products) assumption that firm i obtains the full market of all s sophisticated

consumers if p

i

< p

j

(and vice versa). For whole insurance, consumers can be influenced to purchase

both by higher commissions and lower prices. The number of unsophisticated consumers that firm i

sells to given it pays commissions c

i

is c

i

− bc

j

. The parameter b, which we assume is always greater

than zero, measures the degree to which firm i and j’s insurance products compete with each other

for customers. If b equals zero then the fact that firm j is paying high commissions does not change

the demand for firm i’s insurance. If b is large, however, then an increase in commissions by firm

j causes a fraction of consumers to switch from firm i’s insurance product to firm j’s product.

Note, however, that once unsophisticated consumers have been persuaded to purchase from a

particular firm because of commissions, the insurance company can charge them the monopoly price.

In this sense, competition for unsophisticated consumers happens primarily through commissions,

and not through prices. The intuition is that unsophisticated consumers respond strongly to the

persuasiveness and effort of agents in choosing what product to buy, but less strongly to the level

of prices.

Bertrand competition over prices in the market for term insurance leads to both firms pricing

term insurance at marginal cost k. In the Appendix we show that the Nash equilibrium commissions

on whole insurance are c

∗

i

= c

∗

j

=

α−k

3−2b

, and the Nash equilibrium prices are p

∗

i

= p

∗

j

=

(2−b)α+(1−b)k

3−2b

.

Note that for commissions and prices to be positive we need b ≤

3

2

.

Even though term and whole insurance are the same product in this model, an equilibrium

exists where whole insurance has a higher price than term insurance, and where competition be-

tween firms will not eliminate this dominated product. Analogous to the result in Gabaix and

27

Laibson (2006), a strategy of un-shrouding the whole policy does not work because selling the dom-

inating term policy does not offer the margins necessary to pay large commissions. Thus, it is not

profitable for firms to educate consumers on the fact that whole insurance is simply an expensive

version of term insurance. In equilibrium, firms sell low commission term insurance to sophisticated

consumers, and high commission whole insurance to unsophisticated consumers.

The model also has an interesting prediction on the impact of competition in this market.

When paying commissions causes the competitor to lose more business (b increases), competition

amongst firms leads to an increase in commissions and prices.

11

Thus, when insurance firms

attract customers mainly through commissions, competition can actually lead to higher prices (and

commissions), relative to a monopoly provider. The intuition for this result is that as a monopoly

provider, paying higher commissions loses more in profits due to higher costs than it gains in extra

business. However, when firms compete over commissions, then it becomes necessary to pay higher

commissions to win business, and profits for each sale are lower because more commissions have to

be paid.

We believe this model is a plausible explanation for why a dominated product like whole

insurance can persist in this market. The model fits the basic empirical facts observed in this

market: 1) Term insurance and whole insurance co-exist, although whole insurance can be repli-

cated by term insurance and savings accounts 2) Commissions on whole insurance are substantially

higher than term insurance 3) Agents provide poor advice (i.e do not try to de-bias consumers to-

wards whole insurance) 4) The industry has multiple, seemingly competitive, insurance providers.

Nonetheless, further empirical work is necessary to distinguish the model presented from other po-

tential explanations for the existence of dominated products, such as entry barriers or other market

frictions.

12

8 Conclusion

A critical question facing emerging markets with large swaths of the population entering the formal

financial system is how these new clients will receive good information on how to make financial

11

See appendix for the proof that prices increase.

12

It is important to note that the Indian insurance industry is characterized by significant barriers to entry, including

licensing restrictions and capital requirements, as well as scale economies.

28

decisions. Clearly, the private sector will be important in educating new investors and providing