EQUAL CHANCE FOR ALL

AN EQUAL SAY AND AN

The Challenge of Credit

Card Debt for the African

American Middle Class

by: Catherine Ruetschlin, Dēmos

Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, NAACP

December 2013

n a a c p

Roslyn M. Brock,

Chairman, National Board of Directors

Lorraine Miller,

Interim President and CEO

a c k n o w l e d g e m e n t s

e NAACP Economic Department thanks Dēmos for their research,

design, analysis, and development of this report. We particularly

thank Catherine Ruetschlin for her contributions to this report.

e NAACP Economic Department acknowledges the leadership of

the National Board of Directors Economic Development Committee

chaired by Leonard James, III and the Housing Committee chaired

by Attorney Gary Bledsoe.

Catherine Ruetschlin would like to thank Amy Traub for her expert

insights and editorial assistance.

a b o u t t h e n a a c p

e mission of the National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People is to ensure the political, educational, social, and

economic equality of rights of all persons and to eliminate race-

based discrimination.

a b o u t d ē m o s

Dēmos is a public policy organization working for an America where

we all have an equal say in our democracy and an equal chance in

our economy.

d ē m o s m e a n s “t h e p e o p l e .”

It is the root word of democracy, and it reminds us that in America,

the true source of our greatness is the diversity of our people. Our

nation’s highest challenge is to create a democracy that truly empow-

ers people of all backgrounds, so that we all have a say in setting the

policies that shape opportunity and provide for our common future.

To help America meet that challenge, Dēmos is working to reduce

both political and economic inequality, deploying original research,

advocacy, litigation, and strategic communications to create the

America the people deserve.

Table of Contents

1. Key Facts

2. Introduction

3. The CARD Act provides new protections

for African American borrowers

4. The credit card debt basics of African Americans: balance, APR,

and getting by on debt

5. Credit cards fill-in when a public safety net or private assets

are not available, leading households to turn to credit card

debt to finance human capital and other investments

6. African Americans report having worse credit scores

7. African Americans are more likely to be called by bill collectors

and to have seen credit tighten

8. Policy recommendations

1 • THE CHALLENGE OF CREDIT CARD DEBT FOR THE AFRICAN AMERICAN MIDDLE CLASS

Key Facts

I

n the wake of the worst eects of the Great Recession, African Americans, like

Americans as a whole, are getting their balance sheets in order and paying

down credit card debt. But new research from Dēmos’ National Survey on

Credit Card Debt of Low- and Middle-Income Households nds that African

Americans face challenges to their nancial security that are unlike those of white

households. In early 2012 Dēmos surveyed a nationally representative sample of

moderate-income households carrying credit card debt for at least three months;

this paper is part of a series of reports presenting our ndings. e results reveal

that, for many people, credit cards become a “plastic safety net” to replace dwin-

dling incomes, private assets, and social investments, and to help families stretch

their resources when paychecks and savings are not enough. We nd that under

dicult economic conditions many African American families rely on credit

cards to make ends meet or invest in their future—despite paying high interest

rates and suering more negative consequences of debt than other groups.

Among moderate-income households carrying credit card debt:

e African American middle class is paying down debt but still relies on

credit cards to make ends meet.

• African Americans carrying credit card debt owe less than they did in

2008, carrying an average balance of $5,784 today compared to $6,671

in our 2008 survey.

• Similar to white and Latino Americans, 42 percent of African

Americans report using their credit cards for basic living expenses like

rent, mortgage payments, groceries, utilities, or insurance because they

do not have enough money in their checking or savings accounts.

e African American middle class—like the American middle class as a

whole—uses credit cards to make critical investments in their future, includ-

ing for higher education, entrepreneurship, and medical expenses.

• Fiy percent of indebted African American households who incurred

expenses related to sending a child to college report that it contributed

to their current credit card debt.

• Nearly all of the African Americans in our survey who incurred expenses

from starting a new business charged those expenses to a credit card

and have not been able to pay it o: 99 percent of African American

December 2013 • 2

households still carry that expense on their credit card bill compared to

80 percent of whites.

• Forty-three percent of African Americans—similar to whites and

Latinos—reported that out of pocket medical expenses contribute to

their credit card debt.

e African American middle class reports worse credit scores and dierent

causes of poor credit.

• When asked to identify their credit score within a range, just 66% of

African American households report having a credit score of 620 or

above, compared to 85 percent of white households.

• When asked to describe their credit score, only 42 percent of African

American households reported having “good” or “excellent” credit,

compared to 74 percent of white households.

• Among households reporting poor credit, African American households

were more likely to report that late student loan payments or errors

on their credit report contributed to their poor credit scores. White

households were more likely to report that late mortgage payments and

the use of nearly all existing lines of credit contributed to their poor

credit scores.

Moderate-income African Americans have similar rates of default and late

payments to moderate-income white Americans.

• ere were no signicant dierences in the frequency of African

American and white households declaring bankruptcy, being evicted,

or having property repossessed.

• ere were no signicant dierences in the number of times African

Americans and whites were late on credit card payments.

African Americans are more likely to be called by bill collectors, and to have

seen credit tighten.

• Seventy-one percent of African American middle-income households

had been called by bill collectors as a result of their debt, compared to

50 percent of white middle-income households.

• Just over half of African American middle-income households reported

having a credit card cancelled, seeing their credit limit reduced, or being

denied for a credit card in the three years following the recession.

3 • THE CHALLENGE OF CREDIT CARD DEBT FOR THE AFRICAN AMERICAN MIDDLE CLASS

Introduction

M

illions of Americans are still struggling with unemployment, lower

incomes, and the loss of wealth as a consequence of the Great Reces-

sion. But the fallout of the nancial crisis and the burst of the hous-

ing bubble hit people of color especially hard, exposing the relative

vulnerability that persisted among African Americans in the years since the Civil

Rights Movement. Over the 5 years since the nancial crisis African Americans

experienced the greatest economic losses of any group in the country, includ-

ing the highest unemployment rates and the biggest drops in annual income.

In tough economic times like these, many families have to nd a way to sup-

plement their earnings just to maintain a decent standard of living. When the car

breaks down or the furnace leaks, households straining to meet a tight budget

may drain their savings accounts or borrow to make ends meet. But African

Americans have fewer assets to fall back on than other households, owning just

$1 in wealth for every $20 owned by whites. And unlike white households, more

than half of that wealth is held in housing, making it less accessible in times of

emergency. Home equity was also subject to the massive devaluation associated

with the housing bubble’s collapse, resulting in a disproportionate loss of wealth

among African Americans when the bubble burst. In this report, we look at how

moderate-income African Americans are using credit cards in the aermath

of the Great Recession. We nd that under dicult economic conditions, mil-

lions of African American families rely on credit cards to make ends meet – de-

spite paying high interest rates and suering more negative consequences of debt

than other groups.

Credit cards gained importance for household nances over the past generation

as incomes stagnated and many families saw their buying power decline. In the

30 years from 1980 to 2010, while the size of the US economy more than doubled,

the median American household saw income rise by just 10 percent. Even in this

post-Civil Rights era, the advance of racial economic equity was similarly stag-

nant. African American families saw almost no gains in income relative to whites

over the period, barely climbing from earnings at 58 percent of white family in-

comes in 1980, to 61 percent in 2010. At the same time, the wealth divide actually

worsened: according to the Institute for Assets and Social Policy, between 1984

and 2009 the racial wealth gap nearly tripled.

Over the same period, employment security began to wither as new trade rules

increased competition for jobs and employers decreasingly oered benets like

health insurance and traditional pension coverage that used to be an essential part

of hiring agreements. Oshoring in particular proved a severe blow to the African

American middle class, who were disproportionately employed in manufactur-

December 2013 • 4

ing. e debilitation of organized labor, beginning with the policies of Ronald

Reagan, further diminished the number of good jobs available to African Amer-

ican workers. From 1980 to 2010, unemployment for African Americans consis-

tently hovered around twice that of white workers.

In the years since 1980, as economic security for the middle class began to

disappear, the social safety net became increasingly inadequate to cover the new

burdens placed on household budgets. For many people, credit cards became

a “plastic safety net” to replace dwindling income growth, private assets, and

social investments, and to help families stretch their resources when paychecks

and savings were not enough.

e Great Recession intensied both the need for social protections and their

paucity as unemployment soared, incomes declined, and poverty hit record levels.

Critical programs designed to cover workers when the economy fails could not

compensate for the gap le by decades of policies weakening the middle class.

Unemployment insurance, for example, provided coverage for just 24 percent

of unemployed African Americans and 33 percent of unemployed whites in

2010. e average insurance payment in 2010, 2011, and 2012 was just $300

per week. Our survey found that in many cases, the hardship of unemployment

pushed families to take on debt just to get by.

In early 2012, Dēmos conducted a nationally representative survey of Amer-

icans carrying credit card debt in order to better understand what the trends in

borrowing mean for moderate-income households and for people of color today.

e 2012 National Survey on Credit Card Debt of Low- and Middle-Income House-

holds follows two previous Dēmos surveys, conducted in 2005 and 2008. Our re-

sults show that African American households have paid down their credit card

balances since the beginning of the recession, yet still experience nancial pres-

sures that compel them to put critical expenses – like medical bills or the cost

of education – on their credit cards. At the same time, these households were

signicantly more likely than other groups to see their credit tighten following

the nancial crisis. And the consequences of carrying debt fell harder on African

Americans, too; our study reveals that African Americans are far more likely to

be called by bill collectors than white households, and far less likely to report

a good credit score.

e National Survey on Credit Card Debt of Low- and Middle-Income House-

holds is a nationally representative survey of 997 currently indebted households

who have carried a balance on their credit card for at least three months. is

paper is part of a series of reports presenting our ndings from the survey. Afri-

can Americans make up 15 percent of the sample, yielding a margin of error of

11.3 percentage points.

We identied low- and middle-income households based on their relationship

to the county-level median income for each respondent, with those earning be-

tween 50 and 120 percent of the local median included in the survey. e median

5 • THE CHALLENGE OF CREDIT CARD DEBT FOR THE AFRICAN AMERICAN MIDDLE CLASS

income for African American households included in the indebted sample was

$51,450—that is about 2 percent higher than the median household income of

$50,045 for the US population overall in 2011. Relative to the total US population,

the typical African American family in our survey is squarely middle class. In

all, eighty percent of the African American households surveyed earned between

$20,000 and $100,000 per year, placing them within the middle three quintiles of

income distribution for 2011. But due to a signicant wage gap, high unemploy-

ment, and institutional barriers in the labor market, African Americans in gen-

eral face the lowest incomes of all racial and ethnic groups in the country, with a

median income of just $32,229, or less than two-thirds of the median for the total

population. e majority of African Americans in our sample are high earners

relative to the African American population as a whole.

According to the most recent Federal Reserve data, 79 percent of African

American households with a credit card carry credit card debt. With a typical

credit card debt burden of $5,784, the average African American household in our

survey owes credit card companies as much as 13 percent of their annual income.

is study tells their stories, examining the reasons why African Americans turn

to credit cards and the repercussions for their household nances.

Methodology

In February and March of 2012, Dēmos and GfK Knowledge Networks con-

ducted a survey of 1,997 households, including 997 households who had carried

credit card debt for more than three months and 1,000 households who had credit

cards but no credit card debt at the time of the survey. For our survey, moder-

ate-income is dened as a total household income between 50 percent and 120

percent of the local (county-level) median income. All of our respondents were at

least 18 years of age. In order to ensure that the indebted sample captures house-

holds who carry credit card debt, as opposed to those carrying a temporary bal-

ance, we only included households who reported having a balance for more than

three months. e margin of error for the total indebted sample is +/- 3.9 percent-

age points.

An additional sample was used to obtain reliable base sizes for African Amer-

ican and Latino populations. e margin of error for the oversample of 152 Afri-

can American households is +/- 11.3 percentage points. e margin of error for

the oversample of 205 Latino households is +/-9.1 percentage points.

December 2013 • 6

The CARD Act Provides

New Protections for African

American Borrowers

I

n 2008, the US Congress passed the Credit CARD Act, providing security for

consumers by requiring that credit card companies comply with fair and trans-

parent practices for billing and fees. e provisions of the CARD Act require

that monthly credit card statements include key information about debts, in-

cluding how long it will take to pay the entire balance if only paying the minimum

amount due, as well as disclosure of charges from interest and fees. In addition,

the CARD Act eliminated some practices that were harmful to consumers, like

the retroactive application of higher interest rates on existing balances, and the

administration of hair-trigger late fees. Since President Obama signed the CARD

Act into law in May 2009, it has helped African American households in partic-

ular to pay down debt faster and save money by avoiding unreasonable charges.

Our survey found that more than 9 out of 10 indebted African American

households noticed the change on their monthly statements. More than one-third

adjusted their behavior because of the CARD Act to pay down their balances

faster. irty-seven percent of indebted African American households report-

ed paying more toward their credit card balance as a response to information

in their monthly statements mandated by the CARD Act. (See Table 1)

Another way the CARD Act is helping households take control of their nances

is through the reduction of fees for consumers who outspend their credit limits, or

those who make a late payment. Nearly one-third of African American house-

holds report being charged over-the-limit fees less oen since the Act went

into eect. One in four has been charged late fees less oen. (See Table 1)

e CARD Act also limits the ability of credit card companies to increase in-

terest rates, protecting consumers’ existing balances from retroactively-applied

interest rate increases and ensuring that payments will be applied to the balance

with the highest interest rate rst. As a result, households are less likely to see

hikes in their interest rates. Since the passage of the CARD Act, 25 percent of

African American households have experienced a drop in the interest charges

on their credit card. (See Table 1)

7 • THE CHALLENGE OF CREDIT CARD DEBT FOR THE AFRICAN AMERICAN MIDDLE CLASS

.

Impact of the CARD Act on African American Households

Paid more towards credit card balance in the typical month, as a response

to information on credit card statements mandated by the CARD Act

37%

Charged over-the-limit fees less often 32%

Charged late fees less often 25%

Charged less interest on credit cards 25%

e achievements of the CARD Act for African American house-

holds revealed by our survey make it clear that credit card debtors

need complete information and a fair shot at getting on their feet in

order to make decisions that restore their balance sheets. e provi-

sions of the CARD Act have helped move indebted African Amer-

ican households toward greater nancial freedom and show how a

well-designed policy can have real and positive impacts on peoples’

lives.

December 2013 • 8

The credit card debt basics of

African Americans: balance, APR,

and getting by on debt

T

he nancial crisis of 2007-2008 began in the deregulated credit and se-

curities markets, and reverberated into a global recession. As foreclo-

sure rates escalated, unemployment rose, and credit markets constrict-

ed, Americans responded by tightening their belts and paying down

debt. is study looks deeper into that trend, and nds that while Americans did

indeed deleverage—reducing their average credit card balances in the three years

following the Great Recession—many moderate-income households continue to

rely on credit cards in order to make ends meet.

African Americans owe less than they did in 2008, carrying an average bal-

ance of $5,784 today compared to $6,671 in our 2008 survey. But though these

households are paying down debt overall, more than 4 in 10 African American

households with credit card debt have relied on credit cards to pay for basic living

expenses when paychecks and savings were not enough. Forty-two percent of in-

debted African American households report using their credit cards for basic

living expenses like rent, mortgage payments, groceries, utilities, or insurance

because they did not have enough money in their checking or savings accounts,

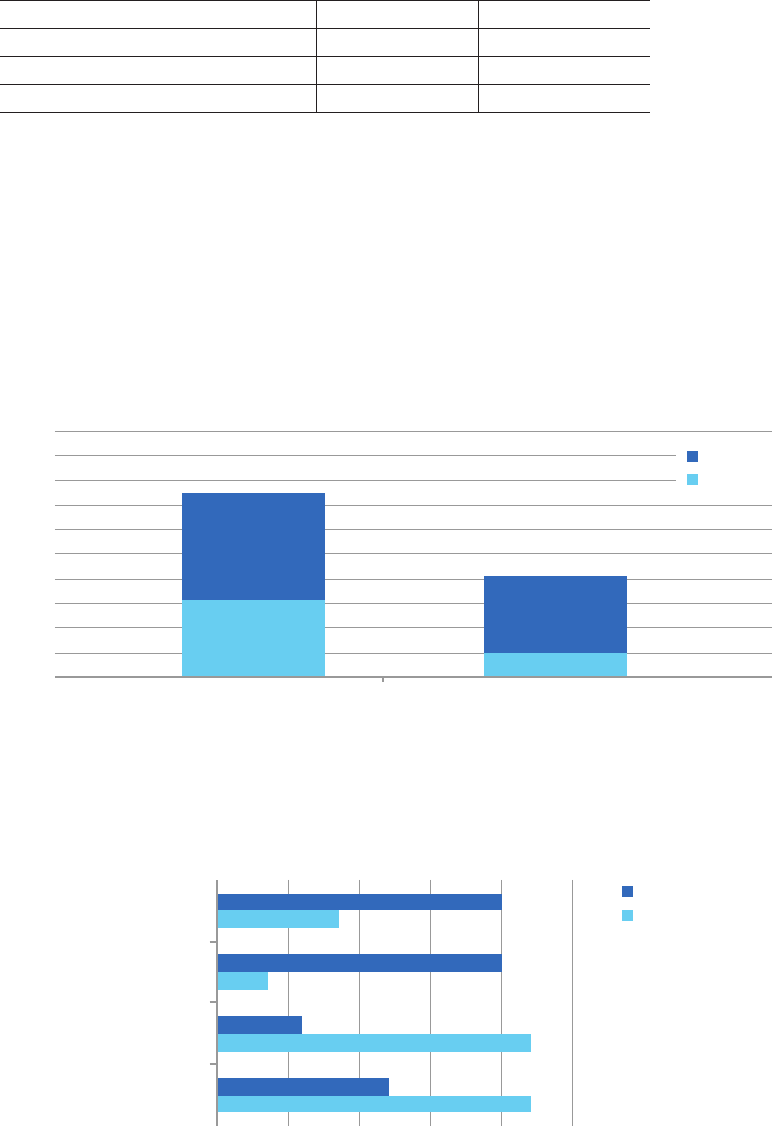

a rate that is similar to white and Latino Americans (see Figure 1).

Relying on debt to deal with emergencies or just stay aoat comes at a cost.

In order to meet monthly payments and work toward reducing debt loads, the

average African American household spends $368 each month on all credit

cards. And over the years required for a household to pay down their credit cards

entirely, interest charges accumulate. African Americans report steep annual per-

centage rates (APRs) adding to their balances and prolonging their debt. Indebt-

ed African American households report an average APR of 17.7 percent on the

card where they carry the greatest balance. Although they carry lower balances,

the high interest rate paid by African Americans results in greater total interest

charges over the duration of a debt. An African American family carrying the

average debt and APR, and that pays the average monthly payment, would be

charged at least $100 more in interest than an average white family, even though

they borrowed less.

9 • THE CHALLENGE OF CREDIT CARD DEBT FOR THE AFRICAN AMERICAN MIDDLE CLASS

.

Average Debt and APR by Race/Ethnicity*

White African American Latino

Average Credit Card Debt $7,315 $5,784 $6,066

Total Monthly Payment on All Cards $609 $368 $483

Average Annual Percentage Rate

of Card with the Highest Balance

15.8% 17.7% 17.9%

.

Households turn to credit cards to make ends meet*

In the past year, have you used credit cards to pay for basic living expenses, such

as rent, mortgage payments, groceries, utilities, and insurance because you didn’t

have money in your checking or savings account?

*Informaon on the average credit card debt and APR by race is provided in order to illustrate the basic credit card debt burden for

indebted households. However, the dierences in total debt, APR, and use of credit cards for basic living expenses between African

American households and white or Hispanic households fall within the margin of error for our survey and are not considered stascal-

ly signicant.

Latino

African-American

0% 15% 20% 25% 30% 35% 40% 45% 50%5% 10%

White

39%

42%

43%

December 2013 • 10

Credit cards fill-in when a

public safety net or private

assets are not available,

leading households to turn

to credit card debt to finance

human capital and other

investments

H

ousehold assets oer a resource for families to weath-

er times of change or uncertainty, as well as the critical

leverage required for families to invest in their futures.

Right now African Americans are facing constraints with

respect to both household assets and income, due to the legacy of dis-

crimination in national asset-building policies that have le African

Americans with just $1 in assets for every $20 owned by whites, and

due to the disproportionate unemployment African Americans have

steadily faced for the last 50 years. African American households on

average have lower incomes and greater rates of unemployment and

underemployment and are less likely than whites to own the most

common asset in the country—a home. e challenges of lower in-

comes, employment, and wealth make it more dicult for African

Americans to leverage long-term investments; in many cases credit

cards may be the best available option. African Americans are more

likely than white households to have credit card debt from the ex-

penses of starting a business, and they are highly likely to carry credit

card debt from paying for a child to attend college and from visiting

the emergency room.

Housing

For those who can aord the investment, the value of home equity

opens a range of possibilities. It is a symbol of middle class success

and the American dream, a secure asset that oers comfort and se-

curity when other problems arise, and a resource that provides the

leverage necessary for making other kinds of investments at lower

costs. Yet according to our survey, just 55 percent of moderate-in-

11 • THE CHALLENGE OF CREDIT CARD DEBT FOR THE AFRICAN AMERICAN MIDDLE CLASS

come indebted African American households are homeowners, compared to

72 percent of white households (see Figure 2). e lower rates of homeownership

among African Americans are both a cause and a symptom of racial asset inequal-

ity. During the post-war era, as the US made signicant investments in the expan-

sion of the middle class, millions of white families enjoyed the public benets of

subsidized housing, suburbanization, and the GI Bill. African Americans instead

faced racially restrictive covenants in private real estate and lending. e prac-

tice of creditor redlining of majority-African American neighborhoods persisted

through the 1980s and targeted predatory lending marred the 1990s and 2000s.

Today, the disparity in homeownership that resulted from these policies continues

to perpetuate racial dierences in other areas, like wealth accumulation, nancial

stability, and access to high quality education and employment opportunities.

Recent research from the Institute on Assets and Social Policy has shown the

racial disparity in homeownership to be the single greatest factor contributing to

wealth inequality, explaining 27 percent of the dierence in the growth of wealth

between white and African American households over the 25 year period from

1984 to 2009. e post-war era policies that oered whites greater opportunities

to build wealth now make it more likely that white families will be able to pass

down an inheritance or oer familial nancial assistance. e disparity is fur-

ther reinforced by dierences in access to credit and the persistence of residential

segregation that lowers the return on investment in African American neighbor-

hoods. As a result of whites’ greater access to familial assets, higher employment

rates, and higher incomes, a white family is likely to purchase a home earlier,

with a larger down-payment and lower fees. e outcome precipitates the average

white family earning equity years before their African American counterparts,

and with higher returns.

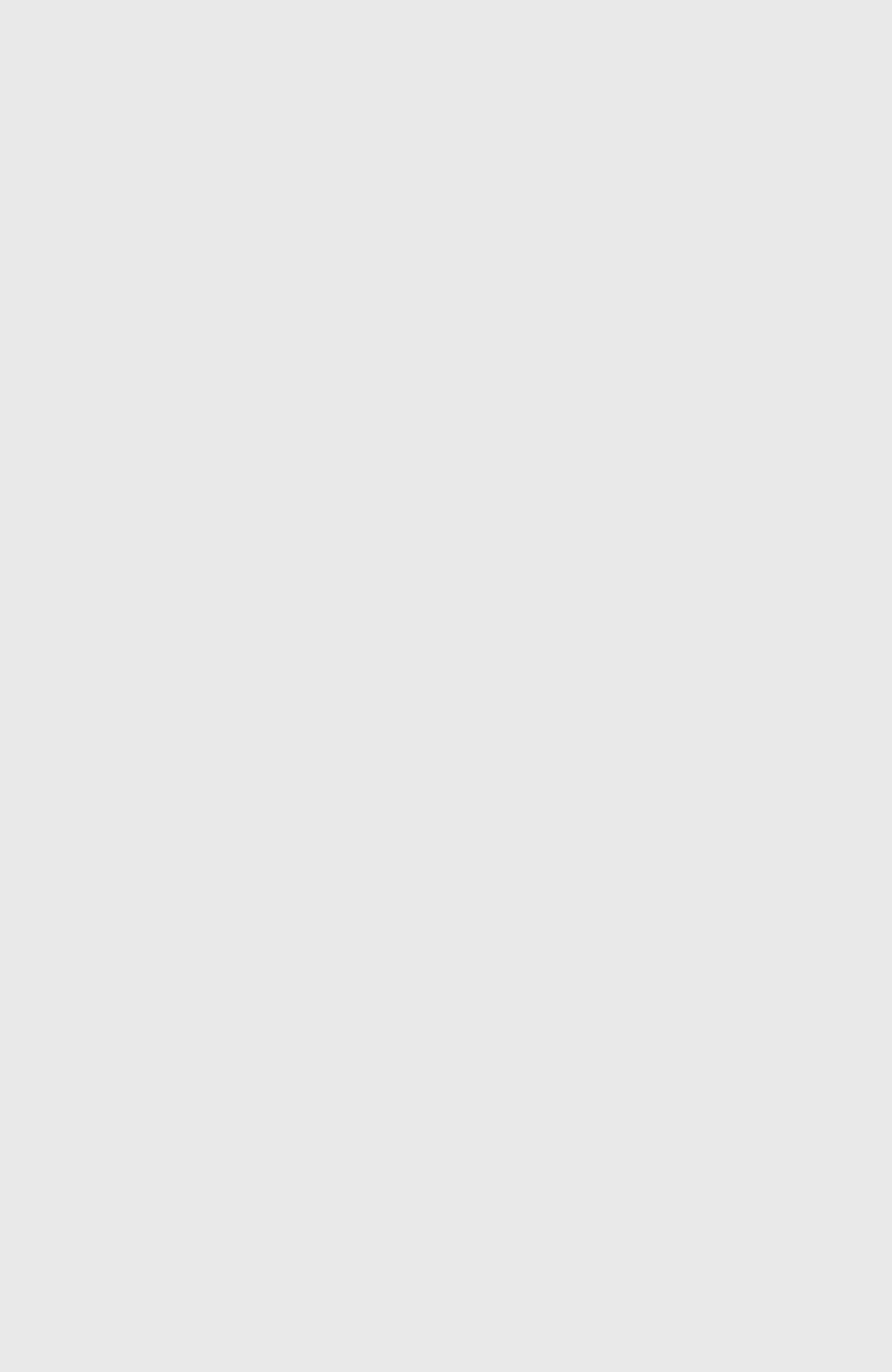

.

African Americans in our survey are less likely to own their homes

Do you currently own or rent your home?

Own

Rent

0% 10% 20% 30%

27%

44%

72%

55%

40% 50% 60% 70% 80%

African American

White

December 2013 • 12

College Education

e rapid rise in tuition over the past 30 years exposed a shi in the Amer-

ican vision of higher education from a public investment to a private expense

—one that many households can only nance by going into debt. College enroll-

ment among people of color grew over the same period, so that African American

and Latino students increased in number just as state spending per pupil declined.

e result is a debt-for-diploma system that lays a greater student debt burden

on African Americans than any other group of college graduates. What’s more,

students are not the only ones who end up carrying the burden of the high cost

of attendance. Student debt oen spills over onto parents, eating into savings ac-

counts or destabilizing other assets. African Americans are more likely to avoid

placing higher education debt on parents’ credit cards than white Americans,

yet our study found that still 50 percent of indebted African American house-

holds who incurred expenses related to sending a child to college report that it

contributed to their current credit card debt.

Young African Americans are more likely to take on debt in order to attend

college, and among those who graduate with student loans African Americans

have the highest balances, with student loan debts thousands of dollars higher

than those of white college graduates. In 2008, student loan debt aected 15 per-

cent more African American graduates than white graduates. Eighty percent

of African American college grads took out some amount of loans in order to

attain a higher education, compared to 65 percent of whites. In the same year,

the average African American senior leaving college with student loans owed

$28,692, compared to $24,742 for whites.

Running a Business

Even before the recession stalled incomes and depleted consumer demand,

asset inequality made it much easier for whites to open and run a business than

for African Americans. e latest Census of small business owners occurred in

2007, before the recession and its associated challenges for entrepreneurs. at

survey showed that between 2002 and 2007 African American-owned businesses

grew at triple the overall rate of business ownership. But despite this rapid in-

crease, African American business ownership is still disproportionately small. In

fact, at the last count African Americans ran just seven percent of all small busi-

nesses in the country, and just 2 percent of those with paid employees. Experts

who study the inequality in small business ownership point to a lack of start-up

capital as a signicant factor in African Americans’ disparate rates of business

success. Moreover, poll aer poll of business owners in the US show that access

to capital remains a challenge for small businesses in general, even 5 years aer

the recession’s end. e credit crunch prompted many banks to shi their small

business lending from nancing through loans to small business credit cards,

which can carry a much higher interest rate than traditional loan options. In ad-

13 • THE CHALLENGE OF CREDIT CARD DEBT FOR THE AFRICAN AMERICAN MIDDLE CLASS

dition, these cards are exempt from the provisions of the CARD Act, leaving busi-

ness owners vulnerable to the abuses that the legislation aimed to curtail, such as

retroactively applied interest charges and unfair late fees. Our survey shows that

African Americans are taking out credit card debt in order to nance their busi-

ness ventures, even though it is more expensive than forms of credit available to

populations with more assets to leverage. We found that 99 percent of indebted

moderate-income African American households who had expenses related to

starting or running a business in the past three years still carry that expense on

their credit card bill, compared to 80 percent of whites (see Figure 3). Nearly all

of the African Americans in our survey who incurred business expenses charged

those expenses to a credit card and have not been able to pay it o.

.

Business expenses contribute to credit card debt (percentage of households

that reported expenses related to starting or running a business in the past 3

years) Did starting a new business or running an existing business contribute to

your current credit card debt?

Health Expenses

Barriers to aordable health care, like the skyrocketing cost of services, make

the possibility of health emergencies a signicant source of economic insecurity

for most Americans. Everyone is at risk of an unplanned health problem, and

without the resources to cover the expense a hospital bill can be a burden on -

nances long aer patients recover. Among the moderate-income households we

surveyed, most incurred some out-of-pocket medical expense such as the cost of

a doctor’s appointment or hospital stay, prescription medication, or a dental ex-

pense. Seventy-six percent of indebted households experienced an out-of-pocket

medical expense in the past 3 years, and most of those families continue to carry

the charge on their credit cards (see Figure 4). e median credit card balance

from health expenditures among African American middle class households

that carry the expense on their credit card is $933. e median indebted African

American household with medical debt on their credit cards carries 11 percent of

their total credit card debt due to medical expenses.

African-American

White

0% 20% 40% 60% 80%

80%

99%

100%

December 2013 • 14

.

Medical expenses contribute to credit card debt*

Did out-of-pocket medical expenses in the past 3 years contribute to your current

credit card debt? How much of your current credit card debt is due to out of

pocket medical expenses? (Median dollar amount)

.

Households sacrifice necessary medical care to reduce expenses*

Have you or a member of your household tried to reduce medical expenses by

doing any of the following?

*African American, Lano, and white households are using credit cards to pay for medical expenses. They are also all forbearing treat-

ment in order to cut down on health costs. The dierences by race and ethnicity for carrying medical debt on credit cards and forbear-

ing care are within the margin of error and not considered stascally signicant. The data are included here in order to illustrate the

contribuon of medical expenses to household debt and the household response to onerous costs across the populaon.

Across demographics, the majority of households with medical debt are turn-

ing to credit cards in order to pay for those expenses. Even households that have

insurance coverage can nd it dicult to aord medical care as the cost of premi-

ums, co-pays, and deductibles rise with health care costs overall. Almost half of all

households in our survey do rely on credit cards to nance out-of-pocket health

care bills like doctor’s appointments, hospital stays, and prescription medications.

In addition to paying for medical expenses through a credit card, half of those sur-

Incurred an out of pocket expense

and that expense did not

contribute to credit card debt

Incurred an out of pocket expense

and that expense contributed to

credit card debt

Median credit card debt from out-

of-pocket medical expenses

0%

0%

10%

Any (Net) Did not ll/postponed

lling a

prescription

Skipped medical test,

treatment or follow up

Did not go to see a

doctor/visit a clinic

when had a medical

problem

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

African American

$933

Latino

$1,521

White

$1,627

47%

39%

36%

32% 32%

50%

38%

30%

40%

36%

59%

51%

African American

White

Latino

15 • THE CHALLENGE OF CREDIT CARD DEBT FOR THE AFRICAN AMERICAN MIDDLE CLASS

veyed are forbearing health care to cut costs. Among indebted moderate-income

African American households, 47 percent have skipped a medical test, treat-

ment or follow-up, did not ll a prescription, or did not visit a doctor when

necessary in order to reduce medical expenses (see Figure 5).

According to the Department of Health and Human Services, the average

emergency room visit costs $1349. For the uninsured that price tag is even

higher, at $1843. For lower income and low wealth individuals this type of cost

can be nancially devastating. e cost burden is particularly problematic for

groups like African Americans, who have higher rates of chronic conditions,

like asthma, that send families to the emergency room, making hospitals an

important resource for critical care. Credit cards can provide the immediate

liquidity that a family needs when faced with an emergency, but the high balance

builds with each month that the debt goes unpaid.

December 2013 • 16

African Americans report

having worse credit scores

C

hanges in the American economy since 1980—including the stagna-

tion of household incomes, escalating expenses as declines in public

investment shied costs onto families, and the loss of workplace ben-

ets, wages, and job security as public policy failed to support the

voice of labor—resulted in credit cards taking on greater importance for family

nances. Today even middle class households are forced to rely on credit card

debt in order to make ends meet when their budgets cannot cover basic needs. At

the same time, borrowing history has become more important to non-nancial

opportunities, as the use of credit reports and scores expands to encompass areas

only loosely, if at all, related to standard lending, including hiring practices and

the provision of essential utilities and medical services. As credit reports and

scores gain importance for non-nancial purposes, new barriers arise for families

trying to take control over their household budgets.

Lower wealth, low rates of homeownership, and higher unemployment rates

put African Americans at a disadvantage for building a solid credit history. More-

over, discriminatory practices—like the predatory lending that targeted commu-

nities of color and contributed to the most recent nancial crisis—reinforce this

racial economic inequality and exacerbate the credit problems of African Ameri-

cans overall. As a result of these factors and others, credit scores are signicantly

correlated with race. Our survey asked indebted households to self-report their

credit scores to the best of their knowledge. We found that African American

households are much less likely than whites to report a good or excellent credit

score (see gure 6). ose reporting bad credit cite a range of issues that contribute

to their low credit scores, and African Americans with poor scores are signicant-

ly more likely than white households with poor scores to report late payments for

their student loans, as well as errors on their credit reports as a cause of bad credit.

African Americans are less likely to report that making late mortgage payments

or maxing-out their available credit contributed to poor scores (see Figure 7). e

results of our survey showing disparities in credit scores and the causes behind

them are part of a growing body of research that suggest a need for signicant

reforms in credit reporting and the widespread use of credit reports and scores

for non-lending purposes.

When asked to identify their credit score within a range, just 66% of African

American households report having a credit score of 620 or above, compared

to 85 percent of white households (see Table 3).

17 • THE CHALLENGE OF CREDIT CARD DEBT FOR THE AFRICAN AMERICAN MIDDLE CLASS

.

African Americans are less likely to report a credit score of 620 or above

What range is your credit score?

White African American

620 And Above 85% 66%

Between 580 and 619 9% 25%

579 And Under 6% 9%

When asked to describe their credit score, only 42 percent of African Ameri-

can households reported having “good” or “excellent” credit, compared to 74

percent of white households. More than half of African Americans report having

“fair” or “poor” credit (see Figure 6).

.

African Americans are less likely to report good or excellent credit scores.

Which Best Describes Your Credit Score?

.

African Americans and whites report some different causes of poor credit

Earlier you mentioned you have a poor credit score, which of the following

contributed to your poor credit score?

0%

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50%

10%

40%

40%

12%

24%

44%

44%

17%

7%

20%

30%

40%

White African American

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

I've been late on my

student loan payments

I have errors on

my credit report

I've used nearly all or all

of my existing credit lines

I've been late with

mortgage payments

Good

Excellent

African American

White

December 2013 • 18

FAIRNESS AND ACCURACY

IN CREDIT REPORTS AND SCORES

Credit history is increasingly important to the economic opportunity of Amer-

ican households, and credit scoring and reporting products are a big industry,

earning billions of dollars per year. Landlords, lenders, and insurance providers

look to credit reports to individually tailor their eligibility and terms of provision.

What’s more, these products are no longer used only to assess individual credit

risk; their use has crept into practices for a number of non-nancial purposes,

such as health care or employment decisions. But credit scores and reports make

poor tools for appraising non-nancial liabilities, and the lack of fairness and ac-

curacy in the products make them unsuitable for many of the functions for which

they are used.

Our study found that moderate-income African American households with

credit card debt are less likely than similar white households to report good or

excellent credit, a nding that aligns with other research identifying racial biases

in credit scoring, including research from the Federal Reserve Board, the Federal

Trade Commission, and the Brookings Institution. Dēmos’ recent report, Dis-

credited: How Employment Credit Checks keep Qualied Workers Out of a Job, also

notes that the credit histories of Latinos and African Americans have suered as

a result of discrimination in lending, housing and employment itself. e poor

credit scores of African Americans relative to whites reect broader conditions of

economic inequality in the US, including the greater likelihood of unemployment

and inadequate insurance coverage among African Americans, and disparities in

wealth accumulation that persist from post-war era policies that favored whites,

as well as more recent discriminatory practices focused in African American

communities, such as redlining and predatory lending. e eects of the Great

Recession, which fell disproportionately hard on African American households,

exacerbate this racial economic divide.

e racial bias in credit histories further undermines the economic opportuni-

ties of African American families as their use grows to encompass areas unrelated

or loosely related to standard lending. Credit reports may dictate the availability

and conditions of acquiring a job or essential services. Employers may eliminate

applicants with credit problems from hiring consideration, even though there is

no evidence for a link between poor credit and poor job performance. Hospitals

and health care providers may examine their patients’ credit reports in order to

evaluate their ability to pay, sometimes even pressuring them to charge medical

bills to credit cards instead of negotiating for better prices. Oen, decisions about

the terms of service and deposit required for basic utilities like heat, water, or

electricity depend on credit reports and can create signicant barriers for families

trying to meet their basic needs.

Biases and inaccuracies in credit reports, and the expansion of the industry to

19 • THE CHALLENGE OF CREDIT CARD DEBT FOR THE AFRICAN AMERICAN MIDDLE CLASS

encompass non-nancial opportunities, reveal the growing need for policy to ad-

dress the problems concerning the use of credit history. Targeted solutions should

include reigning in the use of credit reports and scores for non-lending purpos-

es such as hiring, medical charges, and utility services; removing information in

credit reports that reveals little information about the responsibility of the bor-

rower such as medical debt and payment history on high-risk nancial products;

and increasing the accuracy and transparency of the credit reporting industry.

e Dēmos report Discrediting America examines these issues in greater detail.

A system of credit reporting and scoring that reproduces racial and economic

inequality serves neither lenders nor consumers and increasingly undermines the

economic security of households in areas unrelated to credit. e ndings of the

Dēmos National Survey on Credit Card Debt of Low- and Middle-Income House-

holds reinforce the urgent need for reform.

December 2013 • 20

African Americans are more likely

to be called by bill collectors,

and to have seen credit tighten

A

poor credit score can lead to worsening terms, higher fees, and re-

duced availability of credit. In the most drastic cases it can lead to

harsh consequences for families, like having property repossessed,

being evicted, or declaring bankruptcy. While a few members of our

survey were vulnerable to each of these complications, we found that moder-

ate-income African Americans are far more likely than other groups to be called

by bill collectors as a result of debt. In addition, when faced with higher interest

rates, African Americans were less likely to shi away from credit card use, possi-

bly because they have fewer assets to leverage for necessary spending.

When credit dries up in the economy, consumers with poor credit will feel the

eects rst. Aer the nancial crisis froze credit markets in 2007, lenders tight-

ened the amount of credit available, cutting lines of credit and imposing higher

standards for lending. ose moderate-income families who depend on credit

cards to make ends meet were doubly impacted —facing a severe recession that

both destabilized the households with the lowest incomes and shrank the avail-

ability of credit in the economy. Our survey found that credit-tightening practic-

es hit African American households hardest; more indebted African American

households reported feeling some eects of the credit squeeze on the availability

of credit than indebted white households.

In our survey of moderate-income households who carried credit card debt for

at least three months, there were no signicant dierences in the frequency of

African American and white households declaring bankruptcy, being evicted,

or having property repossessed. African American households were far more

likely than whites to be called by bill collectors as a result of their debt. We

found that 71 percent of African American households had been called by bill

collectors, compared to 50 percent of white households (see Figure 8).

21 • THE CHALLENGE OF CREDIT CARD DEBT FOR THE AFRICAN AMERICAN MIDDLE CLASS

.

African Americans are more likely to be called by bill collectors

Yes responses to ‘Have you ever been called by bill collectors when dealing with

debt?’

We also found no signicant dierences in the number of times African

Americans and whites were late on a credit card payment or faced a higher

interest rate as a result. However, African American and white households re-

sponded dierently when faced with higher interest rates. Looking at comparable

populations who were equally likely to pay their credit card bills on time, Afri-

can Americans were less likely to change the frequency of their card use when

their interest rate increased because of a late payment. While 80 percent of

white households changed their card use, only 62 percent of African American

households made the same change (see Figure 9). e greater likelihood of white

households responding to an increased interest rate by changing their credit card

use suggests that white families are more likely to be able to turn to other options

for short-term liquidity. African American households, in contrast, may not de-

crease their credit card use when interest charges climb because other sources

of liquidity are not available or are even more expensive – like payday loans, for

example.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

50%

71%

80%

White African Americans

December 2013 • 22

.

Despite similar rates of late payment, African Americans are less likely to

change card use when facing a higher interest rate due to late payment

Has getting your interest rate increased because of a late payment changed how

frequently you used the card?

As a response to the nancial crisis, credit card companies curtailed the amount

of credit they would extend and households faced a sudden reduction in credit

availability in the economy overall. Many households who applied for new credit

cards were denied, others had existing credit limits reduced or cards cancelled al-

together. Our survey found that African American households are more likely

to have felt some impact from credit tightening since 2008. Just over half of

African American households reported having a credit card cancelled, credit

limit reduced, or being denied for a credit card in the three years following the

recession (see Figure 10).

.

African Americans were disporportionately impacted by the credit crunch

In the last three years, have you had credit cards cancelled,

credit limit reduced, or applied for and been denied a credit card?

0%

10%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

36%

53%

44%

64%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

62%

80%

20%

38%

Yes

Yes No

No

African American

White

African American

White

23 • THE CHALLENGE OF CREDIT CARD DEBT FOR THE AFRICAN AMERICAN MIDDLE CLASS

Policy Recommendations

T

he American middle class has endured decades of rising costs while

income gains lagged behind. Facing household budget shortfalls for es-

sential spending that expanded over time, families turned to credit card

debt in order to maintain a middle class standard of living. Our survey

reveals that the struggle to make ends meet under diminishing income growth,

private assets, and social investments has led 4 out of 10 households with credit

card debt to rely on their credit cards just to get by.

e economic challenges facing all Americans are only compounded in Afri-

can American households, who over the same period bore the outcomes of racial

discrimination, including slow gains toward equality in income, persistent dispar-

ities in employment, and a widening gap in wealth ownership. While this study

focuses on the particular circumstances of African Americans, the diculties

facing low- and middle-income Americans are widespread and require renewed

consideration of how the nation deals with debt and credit.

e establishment of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and the im-

plementation of the 2009 CARD Act are positive steps toward providing greater

protection for America’s weakened middle class. In addition, state-level policies

like those regulating the use of credit checks for hiring decisions have the capac-

ity to limit unnecessary and harmful barriers to employment. Protections that

establish fair, non-predatory credit practices relieve an already overburdened and

increasingly insecure middle class from the high cost of debt.

e results of our study point to three areas where new policies are required:

medical debt, nancial regulation, and credit scores. We also identify industry

practices that were not addressed by the CARD Act but which remain critical to

the fairness and security of consumer credit.

Medical Debt

MEDICAL DEBT PROTECTION

Emergency health expenses can run into the thousands of dollars and burden

families for years aer they have recovered from the physical trauma. In the de-

cades since the 1970s employers shed health care benets as a provision of em-

ployment and households turned to debt to nance critical health expenditures.

Aer decades without a policy response, the Patient Protection and Aordable

Care Act (ACA) nally oers a solution that can lower the individual cost burden

for health care. Yet medical debt will not cease to exist, and the rising cost of

health services and lower insurance rates among people of color make it dicult

to guarantee adequate coverage and quality of care. Since medical debts continue

December 2013 • 24

to accrue, there must be fair and non-discriminatory practices for their collection.

Medical lending practices should not be permitted to use evaluations of the total

credit available to patients. e appropriate nancial services guidelines for health

care facilities should be under the purview of the Consumer Financial Protection

Bureau (CFPB). Moreover, as unexpected medical expenses oer little informa-

tion about the character of the consumer, medical debt should excluded from

credit scores altogether.

Financial Regulation

BORROWER SECURITY

Many moderate-income African American households rely on credit to make in-

vestments in their futures and oen just to meet their basic needs. Because credit

plays an essential role in the nancial security of Americans, it should be gov-

erned by fair and responsible practices. e CARD Act began the industry re-

forms necessary to establish prudent guidelines and accountability for credit card

companies. Federal legislation protecting borrowers by setting national usury

limits, indexed to a federal rate, would complement the provisions of the CARD

Act. Such legislation would provide borrower security by eliminating unjustiably

high interest rates on credit products ranging from credit cards to student loans

and limiting late fees to $15 per late payment. Several states have already enacted

reforms that cap the interest rates of high-cost payday loans (See State-level pol-

icies for a fair credit market), showing the possibilities for state and local legisla-

tion to regulate the industry and protect consumers.

FAIRNESS IN BANKRUPTCY

Indebted moderate-income African American households need reasonable and

straightforward options as they work toward restoring their balance sheets. As

a last resort, declaring bankruptcy should provide the opportunity for families

to reconcile their debts, including mortgage and student debt. In order to make

bankruptcy a fair option to consumers, bankruptcy law should be amended in

two ways. First, courts should be permitted to restructure the debt on home mort-

gages by setting interest rates and principal at commercially reasonable market

rates and permitted to extend repayment periods. Secondly, judges should be al-

lowed to discharge student loan debt. Our survey found that 40 percent of African

American households that have poor credit scores have seen their scores drop due

to late student loan payments and that half of parents who helped pay for a child’s

tuition still have credit card debt from the expense. Incorporating student loans

into bankruptcy policy will make it possible for families to work for a better future

without being crippled by the cost of education.

25 • THE CHALLENGE OF CREDIT CARD DEBT FOR THE AFRICAN AMERICAN MIDDLE CLASS

DISPARATE IMPACT

As this report notes, African American households with credit card debt face

worse consequences of debt than other groups, including a greater likelihood of

calls from debt collectors. e dierent experiences of African Americans and

whites in the credit market could indicate disparate impact, in much the same way

disparate impact appears in mortgage and auto loan markets. e results of our

survey suggest a need for investigation of predatory lending in the credit market

by the CFPB for evidence of disparate impact.

Credit Scores

FAIR AND ACCURATE CREDIT SCORES

Our survey found that African Americans are far less likely than whites to report

a good or excellent credit score, aligning with a larger body of research show-

ing that credit scores are correlated with race. Moreover, a startling 40 percent of

those with poor credit scores have identied errors on their credit report that con-

tribute to the low score. A stronger role for the CFPB could begin improvements

in the transparency, validity, and appropriate use of credit reports and scores to

ensure accuracy and accessibility of credit reports and the regulation of report-

ing information. In addition, all medical debt, disputed claims, and unsafe credit

products should be excluded from the report. e improvement of reporting and

access would reduce the biases in credit scores and improve the economic security

of both borrowers and lenders.

BAN EMPLOYMENT CREDIT CHECKS

Today, employers commonly look into the credit histories of job candidates as

part of the hiring decision. While there is no evidence linking credit reports to

trustworthiness or dependability, credit reports have repeatedly been shown to

have race and income biases that make the practice of employment credit checks

highly discriminatory. Using credit reports as criteria for hiring exacerbates the

economic hardships facing households that may have had a medical emergency, a

divorce, a layo, or for those that experienced the most severe fallout from an eco-

nomic downswing. Ten states have already passed legislation limiting the use of

employment credit checks because of these issues (see State-level policies for a fair

credit market). We suggest that the US adopt the Equal Employment for All Act,

a federal law establishing uniform restrictions on credit checks for employment.

Extend the Successes of the CARD Act

e CARD Act is working for American households by standardizing best

practices industry-wide. Our research and recent data from the CFPB show that

consumers are better equipped to make informed choices and less subject to

abuses in the areas addressed by the legislation—such as fair and transparent pric-

December 2013 • 26

ing. e provisions of the CARD Act

include protections that grant consumers

better knowledge and control over their

nances, including requiring credit card

providers to make the due dates for pay-

ment the same each month, allocating

payments made above the monthly min-

imum to the highest interest rate balance

rst, and eliminating high-fee over-the-

limit spending unless customers explicit-

ly opt-in to the service. American house-

holds have seized this opportunity to pay

down balances and avoid fees.

Some card issuers responded to the leg-

islation with voluntary product improve-

ments, including an increased commit-

ment to customer service and attention to

received complaints. Yet problems of in-

adequate transparency and injurious costs

remain. In their evaluation of the CARD

Act, the CFPB identied a number of

areas where credit card companies could

promote higher standards of service. e

best practices would treat add-on prod-

ucts, such as supplementary protections

and credit monitoring, with the same

standards of transparency and disclo-

sure as are required for lines of credit,

even when provided through third-par-

ty contracts. Application fees—current-

ly excluded from the standard imposed

by the CARD Act that states fees cannot

exceed 25 percent of the total credit line

in the rst year—would be included in

the rst-year calculation of fees to ensure

that the ratio of costs to credit remains

reasonable. Moreover, a high standard for

clear disclosure related to rewards pro-

grams, grace periods, and products that

defer interest for an introductory period

would complement the practices already

covered by the CARD Act.

STATELEVEL POLICIES FOR

A FAIR CREDIT MARKET

In the absence of eective federal

legislation, consumer groups and

citizens organizations have shown

a way forward for curbing abusive

debt collection practices at the state

level, imposing limits on the inter-

est rates charged by non-traditional

lenders and banning employment

credit checks.

FAIR DEBT COLLECTION

Industries that thrive on abusive

debt collection practices but have

escaped federal legislation can and

should be regulated at the state

level. In many cases, consumer debt

purchased by third-party com-

panies is litigated in state courts

for automatic settlement without

proper notication and transpar-

ency for the buyer. e process

results in debtors, oen unknow-

ingly, faced with nancial penal-

ties and damaged credit reports

that can sabotage their economic

security for years. A 2011 study by

the New Economy Project showed

that in many cases the collection

process deprived the consumer of

their due process rights when debt

buyers brought cases that lacked

legal substantiation but either did

not provide proper notication to

the consumer or intimidated them

into settlement. Following a spate

of unfair collection actions in New

York, the Senate enacted the Con-

sumer Credit Fairness Act in 2013.

e law requires ocial notice of

any legal collection action, including detailed information regarding

the debt in question, and introduces a 3-year statute of limitations

for collection. Similar provisions are included in the Model Family

Financial Protection Act, proposed by the National Consumer Law

Center, and extended to a diverse range of lenders including banks,

credit card issuers, and non-traditional lenders.

REGULATING NONTRADITIONAL LENDERS

e exorbitant interest rates that accompany payday loans—with

rates as high as 400 percent annually—can trap consumers in a

spiral where low income requires increasingly high borrowing, even

for small loans. Although more than 12 million Americans turn

to this source of credit each year, the industry preys on borrowers

in the weakest nancial positions who use the loans for basic living

expenses like rent, utilities, food, and emergency repairs. Strong

usury laws at the state-level can prohibit payday lending entirely,

or restrict it with double-digit caps on the allowable interest rate.

To date, 17 states and Washington DC have enacted legislation cap-

ping the allowable interest rate on payday loans. Other laws limit the

maximum amount and length of borrowing in the industry; accord-

ing to the Center for Responsible Lending, one such law has already

saved consumers more than $122 million in fees. In addition to

direct regulation of non-traditional lenders, states should encour-

age aordable alternatives for the populations most likely to rely on

last-minute emergency loans.

BAN EMPLOYMENT CREDIT CHECKS

Ten states have already passed legislation limiting the use of employ-

ment credit checks. Unfortunately, none of the existing state laws

fully addresses the problem because all include unjustiable exemp-

tions that allow the discriminatory practice to continue in many job

categories. Since one in ve borrowers has a material error on their

credit report, and since poor credit histories are more likely to be

associated with low incomes than personal trustworthiness, the ex-

ceptions can undermine the job prospects of even the most respon-

sible applicants. ose states with legislation that falls short should

move to tighten the laws so that exemptions only exist where there is

a proven link between credit history and job performance. In June of

2013, the New York State Assembly passed one of the nation’s stron-

gest bills on employment credit checks, leaving no inappropriate ex-

emptions. e New York bill provides a guide for state-level action

in the future.

December 2013 • 28

ENDNOTES

1. Rakesh, Kochhar, Richard Fry and Paul Taylor, Wealth Gaps Rise to Record Highs between Whites, Blacks,

Hispanics. Pew Research Center, July 2011, http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/les/2011/07/SDT-Wealth-

Report_7-26-11_FINAL.pdf.

2. omas Shapiro, Tatjana Meschede, and Sam Osoro, e Roots of the Widening Racial Wealth Gap: Ex-

plaining the Black-White Economic Divide. Institute on Assets and Social Policy, February 2013, http://

iasp.brandeis.edu/pdfs/Author/shapiro-thomas-m/racialwealthgapbrief.pdf.

3. GDP measures from the Bureau of Economic Analysis National Economic Accounts, “Current and ‘Real’

Gross Domestic Product,” http://www.bea.gov/national/. Median Income from US Census Household

Income Historical Tables, “Table H-9. Type of Household--All Races by Median and Mean Income: 1980

to 2011,” http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/income/data/historical/household/.

4. Economic Policy Institute. 2012. “Ratio of Black to White Median Family Income, 1947-2010,”. e State

of Working America. Washington, D.C.: Economic Policy Institute, http://stateofworkingamerica.org/

charts/ratio-of-black-and-hispanic-to-white-median-family-income-1947-2010/.

5. Shapiro,et al.

6. Tim Sullivan, Wanjiku Mwangi, Brian Miller, Dedrick Muhammad, and Colin Harris, “e State of the

Dream, 2012: e Emerging Majority,” United for a Fair Economy, January 12, 2012, http://faireconomy.

org/sites/default/les/2012_State_of_the_Dream.pdf.

7. Austin Nichols and Margaret Simms, “Racial and Ethnic Dierences in Receipt of Unemployment In-

surances Benets During the Great Recession,” e Urban Institute, June 2012, http://www.urban.org/

UploadedPDF/412596-Racial-and-Ethnic-Dierences-in-Receipt-of-Unemployment-Insurance-Bene-

ts-During-the-Great-Recession.pdf.

8. Chad Stone and William Chen, “Introduction to Unemployment Insurance,” Center for Budget and

Policy Priorities, February 6, 2013, http://www.cbpp.org/les/12-19-02ui.pdf.

9. DeNavas-Walt, Carmen, Bernadette D. Proctor, and Jessica C. Smith, U.S. Census Bureau, Current Popu-

lation Reports, P60-243, Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2011, Table

A-2, Selected Measures of Household Income Dispersion, U.S. Government Printing Oce, Washington,

DC, 2012, http://www.census.gov/prod/2011pubs/p60-239.pdf.

10. Author’s analysis of 2010 Survey of Consumer Finances public data.

11. Shapiro, et al.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. Tamara Draut, Robert Hiltonsmith, and Catherine Ruetschlin, “e State of Young America: the Data-

book,” Dēmos, November 2011, http://www.demos.org/sites/default/les/publications/SOYA_eData-

book_2.pdf.

16. Robert W Fairlie and Alicia M Robb, “Why are Black-owned Businesses Less Successful than White-

Owned Businesses? e Role of Families, Inheritances, and Business Human Capital,” Journal of Labor

Economics, vol. 25, no. 2 (April 2007), http://people.ucsc.edu/~rfairlie/papers/published/jole%20

2007%20-%20blackbusiness.pdf.

17. US Census, “Survey Small Business Owners: Black-Owned Businesses 2007,” February 8, 2011, http://

www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/business_ownership/cb11-24.html.

18. US Census 2007 Survey of Business Owners, “Statistics for All U.S. Firms by Industry, Gender, Ethnicity,

and Race for the U.S., States, Metro Areas, Counties, and Places,” http://factnder2.census.gov/faces/

tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=SBO_2007_00CSA01&prodType=table.

19. Fairlie and Robb.

20. See, for example, Williams, Vanessa, “Quarterly Lending Bulletin, Small Business Lending: Fourth

Quarter 2012,” Small Business Alliance, January 2013, http://www.sba.gov/sites/default/les/les/

SBL_2012Q4%282%29.pdf. And New York Federal Reserve, “Small Business Credit Survey, May 2013,”

http://www.newyorkfed.org/smallbusiness/2013/pdf/full-report.pdf. And national Federation of Small

Businesses, “Small Business, Credit Access, and a Lingering Recession,” January 2012, http://www.nb.

com/Portals/0/PDF/AllUsers/research/studies/small-business-credit-study-nb-2012.pdf.

29 • THE CHALLENGE OF CREDIT CARD DEBT FOR THE AFRICAN AMERICAN MIDDLE CLASS

21. Catherine Cliord, “Small Business Credit Cards Flourish as Loans Disappear,” CNN Money, October 31 2009, http://

money.cnn.com/2009/10/26/smallbusiness/small_business_credit_cards_loans/.

22. US Department of Health and Human Services, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, Table 6: Emergency Room Ser-

vices-Median and Mean Expenses per Person With Expense and Distribution of Expenses by Source of Payment:

United States, 2010 Facility And SBD Expenses, http://meps.ahrq.gov/data_stats/tables_compendia_hh_interactive.

jsp?_SERVICE=MEPSSocket0&_PROGRAM=MEPSPGM.TC.SAS&File=HCFY2010&Table=HCFY2010_PLEXP_E&-

VAR1=AGE&VAR2=SEX&VAR3=RACETH5C&VAR4=INSURCOV&VAR5=POVCAT10&VAR6=MSA&VAR7=RE-

GION&VAR8=HEALTH&VARO1=4+17+44+64&VARO2=1&VARO3=1&VARO4=1&VARO5=1&VARO6=1&-

VARO7=1&VARO8=1&_Debug=.

23. US Department of Health and Human Services, Oce of Minority Health, “Asthma and African Americans,” http://

minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/content.aspx?ID=6170.

24. See: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, “Report to the Congress on Credit Scoring and Its Eects on the

Availability and Aordability of Credit,” 2007; Federal Trade Commission, “Credit-Based Insurance Scores: Impacts on

Consumers of Automobile Insurance,” 2007; Robert B. Avery, Paul S. Calem, and Glenn B. Canner, “Credit Report Accu-

racy and Access to Credit,” Federal Reserve Bulletin, 2004; Matt Fellowes, “Credit Scores, Reports, and Getting Ahead in

America,” Brooking Institution, 2006.

25. Amy Traub, “Discredited: How Employment Credit Checks Keep Qualied Workers Out of a Job,” Dēmos, February

2013, http://www.demos.org/discredited-how-employment-credit-checks-keep-qualied-workers-out-job.

26. Amy Traub and Shawn Fremstad, “Discrediting America: e Urgent Need to Reform the Nation’s Credit Reporting In-

dustry,” Dēmos, 2011, http://www.demos.org/sites/default/les/publications/Discrediting_America_Demos.pdf.

27. Traub, Discredited.

28. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, “CARD Act Report: A Review of the Impact of the CARD Act on the Consumer

Credit Card Market,” October 1, 2013, http://les.consumernance.gov/f/201309_cfpb_card-act-report.pdf.

29. Ibid,7.

30. Susan Shin and Claudia Wilner, “e Debt Collection Racket in New York: How the Industry Violates Due Process and

Perpetuates Economic Inequality,” New Economy Project, June 2013, http://www.nedap.org/resources/documents/Debt-

CollectionRacketNY.pdf.

31. Robert J Hobbs and Chi Chi Wu, “Model Family Financial Protection Act,“ National Consumer Law Center, June, 2012,

http://www.nclc.org/images/pdf/debt_collection/model_family_nancial_protection_act.pdf.

32. Center for Responsible Lending, “How a Short-term Loan becomes a Long-term Debt,” http://www.responsiblelending.

org/payday-lending/.

33. Pew Charitable Trusts, “Payday Lending in America: Who Borrows, Where they Borrow, and Why,” http://www.pew-

states.org/uploadedFiles/PCS_Assets/2012/Pew_Payday_Lending_Exec_Summary.pdf.

34. Center for Responsible Lending, “How a Short-term Loan becomes a Long-term Debt,” http://www.responsiblelending.

org/payday-lending/.

35. Federal Trade Commission, “Fih Interim Federal Trade Commission Report to Congress Concerning the Accuracy of

Information in Credit Reports,” December 2012, http://www.c.gov/opa/2013/02/creditreport.shtm.

December 2013 • 30