THE NORTH AMERICAN

BANDERS' STUDY GUIDE

A product of the

NORTH AMERICAN BANDING COUNCIL

PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE

APRIL 2001

THE NORTH AMERICAN BANDERS' STUDY GUIDE

Copyright

©

2001 by

The North American Banding Council

P.O. Box 1346

Point Reyes Station, California 94956-1346 U.S.A.

http://nabanding.net/nabanding/

All rights reserved.

Reproduction for educational purposes permitted.

North American Banding Council Banders' Study Guide i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Preface ........................................1

Acknowledgments ................................1

1. Introduction ..................................2

2. The Bander's Code of Ethics ......................2

3. A Brief History of Banding .......................3

4. Purposes and Justification for Banding Birds .........4

4.1. The Banding Offices ......................4

4.2. Purposes and Justification for Banding Birds ....4

4.3. Designing a Research Project ................5

4.4. Cooperative Programs .....................5

5. Permit Issuance ...............................5

5.1. Types of Banding Permits ..................6

5.2. Special Authorizations .....................6

5.3. How to Apply for a Permit ..................6

5.4. Permit Expiration and Renewal ..............6

5.5. Responsibilities of Permit Holders ............6

5.6. Permit Suspensions and Revocations ..........7

6. North American Banding and Recovery Data Base .....7

7. The North American Banding Council ..............7

7.1. What Is NABC Doing? ....................8

7.2. How Will Bander Certification Work? .........8

7.3. NABC Certification .......................8

8. Handling Birds ................................9

8.1. The Bander's Grip ........................9

8.2. The Reverse Grip ........................10

8.3. The Photographer's Grip ..................10

8.4. Free Holds .............................11

8.5. Opening a Bird's Bill .....................11

8.6. Carrying Devices ........................12

8.6.1. Bird bags .........................12

8.6.2. Carrying boxes .....................13

9. Capture Techniques and Extraction Methods ........13

9.1. Setting Up and Operating Mist Nets ..........14

9.1.1. Problems unique to the mist net ........15

9.1.2. Setting up and taking down mist nets ....15

9.1.3. Frequency of net checking .............17

9.2. Extracting Birds from Mist Nets ............18

9.2.1. Feet-first method ....................19

9.2.2. Body-grasp method ..................19

9.2.3. Tricky extraction situations ............20

10. Banding Birds ..............................21

10.1. The Essential Basics .....................21

10.2. Band Fit and Size .......................21

10.3. Types of Bands .........................23

10.4. The Band Numbering System ..............23

10.5. How to Order Bands .....................24

10.6. Banding Pliers and Other Equipment ........24

10.7. Banding a Bird .........................25

10.8. Releasing Birds ........................26

10.9. When and How to Remove a Band ..........26

10.10. Banding Nestlings .....................28

11. Processing Birds .............................28

11.1. Ageing and Sexing ......................28

11.2. Useful Measurements ....................30

11.2.1. Wing length .......................30

11.2.2. Wing formula ......................30

11.2.3. Tail length ........................31

11.2.4. Body weight .......................31

11.2.5. Fat and crop content .................31

11.2.6. Bill length, width, and depth ..........32

11.2.7. Tarsus and foot length ...............32

11.2.8. Crown patch .......................32

11.2.9. Rare birds ........................33

11.3. Parasites ..............................34

11.4. Deformities ...........................34

12. Record Keeping .............................34

12.1. Standard Codes ........................36

12.2. Banding Sheets ........................36

12.3. Recapture Data .........................37

12.4. Banding Schedules ......................37

12.5. Computer verification and edit programs

(MAPSPROG) ...........................39

12.6. Note For File (Canadian) .................39

12.7. Recovery Information ....................39

13. Preventing Bird Injuries and Fatalities ............39

13.1. Safety Considerations for the Use of Mist Nets . 40

13.1.1. Mist net selection and use ............40

13.1.2. Setting up a net array ...............41

13.1.3. Net maintenance and disposal .........41

13.2. Trap and Catching-box Design .............42

13.3. Bird Numbers and People on Hand ..........42

13.4. Injuries and Their Causes .................43

13.5. Causes of Death ........................44

13.6. Treatment of Injured Birds ................45

13.7. Disposition of Dead Birds, Record Keeping,

and Reporting ...........................62

14. Preventing Bander Injuries and Diseases ..........46

14.1. Physical Risks .........................46

14.2. Diseases and Disorders ...................47

15. Visitors and Public Relations ...................48

15.1. Problems .............................48

15.2. Some Solutions ........................48

15.3. Banding Demonstrations for the General Public 48

15.4. Group Visits ...........................49

Selected Bibliography ............................50

Appendix A. Associations and Bird Observatories ......56

Appendix B. Sources of Banding Equipment ..........57

Appendix C. A Well-designed Research Project ........58

Appendix D. Molt Cards .........................60

Appendix E. The Bander's Report Card ..............62

Appendix F. Some Examples of Cooperative Banding

Projects ...................................63

Appendix G. Banding Offices Information ............62

Appendix H. Policy for Release and Use of Banding and

Encounter Data .............................65

North American Banding Council Banders' Study Guide 1

PREFACE

The purpose of this Banders' Study Guide is to provide for

all banders in North America the basic information to safely and

productively conduct bird banding.

This publication is an integral part of several other publica-

tions, including a Trainer's Guide, and taxon-specific manuals

for landbirds, hummingbirds, shorebirds, raptors, waterfowl,

seabirds, and perhaps other groups. While some of the material

in this Study Guide may apply more to certain taxa, the material

was included if it applied to two or more of the taxa mentioned

above. For instance, mist netting is used to capture most taxa

(and thus is discussed in this study guide), but skull pneumatiza-

tion is used primarily for landbirds (and therefore is discussed

only in the landbird manual). Some judgments have been made;

for instance, traps for catching landbirds are mentioned in that

manual, although similar traps are certainly used for shorebirds

and waterfowl. The Committee felt, however, that the special

adaptations required for capture of these quite different taxa

merited separate treatment in the taxon-specific manuals.

We trust that this Guide will be read by all banders and

trainers. While guidelines used by various individual trainers and

stations may differ slightly from the general guidelines set down

in the manuals and guides, we and the North American Banding

Council urge, at the least, that full consideration be given to the

guidelines presented here, and that trainees be fully exposed to

the full variety of opinions that are captured in these publications.

This is a truly cooperative venture, representing many hours

of work of many individuals and their institutions. As such, it

was necessarily an inclusive document covering, as much as

possible, all responsible views of banding in North America. As

can be imagined, this was at times an interesting effort. We trust

that the final product is worthy of the effort that all have put into

it, and of the birds that we study and cherish.

—The Publications Committee of the

North American Banding Council

C. John Ralph, Chair

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank everyone who provided suggestions for the

approach, organization, and content of this guide, in both the

initial Canadian version and in the North American Banding

Council revision.

Greatly involved in the initial version were Ellen Hayakawa,

Peter Blancher, David Hussell, and Lucie Métras of the Canadian

Wildlife Service. Ian Spence kindly allowed the use of training

materials that he has been developing in Britain. Thanks also

to Michael Bradstreet, David Brewer, Douglas Collister, Brenda

Dale, Mark Dugdale, John Pollock, Paul Prior, Rinchen Board-

man, and George Wallace for their helpful insights and com-

ments. Hilary Pittel, a professional bird rehabilitator, shared

many of her insights.

The original guide was prepared under contract from the

Canadian Wildlife Service to Long Point Bird Observatory and

was funded through the Environmental Citizenship Program of

the Department of the Environment.

This North American Banders' Study Guide has been created,

adapted, and considerably augmented for use throughout North

America by the North American Banding Council's Publications

Committee. This guide is very much the product of many years

of collective experience on the part of all the banders and students

at Long Point Bird Observatory, Point Reyes Bird Observatory,

The Institute for Bird Populations, and many other stations and

individuals. It is largely a compendium of material taken from

other sources. Some parts summarize important details presented

in North American Bird Banding: Volume I (Canadian Wildlife

Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1991) and North

American Bird Banding Techniques: Volume II (Canadian

Wildlife Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1977) (see

also http://www.pwrc.usgs.gov/bbl/manual/manual.htm). These

manuals, collectively, hereafter will be referred to simply as the

"Bird Banding Manual." This guide is not intended to supplant

the Bird Banding Manual; they still are required reading.

Technical sections of this guide profited enormously from

The Ringer's Manual (Spencer 1992), The Australian Bird

Bander's Manual (Lowe 1989), A Manual for Monitoring Bird

Migration (McCracken et al. 1993), Handbook of Field Methods

for Monitoring Landbirds (Ralph et al. 1993a), A Syllabus of

Training Methods and Resources for Monitoring Landbirds

(Ralph et al. 1993b), Identification Guide to North American

Passerines (Pyle et al. 1987), Identification Guide to North

American Birds (Part 1) (Pyle 1997a), the MAPS Manual

(Burton and DeSante 1998), the MAPS Intern Manual (Burton

et al. 1999), and the Mist Netter's Bird Safety Handbook (Smith

et al. 1999). These references (and others listed in the Bibliog-

raphy) should be read to gain further insight.

Kenneth M. Burton, Julie Cappleman, Brenda Dale, David

F. DeSante, Erica H. Dunn, Lisa Enright, June Ficker, Dan

Froehlich, Geoff Geupel, Mary Gustafson, John Hagan, Kathy

Klimkiewicz, Jon D. McCracken, Lucie Métras, Sara Morris,

Robert S. Mulvihill, T. Pearl, Paul Prior, David Shepherd, Otis

D. Swisher, Jennifer Weikel, and Bob Yanick contributed major

portions of this document. Final editing and quality control of

this study guide were done by Jerome Jackson, Glen Woolfenden,

and Jared Verner. We are all grateful for their conscientious and

effective help.

—Publications Committee

2 North American Banding Council Banders' Study Guide

1. INTRODUCTION

Bird banding is both a delicate art and a precise science. It

should come as no surprise that it requires not only sensitivity and

intelligence, but also training. This is in the interest of the birds'

safety and in the interest of gathering accurate and useful

information.

Nearly all beginning banders are nervous and a little

awkward. This is a good sign because it signals that you

understand that you are holding something very much alive and

precious. After a time, though, it is all too easy to become

complacent. A good bander is always on guard against compla-

cency and realizes that, above all, banding is a great privilege.

The North American Banders' Study Guide and The In-

structor's Guide to Training Passerine Bird Banders in North

America are designed to complement each other. All banders and

prospective banders should familiarize themselves with the infor-

mation presented in the Study Guide. The Instructor's Guide,

however, is generally available only to trainers.

The motivating factor in the production of these guides is the

safety and welfare of the birds involved. Indeed, this principle

takes precedence over all other considerations in any kind of

banding operation.

You may want to band birds only as a small part of a short-

term research project, perhaps focusing on a single species, or you

may plan to use banding as a major part of your future work. In

either case, responsibilities are the same and you need the same

basic skills. Some people will need only limited training. For

example, if you are banding only geese, it probably does not really

matter whether you can tell a robin from a Blue Jay. Your trainer

can recommend that a banding permit be limited to a certain

species or trap type, or issued for use on a specific project only.

Training must be by a qualified trainer. The North American

Banding Council (NABC) maintains a complete listing of NABC-

certified trainers in specific geographic regions. For information

on NABC, contact the Banding Offices or web site (http://naband-

ing.net/nabanding/).

The amount of training required depends on the nature of

your project, the type of permit you want to acquire, the speed at

which you learn, the accessibility of a good trainer, and the

availability of training opportunities. It is difficult to establish

quantitative guidelines regarding how much time is required or

how many birds need to be handled. If you think you need a

permit in a hurry, remember that basic training is still a

requirement, and you should plan for this. This is particularly

relevant to graduate students, who should allow sufficient time

for thorough training.

In a NABC-approved evaluation procedure, a trainer must

assess a student's knowledge and practical skills, following

completion of a step-wise training program. The trainer grades

students according to the specifics of the banding project that they

will do. Some students will have specific research projects (e.g.,

graduate students studying a single species), while others will

have much broader interests (e.g., personnel at bird observato-

ries). Your permit should reflect the specifics of your research,

and you must inform your trainer of any special needs you might

have.

Along with a training manual, trainers are supplied with a

"Bander's Report Card" to guide the assessment process. A copy

of this report card is provided as Appendix E in this manual, to

give an overall feel for the content and structure of a thorough

training program.

Much information is presented in this guide. Students must

read it over at least once before their training to orient themselves

and preview what will be learned. After a week or two of

training, it should be reviewed in its entirety.

What makes for a good student? A good student is never

afraid to ask questions or to insist on adequate training time.

First observe, then perform each task under supervision. Learn

each new step openly in front of your trainer, so that he or she

can see exactly what you are doing. Once you are permitted to

do certain things alone, have your trainer spot-check you to see

that you are not developing bad habits and to ensure that your age

and sex determinations and measurements are reliable. "Brush-

up" sessions with your trainer after a few weeks or months on

your own can be very helpful. Don't get arrogant or over-

confident; a good bander has a life-long attitude that there is

more to learn, and recognizes that everyone, even the most

experienced, can make a mistake now and then. Keep your

humility. At the same time, confident handling is important to

bird safety and that's what we want you to learn.

2. THE BANDER'S CODE OF ETHICS

Bird banding is used around the world as a major research

tool. When used properly and skillfully, it is both safe and

effective. The safety of banding depends on the use of proper

techniques and equipment and on the expertise, alertness, and

thoughtfulness of the bander.

The Bander's Code of Ethics applies to every aspect of

banding. The bander's essential responsibility is to the bird.

Other things matter a lot, but nothing matters so much as the

health and welfare of the birds you are studying. Every bander

must strive to minimize stress placed upon birds and be prepared

to accept advice or innovation that may help to achieve this goal.

Methods should be examined to ensure that the handling time

and types of data to be collected are not prejudicial to the bird's

welfare. Be prepared to streamline procedures of your banding

operation, either in response to adverse weather conditions or to

reduce a backlog of unprocessed birds. If necessary, birds should

be released unbanded, or the trapping devices should be

temporarily closed. Banders should not consider that some

mortality is inevitable or acceptable in banding. Every injury or

mortality should result in a reassessment of your operation.

Action is then needed to minimize the chance of repetition. The

most salient responsibilities of a bander are summarized in the

Bander's Code of Ethics; more details are found in Section 13.

Banders must ensure that their work is beyond reproach and

assist fellow banders in maintaining the same high standards.

Every bander has an obligation to upgrade standards by advising

the Banding Offices of any difficulties encountered and to report

innovations.

Banders have other responsibilities too. They must submit

North American Banding Council Banders' Study Guide 3

their banding data to the Banding Offices promptly, reply

promptly to requests for information, and maintain an accurate

inventory of their band stocks. Banders also have an educational

and scientific responsibility to make sure that banding operations

are explained carefully and are justified. Finally, banders

banding on private property have a duty to obtain permission

from landowners and to make sure their concerns are addressed.

3. A BRIEF HISTORY OF BANDING

The first recorded instance of bird marking dates back to

about 200 BC when marked birds were used as messengers by

the military and sportsmen. Until the inception of systematic,

scientific bird banding in Denmark in 1899, all attempts to mark

birds were individualistic, involving the use of nonstandard

markers such as colored string, paint, metal shields around the

neck or tarsus, and toe clipping.

Ernest Thompson Seton and John James Audubon are

acknowledged as the first "banders" in Canada and the U.S.,

respectively, even though they did not use bands. Audubon tied

silver wire around the legs of nestling Eastern Phoebes in

The Bander's Code of Ethics

1. Banders are primarily responsible for the safety and welfare of the birds they study so that stress

and risks of injury or death are minimized. Some basic rules:

- handle each bird carefully, gently, quietly, with respect, and in minimum time

- capture and process only as many birds as you can safely handle

- close traps or nets when predators are in the area

- do not band in inclement weather

- frequently assess the condition of traps and nets and repair them quickly

- properly train and supervise students

- check nets as frequently as conditions dictate

- check traps as often as recommended for each trap type

- properly close all traps and nets at the end of banding

- do not leave traps or nets set and untended

- use the correct band size and banding pliers for each bird

- treat any bird injuries humanely

2. Continually assess your own work to ensure that it is beyond reproach.

- reassess methods if an injury or mortality occurs

- ask for and accept constructive criticism from other banders

3. Offer honest and constructive assessment of the work of others to help maintain the highest

standards possible.

- publish innovations in banding, capture, and handling techniques

- educate prospective banders and trainers

- report any mishandling of birds to the bander

- if no improvement occurs, file a report with the Banding Office

4. Ensure that your data are accurate and complete.

5. Obtain prior permission to band on private property and on public lands where authorization is

required.

4 North American Banding Council Banders' Study Guide

Pennsylvania in 1803 and was lucky enough to have the first

returns in North America when he caught two of his nestlings

again the next spring. In Canada, Seton marked several Snow

Buntings with printer's ink in 1882 in Manitoba.

Key to the development of a continent-wide banding and

recovery program was the formation and acceptance of a single

concept; namely that, with the cooperation of North American

ornithologists, the capture, marking, and subsequent encounters

of individual birds would lead to invaluable data on species'

habits, migration routes, and population status. Leon Cole was

the first to publicly and formally introduce scientific bird banding

to North America at a Michigan Academy of Science meeting in

1901, but it was P.A. Taverner who initiated the centralized

distribution of standardized, aluminum bands. In 1904, Taverner

placed a note in the Auk, offering bands to ornithologists wishing

to cooperate in a banding project. James H. Fleming of Toronto,

Ontario, was the first to use these bands, in 1905.

In 1909, the American Bird Banding Association (ABBA)

was formed. As a central organization whose role was to oversee

the issue of standardized bands as well as the collection and

storage of the resulting banding data, the ABBA greatly

contributed to the efficiency of the banding program. In 1911,

the Linnaean Society of New York offered to administer the

banding program for the ABBA, helping to cover the rising

administrative costs of the program.

With the signing of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act in 1916

came increased cooperation between Canada and the U.S. and

the recognition that migratory birds were of international

concern. The development of the banding scheme continued

under the direction of the Bureau of Biological Survey of the U.S.

Department of Agriculture in 1920. In 1922, Canada's Dominion

Parks Branch became officially involved, and by 1923 the

Canadian government was responsible for the administration of

banding efforts in Canada. Bands were standardized throughout

North America and each country became responsible for its own

banding data. Now, the U.S. Geological Survey and Canadian

Wildlife Service are jointly responsible for administration of the

North American banding program.

4. PURPOSES AND JUSTIFICATION FOR

BANDING BIRDS

4.1. The Banding Offices

The work of the Bird Banding Offices in Canada and the U.S.

is closely coordinated. Each office acts as a center for the

administration of banding within its own country, reviewing

proposed banding projects, and issuing bands, auxiliary markers,

and banding permits to qualified banders. All banding and

recovery data are computerized and freely exchanged between

offices. Each country encourages the use of the database by

banders and researchers. In so doing, the offices promote the

publication of significant findings resulting from bird banding.

However, banding birds is not a conservation or research program

in itself. The Canadian Wildlife Service and United States

Geological Survey do not have a conservation program called

"bird banding," and neither government has researchers looking

at data collected from banding. Hence, banders are not making

a bona fide contribution to research if they are banding birds only

for the purpose of contributing to the North American database

on banding and recovery. While all banding data are potentially

valuable, the value of banding data increases enormously if it is

collected under a well-designed study or is part of a cooperative

program. We strongly encourage all banders to think hard about

the usefulness of the information being gathered. Banders are

obliged to ensure that their study design and the collection and

analysis of data are sound, and that their results are published.

The Banding Offices review all applications for permits. If an

application is turned down because it lacks scientific merit, this

decision should be respected.

4.2. Purposes and Justification for Banding Birds

As detailed in Buckley et al. (1998), the basic purposes and

justification for banding birds are its scientific merits: it provides

data vital for scientific research into bird populations and for the

conservation and management of those populations. While some

of these data can be provided in other ways, banding often

remains the most cost-effective approach. Banding, recovery,

recapture, and resighting data remain critical for the conservation

and management of birds. Their use in the setting of annual

species and bag limits for game birds provides an immediate and

widely appreciated example. At the level of basic scientific

knowledge, banding is also a valuable tool for obtaining

information about avian populations, movements, behavior, etc.,

regardless of any immediate conservation or management value.

Lastly, banding has legitimate and widespread educational values

over and above its scientific value.

It is not always appreciated, especially by governmental

bodies and the public, exactly how valuable good banding data

are, and the important uses to which they are routinely put.

Examples include:

(1) Providing knowledge about movements of birds—e.g.,

establishing migration routes, finding links between

breeding and wintering grounds, delineating separate

populations, tracking range expansions and colonizations,

measuring dispersal within populations, quantifying gene

exchange among populations;

(2) Estimating demographic parameters and determining

dynamics of bird populations—e.g., estimating annual

production of young birds or age-dependent annual survival

rates, building models of population dynamics for predicting

extinction probabilities, separating population sources and

sinks, comparing survival rates of experimental or rehabili-

tated birds to those of wild birds;

(3) Management of gamebirds—e.g., delimiting flyways;

estimating harvest pressure for input to the establishment

and modification of hunting regulations; measuring

differential vulnerability to harvest and other risks by

species, age, sex, and geographic location;

(4) Ecological research requiring individual recognition—e.g.,

estimating territory size and examining the importance of

migrant stopover areas through individual stopover time

and weight gains, as well as habitat selection, dominance

hierarchies, molting strategies, molt patterns, and the

parasite burdens of individuals;

North American Banding Council Banders' Study Guide 5

(5) Monitoring populations and individuals—e.g., monitoring

Endangered or Threatened species, identifying populations

declining from decreased reproductive output or from dim-

inished recruitment, establishing population trends, and

validating other techniques of population monitoring;

(6) Educating the public about science and birds—e.g., teach-

ing, in the hand, about birds, their movements, their plu-

mage differences, and how molt proceeds; reinforcing

stewardship responsibilities.

We emphasize that the maximum value of banding data is

realized only when: (a) accurate and standardized (or well-

documented) data are taken; (b) these data are stored centrally

and made readily available to analysts and researchers; and (c)

the data are used, and the results are published.

Over 1.2 million bands are issued annually in the North

American Bird Banding Program. With so many birds involved,

the program inevitably incurs casualties. Some birds are injured

or die as a result of predators, or of being trapped, handled, or

banded. In all careful banding programs, the numbers are small

relative to those banded, but every effort must be made to reduce

the number to as near zero as possible. These losses can be

minimized by increasingly effective training in the capture,

handling, and welfare of birds, and by certification of banders.

The North American Banding Council's Bander Certification

Program addresses these issues.

4.3. Designing a Research Project

Banders may conduct research in two ways. You can design

your own research project and analyze your own data in the

context of the project's design, or you can collaborate with others

who have already designed projects (many of which are usually

in need of skilled assistance).

If you wish to set up your own research project and analyze

your own data, you will need to understand basic statistics (e.g.,

the mean, probability theory). Among other things, statistics can

be used to determine average dates of arrival, significantly early

or late occurrences of a species, and the proportion of hatch-year

birds to adults in a given population. Zar (1984) and Sokal and

Rohlf (1994) are both good statistical textbooks, but they are not

written for the lay-person. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

and the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) have produced

excellent introductory guides to ornithological statistics (Fowler

and Cohen, undated; Nur et al. 1999); see Appendix B for the

BTO address.

Grubb (1986) is a good reference on designing simple realistic

studies. Good examples of well-designed projects can be found

in journals like North American Bird Bander, Journal of Field

Ornithology, and Ringing and Migration. An example of a well-

designed research study is outlined in Appendix C.

Project design proceeds through a series of logical steps:

(1) Ask a question. All well-designed projects focus on a well-

defined question. Depending on the question, this step

usually implies some familiarity with the work of others on

the subject. Recently published literature can be consulted

at a university library.

(2) Develop a hypothesis. A hypothesis combines the question

with your expectation of what the answer might be and why.

Much of the necessary theoretical background for forming

a hypothesis comes from studying the results of others.

(3) Propose and design a project. Most people need help at this

stage. To design a workable project, you need to determine

what kinds of, and how many, data need to be collected.

This is where statistics can help. Usually the statistical test

that will be used to analyze the data dictates, to some extent,

the types and sample sizes of data required for analysis. At

this stage, banders should have a clearly formulated

question, with a hypothesis, a plan for collecting the neces-

sary data, and a plan for the statistical analysis of the data.

An experienced researcher or statistician can confirm that

the proposed sample size and types of data are sufficient for

meaningful tests of the hypothesis. Banders who are exper-

ienced with the capture of the proposed species can confirm

that the target number and trapping method are easily

attainable over the duration of the study. Get others' opin-

ions on the possible limitations of your study; it will save a

lot of hardship later.

(4) Collect the data. This is often the most challenging step

because field conditions rarely match expectations. Good

planning and appropriate practical training will greatly

facilitate this step.

(5) Analyze the data. The use of a computer with data entry and

statistical analysis programs will make analysis much easier.

(6) Publish your results. Remember that "negative" results are

just as important as "positive" results because they allow you

and others to build upon them. A range of publication outlets

is available, from regional bird bulletins to international

research journals.

(7) Questions beget more questions!

4.4. Cooperative Programs

Many scientific studies could never be undertaken at an

adequate scale by individual banders; they are possible only as

collective endeavors. Hence, even if you do not have a specific

project yourself, you can still contribute meaningful information

to a larger, organized project. Contact the universities, Partners

in Flight, and bird observatories, or respond to bulletins in

journals or newsletters such as the one published by the Ornitho-

logical Societies of North America (OSNA) for information on

how you can help. The OSNA newsletter can be viewed online

at http://www.ornith.cornell.edu/OSNA/ornnewsl.htm. Coopera-

tive projects in North America are described in Appendix F.

5. PERMIT ISSUANCE

Because bird welfare is a primary concern, banding permits

are issued only to people who have received proper training and

whose projects are designed to contribute to the knowledge,

conservation, and management of North American bird popula-

tions. Permit authorizations can be very specific. For example,

your banding permit may restrict you to banding young Herring

Gulls captured by hand. A more general permit could authorize

you to run a general bird monitoring station, with special

authorizations for the use of mist nets and for banding a wide

variety of species. Before applying for a permit, banders should

be confident of their qualifications and know which authoriza-

6 North American Banding Council Banders' Study Guide

tions are needed to complete their project. Consideration should

be given to the species under study, the capture method, and type

of data needed.

5.1. Types of Banding Permits

Two types of federal banding permits are available: the

Master Permit and the Subpermit. The differences between the

two relate to the experience and qualifications of the bander and

the responsibilities to be assumed. Because it costs money to

process banding and recovery data, it is more efficient if banding

teams or organizations designate one responsible person to report

all banding data. Although this section will deal with federal

banding permits, banders should be aware that some states and

provinces have separate permit requirements. Banders need to

contact their state or provincial wildlife agency for information

on state or provincial permits. A listing of all state Department

of Natural Resources offices can be located on the internet at

http://www.up-north/dnr_news/dnrstates.html. It is the bander's

responsibility to obtain all required permits before banding.

Master Permits are issued to "responsible individuals"

banding on their own or designated from a team of banders who

are working together on a project. Master Banders are responsi-

ble for coordinating the activities of all Subpermittees within the

project, ordering and distributing bands from the Banding Office,

recommending new Subpermittees, reporting encounters, and

preparing banding "schedules" (see Section 12.4).

Organizational Master Permit projects (e.g., at universities

and bird observatories) are overseen by a designated individual

who is granted Subpermit "A" within the organization's Master

Permit. In this case, the organization's address is used on all

correspondence with the Banding Offices so that data can be filed

in a consistent manner, despite possible personnel changes within

the organization.

Subpermits are issued to banders guided and supervised by

a Master Bander. Data from all Subpermittee banding are filed

in the Banding Offices under the Master Permit's number.

Note that banders and students do not require a permit if they

are under the direct, on-site supervision of a Permit holder.

Banders working unsupervised for any period of time, however,

do require a subpermit.

Contact the appropriate Banding Office (Appendix G) for

permitting standards, requirements, and application materials and

procedures.

5.2. Special Authorizations

Banders must request special authorization to:

(1) band waterfowl

(2) band hummingbirds

(3) band endangered species (and provincially protected species)

(4) use mist nets

(5) use cannon nets

(6) use chemicals (i.e., tranquilizers) to capture migratory birds

(7) use auxiliary markers (e.g., color bands, radio transmitters)

(8) take blood or feather samples

In Canada, banders also must request special authorization

to band raptors, or to band in a federal or provincial park, a bird

sanctuary, or in a wildlife area.

A banding permit allows banders to salvage dead birds

encountered during their studies. Specimens are useful for

further study and they should be salvaged whenever possible (e.g.,

sent to museums, universities). However, a special permit is

required to collect birds, to hold or transport live birds, and to

possess specimens, including eggs and nests. Without this

special permit, you can be charged with an offense. Permits to

cover these activities can be requested from your regional U.S.

Fish and Wildlife Service Migratory Bird Office; see http://-

www.pwrc.usgs.gov/bbl/manual/mboffice.htm for contact infor-

mation.

5.3. How to Apply for a Permit

Qualified persons wishing to handle, band, or mark birds in

North America should ask for an application form from the

appropriate Banding Office (see Appendix G). Master Banders

should supply the names and addresses of all prospective

Subpermittees when they ask for Subpermittees' application

forms. When a request for a permit is received by the Banding

Offices, an acknowledgment letter is sent with an application

form and a request for any necessary additional information. The

Banding Offices review applications for permits and issue when

appropriate.

5.4. Permit Expiration and Renewal

In general, banding permits are valid for 2 calendar years.

In the U. S., Master Banders are contacted at renewal time if

banding activity has been limited. In Canada, a renewal ques-

tionnaire is sent to Master Banders each December and upon

submission of banding data.

In the U.S., auxiliary authorizations are reviewed and

renewed every 2 years. In Canada, banding permits are issued

for 1 or 2 years depending on the projects. When a project

includes the use of auxiliary markers other than colored bands,

an annual Animal Care Committee review and approval is

required. All other banding permits are issued for 2 years, but

Master Permittees must submit a Year-end-report at the end of

each year to inform the Banding Office if changes are required

to their current banding permit.

5.5. Responsibilities of Permit Holders

Master Permit holders are responsible for their Subpermittees'

qualifications and conduct. Master Banders order all bands,

maintain a band inventory, submit all records to the Banding

Offices in a timely manner, maintain updated copies of all

banding schedules, report recoveries, maintain quality control,

and generally handle all paper work associated with the permit.

Subpermit holders are under the direction of the Master Bander,

who decides upon individual responsibilities. At the very least,

Subpermittees must provide the Master Bander with copies of all

banding schedules and band inventories and keep the Master

Bander advised on any problems that might arise. Subpermittees

also must let the Master Permit holder know their band require-

ments in plenty of time to allow band orders to be placed and

filled.

All Master Permit holders are responsible for the bands issued

to them until the data resulting from their use are reported, the

bands are returned to the Banding Offices, or they are transferred

to another Bander. All transfers must be authorized by the

North American Banding Council Banders' Study Guide 7

Banding Offices. In case of fire, theft or loss of bands, a copy of

all band numbers received should be kept in a couple of different

places. Band inventories should be done at the end of each

banding season.

Banders should always double check that the bands they have

received correspond to the bands issued to them, as listed on the

Banding Offices' Issue Slip. This means checking the numbers

on the bands themselves, not just the numbers printed on the band

envelopes or boxes. In the case of a discrepancy, or if any band

numbers are illegible, missing, duplicated, or out of order, notify

the respective Banding Office immediately.

5.6. Permit Suspensions and Revocations

Permits may be suspended or revoked if the bander's

qualifications or conduct are questioned, investigated, and

subsequently found to be in breech of those deemed acceptable

by the Banding Offices. This includes exceeding authorizations

specified on banding permits, neglecting to submit banding

schedules, or the mistreatment of birds.

6. NORTH AMERICAN BANDING AND

RECOVERY DATA BASE

Banding and encounter data are gathered and stored for the

purpose of facilitating research in North America. Researchers

are encouraged to request data for analysis. Generally, this

information is provided free of charge for those with legitimate

research purposes.

Banding and encounter data are contained in their own files

and in the Banding Retrieval File and the Encounter Retrieval

File, respectively. Data are taken directly from the retrieval files,

presented in the formats shown in the Banding Manual, and

supplied to you on diskette or as an electronic attachment. The

Banding Offices will not usually summarize or tabulate data for

you. However, occasionally the information may have already

been tabulated by other researchers and can be made available

upon request. The Banding Offices have developed their own

programs for data manipulation. You may be able to make use

of these programs for data summation.

To release banding or encounter data, the Banding Offices

require that the need for use of the data is justified. The Offices

also need to know whether data are required from the Banding

Retrieval File, Encounter Retrieval File, or both, the type of

encounter data required, species, age and sex required, area and

time period involved, and the various status and additional

information codes desired (consult the Bird Banding Manual

[Canadian Wildlife Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

1977, 1991] for more detail).

Much time and effort goes into data collection and storage,

both on the part of those who contribute data and those who

administer the banding program in North America. Researchers

are therefore asked to use data with care and consideration.

Researchers using banding data must obtain permission from

the banders involved before their data can be used for

publication, specifically, if a bander's past 5 years of banding

or encounter data contribute 5% or more of the total records

being used for publication, and/or if individual banding or

reencounter records will be cited in the paper. This permission

is seldom difficult to obtain, but it is necessary to protect banders'

own research interests. Banders have the prior right to the

analysis and publication of data resulting from their own banding

efforts. To guard against the improper use of data, a Policy of

Release is included with each data request. A copy of the "Policy

for Release and Use of Banding and Encounter Data," updated

September 24, 1998, is presented in Appendix H.

Data on endangered, threatened, or sensitive species may be

legitimately withheld by the Banding Offices. Other data also

may be withheld if they are required by government for manage-

ment or administrative purposes.

7. THE NORTH AMERICAN BANDING

COUNCIL

The mission of the North American Banding Council

(NABC) is to promote sound and ethical bird banding principles

and techniques in North America. Skill levels of banders will

be increased by the preparation and dissemination of standardized

training and study materials and the establishment of standards

of competence and ethics for banders and trainers.

The immediate objectives are:

(1) to develop a certification and evaluation program by setting

standards for experience, knowledge, and skills that must

be attained at each level (Assistant, Bander, and Trainer);

(2) to produce and update training materials such as manuals

and perhaps videos;

(3) to identify and certify an initial pool of trainers; and

(4) to encourage cooperative efforts in the use of banding in the

study and conservation of North American birds.

The NABC consists of 18 to 20 voting members, including

one representative appointed by each of the following organiza-

tions: American Ornithologists' Union, Association of Field

Ornithologists, Cooper Ornithological Society, Colonial

Waterbird Society, Eastern Bird Banding Association, Inland

Bird Banding Association, Ontario Bird Banding Association,

Pacific Seabird Group, Raptor Research Foundation, Society of

Canadian Ornithologists, Western Bird Banding Association,

Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network, and Wilson

Ornithological Society; and two representatives appointed by the

International Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (one

from Canada and one from the United States). Other groups have

been invited to become affiliated. The NABC also designates

from four to six additional members. The directors of the

Canadian and U. S. Bird Banding Offices are non-voting

members of the NABC. The NABC was incorporated as a non-

profit California corporation in 1998. While it is expected that

the NABC expenses will be covered by a small fee from appli-

cants for banding certification, donations are being solicited

during this start-up phase.

8 North American Banding Council Banders' Study Guide

7.1. What Is NABC Doing?

The NABC has developed a bander training and certification

program to set standards of knowledge, experience, and skills at

two banding skill levels: Bander and Assistant.

The NABC has prepared training manuals to serve as

reference materials for trainers and prospective new banders, and

to enhance the knowledge and skills of existing banders. The

current ones are: North American Banders' Study Guide,

Instructors' Guide to Training Passerine Bird Banders in North

America, Guide to the Banding of North American Raptors, The

North American Guide for Passerines and Near Passerines, and

North American Bander's Manual for Hummingbirds. Other

manuals are anticipated. Printed and electronic versions will be

produced in cooperation with the Banding Offices.

In addition, the NABC has designated a group of Trainers

who have extensive experience, peer recognition as expert

banders, good teaching abilities, and high ethical standards. The

NABC also maintains procedures, policies, and bylaws; issues

certifications; updates training and testing materials; and

maintains a directory of certified assistants, permittees, and

trainers.

7.2. How Will Bander Certification Work?

Certification of banders will require passing a written test and

field evaluation of banding skills. Prospective banders may

contact NABC or the Bird Banding Offices for information.

Existing banders also may wish to be certified. NABC certified

trainers will certify banders at all levels. Some trainers may be

involved in teaching formal courses. NABC will issue and

register the formal certifications. Modest fees will be charged to

cover administrative costs.

The Banding Offices will not require NABC certification of

new or existing banders but will recommend certification and

refer prospective banders to NABC. They will recognize certi-

fication as evidence of qualifications for a federal banding permit.

However, a proposal justifying banding will continue to be

required (i.e., NABC certification alone will not entitle one to a

federal bird banding permit).

7.3. NABC Certification

NABC has developed a certification program to recognize

standards of knowledge, experience, and skills. The sole purpose

of evaluating a bander trainee is to determine if he or she can

complete safely, efficiently, and accurately all tasks required of

the bander permit for which he or she is applying. The evalua-

tion will be thorough, including all aspects of bird capture,

handling, identification, ageing, sexing, banding, measuring, data

recording, and report filing. While the information in this manual

is considered basic to all applicants for certification and will be

tested in a written examination, evaluation of applicants' field

skills will emphasize techniques and procedures relevant to the

particular group or groups of birds for which the trainee is

seeking a permit. Separate evaluations of field skills will be

available for passerines, shorebirds, raptors, waterfowl, hum-

mingbirds, and seabirds.

Evaluations are based on both a written test and hands-on

demonstration of banding skills. NABC recognizes that both

portions of the evaluation are important and, indeed, complemen-

tary. Central to the certification process is the evaluation of a

trainee's ability to: use nets and traps properly, efficiently, and

responsibly; remove birds from them; and handle, measure, and

examine birds. A trainee without a basic understanding of bird

anatomy and banding techniques, or one who lacks the dexterity

and temperament for handling birds, may endanger the birds.

The written evaluation includes two parts: questions covering

basic knowledge of birds and banding, and problem-oriented

short answer questions.

The NABC recognizes the need for and provides certification

at three levels:

Assistant.—At the Assistant level, a trainee has achieved a

level of competence in removing birds from nets, bird handling

skills, and banding birds under the direct supervision of a bander

who is a Bander or Trainer. This level of certification is provided

to recognize the important contributions of those who assist with

the handling of birds at banding stations, but who do not wish

to take on the major responsibilities associated with record

keeping, and to provide a pool of trained individuals to assist

banders.

Bander.—The Bander level recognizes that a trainee has

achieved a level of competence in removing birds from nets,

identifying, sexing and ageing them, handling and banding them,

taking appropriate measurements, and keeping appropriate

records. The Canadian and U.S. Banding Offices issue two levels

of permits, the Subpermit and Master (Individual or Station)

Permit. NABC recognizes that both Subpermittees and Mas-

ter/Station Banders need the same level of knowledge and skill

and therefore provides only this one level of certification for

both—the Bander level of certification.

Trainer.—The Trainer level recognizes Banders who (1) have

demonstrated considerable banding experience, (2) have the basic

knowledge and skills associated with the Bander level of

certification, and (3) have demonstrated teaching skills such that

he or she can teach and evaluate proficiency in the basic

knowledge and skills associated with all levels of certification.

An applicant at the Assistant level must be certified by a

Bander or a Trainer. Applicants at the Bander level must be

certified by a Trainer. Applicants at the Trainer level must be

certified by two Trainers. Each successful candidate for certifi-

cation will receive a certificate signed by the Chair of the NABC

and the Bander or Trainer(s) who conducted the evaluation.

Certification is subject to periodic review by the NABC. Issuance

of banding Subpermits and Master/Station Permits is the

responsibility of the Canadian and U.S. Banding Offices. The

Banding Offices do not require NABC certification of new

banders or current Permit holders, but they do recommend

certification and refer prospective banders to NABC. They

recognize certification as evidence of qualifications for a federal

banding permit. However, a proposal justifying banding con-

tinues to be required. The NABC anticipates that its Trainers

will be involved in short courses for bander trainees.

As a result of NABC certification, bird studies will benefit

from an increased number of competent banders, more skilled

banders, more reliable data, and more opportunities for collabora-

tive studies. Birds will benefit from a safer, more effective North

American Bird Banding Program.

North American Banding Council Banders' Study Guide 9

8. HANDLING BIRDS

The proper way to handle a bird is the safest way. To ensure

the bird's safety during handling, it is crucial to use appropriate

grips, as described below.

Many birds are capable of inflicting a little pain or discomfort

on the bander; some, such as raptors and herons, may even draw

blood with their talons or threaten eye injury with their long

necks and beaks. Others will defecate on you, and some will bite

or scratch, but it is all part of the banding process. In any case,

never take any of your frustrations out on the bird. Consider the

hand that holds the bird to be separate from your body; learn not

to flinch when a grosbeak or hawk clamps its jaws down tightly

on your finger or when a flicker defecates in your face while you

are checking its fat condition. Laughter is often the best medi-

cine.

Right-handed banders normally hold birds in their left hand,

leaving their right hand free to scribe, hold banding pliers, and

so on. Left-handed banders do the opposite. No matter which

hand is chosen, you should feel comfortable transferring birds

from one hand to the other, which is part of the banding routine.

Never overlap the wings across the back of the bird or bring

the wings forward below the line of the body; this can cause

wing-strain and result in tissue damage. Always be careful that

the bird's body is not held too firmly. Excessive pressure placed

on the neck or body could result in broken ribs, damaged air

sacs, or suffocation. Breeding females carrying eggs could suffer

internal injuries if the abdomen is pressed. You should always

check for any signs of panting or other stress (see Section 13).

A good handler quickly learns to balance a secure, firm hold with

a gentle, noninjurious touch.

If a bird struggles loose from your grip, it is much better just

to let it go rather than to grab for it. What you usually get is a

handful of tail feathers, and you risk injuring the bird by a sudden

grasp.

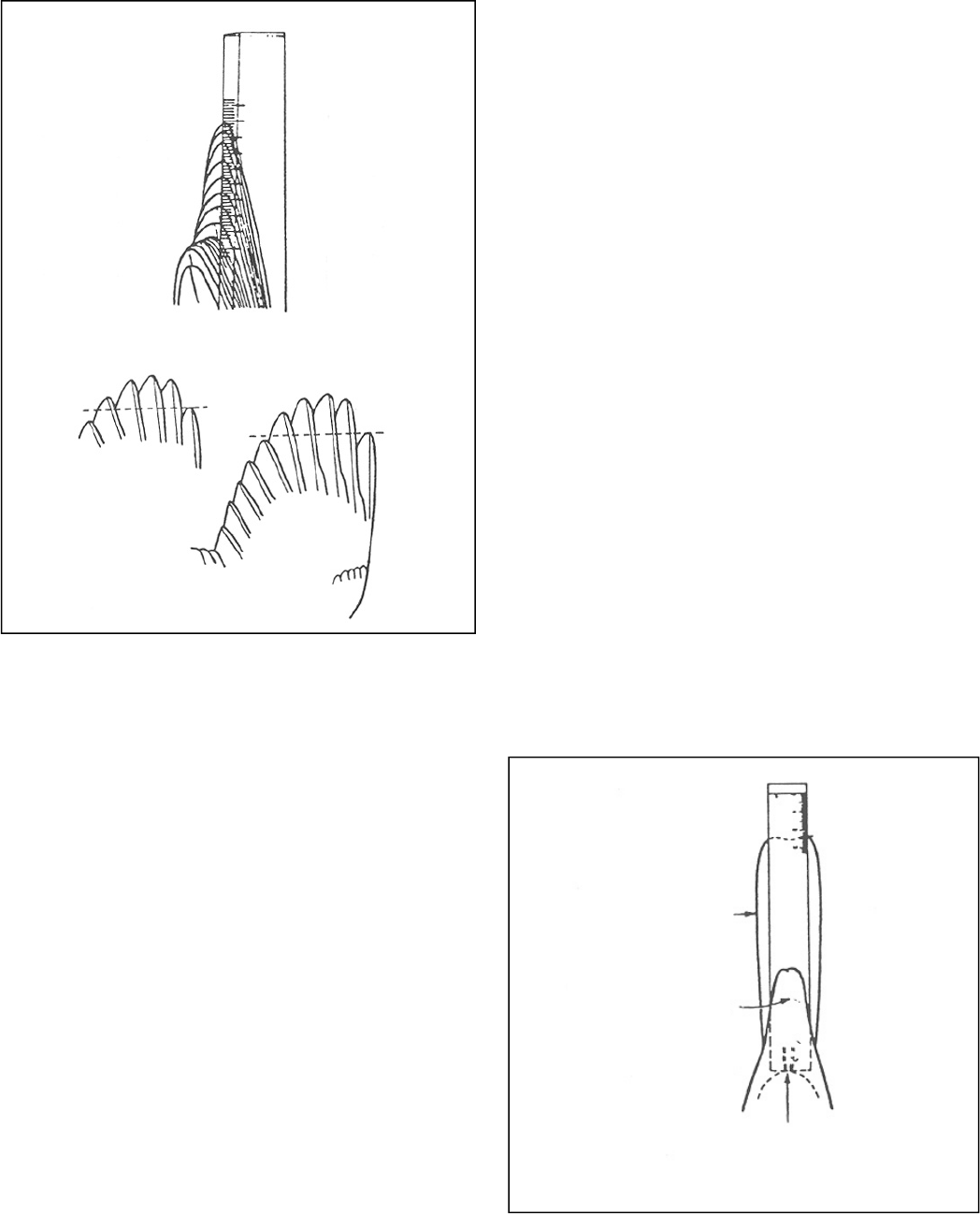

8.1. The Bander's Grip

The "Bander's Grip" (Fig. 1) is the best and safest way to hold

a small or medium-sized bird. Hold the bird with its neck near

the base of the gap between your forefinger and middle finger.

With these two fingers closed gently around the bird's neck, the

wings can be contained against the palm of your hand. The

remaining fingers and thumb are closed loosely around the bird's

body, forming a kind of "cage." This hold leaves the bird's legs

free for banding.

By pinching the tarsus at the metatarsal joint (heel), or

slightly foot-side of the joint if leg length allows, securely

between thumb and forefinger of the hand holding the bird, the

leg is secure enough that, should the bird struggle during

banding, the hold will prevent any injury to the leg. It is

important that the heel not flex while applying the band. You

can measure the wing chord or check for fat safely simply by

lifting your thumb away from the bird's body.

The key to the Bander's Grip is to hold the neck firmly

Figure 1. Aspects of the Bander's Grip showing how the tarsal (heel) joint can be held (from Lowe 1989).

10 North American Banding Council Banders' Study Guide

enough that the bird cannot pull its head back through your

fingers, but not so firmly as to risk harm or stress. Your hand

should cradle the body and restrain the bird from struggling so

that it is not injured or expending energy trying to escape. If the

bird struggles a great deal and you are finished applying the band,

except with shorebirds (see below), the legs can be folded and

placed between the bird's body and your ring finger as if the bird

were perched. This will minimize struggling and allows you to

proceed with other measurements.

Although this is the most basic of all banding grips, there are

some things you should know about holding certain species:

(1) Most birds are usually docile, but some (e.g., sparrows,

starlings, woodpeckers, blackbirds, grosbeaks, and jays)

often kick or bite. Some species (e.g., Song Sparrow) lie

calmly, then suddenly kick strongly in an attempt to free

themselves from your hand. Be prepared by keeping a firm

grip on the neck throughout. Kicking can be minimized

by positioning the leg not being banded between your ring

finger and the body of the bird as described above. Before

or following application of the band, some species in the

hand are calmed by allowing then to grasp your ring or

small finger, as though they were perched within your grip.

Bad biters can be handed a small twig or a cotton roll to

bite, or their heads can be covered temporarily by a light

piece of cloth. They can also be restricted by keeping the

fingers straight. Usually, it is best just to endure the pain

and to learn to keep your fingers away from beaks.

(2) Small birds such as wrens are especially adept at wriggling

out of the Bander's Grip. They use their feet to put pressure

on the fingers around their necks and quickly slip their

heads from your grasp. Again, your grip must be sure but

not stifling.

(3) Caution is required when handling hummingbirds. Al-

though they are tough birds for their size, they can go into

shock due to stress or lack of food. In addition to the

Bander's Grip, they can be held with the finger-tip hold,

which allows the greatest control of the bird while assuring

its safety: thumb on one side of the bird's body, second

(middle) finger on the other side of the body, and the

forefinger on top of the bird. By holding the first and

second fingers in a firm but relaxed grip, you will not

endanger the bird nor will you let it loose. Never hold a

hummingbird by its legs as this will cause injury.

(4) Use care when handling long-legged shorebirds, cranes, and

herons. Leave their legs free for banding and never fold

them up against their body (see Section 13.4). Restricting

the legs causes stress to the bird and may result in the

temporary loss of muscular control of the legs.

(5) When holding small raptors in the Bander's Grip, be very

certain that your grip is sure and that the talons are under

complete control. Raptors will grasp tightly their own feet

together and hold their legs in this position for some time.

Then they will lash out suddenly, sinking their talons into

the object nearest them.

(6) Some birds (e.g., woodpeckers, mimids, and icterids) are

apt to scream a lot. This does not mean they are in pain,

but it is certainly disturbing. Forget trying to calm scream-

ers. The best thing you can do is to cover their head with

a bird bag, process, and release them quickly.

8.2. The Reverse Grip

The "Reverse Grip" is a standard hold in some countries but

not widely used in North America. We recommend that you

master the standard Bander's Grip before trying the Reverse Grip.

In the Reverse Grip, the bird is held with the tail facing away

from you (Fig. 2). Your pinky and ring finger secure the neck

against your palm. Your thumb is placed gently but securely

across the lower abdomen, below the back and wing, or across

the rib cage. As in the Bander's Grip, the leg can be positioned

for banding by pinching the metatarsal joint between your thumb

and forefinger.

The Reverse Grip is not efficient if measurements are to be

taken because the bird must be rotated and held in the Bander's

Grip for most measurements. Processing is faster and incidents

of escape and injury when you stay with a single grip. The

Reverse Grip is useful, however, for banders with small hands

who must handle medium-sized birds (e.g., Common Grackles

and Mourning Doves) or when banding swallows and other birds

with extremely short tarsi. This grip puts the metatarsal joint

close to the thumb and forefinger. The Reverse Grip also can be

useful when you measure or study tail feathers.

8.3. The Photographer's Grip

Many passerines can be held safely by their legs for brief

periods, but you must grasp the legs as close to the body as

possible. Never hold hummingbirds, kingfishers, or goatsuckers

in this grip as their legs are too weak. Caution should be used

with holding large finches with this grip, since problems of wing

strain or fractured coracoids have been reported. Many banders

feel that this grip should never be used as a method of extracting

Figure 2. The Reverse Grip (revised from Svensson 1992).

North American Banding Council Banders' Study Guide 11

birds from nets.

The "Photographer's Grip" (Fig. 3) is used primarily to hold

birds while photographing them because it maximizes the amount

of plumage in view, briefly to transfer them from one bander to

another, or to examine certain features. For this hold, you

"scissor" grip the bird's legs, as near to the body as you can,

between the fore and middle fingers (or between the ring and

middle fingers if your hand is very small) and then pinch the

bird's tarsi between your thumb and fore- (or middle) finger.

Place index finger between the legs of large birds such as raptors.

In this hold, the bird is securely gripped above and below the heel

joint, which is bent into an "L" shape. The bird will be able to

flap its wings, but it should not be able to rock back and forth or

from side to side. Never hold a bird only by the lower part of its

legs; they will break! Place your free hand over the bird's back

to keep its wings from flapping until the photographer is ready

to shoot or the other bander is ready to take the bird in the

Bander's Grip.

Many birds, especially short-legged species, present

difficulties when the bander attempts to "scissor-grip" the upper

tarsus. In this case, you can pinch the bird's feet together between

the thumb and forefinger and pull the legs away from the body,

allowing you to use the middle and ring finger in a "scissor-grip"

higher up the leg. Once secure, the bander can release the feet

and reposition the thumb against the lower tarsus.

Birds should not be held in this grip for longer than

necessary because they will be using additional energy trying to

escape. Still, it is an essential grip to master because it can be

used while extracting birds from mist nets and to photograph

unusual captures for documentation.

8.4. Free Holds

Many waterfowl, raptors, herons, goatsuckers, and gulls are

simply too large to be easily held and banded by one person. In

addition, many large birds have dangerous talons and bills. In

these cases, handling is often done by one person while banding

is done by another.

Swans, geese, and larger ducks can be held on their backs in

your lap, between your inner thighs, between two hands, or under

your arm. The head and neck should always be under control and

point away from you so that the legs are free for banding. You

also will soon learn to point the cloaca away from you. Most

waterfowl are not aggressive, but geese may try to bite and they

have sharp claws. These are strong, slippery birds that will

escape easily if your hold is not secure. Some waterfowl banders

were taught to hold them by their wings, overlapped across the

birds' backs, but many banders believe that this may cause wing

strain. We do not recommend it.

Herons and gulls can be held on the lap or between two hands

as described above; to guard against their sharp bills, a cloth bag

can be placed over their heads. The person holding the bird must

keep the head and neck under control. Herons, loons, grebes, and

others will strike with their bill at your eyes.

Approach raptors in a trap or net from behind. Try to distract

them with one hand until their talons can be safely controlled.

Place them in a secure grip immediately after extraction, covering

the head so they can not bite.

Great care is needed to handle powerful birds of prey the size

of Cooper's Hawks and larger. For birds larger than a Red-tailed

Hawk, we advise having two banders on hand. If only one is

available, a large raptor may be held under your arm or on your

lap with a cloth bag over its head and your hand clenched firmly

around its legs.

8.5. Opening a Bird's Bill

Skill in opening a bird's bill reliably and safely is necessary

for situations such as extracting a tangled tongue or examining

mouth tissue (e.g., for injury or color indicating age or sex). A

bander should be prepared for any size and type of bird, which

will dictate the approach taken. With smaller birds, especially

those controlled using the Bander's Grip, the bill can be opened

with just one hand.

The bander's fingernails are used to pry open bills, so

maintaining some fingernail length is useful. Do not use foreign

objects for prying open the mandibles. A bird can often be

tricked into opening its bill by offering a finger or small stick or

twig to bite. Special care should be given to species with

sensitive Herbst corpuscles at the mandibles, such as ducks and

some shorebirds.

The mandibles should not be opened wider than needed to

accomplish the task. For smaller birds, one person can accomp-

lish this while controlling the bird. With the bird's body under

control in the Bander's Grip, the thumb and index or middle

fingernails of the bander's free hand are pried between the upper

and lower mandibles. As the mandibles are parted, place more

of the thumb and other finger(s) into the mouth and leave in place

as stops. The mouth can then be easily examined. Two people

may be needed to safely control larger birds (see Section 14.1),

which will free two hands for opening the bill. Use the nails of

Figure 3. The Photographer's Grip.

12 North American Banding Council Banders' Study Guide

both thumbs to pry apart the upper and lower mandibles. As the

mandibles are parted, place more fingers between them toward

the commissures (corners of the mouth) and leave in place as

stops. For larger or stronger birds and any whose bill is not easily

opened, hold the head by placing fingers behind the jaw and

gently extend the neck up and forward, then open the bill as

described above.

8.6. Carrying Devices

Banders often catch many birds at once. Because working

near the traps typically prevents other birds from getting caught,

banders of landbirds usually gather the birds up in bags or boxes

and carry them back to a central banding station. This procedure

also allows the birds to settle down and permits the bander to

carry many birds at once. Raptor banders use cans of several

sizes to hold raptors for banding and carrying (as do some

hummingbird banders). The tubes fit snugly over the hawk and

prevent struggling and possible injury. Tubes can be as simple

as two small cans taped together with holes punched in one end

from the inside out to prevent injury. Each species and sex may

require a different can size. Not all birds can be safely held in

carrying bags or boxes, but suitable carrying devices should be

available for whatever type of bird is being banded.

Once all of your carrying devices are filled, always release

any additional birds that have been captured (see double-bagging

below). Release them immediately at the trap or net site.

Remember, bird welfare always takes precedence. On those odd

occasions when you get caught without a carrying device, you can

naturally carry the bird in your hand, perhaps under your shirt

to minimize stress. Avoid carrying birds in shirt or pants

pockets.

8.6.1. Bird bags

Draw-string bird bags are ideally made of thin, soft cotton

(e.g., old sheets and pillow cases) and measure about 15 x 20 cm

or larger, depending on the size of the bird. The bags must be

large enough that you can reach in and extract the bird in the

Bander's Grip. If the whole body and tail of the bird can fit easily

in the closed bag, it is the proper size. It is a good idea to have

an assortment of sizes on hand. Draw-strings must be long

enough that they can be hung on a carrying device and hitched

shut to prevent the bird's escape. If a bag is too small for the bird,

feathers could break or bend, or the wings could be strained from

being held in an awkward position. The seams of the bags must

be finished with no loose threads (e.g., by French stitching).

Otherwise, the bags should be turned inside out to prevent birds'

claws from becoming entangled. Finally, bags of different colors

or prints help you to recall quickly which bird is in which bag,

but do not use very bright colors, which can frighten birds. Avoid

making bags with camouflage-colored material because, if

dropped, they may be difficult to find. Avoid dark-colored bags

when banding in warm temperatures.

Some banders find mesh (zippered) "lingerie" bags to be

superior to muslin because you can see what is in the bag. Birds

can see out of these bags, however, and could be more frightened

by movement during transport and activities at the banding

station. Hummingbirds can be banded and measured without

removing them from the bag. Mesh bags also are cooler and dry

quickly when washed.

When putting a bird into a bag, place your entire hand into

the bag, closing your other hand around the neck of the bag and

the lower arm and wrist of the hand that is holding the bird.

Then gently release the bird at the bottom of the bag and slide

your hand out of the bag, assuring that the bird stays in the

bottom of the bag. Pull the drawstring of the bag shut before

removing your hand from the neck of the bag. With the bird

safely at the bottom of the bag, grasp the neck of the bag and loop

it into a simple overhand knot to prevent its coming open. Take

care that the tail of larger birds is not tied into the closure.

If all cloth bags are in use, it is permissible to carry birds

temporarily in small, brown, paper bags, twisted at the top. They

are not "breathable," however, can't be hung up, and disintegrate

if they get wet, so they are not recommended for regular use. Do

not use plastic bags for this purpose because they prevent

circulation of air.

Never set bags holding birds on the ground (where they can

"hop" away or be stepped upon), in the shelf of a mist net (where

they could place excessive tension on parts of the net and injure

other birds), or hang them in a place where they can be forgotten.

Instead, hang bags on clothes pins (that can have trap or net

numbers on them) on your shirt, on the eye cups of your

binoculars if large enough, or fashion a wire hook to wear around

your neck, wear a necklace made from shower hooks, or simply

keep bags looped safely around your wrists. Special posts for

hanging bags can be installed at convenient spots near traps or

nets, but be sure not to forget bags there.

In some cases, a rush of birds expends the number of bags

available. Under these circumstances, place no more than two

birds of the same species in a single bag, provided space is

ample. One definite exception to this is that you always should

single-bag large or aggressive birds. Jays, grosbeaks, grackles,

chickadees, vireos, hummingbirds, woodpeckers, and raptors

should never be double-bagged, whereas warblers, kinglets, and

nonaggressive sparrows can be double-bagged. Adults may be

more aggressive than normal during the breeding season and

should also be kept separate. Always be sure that the bander is

informed of all bags containing more than one bird, so that they

can be processed first or rebagged separately as soon as possible.

Launder bird bags frequently, as they must be kept clean.

Dirty bags are unsanitary and unsightly. They may also harbor

diseases and parasites and reduce air circulation. Never use wet

bags; they might prevent air circulation or chill the bird inside.

Turn bags inside out and shake out debris. Loosely fill a net

washing bag with bird bags and wash on the gentle cycle in hot

water with a small amount of detergent and chlorine bleach.

Rinse thoroughly, then leave bags inside the washing bag for

drying. After drying, reverse the bags so that the raw edge of the

seams are on the outside.

If a diseased bird is caught, it is extremely important to put

that bag aside until it has been washed and disinfected. Also,

take the time to wash and disinfect your hands before handling

other birds. Moist towelettes in your field kit make good

antiseptic cleaners. Small bottles of antiseptic lotion also are

North American Banding Council Banders' Study Guide 13

available.

8.6.2. Carrying boxes

Small carrying boxes, usually with two to several compart-

ments, are sometimes used to store birds prior to banding (Fig.