Mist-netting

with the public

A guide for communicating

science through bird banding

Melissa Pitkin

Mist-netting with the public

A guide for communicating science

through bird banding

Melissa Pitkin

PRBO Conservation Science

Klamath Bird Observatory

In cooperation with the

North American Banding Council

Acknowledgements

Funding provided by:

PRBO Conservation Science

Klamath Bird Observatory

Rogue Valley Audubon Society

Special thanks to all reviewers:

Geoff Geupel, Diana Humple, Sue Abbott, PRBO Conservation Science,

John Alexander and Ashley Dayer, Klamath Bird Observatory,

CJ Ralph, Redwood Sciences Laboratory,

Doug Wachob, Teton Science School,

Shelley Morrell, Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory

North American Banding Council Publications Committee

And to all the organizations who participated in the survey!

Table of Contents

Introduction

1

Pre-visit Planning

5

Staff Hiring and Training Guidelines 1

1

Bird and Human Safety 1

2

Preserving Data Quality 1

6

Developing Interpretive Tools 1

7

Publicizing Your Opportunity 1

8

Conducting a Visit 2

0

Program Evaluation 2

4

Toolbox 2

5

Other Useful Information 3

7

References 3

8

1

The disconnect between humans and the natural world has been cited as a factor contribut-

ing to declining wildlife populations and the destruction of habitat. People are disconnected with

the natural world in part because they lack

understanding of and connection to science

and scientists. The National Science Board

(2002) reported that 70% of Americans do

not have a basic understanding of the sci-

entic process. Furthermore, public percep-

tion and understanding of scientists is poor;

studies have shown that children and adults

typically picture scientists as middle-aged

white men who wear lab coats, glasses, and

Einstein-like hair styles and work in labo-

ratories lled with test tubes and bubbling

potions (Mead and Metraux, 1957, Mirsky

1997).

In a recent paper, Nalini Nadkarni (2004) proposed the idea of scientists as “ambassadors of

conservation” who can reach out to a variety of audiences and connect people with their natural

world. Due to the passion and knowledge of their research, scientists are able to relate their

science to the lives of the “scientically unaware” (Nadkarni, 2004). To bridge the gap in under-

standing of science, scientists, and the natural world, scientists can incorporate public education

programs into their research.

Effective education programs are those that provide participants with direct experience in the

subject matter (Trombulak 2004). Inviting the public of all ages to observe, take part in, interact

with, and learn from scientists gives participants direct experience with research and builds under-

standing of the scientic process. The capture of birds in mist nets presents a unique opportunity

to demonstrate science-in-action to a wide variety of audiences while at the same time generating

valuable scientic information on bird populations.

Scientists involved in mist-netting programs are often hesitant to engage the public in their

work due to numerous challenges associated with collecting data on wildlife under the public’s

eye. However, interest in combining educational programs with bird research programs is growing

among ornithologists through the recognition that such programs increase awareness of birds and

bird conservation issues, increase potential for funding and support of research, and improve the

communication of results to land management partners (Riparian Habitat Joint Venture, 2004).

Bird Conservation Plans also encourage those conducting research on bird populations to engage

in public education programs. In the March 2005 Memorandum to All Banders, the Bird Banding

Laboratory of the US Geological Service recognized the importance of teaching through banding

Introduction

2

and has begun issuing educational banding permits for stations whose sole purpose is education.

These permits are issued to North American Bird Banding Council certied banders who are the

“best possible ambassadors” for bird banding (BBL, 2005).

As a result of the growing interest in linking education programs with research, biologists and

informal educators at various bird observatories and non-prots in the Americas have requested

help in designing and implementing such programs. To answer this request, I have created this

manual with two goals: to connect the public with science, scientists, and conservation and to

improve the quality and quantity of education programs delivered in conjunction with bird research

that uses mist nets. The guidelines contained in this manual are based on feedback through sur-

veys from 25 organizations (Table 1, page 4) in North America, as well as nine years of profession-

al experience conducting education programs with mist-netting at PRBO Conservation Science and

the Klamath Bird Observatory. The goal of the survey was to establish a need for this of manual

and gather information on how the organizations conducted mist-netting education programs.

Twenty-one of 25 respondents answered that this type of a manual would be useful. The re-

maining questions enabled me to identify the challenges of incorporating education programs with

mist-netting and present ways to address these challenges. Challenges include; volume of birds

caught, number of staff, site accessibility, funding, and stress to birds. Solutions and strategies

for safely and effectively involving the public in mist-netting demonstrations include conducting

extensive pre-visit planning, implementing staff hiring and training guidelines, developing a plan for

bird and human safety, using interpretive tools, publicizing your opportunity, and evaluating your

programs. It is my hope that this manual will achieve its goals of bridging the gap between science

and the public while facilitating the delivery of education programs with mist-netting research.

History of Bird Banding

In 1595, one of King Henry IV’s banded Peregrine Falcons disappeared in France, chasing a

bustard. It turned up about 1350 miles away in Malta, an island in the Mediterranean south of

Sicily, 24 hours later, and averaging 56 miles an hour! With this discovery, the fascination with un-

derstanding bird migration was born. Questions including where do birds go, how long do they live,

how do nestlings know where to disperse (to name a few) were formulated and tested in the spirit

of scientic inquiry. In 1899, a Danish school teacher, Hans Mortensen, developed the system of

putting aluminum rings on the legs of pintail, teal, hawks, starlings, and storks. On the bands he

included his name and address in the hopes they would be returned if found. This system was

formalized in the United States in 1909 with the formation of the North American Bird Banding

Council (NABBC) (www.pwrc.usgs.gov/BBL/homepage/history.htm).

Current Status in North America

Today, there are many organizations and individuals who band birds in North America. Table

one contains a list of 45 bird observatories and organizations that band birds. This table is not

Introduction

3

inclusive of all organizations and individuals. There are many more, including biologists working

for state and federal agencies and individuals permitted to band birds independently. In addition,

many groups partner with biologists in Central and South America. Each year approximately 1.1

million birds are banded in North America. As of 2005, a total of 57 million birds had been banded

(www.pwrc.usgs.gov/bbl/default.htm). With non-government organizations, agencies, and individu-

als studying birds throughout the Americas, this presents an excellent opportunity to teach people

about birds, research and conservation, and the scientic process. Many groups are already utiliz-

ing this opportunity and currently implement education programs in conjunction with mist-netting.

Each year, at least 47,000 people participate in mist-netting demonstrations (Pitkin 2005).

To use this manual, you must rst be able to answer the question Why invite the public to my

mist-netting station? Whether you work within an education or research organization, involving the

public in mist-netting demonstrations presents several benets. Most importantly it is an oppor-

tunity to bridge the gap between scientists and the public. Connecting people with birds through

in-the-hand observation also helps build appreciation and understanding of birds among partici-

pants. Educators and researchers who observe this appreciation among visitors recount stories of

amazement and wonder as people discover the diversity of bird species surrounding them. From a

marketing point of view, it is a chance to raise funds, build organization memberships, and recruit

volunteers due to the potential to reach large numbers of people each year. Based on survey feed-

back, the annual number of visitors to mist-netting stations ranged from 30 to 15,000 people with

an average of 1,900 people reached annually. Every mist-netting demonstration presents educa-

tional, scientic, and organizational benets.

Common Fears and Challenges

Despite numerous benets, many fears and challenges exist when inviting the public to a

research site. Common challenges

include: adequate staff, funding, high

capture rates, site accessibility, space

needed to accommodate groups, and

the ability to convey educational mes-

sages. Survey respondents were asked

to list the challenges they face (Figure

1). Challenges listed in the ‘other’ cat-

egory include low capture rates, public

perception, stress to birds, and preser-

vation of data quality. All documented

challenges are addressed in this manual

with specic recommendations for addressing them.

Introduction

4

Introduction

Table 1. A Selection of Bird Observatories/Research Organizations in North America

* Indicates organizations which participated in the survey

Organization Name

Alaska Bird Observatory (Alaska)*

Atlantic Bird Observatory(Nova Scotia)*

Bainbridge Island Bird Observatory (Washington)

Beaverhill Bird Observatory (Alberta)*

Black Swamp Bird Observatory (Ohio)*

Braddock Bay Bird Observatory (New York)

Bruce Peninsula Bird Observatory (Ontario)*

Cape May Bird Observatory (New Jersey)

Big Sur Ornithology Lab/Ventanna Wilderness Society (California)*

Chipper Woods Bird Observatory (Indiana)*

Coastal Virginia Wildlife Observatory (Virginia)*

Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology (New York)

Deep Portage Bay Learning Center (Wisconsin)*

Derby Hill Bird Observatory (New York)

Fundy Bird Observatory (New Brunswick)*

Golden Gate Raptor Observatory (California)

Great Basin Bird Observatory (Nevada)

Gulf Coast Bird Observatory (Texas)

Holiday Beach Migration Observatory (Ontario)

Hornsby Bend Bird Observatory (Texas)

Humboldt Bay Bird Observatory (California)*

Institute For Bird Populations (California)*

Idaho Bird Observatory (Idaho)*

Innis Point Bird Observatory (Ontario)

Institute For Outdoor Education and Environmental Studies (Ontario)*

Klamath Bird Observatory (Oregon)*

Lesser Slave Lake Bird Observatory (Alberta)

Long Point Bird Observatory (Ontario)*

Manitoba/Delta Marsh Bird Observatory (Manitoba)

Manomet Center for Conservation Sciences (Massachusetts)

Ohio Bird Banding Association (Ohio)*

Old Myakka Bird Observatory (Florida)

Powdermill Bird Banding (Pennsylvania)

PRBO Conservation Science (California)*

Prince Edwards Point Bird Observatory (Ontario)*

Rio Grande Valley Bird Observatory (Texas)

Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory (Colorado)*

Rocky Point Bird Observatory (British Columbia)*

Rouge River Bird Observatory (Michigan)*

Southeast Arizona Bird Observatory (Arizona)

San Francisco Bay Bird Observatory (California)*

Starr Ranch Audubon Sanctuary (California)*

Sutton Avian Research Center (Okalahoma)*

Toronto Bird Observatory (Toronto)

Whitesh Point Bird Observatory (Michigan)

5

Prepare your site

It is important to consider your site when planning educational programs at mist-netting sta-

tions. Whether you are working at a permanent banding station with a facility or at eld sites

without facilities, you must have a plan for access, parking, safety, and interpretation.

Vehicle Access

Access is critical and applies to accessibility by vehicles as well as by people on-site. Stations

located over an hour drive from major cities and towns may have a harder time securing partici-

pants, especially from the K-12 community who are conned by school hours. Nearby camping or

other overnight accommodation may make accessing the site for school groups easier. In addi-

tion, more remote sites may offer multiple experiences for groups traveling long distances. If you

are at a location farther from a city center, think about partnering with organizations or naturalists

who may want to collaborate in offering multi-disciplinary eld experiences as part of their existing

programs. Once at the site, visitors will need ample parking. Larger groups may come on a bus

or in multiple cars. Be sure to have adequate parking and bus turnaround. If parking is a prob-

lem, you may want to limit group size and number of vehicles or arrange a shuttle to and from a

nearby parking area.

Human Access

On-site access to trails, mist nets, or interpretive sites

must also be considered. Trails must be maintained, free

of poison oak or ivy, nettle, thistle, downed trees or logs,

and large holes. Tall grasses and other vegetation should

be pointed out to visitors as possible sources of ticks or

chiggers. Trail maintenance will need to be done through-

out the year or season, especially in areas with vigorous

plant growth. Be sure to plan time for staff, volunteers, or

interns to maintain trails. Trails that encounter hazards

such as steep or rocky slopes, creek crossings without a

bridge, standing water, deep mud, or wet vegetation should be avoided, as they may be unsafe or

uncomfortable for visitors, taking away from the educational experience. Also consider accessi-

bility by handicapped people. The trail itself may be inappropriate for visitors in wheelchairs, but

perhaps your banding site can be modied to accommodate wheelchairs. Blind visitors may also

be unable to traverse difcult trails but can still participate in the experience by listening to bird

sounds, handling study skins, touching tools and equipment, and listening to interpretation.

Interpretation Area

Designating an area for interpretation, or a speaking point, is a critical component of site

preparation. Due to the nature of mist-netting sites, open areas may be limited. Limit your group

size if you cannot accommodate large groups. It is important to address the entire group upon ar-

Pre-visit Planning

6

rival: introduce them to the experience, and outline how the program will be structured. Maintain

the interpretation area free of hazards as outlined above, to allow room for sitting or standing. At

sites with a permanent facility, such as at PRBO’s Palomarin Field Station, an interpretive deck

was built to accommodate groups. This created seating opportunities that were dry and comfort-

able for a wide variety of ages of visitors.

Conveying the Message

It is critical that you determine the messages you wish to convey before you begin your mist-

netting demonstrations. As with any educational program it is important to know your audience

and tailor your message to your audience’s age, background, and learning ability. Participants in

mist-netting programs come from a variety of audiences including K-12 students, college stu-

dents, community members, scientists, and habitat managers. Community members can include

the public, Audubon groups, scout groups, naturalist groups, Elderhostel groups, and birding

groups. From the survey participants, K-12 students were the audience type that most commonly

participates in these types of programs.

Survey respondents listed the following as key messages they communicate through

demonstrations:

• Value of long-term monitoring*

• The scientic process*

• Linking science and conservation*

• Appreciation for birds*

• Migration*

• Bird diversity and adaptations

• Bird population dynamics

• Birds as indicators

• Habitat loss or change

• Careers in wildlife biology

Items with * were listed by 20 or more out of 25 respondents. These messages are elaborated

below with key points to consider when conveying these messages.

Long-term Monitoring

Long-term monitoring of bird populations is often the motivation for mist-netting birds. Moni-

toring is the continuous scientic study of an organism or population with the goal of detecting

changes over time. Because these changes often take years to detect, monitoring is a com-

ponent of science that is not often emphasized when studies that provide quick and interest-

ing answers can be used instead. It is critical to stress the importance of long-term monitoring

programs for understanding population changes in birds and other wildlife. The National Science

Foundation states that long-term research is important because: changes occur slowly; effects

of rare events can only be evaluated when ongoing studies have been conducted; ecological

Pre-visit Planning

7

processes vary from year to year and can only be understood from a long-term view; and long-

term studies allow us to interpret short-term studies (NSF, 2004). Because mist-netting stations

exemplify long-term research and monitoring of bird populations, they provide biologists with an

excellent opportunity to teach people about this component of science. The toolbox on page 25

contains a hands-on graphing activity where students investigate changes in population size and

discuss the value of long-term studies. The activity was created by PRBO using Warbling Vireo

data but can easily be adapted to your site.

Scientic Process, Science and Conservation, Scientic Research

To bridge the gap between scientists and the general public, mist-netting demonstrations

should strive to communicate the scientic process, the value of scientic research, and the link

between science and conservation. The scientic process can be summarized as a ve-step

process:

Identify a problem or question that is driving your scientic investigation.

Develop a hypothesis proposing the answer to the question or problem. A hypothesis must

be testable.

Test the hypothesis.

Evaluate the data. Once you have nished

testing your hypothesis, determine if the

data collected support the hypothesis

Do your results cause you to ask further

questions?

Every mist-netting station should be able to

list the goals and specic questions being asked

through the research and monitoring (Ralph

et al., 1993). With mist-netting, the problem

or question may have to do with declining bird

populations, changing habitats, changing species composition in an area, timing of migration,

bird species diversity, survivorship in birds, bird response to restoration, etc. There are numer-

ous questions that can be answered by studying birds using mist nets. It is important to address

the questions central to your research and monitoring, and explain why you are mist-netting birds

within the framework of the scientic process.

How your organization utilizes data you collect is an important question to answer to visitors.

Talk about the land managers and scientists your organization partners with. Share examples of

how ndings have been used to modify or inform management decisions or answer conservation

related questions. This is a good opportunity to talk about Bird Conservation Plans and Partners

In Flight.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Pre-visit Planning

8

Appreciation for birds

A fascination with and appreciation for birds is also fostered during mist-netting demonstra-

tions. Twenty-four of 25 participants selected appreciation for birds as a focus of their educational

programs. The live bird in the hand is the hook or draw that gets people interested. Visitors of all

ages are in awe of the brightly colored warbler or the sparrow resting calmly in your hand. Holding

a live bird in your hand presents an easy and effective way to demonstrate relationships between

natural history and adaptations including: bill shape and prey type, wing length and migratory or

resident status, rictal bristles and ycatching, large eyes and low light conditions, etc.

Migration

Migration remains in part a mystery to scientists and the average person. Twenty-three out of

25 respondents said it was a key theme in their banding demonstrations. Knowing wintering and

breeding ranges and distances traveled for commonly caught species and presenting that informa-

tion during demonstrations is an excellent way to inspire people about bird migration. Studying bird

migration also helps us answer conservation questions such as ‘What are important stop-over hab-

itats that need to be protected?’ or ‘What are important bird migration routes?’ Survival estimates

of birds on wintering vs. breeding grounds can be used to help explain bird population declines.

Many researchers are now participating in DNA studies to determine migratory patterns of related

populations. All of these topics are interesting components of a banding demonstration.

An excellent way to teach people about migration is to join in the celebration of International

Migratory Bird Day (IMBD). Mist-netting demonstrations are an excellent addition to an IMBD cel-

ebration. If your organization bands birds, consider organizing an IMBD celebration, or partner with

your local Audubon group or environmental education center to create a celebration. Mist-netting

in a fair/festival situation is different than a scheduled group visit. Visitors may arrive constantly

throughout the morning, in a steady ow. This may put a strain on your staff and volunteers, es-

Pre-visit Planning

Partners In Flight and Bird Conservation Plans

Partners In Flight is an international coalition of land managers (public and pri-

vate), non-government organizations, researchers, individuals, and lawmakers working

together to reverse the decline of songbirds. To achieve this goal, Partners In Flight

has created local chapters and Bird Conservation Plans for specic states, regions, or

habitats. The goal of the Bird Conservation Plans is to prevent further habitat loss or

degradation resulting in the decline of focal bird species. Conservation Plans identify

focal bird species and associated habitat objectives important for maintaining stable

populations of these species. For more information visit www.pif.org.

9

pecially if your site receives a high volume of birds. Having guided trips to mist-netting posted at

scheduled times is one way to limit continuous trafc to the banding station. It is also important

to have additional staff on hand to accommodate visitors. Keep in mind that public perception of

mist-netting is critical, especially in a widely publicized community event.

Connection with scientists and science as a career

Though this was not emphasized by a majority of the organizations surveyed, it is a topic that

every banding demonstration should emphasize. Public perception of scientists is poor, and many

youth don’t consider being a scientist or biologist a career option. When you have a group at your

site, tell them how you became a biologist and have your staff and interns do the same. Inviting

the public to mist-netting demonstrations is an excellent way to broaden people’s view of scientists

and possibly open doors in a young person’s life.

Logistics of a visit

Your site and resources will determine many of the lo-

gistical concerns. Program length varies based on group

size and site accessibility. A typical visit will last just over

an hour with a maximum group size of 30 people. This

hour assumes visitors will tour the nets in addition to the

banding station. If groups will not be taken to check the

nets the visit may be shorter. The majority of organiza-

tions surveyed took people to at least some of the mist-

nets (18/25) and on average, 9 people at a time were

taken on a net run. The largest group size taken on a net

run was 20, however, I recommend that the number of

people touring the nets not exceed 15 (typically half a nor-

mal school class size). Sites with narrow, heavily vegetated trails lend themselves to smaller group

sizes. With groups approaching 30 people, splitting the group into two or more smaller groups (~15

students) is critical. To split groups, you must have enough staff and activities to simultaneously

occupy each group. With a split group, one half accompanies at least two banders to check the

nets and then observe the banding process. The other group is engaged listening to a talk, observ-

ing birds in the eld, examining study skins, watching a video, etc. Then the groups switch. Split-

ting the group will extend the length of a visit because both groups engage in the full program.

Mist-netting demonstrations are generally offered in the morning, as constant effort mist-netting

Pre-visit Planning

Dedicating one person to interpretation and group management is

critical to a successful mist-netting demonstration.

10

follows the protocol outlined in the Handbook of Field Methods for Monitoring Landbirds (Ralph et

al, 1993). Having groups arrive mid-morning is best for higher capture rates, as more birds tend

to be caught at this time . However, it is best to have groups arrive no earlier than after the rst

net run, allowing banders ample time to get organized. Realistically, most groups can’t arrive at a

site before 8:30 a.m., due to site location and limitations of the school day. The seasons and fre-

quency of programs offered depends upon the monitoring protocol. Stations following the Moni-

toring Avian Productivity and Survivorship (MAPS) protocol are operated once every 10 days, dur-

ing the breeding season only, and are thus limited in the number of groups that can be scheduled.

Stations that mist net birds daily and/or year round can schedule more group visits. Scheduling

visits in the winter is discouraged due to low capture rates and weather-related cancellations. In

my experience, scheduling more than 3 visits a week may also result in staff burnout.

Another consideration is whether to offer your programs free of charge or for a fee. Of the 25

survey respondents, 12 charge some sort of fee. Fees were charged either per person ($3-$5

each) or a at rate ($35-$125). Some groups ask for a donation of an unspecied amount. Con-

sider your costs and funding sources, and if you will create a sliding scale or fee waiver for groups

without sufcient funds.

Depending on the resources in your community, transportation costs for school groups may be

prohibitive. You may be able to secure grants from education groups to cover bus fees. Check

with your local school districts, Rotary clubs, local Audubon chapters, National Audubon Society

and other natural history or conservation organizations for eligibility and availability.

Pre-visit Planning

Summary of logistic considerations

• Visit length 1–1.5 hours,

• Maximum group size—30 people

• Maximum number of people checking nets—15

• Program start time-between 8:00—10:00 am

• Offer visits spring, summer and fall

• Fees optional- $3—$5 per person or $35—$125 per visit

11

Hiring Guidelines

It is absolutely critical that biologists who operate your mist nets are good with people and are

trained to talk with the public. Job, internship, and volunteer postings should list working with

the public as a component of the position. In addition, it is extremely helpful to have one person

dedicated to interpretation and managing the group, in addition to at least two people whose

primary duties are to band birds. The North American Banding Councils’ Banders Study Guide

recommends that at least two people, preferably three, are necessary when groups are visiting

(NABC, 2001, pg. 48-49). Twelve out of 25 organizations have a dedicated educator in addition to

banding staff when a group is visiting, and 15 out of 24 organizations felt it necessary or prefer-

able. Having enough people is key to keeping birds safe and maintaining a positive perception of

mist-netting.

Training Guidelines

It is critical to have well trained and prepared staff, volunteers, and interns. The North Ameri-

can Banding Council has produced three publications relevant to banding passerines:

•The North American Banders’ Study Guide (English and Spanish)

•The Instructors’ Guide to Training Passerine Bird Banders in North America (English and

Spanish)

•The North American Banders' Manual for Banding Passerines and Near-passerines (English

and Spanish)

Information on how to obtain these publications is available at www.nabanding.net/naband-

ing/pubs.html. Certication with the North American Banding Council is also recommended.

Conducting practice runs prior to a group visit will prepare your staff for the visit. In addition,

the outline for conducting a visit, pages 20-23, is a good training tool.

Visitors always want to know answers to a few key questions, such as ‘Why are you doing

this?’, ‘Who is your organization’, and ‘Where do you get your funding?’ These and other common-

ly asked questions and answers can be found in the toolbox, page 33. Distribute or go over these

with your crew. Make sure staff, interns, and volunteers can answer the big-picture questions

about bird conservation and your organization. It is also important to know how to answer ques-

tions about injuries to birds. For more on this topic, see the Bird and Human Safety section.

Staff Hiring and Training Guidelines

12

Human Safety

Human safety is an important consideration when you bring people to an outdoor setting. As

described in the pre-visit planning section, rough ter-

rain, creek crossings, and poisonous plants and animals

could jeopardize human safety. Prepare your site for

visitors, anticipate hazards, and be prepared with ap-

propriate rst-aid. For some groups, this may be the

rst time out of a city or urban area. Assess the condi-

tion of visitors before heading out on the net trail. If you

have a question about a person’s ability to navigate the

trail, describe the conditions and suggest they wait at the banding area for the rest of the group

to return. If no restrooms are available, let people know ahead of time so they can make other

arrangements.

Bird Safety

Bird safety should always be the number one priority after human safety. The North American

Banding Council has published the Bander’s Code of Ethics (see page 15) as a guide for safe

bird banding. In addition, the North American Banding Council’s North American Banders’ Study

Guide (NABC, 2001), addresses bird safety and injury prevention. All personnel should adhere to

the code of ethics when banding birds and be familiar with bird safety considerations. Even when

banders adhere to the code of ethics, situations may arise when a bird becomes injured or dies.

If this happens when the public is present, their support and perception of bird banding is at

stake. Therefore, it is important that banding presentations do everything possible to ensure that

visiting groups do not interfere with bird safety.

Preventing injury is done by following the code of ethics, minimizing the time birds spend in

nets and in hand, adhering to protocol, paying attention to weather conditions and the needs of

individual birds, and knowing which species are vulnerable to stress, wing strain, or other injuries.

When a group is visiting, it is important that these same guidelines are followed, despite the ad-

ditional distraction. Follow these steps to prevent harm to birds:

Attend to sensitive bird species rst and with the special attention they need.

Always have qualied, highly-trained banders handling and processing birds when groups

are visiting.

Have the materials on hand to deal with stressed or cold individuals, such as a “hospital

box” or other dark quiet container to put birds in until they are calm and warm enough to

y away.

Have sugar water on hand for hummingbirds and other rst-aid items such as medical

tape for splinting and styptic powder to stop bleeding.

For more on bird safety, please refer to the Mist-netter’s Bird Safety Handbook (Smith et

al., 1999) and the North American Banders’ Study Guide (NABC, 2001)

1.

2.

3.

4.

Bird and Human Safety

Human safety checklist

√ maintain trails

√ assess visitor abilities

√ warn about hazards

√ communicate bathroom options

when scheduling visits

13

System of communication

Banders should communicate with each other and education staff or volunteers about what

they need in order to focus on the needs of the bird at

all times. For example, difcult extractions from the

net may be easier without a group watching. A good

idea is to work out some phrases such as “Would you

mind taking the group on to the next net? This bird is

going to take a lot of concentration for me to untangle

it” or “Why don’t you move on with the group to see

what other birds we caught, and I'll focus on this bird?”

Avoid displaying injured or dead birds to the public. If

asked directly about injuries and death it is important to answer truthfully and calmly. Calculate

the injury rate for your site. It will likely be less than 1%. Knowing this will help you answer the

tough questions about bird mortality. The following are some scenarios and suggestions for han-

dling difcult situations with the public.

Scenario 1— Injured/dead bird at net

When checking nets, if you come across an injured or dead bird in a net, the bander who

discovers it rst should signal to the other bander to take the group on to another net while they

attend to this bird.

Scenario 2— Injured/dead bird at banding station

When bringing birds back to the banding area, banders should be aware of the condition of the

bird in the bag. If it is dead, don’t pull it out in front of the group; instead, move on to another bird

and discreetly alert other banders of the situation so they can attend to the needs of that bird

without the stress of people watching. If a bird shows signs of stress during processing, address

it by placing it in the hospital box and explaining to the group what you are doing.

Scenario 3— Bird won’t y away after processing

When a bird doesn’t y off after banding, the bird should be picked up and placed in the hos-

pital box if re-catching it won’t increase the birds stress. Let people know that the dark, warm,

quiet box will help birds calm down, enabling them to y away. At this point it is best to continue

processing another bird or move the group on to another activity. If possible, have one bander re-

lease the bird when it’s ready, out of the public’s eye. Once it ies off, the bander can report back

to the group if they are still present.

Scenario 4— Bird dies during processing

If a bird dies during processing in front of the group it is important to remain calm. Discuss

possible reasons for the death: hatch-year birds are generally not as healthy, extreme heat or

cold, prior injury, or unknown reasons. Talk about the mortality rate for your site, the precau-

Bird safety checklist

√ train staff in bird handling

protocols

√ monitor weather

√ pay attention to sensitive species

√ communicate with each other

√ have a hospital box, or equivalent

Bird and Human Safety

14

tions you take, and the symptoms you look for to prioritize bird safety. Compare the mortality

that results from mist-netting to that which may result from other causes. For example, survival

estimates of wintering birds suggest that as many as half of the young birds caught in the fall will

die of natural causes by the following spring. If you contribute dead birds to a study skin collec-

tion, mention that the bird becomes a valuable scientic specimen contributing to the knowledge

of the species.

Other considerations

Many people are concerned about the impact to the bird from the weight of the band and the

process of banding and measuring the bird. Explain that lightweight aluminum bands are negli-

gible: bands increase most birds weight by less than 0.5%. In comparison, many birds increase

their weight by 75-100% in preparation for migration. It is also good to point out that many healthy

birds are recaptured, year to year, day to day, and even within a day, showing that banded birds

are able to resume their lives after the brief banding process. Having examples of long-lived

banded individuals demonstrates that banded birds can survive many years with bands. Know

how long it takes you or your staff to process a bird, from start to nish (when a group is not visit-

ing) as a way to illustrate the minimal impact to the bird. Always emphasize that bird safety is

your rst priority. Finally, be able to talk about the benets of studying birds using mist nets.

Safe release techniques

Releasing the bird is often the favorite part of the program for visitors. Twenty of 25 organiza-

tions allow visitors to release the bird once it is banded. However, it is not always as simple as

opening your hand and watching it y away. If you band birds at a banding laboratory, be sure you

are releasing birds well away from the building, windows, and parked cars. Birds may turn back

when released and hit the window. It is also important to release birds close to the ground in an

open area to allow for quick and easy recapture of a bird that immediately lands on the ground

instead of ying off (NABC 2001, pg 26). Chasing a bird through shrubs or vegetation adds extra

stress to the bird. Always assess the birds condition before you hand it to someone to release.

If it looks stressed at all, release it yourself and away from visitors. A bird that does not y away

may leave the group feeling uneasy about the process of mist-netting. Finally, selecting one

student in a large group of kids to release a bird may cause unnecessary disappointment among

students.

Visitors often want to take photographs of birds prior to release. Photographs may increase

handling time and delay processing of birds waiting to be processed. Holding a bird in the pho-

tographer’s grip may also result in injury to the bird if it is agitated and apping its wings wildly.

It is OK to politely say no to visitors, explain why, and continue processing birds. However, if you

have the time and staff to allow this, it can be an advantageous experience. Some people have

speculated that the ash may be harmful or disorienting to birds. I have not found any evidence

to support or disprove this. Some organizations ask photographers to turn off the ash as a pre-

Bird and Human Safety

15

caution. Remember, people who want to touch and photograph birds are doing so because they

are amazed and excited about what they are seeing. When denying requests to touch and photo-

graph birds, always do so in a kind and respectful manner.

Banding in a facility

Banding inside a facility raises another bird safety issue. Birds that escape during process-

ing run the risk of hitting windows or walls or becoming difcult to re-capture. Be sure you have

a long handled net for capturing birds from the ceiling or other means for safely capturing birds

in an enclosed space. Opening doors and windows and asking the group to wait outside will help

minimize stress and injury to the bird.

Bird and Human Safety

The Bander’s Code of Ethics– North American Banding Council (NABC, 2001)

1. Banders are primarily responsible for the safety and welfare of the birds they study so that

stress and risks of injury or death are minimized.

Some basic rules:

• handle each bird carefully, gently, quietly, with respect, and in minimum time

• capture and process only as many birds as you can safely handle

• close traps or nets when predators are in the area

• do not band in inclement weather

• frequently assess the condition of traps and nets and repair them quickly

• properly train and supervise students

• check nets as frequently as conditions dictate

• check traps as often as recommended for each trap type

• properly close all traps and nets at the end of banding

• do not leave traps or nets set and untended

• use the correct band size and banding pliers for each bird

• treat any bird injuries humanely

2. Continually assess your own work to ensure that it is beyond reproach.

• reassess methods if an injury or mortality occurs

• ask for and accept constructive criticism from other banders

3. Offer honest and constructive assessment of the work of others to help maintain the highest

standards possible

• publish innovations in banding, capture, and handling techniques

• educate prospective banders and trainers

• report any mishandling of birds to the bander

• if no improvement occurs, le a report with the Banding Ofce

4. Ensure that your data are accurate and complete.

5. Obtain prior permission to band on private property and on public lands.

16

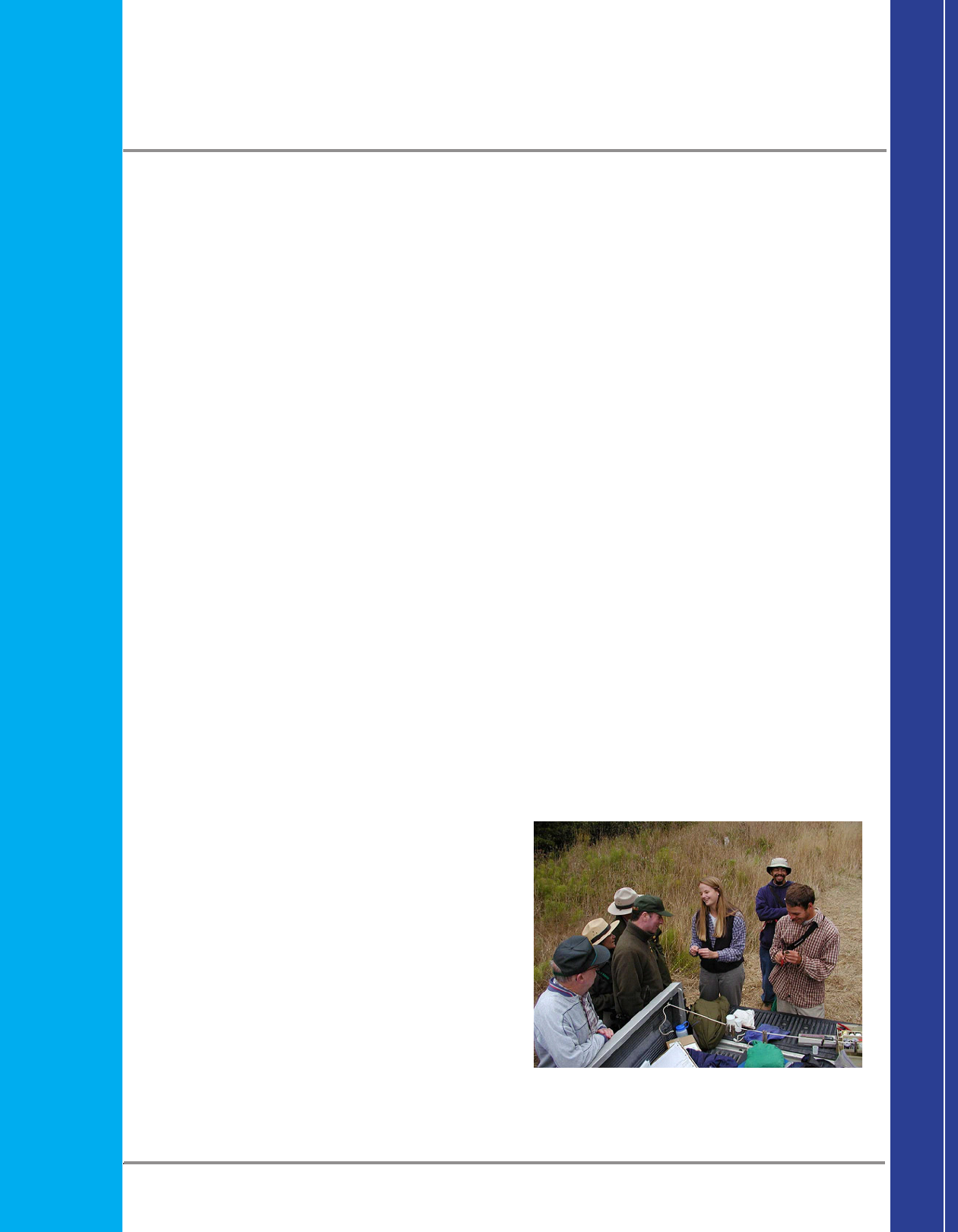

Preserving data quality was listed as another challenge when conducting educational pro-

grams with mist-netting. As with promoting bird safety, preserving data quality starts with making

sure your banding crew members are well trained in the methods of bird banding and data col-

lection. The North American Banding Council (NABC) has produced three publications relevant to

banding passerines (see page 11). Banders can also be certied by NABC, which is a good way to

ensure your banders are highly trained in bird banding techniques.

There are a few other tips for managing groups that

can help maintain data quality. With large groups or

busy capture sites, the extra time it takes to interpret

banding can slow down processing. Having a dedicated

educator trained in bird banding and handling birds

makes a huge difference. The dedicated educator can

take the group aside with one bird, data sheets, and

banding equipment and go through the process slowly

for the group. This enables the banders to continue

processing birds without the extra time and focus

required when interpreting banding. Splitting the group

into two smaller groups also reduces the time it takes to

interpret banding, as smaller groups are easier to man-

age. In addition, banders feel less crowded and pres-

sured with fewer people. If you band at an extremely

busy site, you may need additional staff, volunteers, or

interns on days when groups are visiting. Keep this in

mind and plan accordingly.

Preserving Data Quality

17

Using interpretive tools and materials will enhance your program by enabling you to reach all

types of learners. If you are using a banding laboratory or visitor center, there are more options

for permanent displays and multi-media tools but visual aids can be created and used in a eld

setting as well. The interpretive tools listed in the box below are used at bird observatories in

North America. The most commonly used tools are band recovery statistics, eld guides, and

information on commonly caught species. Having these prepared as posters, handouts, student

worksheets, or displays will enhance your banding demonstration.

Many of these tools can be easily and inexpensively made with a printer and laminating ma-

chine. Some organizations offered their examples for inclusion in this guidebook to be adapted,

duplicated, or purchased as indicated in the Toolbox section, pages 25-37.

Developing Interpretive Tools

Interpretive Tools Used in Mist Netting Demonstrations

Field guides

Student-created eld guide to commonly caught birds (prepared prior to a visit)

One-page laminated eld guide of common species for people to take home

Commonly caught species proles and posters

Banding tools and/or extra banding kit with tools for people to touch

Binoculars

Mounted birds, study skins, and nature center displays

Overheads

Long-term bird monitoring activity (Toolbox page 30)

Skull ossication diagram (Toolbox page 25)

Illustrations of the banding process

Migration maps and band recovery maps (Toolbox page 32)

Video of banding process

Demonstration net or piece of mist net for people to touch

Aerial photos of research site and nets

Bird nests

White board for group data collection

Birds In Hand and Field (Toolbox page 27)

Longevity records (Toolbox page 28)

18

If you are going to spend the time and energy preparing for and offering mist-netting demon-

strations, it is important to advertise it. How you advertise and recruit participants depends upon

your audience. The most common audience type participating in mist-netting demonstrations

is the kindergarten through 12

th

grade category (K-12), followed by community groups, college

groups, and managers. Community groups include members of the public and special interest

groups such as Audubon Societies, Boy and Girl Scouts, naturalists, birders, visiting scientists,

and Elderhostel groups.

K-12 Audience

If you are trying to encourage participation from the K-12 audience, contacting local schools is

the best place to start. Distribute yers to local school districts or schools that include contact

information and critical notes about scheduling. More effective than sending yers is to make

personal contacts with the school principal or teachers. Specically targeting science teachers

in middle and high schools is also effective. Finally, linking this opportunity with school science

standards, both federal and state, will encourage school participation as well (see page 37 for

National Science Education Standards for the U.S.).

Community groups

Distributing yers and making presentations at community meetings is a good way to get the

word out to your local community. Announcements in weekend editions of newspapers, travel

magazines, and newsletters of similar organizations are excellent ways to draw people in. Make

sure you clearly state that group visits must be scheduled in advance, and include appropriate

contact information. If you have a site that is open to drop-in visitors, consider setting a size limit

for what constitutes a group versus a family stopping by. Usually, groups of 5 or less can be eas-

ily handled in a drop-in situation.

Managers and partners

Encouraging managers and partners to visit

mist-netting stations is an excellent way to trans-

late scientic ndings to conservation planners and

partners and secure continued support and fund-

ing. A personal invitation is the best way to involve

managers and partners. When working on publicly

or privately managed land where research on other

taxa may be occurring, consider inviting other biolo-

gists to learn about the bird research and share nd-

ings. This will help avoid conicts in research meth-

ods as well as to encourage collaborative research

programs.

Publicizing Your Opportunity

19

Partnerships

If you do not have education staff available to conduct program promotion, consider partner-

ing with other environmental or conservation education groups. Offer a banding demonstration

as a component of existing programs. For example, local Audubon groups often have dedicated

volunteers or staff members conducting educational programs and could add your mist-netting

demonstration to their programs. This would raise exposure for your organization, educate people

about science and conservation, and increase the diversity of program offerings for the partner

group. The partner could handle publicity and advertising.

Media visits

Inviting the media to observe mist-netting may be a good way to promote your message or to

raise the prole of your organization. However, media representation may be misleading as tech-

nical terms are often not presented accurately. To prevent this, it is critical to have the following

items ready during each visit with a media representative:

• mist-netting fact sheet (Toolbox, page 25-37)

• a handout with the main points you want to emphasize

• commonly caught bird list with bird names spelled accurately to prevent articles about

‘miss nets’ and ‘olive sighted’ ycatchers

• contact sheet with your contact information as well as the names spelled correctly, of all

staff, interns, or volunteers present that day

It is also a good idea to ask to review the nal article, though it is very rare that a writer will

grant you this request. Under-

stand that media representatives

work under tight schedules and

odd hours, often nishing a story

the evening before it goes to print.

Ask about the printing deadlines

and offer to help answer ques-

tions. If a printed article has

mistakes and inaccuracies con-

tact the author and politely point

out the mistakes. Creating a good

relationship with one or two media

contacts will improve the quantity

and quality of your media expo-

sure pieces in the future.

Publicizing Your Opportunity

20

Now that you have prepared your site, hired and trained enough staff and developed a plan for

bird and human safety, you are ready to host a group. Based on my experience conducting mist-

netting demonstrations, I present the following outlines and some specics on terminology and

interpretation.

Conducting a Visit

Visit Outline for groups of 15 or fewer, times are approximations

9:00 Group arrives, greet group at parking area, welcome, introductions,

and program outline—what can the group expect: restrooms, back-

packs, time, terrain.

9:10 Check the nets—go over the rules prior to departing for trail

9:40 Banding site—interpreting banding process and questions

10:10 Other activities: birding, visitor center, nature writing etc. if time

10:30 Both groups together: wrap up, conclusions, review what they learned

and departure

Visit Outline for groups larger than 15, times are approximations

9:00 Group arrives, greet group at parking area, welcome, introductions,

and program outline—what can the group expect: restrooms, back-

packs, time, terrain. Split group.

9:10 Group 1—Check the nets and band birds—go over the rules prior to

departing for trail

Group 2—begin alternative activity: birding, visitor center, nature writ-

ing, bird specimens, etc.

10:00 Switch groups—Group 2—check nets and band birds Group 1—alterna

tive activity

10:50 Both groups together: wrap up, conclusions, review what they learned

and departure

21

Checking the Nets

The following are some tips and suggestions for checking nets with the public. These may

need to be adapted for your site. This section could be copied and given to staff, interns, and

volunteers as a training tool.

Notes for Banders

The following are considerations for taking groups to check mist nets:

Work in pairs: Always have at least two people who can comfortably extract birds from nets when

taking a group on the net trail.

Help each other out: Partners should be aware of how the bird being extracted is caught. If it is

really tangled, one person should take the group to the next net, giving the person extracting the

bird the time and space needed for difcult extractions. This also eliminates fears for bird safety

among the participants.

Know your group: Walk slowly; be aware of the age of your group. Very young and old visitors

may have trouble keeping up with the fast pace of young eld biologists. Stop periodically to let

people catch their breath, and assess the group’s ability. Don’t let the group get spread out.

Enjoy the surroundings: Point out birds ying overhead to the group, take time to talk about the

habitat and listen to bird songs.

Leave extra stuff behind: Have participants leave all backpacks in a safe location at the banding

site. Backpacks and extra stuff may get tangled in mist nets or slow people down along the trail.

Try to make sure everyone sees a caught bird: If you have a split group and you catch a bird

with one group, show the bird to the group engaged in another activity. This can be as brief as

holding the bird for the group engaged in another activity to see. This is particularly important for

sites with low capture rates.

Rules for Visitors

Before you begin the hike to check the nets, it is important, especially with young students, to

go over the rules for your site. How you talk about these rules and what rules you institute will

vary by site. I have summarized some concerns into three rules. The corresponding text is how I

introduce them to children:

1. Stay on the trail

: Who knows what poison oak is? Poison oak is an important part of the

habitat for many bird species. Some birds choose to nest in poison oak and even use the bark

to build their nests. We keep the trails clear of poison oak so if you stay on the trail you won’t

get poison oak. (People often ask if birds get poison oak. No they don’t, but they can spread it to

banders who handle them.)

2. Keep voices down and walk

: Remember, we are about to enter a study area. Who wants

to catch birds today? Great, me too, and we will have a better chance of catching them if we are

walking and talking quietly while we go on the net trail.

3. Keep out of the nets

: The nets are very delicate and can tear easily. If you have any

backpacks you can leave them at the banding area, and as we walk close to the nets, try to keep

Conducting a Visit

22

your arms in (demonstrate how) to make sure your watches or jewelry don’t get caught. (Remem-

ber, some kids and adults will always touch the nets, it’s inevitable. I like to let people touch a

net that does not have birds in it at the beginning of the trail to get it out of their system. Avoid

spending the entire hike telling kids to keep their hands out; there are many more interesting

things to focus on.)

A journey along the trail

Starting at the rst net, have the participants stand a few feet away from the net to view it.

Explain how the net is hard to see by having them look through the net and focus on the vegeta-

tion. When you do this, the net becomes nearly invisible. Using a rolled up bird bag, toss the bag

into the net to show how a bird gets caught. This is a good time to talk about when you open and

close the nets, how often you band birds at this site, and to answer any questions.

Proceed along the trail, again stopping to see how the group is doing. I like to stop at certain

points along the way to point out changes in habitat or interesting notes about the surroundings.

Stop somewhere along the way and have them stand quietly to listen to how many different birds

they can hear.

If you did not get any birds, take the group back to the banding area and show them the

bands and pliers and talk a bit about what you would have done if you had a bird. Some organiza-

tions have a video they play of the mist-netting and banding process. This would be an excellent

tool for sites with a low volume of birds captured.

If you did get birds, take the group to the banding area, and go through the steps of banding

with them.

Interpreting the banding process

Once gathered, wait for the group to quiet down before taking the bird out of the bag. I nd it

works well to have one person band and process the bird while I narrate. It is important to use

basic terms or clearly dene unfamiliar terminology. Terms such as brood patch, ossication, and

even wing chord will need explanation. Here are some ways to talk about the different terminol-

ogy of the banding process.

Brood patch— When birds have eggs in the nest that they need to keep warm or incubate,

they lose the feathers on their belly so that their warm skin comes in contact with the eggs. This

featherless area on a bird’s stomach is called the brood patch. In most cases, only females

develop a brood patch so it is very useful for determining males from females. Show diagrams if

possible.

Conducting a Visit

23

Cloacal Protuberance — This is something that males develop in the breeding season only.

The cloaca is the main organ for fertilization for birds and, when males are ready to breed, it

becomes enlarged. The size of the cloaca can help determine a male from a female. Show dia-

grams if possible.

Molt — We also look at how a bird is molting or changing its feathers. We can sometimes

determine a bird’s age by looking at how it molts its feathers. The specic information we need

to determine a bird’s age from feather molt is outlined in this guide: Guide to Ageing and Sexing

Passerines, Peter Pyle. This is an amazing resource for scientists who mist-net birds, but not

something you would want to take birding with you (let people have a chance to see the guide if

interested).

Skull ossication — When birds rst hatch from an egg they have one thin layer of bone over

their head. You can see right through the rst layer and it looks pink. Then when the second lay-

er grows over the top the bone becomes ossied or fused and it appears white. We look through

the birds’ skin to see if there is a contrast between white bone and pink. If we nd a contrast we

know that the bird is less then one year old. If it is solid white bone then it is at least one year

old. You can use the skull poster as a tool for this (Toolbox, page 25).

Wing Chord — This is a measurement we take on all birds. It is sort of the equivalent of mea-

suring someone’s height. For some bird’s the length of a birds wing can also help us tell males

from females.

Body Weight— We record the weight of each bird, teaching us about the health of a bird and

sometimes to help us tell males from females. (Describe your weighing process — if using a can-

ister, explain that the birds are OK as they go head-rst into the cup. If using a paesola, this may

be a good opportunity for a student to have a hands-on experience. Let them hold the paesola

and read the weight. Make sure you talk about weighing the bag rst.

When nished, let the group watch you release the bird if possible. Please follow the guide-

lines for releasing birds with a group outlined in the Bird and Human Safety section, page 14.

Conducting a Visit

24

As with all educational programs, it is critical to evaluate your ability to successfully conduct and

deliver your message. Program evaluation is important for accountability to a funding agency.

However, program assessment is important for much more (Thomson and Hoffman, 2005).

Assessment is a way to check for understanding and determine if ideas or concepts are being

taught (Colburn, 2003). Assessing your ability to meet the goals of your program enables you to

revise your methods and programs to focus on areas where understanding gaps exist.

Traditional evaluation methods often take the form of written tests, evaluations, and tracking

number of participants. Tracking the number of participants is a good way to determine

participation but may not tell you much about what your audience learned. Written evaluations

are an effective way to capture what people learned, but it can be difcult to encourage

participants to ll out an evaluation on-site after a program. Alternative assessment tools are

more appropriate for informal education programs. Student groups often write thank you letters

or send drawings; these are useful for demonstrating what they learned. Having a post-visit

activity for teachers to conduct in the classroom and asking teachers to share results is another

good idea. Verbally asking students to describe what they learned or enjoyed at the end of a

program is a valid form of evaluation and allows you to immediately address misconceptions,

but this method is difcult to document. Sign-in books can be used to capture comments

from people as they leave your site. Regardless of your specic program goals, some form of

evaluation technique should be used in conjunction with your program.

Toolbox

The following pages contain a set of interpretive materials you may nd useful when conducting

mist-netting demonstrations. You may copy materials right out of this manual for use at your

site, modify them to meet your needs, and in some cases purchase copies from the organization

that created them.

Program Evaluation

25

Skull Ossication Chart (PRBO Conservation Science)-ok to use at your site

Toolbox

Skull Ossification in Young Birds

A tool for ageing birds

First hatched

from egg

Complete

Skull

26

Toolbox

Banding Station Scavenger Hunt, (Klamath Bird Observatory)

Ok to use/modify for your site.

Scavenger Hunt

Welcome to Klamath Bird Observatory! Our scientists use

many tools to help them collect data. They also use many ob-

servation skills to nd birds. Today during your visit at the banding station, see

how many things you can observe on the list. Good luck!

Cloth bags

Mist nets

Clothespins

Bands

Banding pliers

Band removers

Gauge

Calipers

Optivisors

Wing rulers

Data sheets

A hotbox for birds

Flashlight

Radios

Camera

A bird that still has juvenile feathers

A bird caught with a band showing it has been previously caught

Tabular Pyle Guide

27

Birds in Hand and Field, (Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory)

Biologists the world over use banding to study bird migration, populations, and habitat use. This 16-

page booklet is lled with activities for learning about this important research method. Topics include

basic bird identication, migration, data collection, and more. Suitable for grades 1-7, and used in

training adults at bird banding stations. Available in English and Spanish. Cost: $5 plus $2 shipping

and handling. To order, contact Shelly Morrell, Education Division Director, Rocky Mountain Bird

Observatory, 230 Cherry Street, Fort Collins, CO 8052, 970-482-1707 www.rmbo.org

Toolbox

28

Toolbox

Longevity Records Poster, (PRBO Conservation Science)

This is an example of a poster created for the PRBO Bird Banding Lab illustrating longevity records

for commonly caught species. Longevity records for birds can be found at on the BBL website at

www.pwrc.usgs.gov/BBL/homepage/longvrec.htm. OK to modify for your site.

29

Toolbox

Toolbox-Bird Banding Fact Sheet, (Klamath Bird Observatory)

OK to use for your site.

Bird Banding Fact Sheet

What is bird banding?

Bird banding is a method used by scientists to study

birds. Birds are safely caught by scientists and given an

identication band. A band is a small aluminum ring that

ts around the bird’s leg like a bracelet. The band is

engraved with a unique number, allowing scientists to keep

track of each individual bird. No other bird will have the

same number.

Why do scientists band birds?

Putting a band with a unique number on a bird allows scientists to keep track of each individual bird

when it is caught again. This is important for answering questions (testing hypotheses) about birds.

Some of the questions bird banding allows scientists to answer include: How long do birds live?

Where do birds go? What birds are present at this site? How are bird population numbers changing

over time? and How many baby birds were born each year? Answering these questions provides

information useful in protecting birds and their habitats.

How do scientists catch the birds?

The birds are gently caught in soft, ne nets called mist-nets. These nets are stretched between two

poles, usually among trees and bushes. The birds cannot see the nets, so they y into them. Scientists

carefully remove the birds from the nets so they can be banded and released unharmed.

Who bands birds?

Scientists from bird observatories, government agencies, research organizations, and graduate schools

band birds as part of their research programs. In order to band birds you must have a permit and

be trained to safely handle and band birds. All the data collected on birds banded in North America

is kept by the Bird Banding Laboratory of the US Department of the Interior and is available for any

scientist to access.

How many birds are banded each year?

Each year approximately 1.1 million birds are banded. In total, 57 million birds have ever been banded.

What do I do if I nd a banded bird?

If you nd a banded bird report it to 1-800-327-BAND or on the web at

www.pwrc.usgs.gov/BBL/homepage/call800.htm.

30

Toolbox

Warbling Vireo Graphing Activity

(PRBO Conservation Science) - ok to modify for use at your site.

Grades 3 and up (the information and questions can be adapted to the audience)

1. Introduce Banding / Mist-netting

• What is banding and mist-netting?

• Why study birds? (Birds are indicator species, etc.)

• What can we learn from banding birds? (i.e. productivity and survivorship)

2. Introduce Warbling Vireos

• What type of bird is a Warbling Vireo?

• What time of year do we catch them in our nets (get them thinking about Warbling Vireos’ life

cycle, breeding, migration, etc.)?

• Why would we want to study them using mist-nets?

3. Break into groups of 2 students (or keep them together)

• Each group (or individual) will receive a special card containing actual data from PRBO’s Palomarin

Field Station mist-net study, including number of Warbling Vireos captured in the nets during a

specic year.

• Call on students (or groups) to plot each point (you can also choose select points to plot to save

time)

• They must use their card to plot the data point on the white board graph.

• After all points have been plotted, ask a volunteer group to complete the graph by connecting the

data points with a line.

4. Discuss Results

• Ask for volunteers to interpret the graph; What do they think is happening with the Warbling

Vireo population; Do they think having many years of data is important (compare looking at only a

few years versus all years on the graph)?

• What can we do with the data? (i.e. nd out more about the problem by nest searching, use

information for recommendations to land managers, etc.)

• Draw on importance of long-term data by talking about up-down cycles in population numbers.

Suggested Items to Use for Activity:

• Dry erase white board with markers, with a blank graph with grid lines and years on the x-axis

and numbers on the y-axis drawn on in permanent marker, This makes it easier for the students

to nd and plot their data points)

• 28 PRBO Warbling Vireo Data Cards (laminated)

• Yard Stick (to help students with plotting points)

There are a total of 28 laminated cards for students in this activity. Each card represents a data point

and allows students to plot each point on the graph, as explained in the activity outline above.

31

Toolbox

32

Toolbox

Band Recovery Map, (Big Sur Ornithology Lab)

33

Created by PRBO Conservation Science - ok to modify and reproduce.

Commonly asked questions and answers for bird banding demonstrations.

1. Do the bands hurt the birds? No, the band ts around their leg, loose like a bracelet, not

as tight as a watch.

2. Does the band impede their ying? No, studies on captive birds have shown no effect.

The bands for small birds are made of aluminum (the same material soda cans are made from),

and they are very light.

3. Do birds ever die or get hurt in the net? Very rarely. We are very careful to always put

the birds’ safety rst. By watching how the birds are behaving we can tell if the bird is under

stress and we would let a stressed bird go or put it in our hot box to warm up before letting

it go.

4. The birds you are holding seems so calm, why is that? The way I am holding it keeps it

from struggling. Its wings are pressed against the back of my hands and my ngers are actually

on its shoulders.

5. Do you ever catch the same bird twice, or twice in one day? Yes, about 1/3 of

the birds we catch are re-captured. It is really our hope to re-capture birds. That way we

can learn things such as how long birds live (survivorship) and how birds change as they

age. When we re-capture migratory birds from season to season we are able to tell that

that individual survived the winter and migration. We do also catch the same bird in one

day usually this occurs in the breeding season when birds are very distracted and are busy

defending territories and feeding young. Some individuals may learn where the nets are

located, but the fact that we catch them repeatedly even in a day suggests that learning to

avoid the nets is not a major factor in the population declines we notice.

6. If you catch a bird again, do you just let it go or do you still band it? If we catch

a bird with a band already, we still process it, or take all the data, because this can teach us

about how the bird has changed since we last captured it. If we catch the same bird twice in

one day then we weigh it again and release it.

7. Why are you banding birds here? Mist-netting and bird banding allows us to monitor

long-term changes in bird populations and relate them to factors such as weather, restoration,

and habitat change. Banding allows us to determine how long birds live (survivorship) and

how successful the population is at producing young. By understanding these factors we can

better conserve bird populations.

8. Are you part of the National Forest, or Audubon? Fill in answer for your organization/

afliation

9. Do you receive government funding? Fill in answer for your organization/afliation.

10. Where do you get your funding? Fill in answer for your organization/afliation.

11. Can I hold the bird? No, we can’t let you hold the birds, it takes time to learn to safely hold

birds and we need to quickly nish the banding process so we can let the bird go.

Toolbox

Commonly Asked Questions, (PRBO Conservation Science)

34

Bird Banding Brochure, (Rouge River Bird Observatory)

Toolbox

35

Toolbox

Bird Banding Brochure, (Rouge River Bird Observatory)

36

Toolbox

Sample

~ Feedback Form-Teachers~

Your feedback is important to us! We intend to improve the quality of our programs by incorporating

feedback from participants in our mist netting demonstration. We welcome all comments and suggestions

for change.

Do you feel this program contributed something to your science education programs? Please state

why.

____________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________

What did you and your students enjoy most about the mist netting demonstration?

____________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________

What did you and your students enjoy LEAST about the mist netting demonstration?

____________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________

Is there anything you would add or change?

____________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________

Please place any additional comments on a separate page.

Name (optional): ________________________________________________

Afliation: ____________________________________________________

Thank you! Please return this form to us, either via fax or email.

Add your contact information here

37

National Science Standards

The full content standards for life sciences can be found online at the National Science Education

Standards webpage in chapter 6: http://books.nap.edu/html/nses/6a.html.

Peer reviewed literature on effects of bird banding

Ishida, Ken Safety of Ringing Techniques: Load of Ring Weight to Small Birds. Strix, Vol. 11. p. 293-298.

1992. In Japanese with English summ. WR 240 ISSN: 0910-6901

Berggren, Asa; Low, Matthew. Leg problems and banding-associated leg injuries in a closely monitored

population of North Island robin (Petroica longipes) Wildlife Research, 31(5): 535-541; 2004 ISSN:

1035-3712

Haas, William E.; Hargrove, Lori A Solution to Leg Band Injuries in Willow Flycatachers. Studies in

Avian Biology, (26): p. 180; July 2003 ISSN:0197-9922

Other Useful Information

38

Bird Banding Laboratory (BBL). 2005. Memorandum to all banders, MTAB87. USGS Patuxent Wildlife

Research Center, Bird Banding Laboratory, Laurel, MD.

Caduto, Michael J.. (1985). A Guide to Environmental Values Education. Environmental Education Series

#13, UNESCO-UNEP International Environmental Education Programme.

Gardali, T., G. Ballard, N. Nur, and G. R. Geupel. 2000. Demography of a declining population of

Warbling Vireos in coastal California. Condor 102: 601-609 (www.pwrc.usgs.gov/BBL/mtab/mtab87.

htm#permit)

Mead, M., and R. Metraux. 1957. "Image of the Scientist among High School Students: A Pilot Study,"

Science 126: 386-87.

McNamara, C. (1999). Basic Guide to Outcomes-Based Evaluation in Nonprot Organizations with

Very Limited Resources. www.managementhelp.org/evaluatn/outcomes.htm

Nadkarni, N. 2004. Not Preaching to the Choir; Communicating the Importance of Forest

Conservation to Nontraditional Audiences. Conservation Biology 18(3): 602-606/

National Science Board 2002. Science and Engineering Indicators 2002. US Government Printing

Ofce, Washington, D.C.

National Science Foundation (NSF). 2004. Environment, Taking the Long View. Report.

www.nsf.gov/about/history/nsf0050/environment/environment.htm

North American Banding Council (NABC) 2001. The North American Bander’s Study Guide. The

North American Banding Council. Point Reyes Station, CA. (www.nabanding.net/nabanding/pubs.

html).

Pitkin, M. 2005. Useful products for forest bird conservation: A session summary. in California

Partners in Flight, Flight Log Newsletter 15, Summer 2005. 9pp