CROSSING

THE STRAIT

Edited by

Joel Wuthnow, Derek Grossman, Phillip C. Saunders,

Andrew Scobell, Andrew N.D. Yang

China’s Military Prepares for War with Taiwan

CROSSING THE STRAIT

CROSSING THE STRAIT

China’s Military Prepares for

War with Taiwan

Edited by

Joel Wuthnow

Derek Grossman

Phillip C. Saunders

Andrew Scobell

Andrew N.D. Yang

National Defense University

Press

Washington, D.C.

2022

Published in the United States by National Defense University Press. Portions of

this book may be quoted or reprinted without permission, provided that a stan-

dard source credit line is included. NDU Press would appreciate a courtesy copy of

reprints or reviews.

Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely

those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Depart-

ment of Defense or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public

release; distribution unlimited.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022906513

ISBN: 978-0-9968249-8-9 (paperback)

National Defense University Press

300 Fifth Avenue (Building 62), Suite 212

Fort Lesley J. McNair

Washington, DC 20319

NDU Press publications are sold by the U.S. Government Publishing Oce. For

ordering information, call (202) 512-1800 or write to the Superintendent of Docu-

ments, U.S. Government Publishing Oce, Washington, DC 20402. For GPO publica-

tions online, access its Web site at: http://bookstore.gpo.gov.

Book design by John Mitrione, U.S. Government Publishing Oce

Cover image: Amphibious tanks and People’s Liberation Army Navy Marine Corps

forces participate in amphibious landing drill during Sino-Russian Peace Mission

2005 joint military exercise, held in China’s Shandong Peninsula, August 24, 2005

(AP Photo/Xinhua/Li Gang)

is book is dedicated to Rear Admiral Eric McVadon,

U.S. Navy (Ret.), and Alan D. Romberg in appreciation

for decades of friendship and their many contributions

to PLA studies and cross-strait relations.

Foreword

Michael T. Plehn ............................................................................................ ix

Acknowledgments .........................................................................................xi

Introduction

Crossing the Strait: PLA Modernization and Taiwan

Phillip C. Saunders and Joel Wuthnow ........................................................ 1

Part I: China’s Decisionmaking Calculus

1 ree Logics of Chinese Policy Toward Taiwan: An Analytic Framework

Phillip C. Saunders ....................................................................................... 35

2 China’s Calculus on the Use of Force: Futures, Costs, Benets, Risks,

and Goals

Andrew Scobell ............................................................................................65

Part II: PLA Operations and Concepts for Taiwan

3 An Assessment of China’s Options for Military Coercion of Taiwan

Mathieu Duchâtel ........................................................................................87

4 Firepower Strike, Blockade, Landing: PLA Campaigns for a

Cross-Strait Conict

Michael Casey ............................................................................................113

CONTENTSCONTENTS

vii

viii

5 “Killing Rats in a Porcelain Shop”: PLA Urban Warfare in a

Taiwan Campaign

Sale Lilly ......................................................................................................139

Part III: Chinese Forces and the Impact of Reform

6 PLA Army and Marine Corps Amphibious Brigades in a

Post-Reform Military

Joshua Arostegui ........................................................................................161

7 e PLA Airborne Corps in a Taiwan Scenario

Roderick Lee ............................................................................................... 195

8 Getting ere: Chinese Military and Civilian Sealift in a

Cross-Strait Invasion

Conor M. Kennedy .....................................................................................223

9 PLA Logistics and Mobilization Capacity in a Taiwan Invasion

Chieh Chung ...............................................................................................253

10 Who Does What? Chinese Command and Control in a Taiwan Scenario

Joel Wuthnow .............................................................................................277

Part IV: Strengthening Taiwan’s Defenses

11 A Net Assessment of Taiwan’s Overall Defense Concept

Alexander Chieh-cheng Huang ................................................................307

12 Winning the Fight Taiwan Cannot Aord to Lose

Drew ompson ......................................................................................... 321

About the Contributors ............................................................................... 345

Index ................................................................................................................351

E

ven as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has turned attention to Europe,

China is continuing meticulous preparations for a conict with anoth-

er democracy—Taiwan. For more than 30 years, China’s People’s Lib-

eration Army (PLA) has identied Taiwan and the United States as its major

opponents and a conict in the Taiwan Strait as its main contingency. China’s

Communist Party would prefer to win without ghting, but it has tasked the

PLA to develop the military means to coerce Taiwan’s leadership and to be

prepared to seize and occupy the island. Under Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s

tenure, PLA reforms and fast-paced modernization have increased the mili-

tary threat to Taiwan.

e 2022 National Defense Strategy makes clear that the United States will

continue to prioritize peace and stability in the Indo-Pacic region. China is

the pacing challenge for the Department of Defense and Taiwan is the pacing

scenario. Any use of force by the PLA against Taiwan would have serious con-

sequences for U.S. national interests and for the future of Taiwan’s democ-

racy. To meet this challenge, policymakers and strategists need high-quality

insights into Chinese strategic decisionmaking, Chinese military capabilities,

and PLA plans, policies, and systems. We also need to continue rening our

own joint warghting concepts and capabilities.

National Defense University’s Center for the Study of Chinese Military

Aairs is a leading source of high-quality, objective analysis on China and

the Chinese military. For more than 15 years, the center has partnered with

the RAND Corporation and Taiwan’s Council on Advanced Policy Studies to

FOREWORD

ix

organize an annual conference on the Chinese military. is volume is the

fruit of a November 2020 conference focused on providing an up-to-date

public assessment of the Chinese military threat to Taiwan.

e book provides a detailed analysis of the political and military context

of cross-strait relations, with a focus on understanding the Chinese decision

calculus and options for using force, the capabilities the PLA would bring to

the ght, and what Taiwan can do to strengthen its defenses. It concludes that

the PLA has made major advances to prepare itself for a conict across the

Taiwan Strait, but also faces continued challenges and vulnerabilities in some

areas. e book oers suggestions on how Taiwan and the United States can

work together to improve Taiwan’s defenses and increase stability across the

Taiwan Strait. It is highly recommended reading for students and policy prac-

titioners focused on China, Taiwan, and the Indo-Pacic region.

MICHAEL T. PLEHN, Lt Gen, USAF

President, National Defense University

x Foreword

T

his volume is the latest publication from a longstanding series of an-

nual conferences on the People’s Republic of China’s People’s Lib-

eration Army, sponsored by Taiwan’s Council on Advanced Policy

Studies (CAPS), the RAND Corporation, and the U.S. National Defense Univer-

sity (NDU). For their continued support, we are grateful to the leaders of our

respective institutions, including CAPS Secretary-General Andrew N.D. Yang;

RAND’s National Defense Research Institute Director Jack Riley, Arroyo Cen-

ter Director Sally Sleeper, Project Air Force directors Jim Chow and Ted Harsh-

berger, and Acting Director Anthony Rosello; NDU Presidents Vice Admiral

Frederick J. Roegge, USN, and Lieutenant General Michael T. Plehn, USAF; and

Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) Director Laura Junor-Pulzone.

e chapters were originally presented at the 2020 conference, which

was held virtually from November 18 to 20. For keeping things on track,

we thank the moderators: Cortez Cooper, Mark Cozad, T.X. Hammes, An-

drew Scobell, Cynthia Watson, and Andrew N.D. Yang. Also contributing

to a successful conference behind the scenes were RAND colleagues Mark

Cozad and Derek Grossman; RAND IT specialists Sonia Wellington, Da-

vid Cherry, and Carmen Richard; INSS Dean of Administration Catherine

Reese; and INSS colleagues Brett Swaney, Kira McFadden, and Kevin Mc-

Guiness. On the Taiwan side, CAPS thanks Yi-Su Yang and Zivon Wang.

e nal roundtable also enriched the conference by providing wider per-

spectives on Chinese military threats and policy responses. e panelists

included Admiral Richard Chen, Taiwan Navy (Ret.), Michael Coullahan,

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

xi

David Finkelstein, Rear Admiral Michael McDevitt, USN (Ret.), the Honor-

able Randall Schriver, and Andrew N.D. Yang.

e discussants took time out of their busy schedules to oer construc-

tive verbal and written feedback that helped transform conference papers

into book chapters. e discussants included Fiona Cunningham, Bonnie

Glaser, Derek Grossman, Kristen Gunness, Scott Harold, Yuan-Chou Jing, Ma

Chengkun, Che-Chuan Lee, Joanna Yu Taylor, and Kharis Templeman. Sev-

eral chapter authors also received helpful feedback from other colleagues.

We were fortunate to collaborate with the excellent team once again at

NDU Press, which shepherded our earlier volumes e PLA Beyond Bor-

ders: Chinese Military Operations in Regional and Global Context (2021) and

Chairman Xi Remakes the PLA: Assessing Chinese Military Reforms (2019),

and others. e team includes NDU Press Director William T. Eliason, Execu-

tive Editor Jerey D. Smotherman, Senior Editor John J. Church, and Internet

Publications Editor Joanna E. Seich. We also thank many others who helped

turn this into a polished volume, including the editing team at VTR Technical

Resources and Lisa Yambrick and proofreader and indexer Susan Carroll. We

also would like to thank Jill A. Schwartz and Cameron R. Morse at the Defense

Oce of Prepublication and Security Review for their help in stewarding this

publication through the review process.

Finally, the editors would like to acknowledge Tiany Batiste, Margaret

Baughman, CDR Jason Brandt, Maj H.C. Carnice, CAPT Bernard Cole (Ret.),

Jessica Drun, Xiaobing Feng, Sarah Gamberini, LTC Joshua Goodrich, Chris-

tine Gramlich, MAJ Michelle Haines, Kyle Harness, Danielle Homestead, Col

Kyle Marcrum, Capt Joshua L. Nicholson, Corrie Robb, MSgt Daniel Salis-

bury, Meghan Shoop, CPT Dereck Wisniewski, LtCol John Kintz, Lt Col Jerey

Wright, MAJ Justin Woodward, Beth Wootten, and CPT Xiaotao Xu for their

help in proofreading the manuscript.

xii Acknowledgments

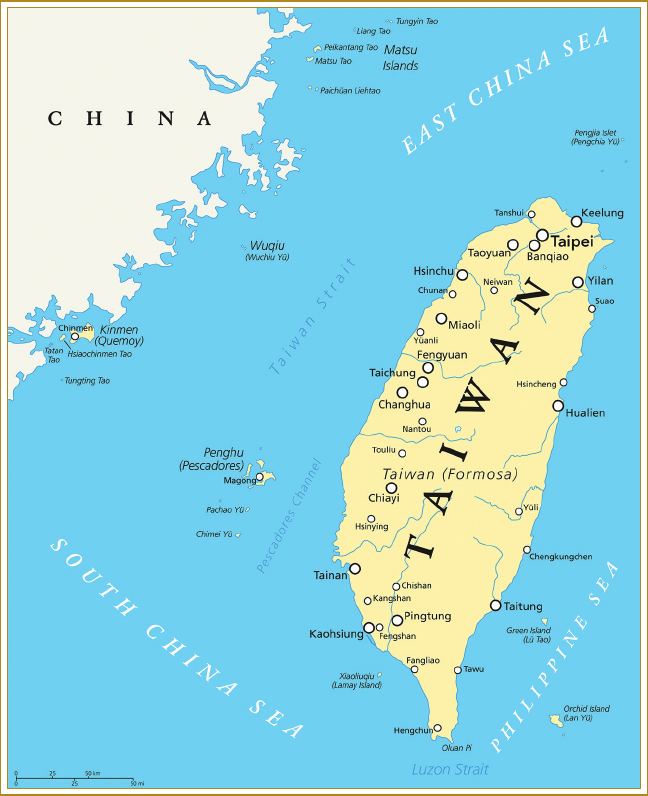

Map 1. Taiwan

I

n an atmosphere of increasing U.S.-China strategic competition, Taiwan

stands out as the issue with the greatest potential to trigger a major war

between the United States and the People’s Republic of China (PRC), two

nuclear-armed powers. e stakes are high for both countries and for the

23 million people of Taiwan. Moreover, the issue is becoming increasingly

militarized as China’s military, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), seeks to

develop the capabilities needed to achieve unication through coercion, in-

cluding in the face of potential U.S. military intervention on Taiwan’s behalf.

is introductory chapter begins with a concise review of how the cur-

rent situation developed, including a review of the policy positions and the

stakes for China, Taiwan, and the United States. It then reviews the impact

of PLA modernization on the cross-strait military balance and on the PLA’s

ability to execute the major military options available to Chinese leaders. e

third section reviews the current debate on when the PLA might be able to

conduct the most demanding option—an amphibious invasion of Taiwan—

and what factors might inuence the Chinese calculus about whether to pur-

sue forced unication. e fourth section presents ve key ndings from the

book, followed by brief summaries of the individual chapters. e conclusion

INTRODUCTION

Crossing the Strait:

PLA Modernization and Taiwan

Phillip C. Saunders and Joel Wuthnow

1

2 Saunders and Wuthnow

considers the relative role of military and political factors in determining de-

terrence and stability in the Taiwan Strait.

Background and Stakes of the Taiwan Issue

For Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders, Taiwan is an integral part of Chi-

na that was forcibly seized by Japan in 1895 following the Sino-Japanese War

and which became a haven for the Republic of China (ROC) government and

military after their 1949 defeat in the Chinese Civil War. Taiwan is thus con-

nected both to the Chinese nationalist goal of restoring China’s sovereignty

and territorial integrity after the so-called century of humiliation and to the

CCP’s nal political victory over the Chinese Nationalist Party (the Kuomint-

ang, or KMT). CCP leaders have pledged their commitment to the goal of uni-

cation and have repeatedly expressed willingness to ght to prevent Taiwan

independence, including in the 2005 Anti-Secession Law that authorizes the

use of “non-peaceful means” if necessary. Taiwan’s status is a sensitive do-

mestic political issue, with CCP leaders vulnerable to criticism by national-

ists inside and outside the party if they are viewed as too weak in defending

China’s “core interest” in sovereignty and territorial integrity. Since 2017, CCP

leaders have linked Taiwan unication to “the great rejuvenation of the Chi-

nese people,” which is to be achieved by 2049, creating an implicit deadline.

1

For the United States, support for Taiwan coalesced in the context of ear-

ly Cold War anti-Communist sentiment: Washington supported the ROC as

the sole legitimate government of all China for more than two decades. Tai-

wan’s status was a major issue in the U.S. opening to China in the 1970s, with

U.S. political leaders seeking to avoid the domestic and international costs of

abandoning Taiwan to the Communist regime in China. e eventual solu-

tion, worked out in three U.S.-China joint communiques, was for the United

States to terminate its defense treaty with the ROC and withdraw U.S. military

forces from Taiwan, shift diplomatic recognition to the PRC, and maintain

only unocial relations with the people on Taiwan. Beijing asserted that Tai-

wan was an integral part of China, while the United States acknowledged this

position without formally accepting it.

2

e United States enacted the 1979

Taiwan Relations Act (TRA) to provide the legal basis for its unocial rela-

tions with Taiwan. Among other things, the TRA requires the United States

to make defensive arms available to Taiwan and states that it will “consider

Introduction 3

any eort to determine the future of Taiwan by other than peaceful means,

including by boycotts or embargoes, a threat to the peace and security of the

Western Pacic area and of grave concern to the United States.” e TRA also

states that U.S. policy is to retain the capability to resist the use of force or

coercion to undermine Taiwan’s security.

3

Although the United States does not have a formal commitment to defend

Taiwan, the TRA’s language and decades of policy have linked the credibility

Map 2. Pratas and Taiping islands, marked in black

4 Saunders and Wuthnow

of U.S. regional alliance commitments to its actions regarding Taiwan. U.S.

stakes deepened further with Taiwan’s democratization in the late 1980s and

early 1990s, which increased Taiwan’s appeal relative to the authoritarian

PRC regime and strengthened U.S. political sympathy and support for Tai-

wan, especially in Congress.

4

Moreover, some U.S. strategists have come to

view a Taiwan not under PRC control as having signicant geopolitical value

in limiting PLA power projection capability.

5

Recent testimony by a Biden ad-

ministration ocial implied that U.S. policy might accept this view and seek

to prevent unication rather than simply shape the procedural conditions

under which negotiations between China and Taiwan take place.

6

us, the

stakes are high for Washington in terms of domestic politics, the credibility of

U.S. alliance commitments, and the regional balance of power.

For more than two decades after its 1949 defeat in the Chinese Civil War,

the authoritarian KMT government ruling Taiwan beneted from a formal

security alliance with the United States and U.S. diplomatic support for its po-

sition that the ROC was the sole legitimate government of all China, and thus

entitled to membership in the United Nations (UN) and control of China’s

permanent seat in the UN Security Council.

7

e KMT government main-

tained the goal of overthrowing the CCP and regaining control of Mainland

China, agreeing that the mainland and Taiwan were both part of a larger Chi-

na. Like the PRC, the ROC government rejected the notion of dual represen-

tation and insisted that countries choose between diplomatic relations with

the PRC or the ROC. is position eventually became untenable as the ROC

was expelled from the United Nations in 1971 and more and more countries

switched diplomatic relations to the PRC, including the United States in 1979.

is left Taiwan internationally isolated, with few formal diplomatic allies

and only unocial relations with most major countries.

Taiwan’s attitude toward China changed with democratization in the

late 1980s and early 1990s, which ended KMT authoritarian rule and allowed

other political parties to compete for power, including the pro-independence

Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Taiwan’s government (and its policy

toward China) became more responsive to the concerns of the native Tai-

wanese who constitute the majority of the population.

8

e traditional ROC

position is that the ROC government has sovereignty over both Taiwan and

Mainland China, but in practice only exercises jurisdiction over the main

Introduction 5

island of Taiwan; various oshore islands such as the Penghus, Pratas/Dong-

sha, Matsu, Jinmen, and Wuchiu; and Taiping/Itu Aba Island in the South

China Sea.

9

(See map 2 showing Pratas/Dongsha Island and Taiping/Itu Aba

Island, respectively.)

e issue of Taiwan’s relationship with China is highly contested, but

public opinion on Taiwan strongly supports the continuation of the current

status quo and the population increasingly identies as Taiwanese rather

than Chinese.

10

Credible PRC threats to use force deter a declaration or refer-

endum that would formally assert Taiwan’s independence. At the same time,

the current DPP government has refused to acknowledge that Taiwan is part

of China, arguing that Taiwan is already an independent sovereign state and

that a formal declaration of independence is unnecessary. is position is

in great tension with the PRC’s “one China principle” and ultimate goal of

unication as well as the KMT’s acceptance of the 1992 Consensus, which

involved a vague commitment to one China.

11

is disagreement about Tai-

wan’s exact status relative to China is the fundamental basis of the political

dispute between Beijing and Taipei.

Despite these diering interpretations, this ambiguous “one China”

framework has served the minimal needs of political leaders and people in

China, Taiwan, and the United States for more than 40 years, supporting eco-

nomic growth, development of robust cross-strait economic and cultural ties,

and political development of Taiwan’s democracy. Although political ten-

sions have waxed and waned over time, the CCP’s “reform and opening up”

policy and the interest of the Taiwan government and business community in

exploiting economic opportunities in China have allowed cross-strait trade

and investment to grow to the point where China is Taiwan’s largest market,

and the two economies are deeply intertwined despite Taiwan government

eorts to reduce economic dependence on the mainland.

Nevertheless, long-term political, military, and economic trends are

eroding the stability of the status quo and increasing the potential for military

conict.

12

China’s policy toward Taiwan shifted from its initial emphasis on

“liberating Taiwan” by force to a focus on achieving “peaceful unication,”

but CCP leaders have refused to rule out the use of force, either to prevent

Taiwan independence or to compel unication under certain conditions.

13

Taiwan’s status is fundamentally a political question, but the military balance

6 Saunders and Wuthnow

between China and Taiwan and between China and the United States is an

increasingly important factor shaping cross-strait relations.

e importance and sensitivity of these issues is illustrated by China’s

response to Taiwan President Lee Teng-hui’s June 1995 unocial visit to the

United States. Lee’s visit triggered a military crisis that included the PLA r-

ing ballistic missiles near Taiwan’s two main harbors prior to the March 1996

presidential election and President Bill Clinton ordering the deployment of

two U.S. aircraft carriers to waters near Taiwan as a military show of force.

14

Since then, a Taiwan contingency has become the principal focus of Chi-

nese military modernization, and the PLA has assumed that the U.S. military

would intervene on Taiwan’s behalf in a conict. is has fueled PLA eorts

to develop the capabilities necessary to invade Taiwan, including advanced

antiaccess/area-denial (A2/AD) systems to counter a potential U.S. military

intervention. e PLA’s successes in military modernization and reform in-

creasingly challenge Taiwan’s ability to defend itself in the face of numerically

and qualitatively superior Chinese forces and raise the costs and risks of U.S.

intervention on Taiwan’s behalf.

A Changing Military Balance

e military balance between Taiwan and China has shifted decisively in

Beijing’s favor over the last three decades. Taiwan has historically benet-

ed from the inherent defensive advantages provided by its island geogra-

phy and a technological edge based on access to advanced U.S. weapons

and training. PLA modernization has eroded Taiwan’s technological ad-

vantage, and the PLA now maintains qualitative advantages across the

spectrum of conict. Taiwan’s conventional force capabilities are out-

matched by the PLA’s size and advantages in personnel, weapon systems,

and defense budgets. e table compares Taiwan military forces with the

PLA’s Eastern and Southern theater commands (TCs) that would be most

involved in a Taiwan scenario to establish a baseline of the conventional

military challenge Taiwan faces.

15

In addition to the forces depicted in the table, the PLA Rocket Force oper-

ates 100 ground-launched cruise missile launchers, 250 short-range ballistic

missile launchers, and 250 medium-range ballistic missile launchers with the

collective capability of ring at least 1,900 missiles.

16

Introduction 7

e PLA has several options to apply its military capabilities against

Taiwan, including low-level military coercion, coordinated missile and air-

strikes, a blockade, and a full-edged invasion of the island. (ese options

are detailed and assessed more fully in the chapters by Mathieu Duchâtel and

Michael Casey in this volume.) However, even with China’s considerable mil-

itary advantages, there would still be signicant costs and risks in trying to

resolve Taiwan’s status by force.

e PLA has periodically employed military coercion against Taiwan in the

form of targeted military exercises, demonstrations of force, and deployments.

ese actions have sought to signal China’s capability and resolve while stay-

ing in the gray zonethat is, below the level of lethal force. However, low-level

coercion could potentially grow to include limited use of lethal force, such as

seizing oshore islands controlled by Taiwan or kinetic attacks against Taiwan’s

Table. Comparison of PLA and Taiwan Military Forces

Capability PLA Eastern and Southern

TCs

Taiwan

Ground Force Personnel 416,000 88,000 (active duty)

Tanks 6,300 across PLAA 800

Artillery Pieces 7,000 across PLAA 1,100

Aircraft Carriers 1 (2 total) 0

Major Surface Combatants 96 (132 total) 26

Landing Ships 49 (57 total) 14

Attack Submarines 35 (65 total) 2 (diesel attack)

Coastal Patrol Boats

(Missile)

68 (86 total) 44

Fighter Aircraft 700 (1,600 total) 400

Bomber Aircraft 250 (450 total) 0

Transport Aircraft 20 (400 total) 30

Special Mission Aircraft 100 (150 total) 30

Source: Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s

Republic of China 2021 (Washington, DC: Office of the Secretary of Defense, 2021), 161–162.

8 Saunders and Wuthnow

infrastructure. Some actions have come in response to specic Chinese con-

cerns about possible movement toward Taiwan independence, such as the

1995–1996 Taiwan Strait Crisis and PLA deployments in 2008 during the nal

months of Chen Shui-bian’s presidency. Although China used only limited mil-

itary coercion for most of Ma Ying-jeou’s presidency (2009–2016), it has ramped

up military pressure against Taiwan since then, citing Tsai Ing-wen’s refusal to

accept the 1992 Consensus as justication. ese actions have included island

landing exercises, circumnavigation of Taiwan by PLA Navy aircraft carriers

and aircraft, and repeated intrusions into Taiwan’s Air Defense Identication

Zone.

17

e PLA appears to have escalated the number and intensity of these

actions in 2020 and 2021 to increase military pressure on Taiwan.

A joint repower strike campaign would employ PLA missile and air strikes

to inict sucient damage to compel Taiwan to accept Chinese terms. e rst

phase would employ precision strikes to degrade Taiwan’s air and missile de-

fenses and achieve air superiority. A second phase of attacks would strike mil-

itary and infrastructure targets to inict punishment on Taiwan’s leaders and

population. China has the military capabilities to inict heavy punishment on

Taiwan, but these attacks would generate signicant international reaction and

provide time for the United States to mobilize and deploy forces. Moreover, the

historical record indicates that strategic bombing campaigns tend to produce

rallying eects rather than cause leaders and the public to surrender.

18

Taiwan

also has its own oensive missile capabilities that it could use to mount limited

strikes against the mainland in response. Taiwan’s 2021 Quadrennial Defense

Review and 2019 National Defense Report address these realities in depth and

highlight the training, defense spending increases, and foreign military sales

acquisitions to signicantly add risk and cost to this option for the PLA.

19

A joint blockade campaign would employ kinetic blockades of maritime

and air trac to Taiwan to cut o vital imports. e blockade would likely

include mines, missile strikes, and possible seizures of Taiwan’s oshore is-

lands and could be tailored in scope and intensity.

20

A full blockade could

employ the entire suite of PLA capabilities, including electronic warfare, cy-

ber warfare, and information operations. Chinese submarine warfare capa-

bilities and the PLA’s ability to launch antiship cruise missiles and ballistic

missiles from a variety of platforms would greatly complicate Taiwan’s de-

fenses. A blockade would disrupt commercial shipping in the region and

Introduction 9

generate signicant international reactions. e extended duration of the

blockade necessary to compel Taiwan into accepting Chinese terms would

have substantive military, economic, and political costs and provide time for

the international community to impose sanctions and for the U.S. military to

deploy forces to intervene militarily. is option carries substantial costs and

risks with uncertain prospects of compelling Taiwan to capitulate.

A joint island landing campaign would involve a full amphibious invasion

that might build on prior blockade and strike campaigns. is option has the

highest military costs and risks but oers the prospect of a decisive military vic-

tory. e PLA routinely exercises the military skills that would be employed in

an amphibious invasion.

21

An invasion would require a massive mobilization of

PLA forces, equipment, and logistics capabilities. e rst phase would involve

eorts to degrade Taiwan’s air and naval defenses in preparation for an am-

phibious assault. e PLA would utilize precision ballistic and cruise missile

strikes against Taiwan’s air and missile defenses, precision long-range artillery,

airstrikes with medium-range bombers and ghters, and antiship cruise mis-

sile and submarine attacks against Taiwan’s naval assets. Taiwan would employ

its air and missile defense and air force and naval assets to defend targets and

contest PLA eorts to gain maritime and air superiority.

22

e PLA would then

need to execute an amphibious assault to establish a beachhead on Taiwan

and an airborne/air assault attack to try to seize an aireld and a port facility

that could allow the PLA to use civilian transportation assets to provide air and

sea lift. e PLA would then have to land sucient ground combat forces to de-

feat Taiwan’s ground forces and provide sucient ammunition, fuel, and other

supplies to support these forces during combat operations.

Since the 1995–1996 Taiwan Strait Crisis, the PLA has assumed that the

United States would intervene in a Taiwan conict and has sought to deter or

delay U.S. intervention via an array of A2/AD capabilities that would raise the

costs and risks for U.S. forces operating near China.

23

ese include advanced

diesel submarines, which could attack U.S. naval forces deploying into the

Western Pacic; surface-to-air missiles such as the Russian S-300, which could

target U.S. ghters and bombers; and antiship cruise and ballistic missiles op-

timized to attack U.S. aircraft carrier battle groups.

24

China has invested in a

range of accurate conventional missiles that could target the bases and ports

the U.S. military would use in a conict, including most recently the DF-17

10 Saunders and Wuthnow

intermediate-range ballistic missile with a hypersonic glide vehicle. China has

also sought to exploit U.S. military dependence on space systems by develop-

ing a range of antisatellite capabilities that could degrade, interfere with, or di-

rectly attack U.S. satellites and their associated ground stations. It has invested

in cyber capabilities to collect intelligence and to degrade the U.S. military’s

ability to employ computer networks in a crisis or conict. In a conict, the

PLA would attempt to use multidomain attacks to paralyze U.S. intelligence,

communications, and command and control systems and force individual

units to ght in isolation, at a huge disadvantage.

25

China is also likely to deal

with the risks of U.S. intervention by seeking to win a quick victory before the

United States could fully deploy its forces to the theater, thereby presenting the

United States with a hard-to-reverse fait accompli.

e implications for the U.S. ability to defend Taiwan are signicant.

While the PLA has not caught up to the U.S. military in aggregate military ca-

pabilities, it does not need parity to frustrate U.S. intervention in a short con-

ict on its immediate periphery.

26

e RAND Corporation’s 2015 evaluation

of U.S.-China military force capability trends found that the United States had

“major advantages” in 7 of 10 critical capability areas in a Taiwan scenario

in 1996 but that by 2017 the United States would have clear “advantages” in

only three categories, and the PLA would enjoy advantages in two: its ability

to attack U.S. airbases and carriers.

27

China’s advances in ballistic missiles,

cruise missiles, and modern diesel attack submarines now give it capabilities

it did not have during the 1995–1996 stando, which might aect how the U.S.

military chooses to forward deploy forces.

28

Of course, Taiwan and the United States are not standing still. Taiwan’s

Overall Defense Concept, described in the chapters by Alexander Chieh-

cheng Huang and Drew ompson, seeks to use asymmetric capabilities to

increase the challenges for invading PLA forces. ese include investments

in rapid mine deployments and mobile missile platforms that would target

invading forces and complement Taiwan’s geographic advantages. e con-

cept also includes investments to make Taiwan’s forces more survivable and

eective in preventing a post-landing breakout. Taiwan’s 2021 Quadrennial

Defense Review and 2019 National Defense Report spend considerable time

highlighting the training, defense spending increases, and foreign military

sales acquisitions to add risk and cost to PLA military options.

29

Introduction 11

e Department of Defense (DOD) is working to adapt U.S. weapons and

operational concepts to ght the PLA in an A2/AD environment, including

increased forward deployment of forces and supplies to overcome the “tyr-

anny of distance.” is thinking is evident in the 2018 National Defense Strat-

egy and in the joint concept of “globally integrated operations” that seeks to

leverage information and U.S. global capabilities to achieve decisive strate-

gic eects in regional contingencies. At the request of Congress, then U.S.

Indo-Pacic Command commander Admiral Philip Davidson developed

a 6-year, $20 billion investment program for the U.S. military to “regain the

advantage” over China in the Indo-Pacic region. Congress appears likely to

continue to fund this request.

30

e U.S. Services all have active eorts under way to adapt systems and

doctrine to meet A2/AD threats, with a clear focus on China. For the Navy, this

involves eorts to disrupt the “kill chain” necessary for Chinese missiles to lo-

cate and target U.S. carriers and to develop the ability to operate and reload ship

armaments from a diverse set of nontraditional port facilities. For the Air Force,

this involves eorts to develop both stando and penetrating platforms

31

and

improve the Service’s ability to conduct expeditionary, distributed operations

from austere airelds with reduced logistics and maintenance requirements,

which the Air Force calls Agile Combat Employment.

32

e Army has created

new “multidomain task forces” that combine artillery and precision strike ca-

pabilities with a range of cyber, electronic warfare, space, and intelligence ca-

pabilities to operate within and degrade an adversary’s A2/AD capabilities. e

initial pilot program was conducted under U.S. Army Pacic, and the rst oper-

ational task force has been established at Joint Base Lewis-McChord, which is

aligned to the Indo-Pacic theater.

33

e Marine Corps has made a major shift

in its force modernization over the next decade to improve its ability to conduct

expeditionary advanced base operations in contested environments.

34

Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin III has repeatedly described China as

the “pacing challenge” for DOD. In a December 2021 speech, he highlighted

how DOD has been stepping up its eorts on China:

Our China Task Force sharpened the Department’s priorities and charted a

path to greater focus and coordination. We made the Department’s larg-

est-ever budget request for research, development, testing, and evaluation.

And we’re investing in new capabilities that will make us more lethal from

12 Saunders and Wuthnow

greater distances, and more capable of operating stealthy and unmanned

platforms, and more resilient under the seas and in space and in cyberspace.

We’re also pursuing a more distributed force posture in the Indo-Pacic—

one that will help us bolster deterrence, and counter coercion, and operate

forward with our trusted allies and partners.

And we’re developing new concepts of operations that will bring the Amer-

ican way of war into the 21

st

century, working closely with our unparal-

leled global network of partners and allies.

Austin highlighted “integrated deterrence” as the cornerstone concept of a

new National Defense Strategy that was released in early 2022. He described

it as “integrating our eorts across domains and across the spectrum of con-

ict to ensure that the U.S. military—in close cooperation with the rest of the

U.S. Government and our allies and partners—makes the folly and costs of

aggression very clear.”

35

Assessing the Risks

Most military analysts would agree that the PLA has made considerable mili-

tary advances. Secretary Austin stated in December 2021 that “two decades of

breakneck modernization” have put the PLA on pace “to become a peer com-

petitor to the United States in Asia—and eventually around the world.”

36

In its

2021 annual report, the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commis-

sion found that “improvements in China’s military capabilities have funda-

mentally transformed the strategic environment and weakened the military

dimension of cross-strait deterrence.”

37

e PLA clearly has the capability to apply low-level coercive pressure

and to conduct air and missile strikes against Taiwan and probably has the

capability to execute a blockade absent U.S. intervention. Disagreements

come in assessing the PLA’s capability to execute the most demanding mil-

itary option—an amphibious invasion of Taiwan—especially in the face of

U.S. intervention. e Oce of the Secretary of Defense 2021 report on the

PLA highlights the challenges and risks:

Large-scale amphibious invasion is one of the most complicated and di-

cult military operations, requiring air and maritime superiority, the rapid

Introduction 13

buildup and sustainment of supplies onshore, and uninterrupted support.

An attempt to invade Taiwan would likely strain PRC’s armed forces and

invite international intervention. ese stresses, combined with the PRC’s

combat force attrition and the complexity of urban warfare and counter-

insurgency, even assuming a successful landing and breakout, make an

amphibious invasion of Taiwan a signicant political and military risk for

Xi Jinping and the Chinese Communist Party.

38

Some have expressed concern that the PLA might acquire the ability to

mount an invasion soon. In March 2021, Admiral Philip Davidson, then com-

mander of U.S. Indo-Pacic Command, told Congress that China’s threat to

Taiwan could manifest “in the next six years.”

39

Davidson’s judgment was not

a coordinated U.S. Government position, and other DOD ocials have not

repeated this assessment.

40

Davidson’s successor, Admiral John Aquilino, de-

clined to oer a specic time estimate but testied that China considers es-

tablishing control over Taiwan to be its “number one priority” and that “this

problem is much closer to us than most think.”

41

e U.S.-China Economic

and Security Review Commission judged in its 2021 report that “PLA leaders

now likely assess they have, or will soon have, the initial capability to conduct

a high-risk invasion of Taiwan if ordered to do so.”

42

Similarly, Taiwan Min-

ister of Defense Chiu Kuo-cheng told the Taiwan legislature that Mainland

China will have the ability to mount a full-scale invasion of Taiwan by 2025,

though he also noted that Chinese leaders would still “need to think about

the cost and consequence of starting a war.”

43

Oriana Skylar Mastro argued in Foreign Aairs in July 2021 that advances

in military modernization mean that Chinese leaders now consider a military

campaign to take back Taiwan “a real possibility” and that “once China has

the military capabilities to nally solve the Taiwan problem, Xi could nd it

politically untenable not to do so” due to strong nationalist pressures.

44

She

sketches PLA military options and argues that the PLA could already execute

the less demanding scenarios, while noting that an amphibious assault on the

island “is far from guaranteed to succeed.” Nevertheless, Mastro argues that

“Chinese leaders’ perceptions of their chances of victory will matter more

than their actual chances of victory.” She argues that China would hope for a

short, decisive campaign that would limit costs, but might believe that it has

social and economic advantages that would help it prevail over the United

14 Saunders and Wuthnow

States in a protracted war. She acknowledges that economic and diplomat-

ic costs of war would be part of Beijing’s decision calculus but argues that

Chinese leaders may believe that these costs are signicantly less than U.S.

decisionmakers and analysts assume. Mastro concludes that Xi “may believe

he can regain control of Taiwan without jeopardizing his Chinese dream.”

Other scholars question various aspects of this assessment. In a rejoin-

der published in the next issue of Foreign Aairs, Rachel Esplin Odell and Eric

Heginbotham argue that the PLA’s chances of succeeding in a cross-strait inva-

sion are poor today and will remain so for at least a decade.

45

ey cite limita-

tions in PLA lift and logistics capability and argue that “the PLA still lacks the

naval and air assets necessary to pull o a successful cross-strait attack. Just as

important, it suers from weaknesses in training, in the willingness or ability

of junior ocers to take initiative, and in the ability to coordinate ground, sea,

and air forces in large, complex operations.” Odell and Heginbotham also ques-

tion whether CCP leaders are eager to resolve the situation with force, noting

that “although some of these options are more realistic than others, all would

carry immense risk. . . . Beijing is unlikely to attempt any of them unless it feels

backed into a corner.” Similarly, Bonny Lin and David Sacks agree that “it is

far from clear that China could defeat Taiwan’s military, subdue its population,

and occupy and control its territory. Nor is it clear that the PLA could hold o

any U.S. forces that came to Taiwan’s aid or that Beijing would be willing to un-

dertake a campaign that could spark a larger and far more costly war with the

United States.”

46

ey cite the likely costs of using force, arguing that “a Chinese

invasion would invite signicant international political, economic, and diplo-

matic backlash that could undermine China’s political, social, and economic

development goals. It would also spur the formation of powerful anti-China

coalitions, bringing to fruition Beijing’s long-standing fear of “strategic encir-

clement” by powers aligned against it.” us, despite the PLA’s considerable

modernization gains over the last 20 years, experts continue to debate whether

and when it will be able to invade at a cost and risk acceptable to CCP leaders.

Key Conclusions

is edited volume contributes to the debate by addressing the problem at

three levels: China’s decisionmaking calculus, its military capabilities and

operations, and potential policy responses by Taiwan and the United States.

Introduction 15

It contains up-to-date analysis from multiple perspectives, including schol-

ars from the United States, Taiwan, and France and analysis by academics,

think-tank experts, and government analysts. e analysis draws on a wide

range of sources, including PLA internal writings about military campaigns

and the logistics and transportation requirements for an invasion of Taiwan.

e analysis also looks beyond hardware to consider how recent orga-

nizational reforms and revised command and control arrangements would

aect the PLA’s ability to conduct complicated, high-risk integrated joint op-

erations in the face of opposition by Taiwan and U.S. military forces. It builds

on previous books produced from the Taiwan’s Council of Advanced Policy

Studies–RAND Corporation–National Defense University conference series.

47

e analysis also digs deeper into some underappreciated areas, such as PLA

urban warfare, logistics, and airborne capabilities.

While looking at China’s military threat to Taiwan through dierent lens-

es, the contributors to this volume reached several common conclusions.

First, any Chinese decision to use force is much more likely to result from

a deliberate cost-benet calculus incorporating both domestic and external

considerations than from unintended escalation. Andrew Scobell emphasiz-

es domestic economic and political resilience as keys to the use of force—a

Chinese Communist Party that sees itself as “ascendant” and buered from

sanctions and other predictable consequences might accept the risks of a

war to resolve a remaining obstacle to “national rejuvenation,” while a par-

ty struggling to govern a “stagnant” mainland might conclude that the risks

outweigh the benets. Other authors assess that upgraded hardware and a

more cohesive command structure following the reforms could increase the

leadership’s condence in the PLA’s ability to act decisively while keeping es-

calation at an acceptable level.

Political trends in Taiwan are also likely to inform China’s calculus. Phillip

Saunders argues that low support for unication in Taiwan, which has dimin-

ished further with China’s dismantling of individual freedoms in Hong Kong

and repression against ethnic Uighurs in Xinjiang, has reduced China’s con-

dence in the prospects for a settlement based on a “one country, two systems”

model. For Beijing, the closing of other options increases the relative attrac-

tiveness of military intimidation (and the potential use of force should coer-

cion fail) to prevent a slide toward Taiwan independence in the near term and

16 Saunders and Wuthnow

to convince Taiwan’s leadership to accept reconciliation on China’s terms in

the future. Nevertheless, as Mathieu Duchâtel notes, Beijing might be cautious

about more provocative tactics short of war, such as the seizure of one of Tai-

wan’s outlying islands, that leave Taiwan’s leadership intact and might galva-

nize greater support for independence, rather than cowing Taiwan’s public.

For some authors, the U.S. factor is also prominent in Chinese decision-

making. Drew ompson and Alexander Chieh-cheng Huang both argue

that increasing military coordination between the two sides and continued

U.S. arms sales are essential for improving Taiwan’s defenses, thus enhancing

deterrence by denial and raising the stakes for Beijing, which would prefer

not to have to ght a war with the United States. From a military perspective,

however, Michael Casey emphasizes that Chinese anticipation of U.S. inter-

vention—which is already assumed in PLA doctrinal writings—encourages

Beijing to prefer an invasion over less extreme options, such as a blockade,

that would give the United States time to mobilize forces across the Western

Pacic and assemble a broader coalition.

Second, while the prospects for peaceful unication are narrowing, Chi-

na’s menu of military intimidation and warghting options is expanding.

Peacetime saber-rattling, which is most useful in dissuading Taiwan’s pur-

suit of de jure independence, has become more routine and varied. Joshua

Arostegui assesses that Beijing has used amphibious exercises to intimidate

Taiwan’s public: while part of the annual training cycle, the PLA has publi-

cized some exercises to underscore China’s resolve and capabilities to Taiwan

and the United States. Mathieu Duchâtel tracks the dramatic expansion of

Chinese ghter incursions across the midline of the Taiwan Strait and the in-

creasing tempo and complexity of PLA Air Force (PLAAF) and naval aviation

ights within Taiwan’s southwestern Air Defense Identication Zone. Such

operations serve multiple goals, such as normalizing more intense military

activities, testing U.S. resolve, deterring Taiwan independence, and catering

to a nationalistic domestic audience.

Authors also discuss a variety of military measures that Beijing has not

yet employed. Duchâtel assesses that the PLA could seize an outlying island

such as Dongsha/Pratas to gradually extend its control over territory cur-

rently held by Taiwan—a higher risk version of the “salami-slicing” tactics

that China has used in the South China Sea. He also describes an escalating

Introduction 17

series of cyber attacks against Taiwan, including targeting civilian infra-

structure, as a possible next step in China’s pressure campaign.

48

Higher

forms of coercion discussed in Chinese writings, and likely within current

PLA capabilities, include missile bombardments or a maritime, air, and in-

formation blockade. As Michael Casey discusses, these campaigns could be

used in isolation to attempt to force Taiwan’s leaders to the negotiating ta-

ble or to set conditions for an invasion. Joshua Arostegui notes that China’s

amphibious forces, though essential to an island landing, would also help

safeguard critical sea lanes during a blockade.

e most signicant Chinese military threat to Taiwan, as discussed in

many scholarly and media publications, remains a full invasion.

49

As Casey

demonstrates, the concepts for a landing are well established within PLA doc-

trinal writings. Numerous chapters in this volume, as discussed below, esh out

how various PLA forces and systems are being improved to tackle the challenges

of crossing the strait with sucient force, after attrition, to establish a foothold.

A question that has received much less attention is what comes next. Chinese

writings sometimes assume that any resistance would quickly collapse, though

as Sale Lilly points out, the PLA has increased urban warfare training, develop-

ing skills that could become relevant if Taiwan does not easily concede.

ird, the PLA is making wholesale changes to ready itself for higher

end Taiwan contingencies. Several chapters address the implications of re-

forms carried out during the Xi Jinping era. Conor Kennedy, Roderick Lee,

and Joshua Arostegui all highlight the conversion of pre-reform divisions into

brigades as a key part of the “below the neck” reforms that took place in 2017.

Kennedy notes that the PLA Army’s watercraft units, which complement the

navy’s sealift assets, have been “brigadized,” with newer ships coming online

to replace those of Cold War vintage. Lee sketches the PLAAF Airborne Corps’

transition from divisions to brigades, which increases those units’ maneuver-

ability, and catalogues their structure and hardware. Arostegui argues that

the army’s shift to a atter brigade structure encourages greater “initiative

and independence” for its six amphibious brigades. He also notes that the

relocation of forces has allowed for “improved mobilization timelines.”

Other chapters assess how the reforms generated a more cohesive “sys-

tem of systems,” bringing together the PLA’s diverse capabilities. Joel Wuthnow

argues that a joint command structure, modeled in part on the U.S. system,

18 Saunders and Wuthnow

allows theater commanders greater control over conventional forces while

strengthening the ability of the Central Military Commission to allocate “na-

tional assets,” such as the Strategic Support Force or long-range Rocket Force

conventional missiles that might be used for counterintervention purposes or

to deter other rivals during a Taiwan crisis. Chieh Chung describes a similar

centralization of PLA logistics forces, which are now better postured to allo-

cate and redeploy munitions and other supplies along an extended front. He

also provides a rare look inside China’s mobilization system, which has been

recongured so that multiple provinces—some of them far from the Taiwan

Strait—are mobilized to facilitate the ow of materiel during a conict.

Contributors also describe new hardware and equipment that would

allow the PLA to better execute its primary cross-strait operations. Ken-

nedy argues that the launch of multiple Type-075 large-deck amphibious

ships, which carry 30 helicopters, would increase the PLA’s ability to deliver

forces across the strait. His chapter also describes the potential enlistment

of civilian merchant ships, including high-capacity roll-on/roll-o vessels

and semi-submersible ships, to reduce the PLA’s sealift decit.

50

Arostegui

highlights new ZLT-05 amphibious ghting vehicles, whose 105-millimeter

assault guns will “improve commanders’ ability to direct res in optimal con-

ditions,” while Roderick Lee suggests that the new 4x4 tactical vehicles in the

PLAAF Airborne Corps will “improve the mobility and lethality of those units

equipped with [them].” No less important, Chieh Chung anticipates that lo-

gistics bases will soon be upgraded with specialized equipment to accelerate

the loading and unloading of supplies.

Fourth, despite recent reforms and new capabilities, the PLA continues

to wrestle with challenges in hardware, organization, training, and doctrine.

A common observation concerns insucient military air- and sealift to trans-

port multiple echelons of troops and equipment across the strait. Kennedy

describes the attention to civilian shipping as a response to insucient “gray

hull” sealift, though this approach raises questions about how well civil-

ian assets would perform in a combat environment. Kennedy also suggests

that dicult tidal conditions would reduce the utility of some of those as-

sets. Lee identies a similar shortfall of military airlift, which the PLA could

resolve by accelerating production of transport aircraft by 2030; the more

challenging problem is the limited capacity of mainland airelds to handle

Introduction 19

frequent sorties in a compressed timeframe. He also argues that the PLAAF

Airborne Corps will face dicult choices in how to employ those forces (such

as between oensive and defense ground operations). In the logistics arena,

Chung describes continuing constraints in warehouse capacity and medical

supplies, which could impede operations.

PLA reforms strengthened parts of the organizational structure but

might have created new weaknesses. Joshua Arostegui observes that the

army’s drive to emphasize combined arms battalions as the basic maneu-

ver unit could lead to overburdened command and sta at lower levels who

would be “faced with vulnerabilities resulting from networked command

and information systems; competing requirements from subordinate, lat-

eral, and higher units; and operations in a complex electromagnetic envi-

ronment.” He also notes that marine corps units remain nonstandardized

and thus less able to be plugged into an army-centric amphibious campaign.

Joel Wuthnow describes tensions in the joint command structure between a

recognition that commanders at the operational and tactical levels need to

be empowered to make dicult decisions and a simultaneous eort during

the Xi era to increase centralized decisionmaking and strengthen the role of

party committees throughout the PLA.

Authors also describe a variety of training and doctrinal impediments.

Sale Lilly notes that while the PLA has increased its urban warfare training, it

might have drawn the wrong lessons from U.S. experiences, highlighting the

allure of “decapitation strikes” and avoiding serious analysis of the drawn-out

insurgencies that U.S. forces faced in Afghanistan and Iraq. He concludes that

the PLA may be unprepared for a protracted resistance. e lack of combined

arms and joint training could also reduce the PLA’s battleeld eectiveness:

Arostegui notes that amphibious units rarely participate in opposition force

training, and older army watercraft units barely train at all, while Lee nds

that the PLAAF Airborne Corps has not conducted joint training (which

would be essential to support amphibious troops). Casey observes that PLA

doctrine has not been updated for over a decade, though a joint operations

outline approved by the Central Military Commission in November 2020

could set the stage for updated joint doctrine.

51

Finally, opportunities remain to strengthen Taiwan’s defense.

Wuthnow argues that the PLA’s Leninist organizational culture—which

20 Saunders and Wuthnow

emphasizes careful decisionmaking, along with a shift to a “system of

systems” architecture where the failure of a given system could have

broader implications for the cohesiveness of China’s military opera-

tions—supports operational concepts that confront PLA decisionmak-

ers with unforeseen and difficult-to-resolve dilemmas. This requires

precision-guided munitions combined with cyber and information op-

erations.

52

Chung similarly contends that Taiwan should target China’s

centralized logistics systems and networks to slow the PLA’s ability to

mobilize and sustain forces.

Several authors also encourage Taiwan to strengthen its asymmetric war-

ghting capabilities to deter or delay a PLA invasion. Casey suggests that lim-

ited sealift could require the PLA to focus its landing on just one part of the

island, which would allow Taiwan to concentrate its limited munitions. He also

argues that large amphibious ships, which could become high-value targets in

a cross-strait campaign, are better suited for global power projection opera-

tions. Kennedy suggests that Taiwan’s Overall Defense Concept, which prior-

itizes investments in antiship missiles, could exacerbate PLA concerns about

the likely attrition of its amphibious forces and therefore enhance deterrence.

Drew ompson notes that Taiwan has either built or procured several key sys-

tems associated with the concept, including modern sea mines, fast attack ves-

sels, Harpoon coastal defense missiles, howitzers, and Stinger missiles.

Nevertheless, Taiwan’s defenses remain troubled by factors beyond

China’s military threat. According to Huang, domestic problems include re-

cruitment shortfalls as Taiwan shifts to an all-volunteer force, the need to

maintain expensive legacy systems that have less utility in a war, such as

ghters and large surface ships, and a population that has trouble “imagin-

ing an actual war.” He also worries that the Overall Defense Concept’s sin-

gular focus on preparing for invasion could leave Taiwan less well-prepared

for gray zone coercion and other problems, such as a blockade. ompson

argues that while Taiwan has made progress in hardware, it needs to focus

more on personnel issues, including strengthening the reserve force and on

stockpiling critical supplies to weather a blockade. Huang and ompson

both argue that U.S. and Taiwan defense establishments could work to im-

prove Taiwan’s posture, though progress requires a higher level of political

and scal commitment from Taiwan.

Introduction 21

Outline of the Book

is edited volume is divided into four parts. e rst considers the political

and strategic calculus informing Chinese decisions toward Taiwan. In chap-

ter 1, Phillip Saunders evaluates three logics underlying Beijing’s choices over

the past three decades—what he terms leverage, united front, and persuasion.

He argues that authoritarian political trends in China; sharply declining sup-

port for unication in Taiwan, driven in part by the cautionary example of

Hong Kong; and shifts in Taiwan’s domestic politics have reduced the viabil-

ity of a conciliatory path to unication and increased Beijing’s focus on more

coercive tools. In chapter 2, Andrew Scobell suggests that China’s calculus

on the costs, risks, and benets of using force will be shaped by the country’s

trajectory. He describes four scenarios, arguing that Beijing would likely be

most war-prone in an “ascendant” future, where Taiwan remains a singular

obstacle to national greatness, or in an “imploding” future, where the Chi-

nese Communist Party bets its future on a risky conict.

e second part of this volume explores Chinese military options along

the spectrum of conict. Mathieu Duchâtel considers gray zone tactics below

the level of armed conict in chapter 3. He explains why military and political

factors could lead Beijing to move beyond its recent expansion of coercive

operations in Taiwan’s Air Defense Identication Zone and consider even

more provocative moves, including incursions into Taiwan’s territorial seas

and airspace, an intensied cyber campaign, or the seizure of one of Taiwan’s

key oshore islands. Such actions, despite their risks, could be seen as useful

in manufacturing a “series of crises” that demonstrate resolve while creating

a pretext for escalation above the gray zone.

e following chapters explore how PLA combat operations across the

Taiwan Strait might unfold. In chapter 4, Michael Casey details the three pri-

mary cross-strait campaigns discussed in PLA doctrinal writings: joint re-

power strike, joint blockade, and joint island landing. For each campaign,

Casey describes PLA assessments of critical decision points, operational

phasing, and military requirements, while also relaying how Chinese writings

discuss the task of countering U.S. or other foreign intervention. In chapter

5, Sale Lilly addresses how the PLA is preparing for resistance on the island

in the post-landing phase of an invasion. He documents more frequent PLA

22 Saunders and Wuthnow

urban warfare training over the last decade, though he suggests that PLA au-

thors, inuenced by the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003, may be overly opti-

mistic about the chance of a quick victory.

e third part of this volume dives deeper into specic Chinese forces and

systems that would be critical to a cross-strait campaign, beginning with the

landing forces. In chapter 6, Joshua Arostegui describes the structure of the PLA’s

amphibious units. He argues that a recent shift from divisions to brigades im-

proved the PLA’s ability to conduct a blockade or a landing, though inadequate

sealift means that these forces are likely most useful in the near term in deterring

Taiwan independence through exercises held on the mainland. Arostegui also

explains the division of labor between the army, whose six amphibious brigades

are focused on cross-strait operations, and the PLA Navy Marine Corps, which

prepares for more diverse missions. In chapter 7, Roderick Lee sketches the

composition of the PLA’s airborne forces. He explains how the reformed PLAAF

Airborne Corps would be instrumental in an island seizure, though he identies

limited airlift, airport capacity, and training as possible constraints.

Another pair of chapters looks more closely at PLA logistics require-

ments. Conor Kennedy, in chapter 8, argues that the PLA might address a

shortfall in military sealift by using civilian merchant ships to ferry some

troops and equipment across the Taiwan Strait. Reviewing Chinese technical

publications, he nds that the PLA is exploring how forces could be moved

ashore both with and without an operational port. In the latter case, there

are signs that the PLA is investigating how to use articial harbors, like the

Mulberry harbors used in the Normandy invasion. In chapter 9, Chieh Chung

describes the PLA’s new logistics structure and catalogues its prodigious lo-

gistics needs for a cross-strait campaign in three areas: materiel, medical

support, and transportation. He also explains how recent improvements in

China’s mobilization system could lead to a more ecient transition of soci-

ety from a peacetime to a wartime footing.

Chapter 10 by Joel Wuthnow discusses how reforms have created a com-

mand structure better suited to joint operations. In the Taiwan context, the

Eastern eater Command conducts contingency planning and joint train-

ing in peacetime and would oversee ground, naval, and air forces during a

campaign. Nevertheless, the command structure remains prone to problems

of centralized or consensus-oriented decisionmaking and other issues that

Introduction 23

could reduce the eectiveness of PLA operations. He suggests that Taiwan

and the United States could exploit these problems during a crisis through

rapid and hard-to-predict operations that force overwhelmed leaders to

make dicult decisions under strenuous circumstances.

e nal part of this volume focuses on improving Taiwan’s defenses. In

chapter 11, Alexander Chieh-cheng Huang argues that the Overall Defense

Concept has shown promise in positioning Taiwan to withstand a PLA landing

but is less useful in countering Chinese gray zone coercion or other PLA combat

operations, such as a blockade. He recommends a renement of the concept,

underwritten by a consensus that needs to be strengthened across Taiwan’s

political landscape. In the nal chapter, Drew ompson considers the capa-

bilities needed to prevail in the ght “Taiwan cannot aord to lose,” suggesting

that Taiwan should continue to develop its asymmetric approaches, giving more

attention to personnel and logistics issues. He also suggests ways to strengthen

U.S.-Taiwan defense cooperation, including more intensive bilateral planning

and integration of Taiwan’s sensors with U.S. stando strike weapons.

Conclusion

e analysis in this volume suggests that the PLA already has the capability to

apply low-level coercive pressure and conduct air and missile strikes against

Taiwan. e PLA likely also has the capability to execute a blockade absent

U.S. intervention. However, these military options would leave the sitting Tai-

wan government intact, would provide time for U.S. forces to intervene, and

would likely entail considerable diplomatic, economic, and military costs in

addition to the risk of escalation into a major war with the United States.

A cross-strait invasion could potentially be decisive but probably lies be-

yond current PLA capabilities given known gaps in airlift, sealift, and logis-

tics, as well as other limitations identied by the contributors to this volume.

e PLA is working hard to improve its capabilities and rectify its shortfalls.

However, the U.S. and Taiwan militaries are also improving their capabilities,

including by acquiring new weapons, developing new operational concepts,

and improving ghting eectiveness in confronting the PLA. e PLA has

made considerable progress over the last 20 years in building the capabilities

necessary for an invasion and in closing the qualitative gap with the U.S. mil-

itary, but future progress is not guaranteed.

24 Saunders and Wuthnow

A full assessment of CCP decisionmaking about Taiwan must include

both costs and risks.

53

Costs are the known diplomatic, military, and eco-

nomic losses that CCP leaders would expect if they decided to use force to try

to resolve the issue of Taiwan’s status. Risks include estimates of additional

costs that China might have to pay depending on how the conict unfolds.

ese could be calculated by multiplying the potential additional costs by

the probability that China would ultimately have to pay them. ese costs

and risks could potentially be assessed by outside analysts, but, ultimately,

it is the subjective assessments of CCP and PLA leaders that matter most.

54

e operational challenges the Russian military encountered in its invasion

of Ukraine and the political and economic sanctions imposed on Moscow

following the invasion will likely cause Chinese leaders to increase their esti-

mates of the possible costs and risks of taking military action against Taiwan.

Within the military sphere, there are considerable uncertainties in as-

sessing how a military conict might play out. If the United States does not

intervene and Taiwan’s will to resist collapses quickly, China might achieve

its political goals at a lower-than-expected cost without having to execute

an invasion. However, Chinese leaders cannot assume this outcome and

would have to be prepared for less favorable results, including sti Taiwan

resistance and rapid U.S. intervention. As this volume discusses, the PLA

currently has specic capability gaps that hinder its ability to successful-

ly execute an invasion. e PLA also has broader weaknesses, including

in senior leadership command ability, limited experience with conduct-

ing integrated joint operations, and lack of combat experience. Moreover,

there are no real-world examples of advanced militaries using the full suite

of advanced information-warfare capabilities against equally capable

adversaries; neither are there examples of two nuclear-armed countries

ghting a major war against each other. e diculty of assessing the like-

ly outcome of a military conict—and the high costs of protracted war or

nuclear escalation—will give leaders in China and the United States strong

incentives to try to avoid a conict.

Moreover, there are considerable nonmilitary costs and risks that ex-

tend beyond the correlation of forces. In the case of a U.S.-China conict

over Taiwan, PRC risks include a military failure that might jeopardize the

political survival of top CCP leaders, the potential for a protracted war that

Introduction 25

threatens China’s economy and political stability, and a postwar situation

with a powerful and hostile United States and other countries more willing

to participate in an anti-China coalition. ese costs might occur even if the

PLA successfully achieves its operational objectives. If the PLA continues to

make up ground in its military modernization, deterrence might rest more

heavily on these nonmilitary factors.

CCP statements that China would prefer to pursue peaceful unication

with Taiwan are logical considering the high costs and risks of resolving the

issue with force.

55

is highlights the need for greater attention to the politi-

cal foundations of cross-strait relations and of U.S.-China relations. As noted

above, neither China, nor Taiwan, nor the United States is fully satised with

the current framework of cross-strait relations. Nevertheless, this framework

has met the minimal requirements of all three sides for more than 40 years.

For this situation to continue, restraint and political creativity will be nec-

essary on all sides. Beijing will need to continue to reemphasize its objective of

peaceful unication and nd creative ways to move beyond the “one country,

two systems” framework that has little appeal on Taiwan. is will require rec-

ognizing the high costs and risks of seeking a military solution and that eorts

to achieve a decisive military force advantage will have extremely negative ef-

fects on U.S.-China relations and on regional stability, which in turn will aect

China’s economy and domestic stability. Even in the absence of a conict, the

costs of seeking PRC military superiority are likely to continue to rise.

Taiwan leaders will need to acknowledge the high risks of not only for-

mally declaring independence but also of foreclosing the possibility of uni-

cation at some future date under more favorable circumstances. Such

restraint would likely be necessary to maintain U.S. support, which is critical

if Taiwan is to maintain its current de facto sovereignty in the face of China’s

power advantage. Although heightened U.S.-China strategic competition has

created new opportunities for Taiwan to improve relations with Washington,

more adversarial U.S.-China relations that include signicant economic de-

coupling would have negative consequences for cross-strait relations. Taiwan

leaders might ultimately have to consider whether a negotiated political ar-

rangement that preserves much of Taiwan’s current de facto sovereignty is

preferrable to a hostile relationship with China that damages Taiwan’s econ-

omy and security environment.

56

26 Saunders and Wuthnow

Washington will need to not only weigh its stakes and obligations to Tai-

wan but also consider its obligations under the communiqués that it signed

with China as part of normalizing relations. Recent years have seen a steady

blossoming of the relationship between the U.S. and Taiwan governments

and of that between the U.S. and Taiwan militaries. Beijing opposes any in-

crease in U.S.-Taiwan cooperation, but developments that further erode U.S.

“one China” commitments could prompt China to take limited military ac-

tion to reestablish limits on unocial U.S. relations with Taiwan. e United

States has historically focused on encouraging a peaceful, noncoercive envi-

ronment for cross-strait relations rather than pursuing a specic resolution of

Taiwan’s status. e United States should continue that policy and not adopt

a policy of preventing unication.

If Chinese leaders conclude that the prospects of peaceful unica-

tion have disappeared, then the potential for war over Taiwan—despite its

known high costs and unfathomable risks—would increase dramatically.

e United States must be careful that actions intended to deter a conict

do not end up precipitating one.

Notes

1

“Full Text of Xi Jinping’s Report at 19

th

CPC National Congress,” Xinhua, October 18,

2017, available at <http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/special/2017-11/03/c_136725942.htm>.

2

At the time, the Republic of China (ROC) government also asserted that Taiwan was an

integral part of China.

3

For a concise overview of the Taiwan Relations Act and U.S. policy, see Richard C. Bush,

A One-China Policy Primer, East Asia Policy Paper 10 (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution,