Housing South Bend:

Opportunities for

transformative investment

Photo courtesy of City of South Bend, Indiana Department of Community Investment

© October 2022

This report was commissioned by the City of South Bend, Indiana, and was conducted

by the Kinder Institute for Urban Research at Rice University.

Acknowledgements

Kinder Institute for Urban Research

Stephen Averill Sherman

William Fulton

City of South Bend, Indiana Department of Community Investment

Elizabeth Maradik

Caleb Bauer

Santiago Garces

The Kinder Institute is an interdisciplinary research organization at Rice University in Houston. The institute works in direct partnership with

agencies and organizations that can use its research, data and policy analysis in meaningful ways to implement solutions to critical challenges.

Its research agenda is jointly developed with these partners and addresses the intersecting issues of housing, education, economic mobility,

health and population research.

Housing South Bend: Opportunities for transformative investment

Executive Summary

Through the American Rescue Plan Act , the city of

South Bend has $6 million to spend on housing.

! In early 2021, the Biden administration signed

the American Rescue Plan Act , or “ARP”. The law

allocated billions of dollars to local governments

for many different projects, including affordable

housing. Of the city’s $45.2 million ARP allocation

for Fiscal Year 2022, $6 million is devoted to “safe,

affordable housing.” To earn maximum leverage from

the investment, the city asked the Kinder Institute

for Urban Research (KIUR) to perform an analysis

on its existing housing market and empower the

city with data to inform its funding options.

— Part of this project also entailed KIUR hearing

input from South Bend stakeholders in the city

government, not-for-profit affordable housing

development, for-profit home construction, and

property management sectors during two site

visits in December 2021 and April 2022.

South Bend’s homeownership aordability

challenges are multifaceted.

! According to multiple listing service (MLS) data on

home sales from 2016 to May 2021, nearly every

single census tract in South Bend has a significant

gap between the hypothetical cost of constructing a

new home and the average sales price in that census

tract. This is referred to as the “appraisal gap” in

this report. This widespread gap suggests that

local homebuilders may be timid about building in

central city tracts, and instead choose to build in

South Bend’s growing suburbs.

! Additionally, a newly built home with a sales

price of $200,000, which is the estimated cost of

construction, is unaffordable to most South Bend

residents. Estimated monthly mortgage costs would

be $1,297

1

, which is beyond the 30% monthly

income affordability threshold of a household

earning the city’s 2019 median household income

(MHI), $40,265.

! Yet in most census tracts, the average sales price of

an existing home was within reach of a household

earning the tract’s median income. Between 2016

and mid-2021, the average home sales price citywide

was $104,106.

2

With a conventional Fair Housing

Administration (FHA) loan, estimated monthly

costs would be $757, a sum that is within the

30% affordability threshold of South Bend’s MHI.

Many neighborhoods have much lower sales prices

than $104,106, with seven census tracts having

extremely low mean sales prices below $50,000.

! Such statements about local home affordability do

not take into account home quality. Regarding quality,

many homes are older and in need of significant

rehabilitation, and a “down-to-the-studs” renewal

of an older home is often in excess of $100,000,

which is close to the city’s mean sales price.

— While not a citywide survey of home quality,

South Bend’s high vacancy numbers suggest

many homes are in need of repair. As of

the 2019 American Community Survey, an

estimated 21% of the city’s housing units are

vacant, while the most recent U.S. Postal Service

vacancy data shows 3,569 residential addresses

vacant in the city. Statements about home

1 This assumes a 3.5% down payment, a 4.5% yearly mortgage

interest rate paid monthly, 1% property taxes, 1% home

insurance, and 0.85% private mortgage insurance. Notably,

this estimate does not account for upkeep or utilities. These

assumptions are standard for monthly housing costs.

2 Unless otherwise mentioned, all sales price figures are only for

traditional or private sales, as marked in MLS data, and inflation-

adjusted to 2021 dollars.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Rice University Kinder Institute for Urban Research

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Appraisal Gap in South Bend

Housing South Bend: Opportunities for transformative investment

affordability in South Bend also do not address

many well-documented personal and structural

barriers to homeownership in the United States.

! Stakeholder engagement highlighted the need for

high-quality “comp” houses to improve the local

housing market.

— Without prompting, all of these diverse

stakeholders, despite having different

perspectives on South Bend’s housing system,

broached the challenge of securing higher-value

home appraisals. The depressed housing market

in certain neighborhoods entails that even when

people want to buy within these neighborhoods,

low appraisals make it more difficult to secure a

loan. A below-sales-price appraisal means that

the borrower has to provide up-front cash to

make up the difference between the (higher) sales

price and the (lower) appraisal value. This is a

large and common barrier to home purchases.

While South Bend’s rent is lower than most larger

cities’, many residents still cannot aord it.

! Overall, the city’s median rent is $854, which is

affordable for a household earning the city’s median

income of $40,265. In 10 of the city’s 43 census

tracts, rents are higher than 30% of that tract’s

monthly median household income, signaling that

they are not affordable. For example, Tract 17 has

a median rent of $575—much lower than the city’s

median—but a household earning the tract’s MHI

can only afford rent up to $480 per month.

There is an under-supply of aordable housing for

lower-earning South Bend residents.

! Households on the lowest end of the income

spectrum are the most squeezed. Per 2019 American

Community Survey numbers, households earning less

than $15,000 per year make up 18% of the city, but

only 11% of the housing stock is affordable to these

households. These households are forced to spend

more on housing, while also competing for housing

with families who are earning more. In addition,

there are downward pressures on the housing market,

as an under-supply of more expensive homes means

wealthy households in South Bend are consuming

part of the housing supply that would be affordable

and otherwise available to earners at or around the

city’s median household income.

ARP funds alone can’t solve all of the city’s

aordable housing challenges, but they can make

a dierence on a smaller scale.

! The city’s ARP allocation for affordable housing in

the 2022 budget is $6 million. Allocations in this

report target $5.5 million to account for potential

cost overflows.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Housing supply and demand by household income bracket

(For a detailed methodology, see Ch. 1). Source: ACS 5-year survey 2019

!

0 2,000 4,000 6,000 8,000 10,000 12,000

Less than $15,000

$15,000 - $24,999

$25,000 - $49,999

$50,000 - $74,999

$75,000 - $99,999

$100,000 - $149,999

$150,000 or more

Demand (no. of households in income bracket) Supply (no. of housing units aordable within that income bracket)

Rice University Kinder Institute for Urban Research

! The $5.5 million can have an important yet limited

impact.

— It cannot enable a down-to-the-studs renewal of

the city’s 3,000+ vacant properties.

— Within budget, ARP funds can help enable

building around 50 housing units—either

apartment units or standalone homes—while

the city has a roughly 2,500 housing unit supply

shortage for its lowest-income residents.

! 150 bedrooms in 50-something new homes may

not have a visible, noticeable effect if disbursed

evenly across the city, but they can have a visible

effect on a smaller neighborhood. Additionally,

large-scale development on a large vacant parcel

can enable economies of scale for homebuilders,

minimizing costs.

South Bend planning sta and researchers

deliberated and vetted three scenarios for

how the ARP money could be spent.

! These ARP allocation scenarios were not plans

to allocate funds, but were designed to investigate

and explore the future effects of potential ARP

investment decisions.

! To aid in scenario creation, researchers developed

a pro forma model, similar to one used within the

real estate industry, to estimate how much housing

the ARP allocation could build or renovate. The

model used defensible assumptions for financing,

interest rates, construction costs, and monthly

affordable housing costs. This exercise assumed

ARP funds would be used mostly as down payments

for construction loans or rehabilitation.

! There were some key challenges and points

identified from the scenarios.

— Building housing for the lower-earning residents

means that, generally, less housing can be

built. More subsidy is needed for a larger down

payment to assure monthly construction

loan repayment costs are within the monthly

affordability means of these residents. This

means more money gets spent up front on a

down payment, and therefore the ARP subsidy

cannot help build as many units.

— Outside equity can help leverage the ARP

allocation to build more affordable rental

homes, which raises the importance of securing

outside funds.

— A mix of market rate and affordable units can

help a low-income rental development be more

financially viable, since rent from market-rate

units help meet loan servicing costs.

— Vetting the scenarios helped improve the draft

pro forma model.

! Findings from this investigation helped inform the

recommended options presented in the final chapter.

A key choice for decision-makers is whether to

spread the ARP allocation or go “all in.”

! Using the lessons from the scenario-building

process, and employing an improved pro forma

tool, this report concludes with three recommended

options for the ARP funds.

— One is called “a little bit of everything” which

adds 142 bedrooms and has a mix of very

affordable rental housing, moderately affordable

owner-occupied housing, and rehabilitation

funds, which are not accounted for in the

additional bedroom count. The majority of

bedrooms are in standalone single-family homes.

— The second is called “go all in,” and attempts

to build as much extremely affordable rental

housing as possible (144 bedrooms total,

predominately in two-bedroom sixplex units as

this was the most cost-effective option).

— The third is to “stick to the budget,” which follows

the 2022 proposed budget for the allocation.

! South Bend has existing neighborhood plans

that could provide useful insights in spending

the ARP funds. Prior plans may identify useful

sites for ARP-funded housing developments.

For example, the Lincoln Park neighborhood

plan identifies “neighborhood nodes,” or central

points within the neighborhood that can be focal

points for regeneration. Additionally, the Vacant

and Abandoned Properties Task Force Report from

2013 divides the city in the four different types

of real estate markets, each of which has unique

challenges. For example, city decision-makers

may choose to invest only in “revitalization” or

“reinvestment” areas, per that plan.

! Other final recommendations include exploring

rent-to-own programs for the properties that are

built and taking measures to ensure affordable

owner-occupied homes built through this program

are not quickly used for profit.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Housing South Bend: Opportunities for transformative investment

Background

The Biden administration passed the American Rescue

Plan Act (ARP) in March 2021, which sought to stimu-

late the economy in COVID-19’s wake. The act, which

most notably authorized $1,200 stimulus payments

to qualifying individuals, also allocated $65.1 billion

to local governments, of which South Bend received

$45.2 million. South Bend allocated $6 million for

housing—housing financing, housing repair, and home

buying assistance—without estimating specific targets

or tranches.

To inform how they allocate funds, City of South Bend

officials contracted with the Kinder Institute for Urban

Research (KIUR) at Rice University in Houston, Texas.

This study represents the findings from this joint re-

search project.

For Phase 1, researchers assembled diverse data

sources to describe South Bend’s housing system: its

markets, affordability (or lack thereof), vacancy, and

home quality.

A second key data source came from stakeholder input.

Roughly 20 local stakeholders outside of the city gov-

ernment were consulted in December 2021 by KIUR

and city staff. These representatives from community

groups, the for-profit real estate industry, the housing

finance sector, and the nonprofit affordable housing

sector all provided insight to the challenges of South

Bend’s housing sector.

Key challenges identified from stakeholder interviews

included securing favorable appraisals, securing

mortgages for lower-income buyers, and managing

high-quality yet affordable rental properties.

In Phase 2, a cost- and revenue-calculating model was

created to help estimate how far the city’s ARP funds

could go in building and renovating affordable housing,

specifically by helping close the gap between construc-

tion costs and what South Bend residents can afford.

The resulting product, which was similar to a pro forma

model typically used in the real-estate development sec-

tor, showed how many units could be built according to

different affordability estimates (i.e., if they are afford-

able to households which have “extremely low incomes,”

“very low incomes” or “low incomes”, defined as 30%,

50%, or 80% of the area’s median income, respectively).

This pro-forma model revealed the tradeoffs South

Bend faces in spending the ARP housing money.

For example, building units that would be affordable

to extremely low-income South Bend residents would

entail spending more ARP funds per unit, because more

ARP funds would be needed to close the gap between

construction costs and what a resident could afford.

Fewer units could be built overall.

On the other hand, the ARP allocation could help build

more units if the units were affordable for low-income

or very low-income residents. This choice risks leaving

behind the lowest earning South Bend residents and

communities. Chapter 2 describes these tradeoffs, and

others, indepth.

These tradeoffs were central to the development scenar-

io exercise completed in March 2022. For that exercise,

project staff used the pro forma model to create three

different scenarios for how the ARP funds could be

spent on housing.

Creating the scenarios achieved three purposes. First,

presenting hypothetical development scenarios to

city staff brought to the forefront certain barriers to

proposed projects, such as available land, or overhead

costs for rehabilitation. Second, the scenarios helped

determine just how much housing could be built with

Introduction

INTRODUCTION

Rice University Kinder Institute for Urban Research

the ARP funds, which helped city decision-makers un-

derstand the scope and potential for the investment.

Third, the scenario development process helped hone

the pro forma model, ensuring that the most useful

feasible tool would be delivered to the city at the end

of this study.

The scenarios developed and included in this report

were shared with South Bend staff in March 2022.

Phase 3 was the culmination of this report, employing

findings from the scenarios to present options for how

the money could be spent.

These recommended options are not explicit instruc-

tions to invest in certain South Bend communities over

others. Rather, they are proposals for spending the ARP

allocation, and make explicit the tradeoffs involved

with certain investment decisions.

One recommended option is to “go all in”, using the

funds to subsidize a developer to build a larger-scale

extremely affordable housing development on a single

site with ample vacant land.

Another recommended option is “a little bit of every-

thing” subsidizing a developer to build a variety of

affordable housing at different affordability levels in

smaller, scattered parcels.

Finally, a third recommended option is to “stick to the

budget,” which describes a plan that follows the city’s

2022 proposed budget for the ARP fund allocation.

As the city finalizes its decision, South Bend sits on

many valuable neighborhood plans that have been writ-

ten in the last decade, and staff are strongly encouraged

to consult prior neighborhood plans in order to identify

sites for investment.

Photo courtesy of City of South Bend, Indiana Department of Community Investment

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Housing South Bend: Opportunities for transformative investment

Summary

The cost of buying an existing home and the

cost of building a new home in South Bend

are dierent, with new construction being

unaordable to many residents.

! In almost every single census tract in the city, a

median-income-earning household can afford to

buy an existing home.

— A house is considered “affordable” if monthly

costs are less than 30% of the geography’s

monthly median household income (MHI).

— Many South Bend homes are older, which

contributes to lower prices.

! In contrast, for most neighborhoods, new home

construction costs are much higher than the

average home sales price, which disincentivizes

builders from building in these places. This gap is

called the “appraisal gap” in this report.

! Buying a newly constructed home—potentially

costing about $200,000—is out of reach for median

income households in every South Bend census

tract but one.

Even in neighborhoods with very low rents (<$600),

many residents still cannot aord a lease.

! In about one quarter of South Bend census tracts

(10 of 43), rent exceeds 30% of the tract’s monthly

MHI. These tracts are geographically concentrated

south and west of downtown.

There is unmet demand for homes.

! Existing market studies estimate that many of

South Bend’s central neighborhoods can absorb

around 2,000-2,500 new units over a 5-year period.

! Despite this demand, only 121 of the roughly 6,000

home sales since 2016 have been for homes built in

the past decade.

! Currently, the largest under-supply of homes is for

the lowest-earning households and highest-earning

households.

There are some (cautiously) positive signs

for the future:

! Trends point to increased sales prices:

— While the foreclosure crisis hit South Bend

particularly hard, home prices have mostly

recovered since the Great Recession, with the

exception of certain western neighborhoods.

— COVID-19 has increased home sales prices.

— While good for building equity, and the ability

to build more units, increasing prices may risk

putting home ownership out of reach for some

South Bend residents.

! Vacancy appears to be decreasing in many

challenged neighborhoods.

Another positive sign: Prior plans and market

studies evidence that South Bend has strong

housing demand.

! Neighborhood plans, produced by city planning

staff, identify areas of potentially transformative

investments within certain South Bend

neighborhoods.

Chapter 1:

Existing Conditions: South

Bend’s housing is inexpensive

yet out-of-reach for many

CHAPTER 1: EXISTING CONDITIONS: SOUTH BEND’S HOUSING IS INEXPENSIVE YET OUTOFREACH FOR MANY

Rice University Kinder Institute for Urban Research

Understanding the gaps: South Bend

home prices, home aordability, and home

construction costs

Homeownership and home sales

One of the central challenges of South Bend’s housing

market, which is shared by other Rust Belt cities, is

that many for-profit homebuilders decide not to invest

in central city neighborhoods. Low home sales prices

suggest a depressed local market, which discourages

homebuilders from making an investment.

The first question to answer: What exactly is the going

price for a home in South Bend across its many neigh-

borhoods?

The citywide average single-family home sales price, us-

ing data from 2016 through May 2021, was $104,106

(inflation-adjusted to 2021 dollars).

This price reflects the average of 5,998 home sales

from that period, only for sales marked “traditional”

or “private” in Multiple Listing Services (MLS) data,

which excludes the roughly 600 foreclosure sales,

trades, estate settlements, auctions, and other less

common property transfer types from the same period.

All home sales for less than $100 were also eliminated.

This analysis only includes sales on parcels marked as

“residential one-family dwelling on a platted lot” within

local assessor records, eliminating sales on commercial,

industrial, or multifamily properties.

In many neighborhoods west of the river, homes sell for

less than $50,000, and citywide home prices are mostly

around $100,000. When compared to sales costs in larg-

er metros like Chicago or Houston, these prices are low.

Can South Bend residents afford a home in their city?

In most neighborhoods, they can.

The homeownership affordability gap is calculated by

estimating monthly housing costs for the average home

sales price in each census tract, and comparing these

estimates to the MHI for that tract.

3

Figure 2 shows that

across the city (except in some central areas), residents

can afford to buy homes in their neighborhood. This

is largely because in many parts of the city, an average

home costs less than $100,000.

This map, and the finding that most homes are theoret-

ically affordable to South Bend residents, omits certain

important factors. First, while someone’s income is

within the affordability threshold, homeownership

may be out of reach because of personal and structural

factors, including unstable work histories caused by

deindustrialization, or racial/ethnic inter-generation-

al wealth disparities influenced by past racist lending

practices, among other reasons. These factors shape a

person’s ability to have a good credit score, build sav-

ings for a down payment, or have funds for future home

repairs. Each of these factors can affect the likelihood a

bank will issue a mortgage.

Second, being able to afford a home is not the same as

being able to afford a higher quality home. Low initial

home prices may mask a home’s need for repairs, mak-

ing the true cost of buying the home much higher than

the price suggests.

Given the relative affordability of existing homes, but

unknown costs of necessary repairs, another way to

think about housing in South Bend is to ask if residents

can afford a newly constructed home.

A different affordability gap calculation can help

answer this question by taking the difference between

what a household earning the median household in-

come could afford and the estimated monthly housing

costs on a hypothetical $200,000 new home (which

is the estimated construction cost for a home within a

larger subdivision).

The results of this calculation show median earner

South Bend residents cannot afford newly construct-

ed homes. The estimated monthly housing costs for a

3 A detailed methodology: Housing is considered affordable

when it costs less than 30% of monthly income. To determine

tract-specific affordability, first, each census tracts 30% median

household income (MHI) was calculated. Next, monthly housing

costs were taken from the tract’s mean home sales price (source:

MLS data) with the assumption that a buyer purchasing that

house had a 4.5% yearly mortgage interest rate, property

insurance and tax rates at 1% of home value, a mortgage

insurance rate at 0.85%, and a 3.5% down payment (per FHA

regulations). The difference between these estimated monthly

housing costs, and 30% of monthly income based on the tract’s

MHI, is the affordability gap. This calculation does not account

for upkeep or utilities costs.

CHAPTER 1: EXISTING CONDITIONS: SOUTH BEND’S HOUSING IS INEXPENSIVE YET OUTOFREACH FOR MANY

Housing South Bend: Opportunities for transformative investment

CHAPTER 1: EXISTING CONDITIONS: SOUTH BEND’S HOUSING IS INEXPENSIVE YET OUTOFREACH FOR MANY

FIGURE 1

Home sales prices and volumes by census tract

Rice University Kinder Institute for Urban Research

$200,000 home ($1,452) exceeds what a local medi-

an-income earner can afford ($1,006). Even when look-

ing at differences in earnings across the city’s neighbor-

hoods, only a few can afford a newly constructed home

at $200,000. For a hypothetical newly constructed

home, many South Bend residents find themselves

priced out of ownership.

The affordability gap for new home construction

throughout most of the city has led some for-profit build-

ers to infer that few local buyers exist despite the market

studies cited later, which show demand for new homes.

Location is essential to how appraisers value homes,

and neighborhood-level home markets help inform the

decision to site new construction. Thus, in addition to

calculating the gap between what residents can afford

and the cost of a new home, it is also valuable to calcu-

late the gap between prices on the existing home market

and the cost of a new home.

The difference between home construction costs and

existing home sales prices in South Bend’s census tracts

is referred to as the “appraisal gap.” Displaying the

appraisal gap shows the difference between current

housing prices and construction costs, and helps policy-

makers and the public understand the scale of the sub-

sidy needed to incentivize new home construction. The

appraisal gap also provides an estimate of how much

current homeowners could invest in renovations before

the purchase of a new home would be the more econom-

ical choice. In this way, the appraisal gap can also guide

decisions on how much could be put toward rehabilita-

tion subsidies from the ARP funds. An important caveat

is that the dollars put into a renovation do not equal the

dollars added to that home’s value, particularly within

weaker housing submarkets. Lastly, displaying the gap

can help residents understand the general price dif-

ferences between new construction and existing sales

prices at the neighborhood scale.

An appraisal gap exists throughout most of South

Bend’s neighborhoods, with the largest gaps in the cen-

tral and western neighborhoods of the city (Figure 4).

Appraisal gaps were calculated with sales data through

May 2021. This analysis does not reflect continued in-

creases in home sales prices that occurred more recent-

ly. As a result, the appraisal gap in South Bend is likely

smaller now (Fall 2022), but at the same time, South

Bend’s affordability gap has likely increased.

Home renting and renters’ aordability

The prior affordability analysis focuses on the home-

ownership market. However, roughly 40% of South

Bend households are renters.

South Bend follows a common trend: renters occupy a

larger share of the households in the urban core, while

homeowners dominate the suburbs (Figure 5). However,

South Bend has a large “middle” between the inner- and

outer-city where there is not a clear majority of renters

or homeowners. Even some of the areas near Notre

Dame’s campus still have many owner-occupied hous-

ing units. In these and other older neighborhoods, zon-

ing largely exists to support diverse infill housing stock.

Higher-rent areas are common east of the river, partic-

ularly near campus (Figure 6). High-rent communities

can also be found in the southeast and west, including

the less wealthy Southeast and Lincoln Bendix neigh-

borhood areas. Despite some areas having higher rent,

most tracts throughout the city do not have an afford-

ability gap for renters (Figure 7). The affordability gap

for renters is the difference between 30% of a tract’s

median household income and that tract’s median rent.

Still, there are some areas with large affordability gaps,

even in areas where the median rent is relatively low.

For example, the tract containing the St. Casimir neigh-

borhood (Tract 27)

4

has a median rent of $826 (lower

than the citywide median of $851), but there is still a

large affordability gap in this neighborhood because of

the lower incomes of its residents.

Some neighborhoods have high rents but relatively low

home sales values. For example, the tracts containing

some southeastern neighborhoods and parts of Lincoln-

Bendix and Kennedy Park have relatively high rents

(more than $900) but relatively affordable homes (less

than $50,000, per Figure 3). For these neighborhoods,

rent is more than the cost of a mortgage.

4 For more information on census tracts, see St Joseph County GIS:

https://sjcgis-stjocogis.hub.arcgis.com/

CHAPTER 1: EXISTING CONDITIONS: SOUTH BEND’S HOUSING IS INEXPENSIVE YET OUTOFREACH FOR MANY

Housing South Bend: Opportunities for transformative investment

Appraisal Gap in South Bend

FIGURE 2

Ownership affordability gap by census tract

CHAPTER 1: EXISTING CONDITIONS: SOUTH BEND’S HOUSING IS INEXPENSIVE YET OUTOFREACH FOR MANY

Rice University Kinder Institute for Urban Research

FIGURE 3

Affordability gap for newly constructed $200,000 home by census tract

CHAPTER 1: EXISTING CONDITIONS: SOUTH BEND’S HOUSING IS INEXPENSIVE YET OUTOFREACH FOR MANY

Housing South Bend: Opportunities for transformative investment

Appraisal Gap in South Bend

FIGURE 4

Appraisal gap: Difference between new construction costs

and existing home sales prices by census tract

CHAPTER 1: EXISTING CONDITIONS: SOUTH BEND’S HOUSING IS INEXPENSIVE YET OUTOFREACH FOR MANY

Rice University Kinder Institute for Urban Research

FIGURE 5

Predominant housing tenure type (owner/renter) by census tract

CHAPTER 1: EXISTING CONDITIONS: SOUTH BEND’S HOUSING IS INEXPENSIVE YET OUTOFREACH FOR MANY

Housing South Bend: Opportunities for transformative investment

FIGURE 6

Median rent by census tract

CHAPTER 1: EXISTING CONDITIONS: SOUTH BEND’S HOUSING IS INEXPENSIVE YET OUTOFREACH FOR MANY

Rice University Kinder Institute for Urban Research

FIGURE 7

Renter affordability gap by census tract

CHAPTER 1: EXISTING CONDITIONS: SOUTH BEND’S HOUSING IS INEXPENSIVE YET OUTOFREACH FOR MANY

Housing South Bend: Opportunities for transformative investment

Housing supply and demand

The previous subsection highlighted the gaps between

the housing people can afford and the housing that actu-

ally exists throughout South Bend. It shows large home-

owner appraisal gaps that may make home builders less

interested in investing in certain neighborhoods.

This next subsection disaggregates existing housing

supply by what is affordable to different income brack-

ets. By counting households within certain income

brackets and calculating 30% of that income bracket’s

lower threshold, it is possible to determine the mis-

match between the housing that’s available and the

population that can afford it.

The affordability picture in South Bend points toward

two groups facing an undersupply of housing: the low-

est earning South Bend residents and highest earning

South Bend residents (Figure 8).

Appraisal Gap in South Bend

FIGURE 8

Housing supply and demand by household income bracket

TABLE 1

Housing supply & demand, by income bracket (highlighted rows with undersupply)

Source: ACS 2019 5-year survey

Corresponding household

income bracket

Housing

costs

Supply (# of households

paying this for housing)

Demand (# of households

in this bracket)

Less than Less than

to to

to to

to to

to to

to to

or more or more

!

0 2,000 4,000 6,000 8,000 10,000 12,000

Less than $15,000

$15,000 - $24,999

$25,000 - $49,999

$50,000 - $74,999

$75,000 - $99,999

$100,000 - $149,999

$150,000 or more

Demand (no. of households in income bracket) Supply (no. of housing units aordable within that income bracket)

CHAPTER 1: EXISTING CONDITIONS: SOUTH BEND’S HOUSING IS INEXPENSIVE YET OUTOFREACH FOR MANY

Rice University Kinder Institute for Urban Research

Supply and demand was estimated using American

Community Survey data.

5

The households in the lowest income bracket, earn-

ing less than $15,000, represent about 18% of South

Bend’s households, but only about 11% of the city’s

housing stock is affordable to these earners. Because of

the undersupply of affordable housing for lower earn-

ers, households earning less than $15,000 must com-

pete for housing with higher-earning households or face

becoming unhoused.

There is also an undersupply of more expensive housing

in South Bend. Households earning more than $100,000

face a lack of housing supply and have the funds to out-

bid middle-income households for homes. Therefore,

even if there is a relative “match” for supply and demand

of housing for the middle income brackets, the under-

supply of options for higher-earning households puts

downward pressure on the rest of the housing market.

Positive signs, but some caution:

recession recovery, strong sales markets,

and decreasing vacancy

Despite home prices being relatively low compared to

other cities around the country, prices in South Bend

have been steadily increasing for more than a decade

following the Great Recession. The 2013 Vacant and

Abandoned Properties Task Force Report detailed the sig-

nificant challenges faced by the city in terms of housing

and foreclosure leading up to and during the housing

market collapse around 2008. Between 2001 and 2007,

the city experienced 6,777 foreclosures, according to

the report. In 2000, there were 27,054 owner-occupied

households in the city. While the city likely added more

homeowner households during 2001-2007, the ratio of

foreclosures to owner-occupied household count in 2000

suggests that a massive share of owner-occupied house-

holds in South Bend were foreclosed, somewhere in the

range of 15%-20%. This count of 6,777 foreclosures also

does not include the many foreclosures which happened

after 2008, when the global economy cratered.

5 ACS data contain counts of households by income bracket,

and counts of households by monthly housing expenses. To

determine affordability, researchers used 30% of the bottom

threshold of the income bracket (divided by 12, to determine

monthly income) in order to deduce the cost of housing each

household’s income bracket can afford. This helped determined

“demand”: that is, the number of households at each affordability

threshold. These counts were then aligned with the “supply”,

that is, the number of households paying different sums for their

monthly housing expenses.

In 2019, South Bend had approximately 22,600 own-

er-occupied households in the city, about 4,500 fewer

than in the year 2000.

Foreclosures have slowed down in the past 10 years.

From 2016-2021, only 455 foreclosure sales were listed

in MLS data, as opposed to close to 7,000 foreclosures

from 2001-2007.

There are more low-cost foreclosure sales in the city’s

western areas, while the higher-priced sales are in the

city’s outskirts. Certain neighborhoods in the city’s east

and south have high numbers of foreclosures, and fore-

closed homes with a high sale value. River Park, for ex-

ample, had at least 29 foreclosures in one of its census

tracts, and the homes generally sold for higher prices

than those to the west. This may speak to the need for

neighborhood stabilization, but with a different strat-

egy than the western neighborhoods, where property

values are more depressed.

Not many new homes have been built in the post-Great

Recession era. In the study period in this report (2016 to

May 2021), only 121 of the 5,998 home sales involved

homes built in 2010 or later.

Across the city, these newer homes tend to be more

expensive. Between 2016 and May 2021, homes built

in 2010 or later sold for roughly $227,000, on average,

while older homes sold for $102,000.

6

Housing prices have mostly recovered across the city

since the Great Recession. Using inflation-adjusted

home sales prices from 2007-2011 and comparing

them to home sales prices from 2016-2021, most areas

of the city have had their home prices return to their

earlier levels with some parts of the central city exceed-

ing earlier values (Figure 9).

Homes have increased in value the most in the

Northeast and the Near Northwest areas, with areas

northwest of downtown having the greatest price in-

creases. While “good news” at face value, these price in-

creases risk the area becoming unaffordable to current

and potential future residents.

6 Note that this is not a hedonic estimate that accounts for other

household characteristics that influence sales prices, such as size,

number of bathrooms, garages, etc.

CHAPTER 1: EXISTING CONDITIONS: SOUTH BEND’S HOUSING IS INEXPENSIVE YET OUTOFREACH FOR MANY

Housing South Bend: Opportunities for transformative investment

FIGURE 9

Change in average home sales price by block group, 2007-2011 vs. 2016-May 2021

CHAPTER 1: EXISTING CONDITIONS: SOUTH BEND’S HOUSING IS INEXPENSIVE YET OUTOFREACH FOR MANY

Rice University Kinder Institute for Urban Research

FIGURE 10

Average foreclosed home sales price by tract, 2016-May 2021

CHAPTER 1: EXISTING CONDITIONS: SOUTH BEND’S HOUSING IS INEXPENSIVE YET OUTOFREACH FOR MANY

Housing South Bend: Opportunities for transformative investment

FIGURE 11

Post-COVID-19 increase in average home sales price from by census tract

CHAPTER 1: EXISTING CONDITIONS: SOUTH BEND’S HOUSING IS INEXPENSIVE YET OUTOFREACH FOR MANY

Rice University Kinder Institute for Urban Research

FIGURE 12

Long-term vacancy (> 6 month) count by census tract, 2021

CHAPTER 1: EXISTING CONDITIONS: SOUTH BEND’S HOUSING IS INEXPENSIVE YET OUTOFREACH FOR MANY

Housing South Bend: Opportunities for transformative investment

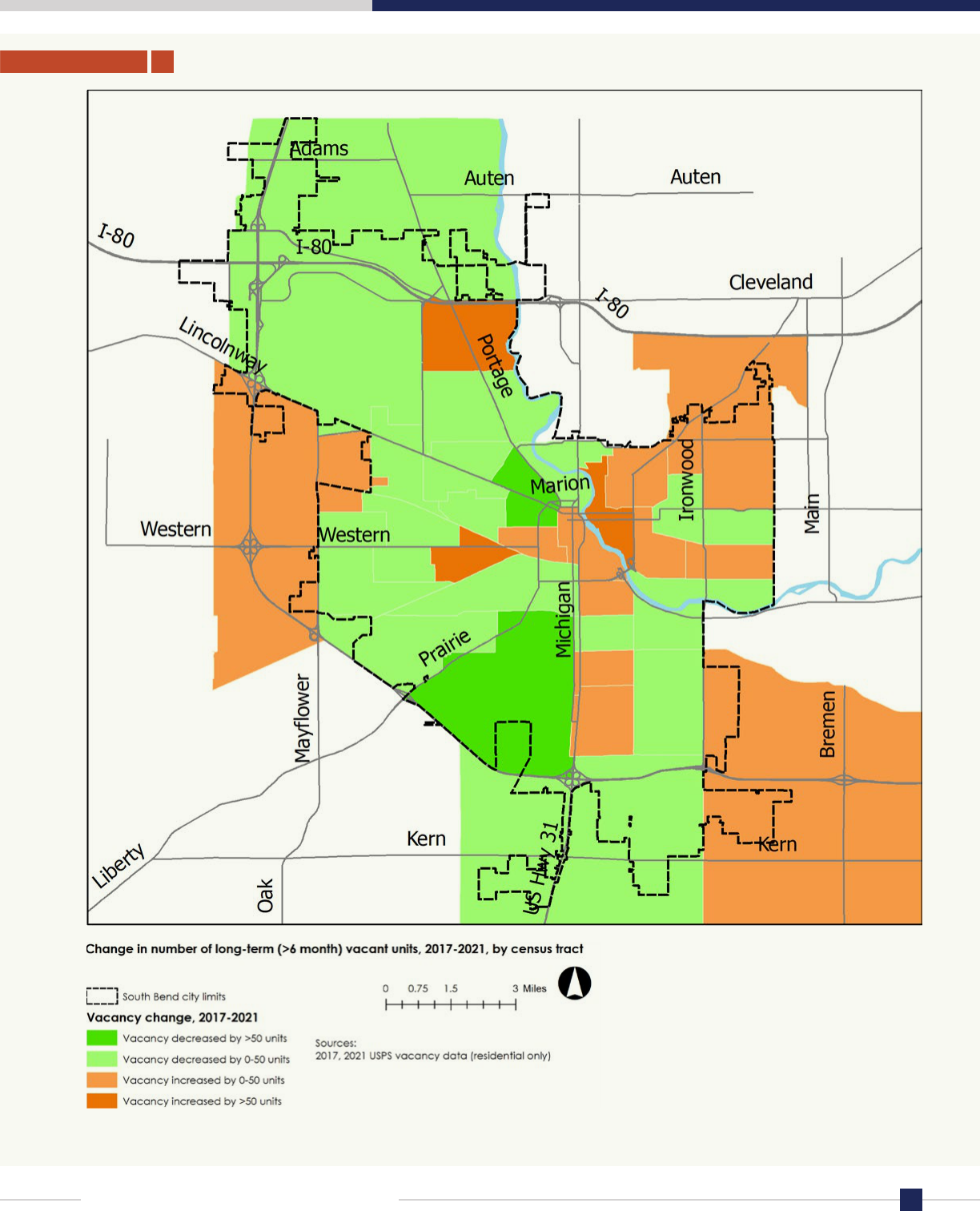

FIGURE 13

Change in long-term vacancy count by census tract, 2017-2021

CHAPTER 1: EXISTING CONDITIONS: SOUTH BEND’S HOUSING IS INEXPENSIVE YET OUTOFREACH FOR MANY

Rice University Kinder Institute for Urban Research

FIGURE 14

Tax sale eligible properties and median year built, 2021

CHAPTER 1: EXISTING CONDITIONS: SOUTH BEND’S HOUSING IS INEXPENSIVE YET OUTOFREACH FOR MANY

Housing South Bend: Opportunities for transformative investment

COVID-19 has increased home prices, though not every-

where. Citywide, home prices increased by about 4%

from the pre- to post-COVID-19 period. Specifically,

the average pre-COVID home sales price for the

2016-March 15, 2020 period was $103,073, while

homes sold after the COVID-19 outbreak (March 15,

2020) went for $107,191, on average (both figures are

inflation-adjusted to 2021 dollars).

The home price increase following the outbreak of

COVID-19 was not uniformly distributed across the city

(Figure 11). Price increases following COVID-19 have

been largest in the city’s western markets.

Sales volumes have generally been higher in the city’s

east and southeast. Southern neighborhoods like

Erskine Park and Tyckenham Hills have also seen a

particularly strong market, as has River Park. One

point to investigate, outside the scope of this report,

is examining who is buying these homes: investors or

owner-occupants?

Vacancy remains an issue within South Bend, mostly in

western neighborhoods, but there are likewise positive

signs. United States Postal Service (USPS) vacancy data

(Figure 12) can be used to analyze vacancy trends.

USPS notes when mail cannot be delivered to residen-

tial addresses because of vacancy, and these can be

aggregated to the census tract.

The largest number of vacancies can be found in west-

ern neighborhoods like Near Northwest, West Side, and

Rum Village, as well as near the university campus. The

census tracts containing the West Side and Southeast

are notable because they have high vacancy counts and

have not seen decreasing vacancies. Vacancy does not

appear to be increasing in most of the city’s older west-

ern neighborhoods (Figure 13).

According to USPS data, vacancy dropped dramatical-

ly in Near Northwest and Rum Village between 2017

and 2021. Decreases in vacancies can be attributed to

a building being either occupied or torn down, and the

high changes in vacancy count may indicate significant

real estate activity in those areas.

The overall picture of vacancy in South Bend is import-

ant to capture because of the scope and severity of the

issue. USPS data are a good source but are unable to

differentiate between housing that is abandoned and

housing that’s only lived in part of the year. Tax sale

data complement USPS data by helping distinguish

between different types of vacant properties, between

“newer” vacancies and old vacant properties where

taxes have not been paid because of abandonment,

speculation, or because a homeowner is not able to pay.

Aligning tax sale data with neighborhood age data show

the intersecting challenges of abandoned properties

and home age.

Tax sale eligible properties are concentrated within

South Bend’s challenged neighborhoods in the west

(see Figure 14). These areas also contained aged build-

ing stock which may be in need of significant repair or

replacement, something which ARP funds can address.

Prior plans and studies: Unmet housing

demand exists in central South Bend

Market studies

Prior analysis in this report illustrated the affordability

gap, the appraisal gap, and other trends in South Bend’s

housing market.

Another series of studies, commissioned by the city in

2018 and 2021, have looked to understand the poten-

tial future demand in certain South Bend neighbor-

hoods. All of these analyses and studies can help South

Bend decision-makers direct ARP funds, and are used

to inform this study’s final chapter.

These prior plans and studies analyzed the residential

market potential of diverse South Bend neighborhoods

(see Table 2). Each plan forecasted annual demand for

both existing and new housing, dividing housing type

and demand by income strata, tenure, and building type.

Taken together, the studies forecasted a demand for

roughly 1,400 to 1,715 new units (both rental and

owner-occupied) in the centrally located and stron-

ger real-estate markets in Downtown, East Bank, and

Northeast. A slight majority of this projected demand

was expected to be rentals. Even the weaker real estate

markets in the west and south were still projected to de-

mand between 183 and 242 new units, with the majori-

ty of new build demand being for rentals.

In each of the studies, there is notable demand for low-

er-income housing units.

Downtown and Northeast have the largest potential mar-

ket, with over 3,000 households in their potential market

compared to less than 1,000 in most other geographies.

While they have higher property values than the western

neighborhoods studied, Downtown and Northeast still

have high demand for lower-income housing.

CHAPTER 1: EXISTING CONDITIONS: SOUTH BEND’S HOUSING IS INEXPENSIVE YET OUTOFREACH FOR MANY

Rice University Kinder Institute for Urban Research

There is a strong demand for affordable housing across

all areas studied, not only in less wealthy neighbor-

hoods. Across all geographies, lower-income house-

holds are projected to be about half of the total poten-

tial demand for housing.

All geographies have a higher absorption rate for rental

properties, which signifies an undersupply of high-qual-

ity affordable rental properties across South Bend. This

suggests that new rental property managers will likely

have an easier time finding residents than owner-occu-

pied properties.

However, Rum Village and East Bank have relatively

equal demand for new rental and owner-occupied

properties.

Neighborhood plans

Existing plans and other studies guide decision-makers

toward previously identified neighborhood concerns,

or potential investments, that can be targeted with ARP

funds (Table 3).

All plans emphasized vacant home remediation, reha-

bilitation, subsidizing affordable home development,

and other policies that advance new home construction

and existing home repair, and identified specific com-

munity partners who can take a lead role in real-estate

development. Other central issues included infrastruc-

ture improvements, road redesign, and open-space and

parks planning. Certain plans also identified useful

sites for development, such as “neighborhood nodes”

within the Lincoln Park plan.

The Vacant and Abandoned Properties Task Force Report

deserves special mention, as it highlights South Bend’s

citywide housing challenges. This 2013 study investi-

gated the extent of vacant and abandoned homes within

South Bend. The report included a map that catego-

rized the city according to four levels of redevelopment

potential. This map may be a useful guide for future

investments and identifies parts of the city in need of

targeted housing investments. Among the many policy

recommendations and investments were the formation

of a land bank; more assertive code enforcement; and

targeted investments to help repair vacant homes that

are repairable.

In addition to the plans and studies outlined above,

South Bend has been producing neighborhood plans

for Rum Village, New West Side, Kennedy Park, and

Northeast during the process of writing this study.

TABLE 2

Market analyses

Neighborhood

studied Year

New units

absorbable, years

- Rental

New unit

absorbable, years

- Owner

Number of

households in

potential market

Number of

households in

potential market

earning <% AMI

Near Northwest/

Near West Side

- - renter,

owner

Monroe Park/

Southeast

- - renter,

owner

Rum Village/

eastern West Side

- - renter,

owner

Downtown - - renter,

owner

East Bank - - renter,

owner

Northeast - - renter,

owner

West Side

corridors

Not available

CHAPTER 1: EXISTING CONDITIONS: SOUTH BEND’S HOUSING IS INEXPENSIVE YET OUTOFREACH FOR MANY

Housing South Bend: Opportunities for transformative investment

FIGURE 15

Neighborhood types from Vacant and Abandoned Properties Task Force Report, 2013

CHAPTER 1: EXISTING CONDITIONS: SOUTH BEND’S HOUSING IS INEXPENSIVE YET OUTOFREACH FOR MANY

Rice University Kinder Institute for Urban Research

TABLE 3

Recent relevant neighborhood plans and studies

Plan/study name Year Description Key components

Neighborhood, corridor, and areal plans

Lincoln Park

Neighborhood

Revitalization Plan

Neighborhood

revitalization plan

for northwest

of downtown

neighborhood

Revitalization plan focuses on vacant home

remediation, home improvement, and new home

construction.

Howard Park

Neighborhood Plan

Neighborhood plan

for east of river

neighborhood

Plan includes recommendations for development

of former Transpo site and other infill sites;

recommends improving pedestrian and cycle

infrastructure around park.

Commercial Corridor

West Side Main Streets

Plan for improving

west side corridors

Plan focuses on potential improvements to

Western Avenue Corridor and Lincoln Way West

Corridor; also concerned with neighborhood

revitalization around renovated streetscapes.

Southeast

Neighborhood Master

Plan

Neighborhood plan

for southeastern

neighborhood

Plan focuses on community investment and

stabilization.

Key recommendations: improve and develop

vacant lots; corridor and park improvements.

Near Northwest

Neighborhood Plan

Neighborhood plan

for neighborhood

northwest of

downtown

Plan recommendations focus on infrastructure

improvements, mediating abandoned properties,

helping close the appraisal gap, and promoting

area as a mixed-use urban area.

Miami Hills

Neighborhood Plan

Neighborhood

plan for south side

neighborhood

Neighborhood plan for south side neighborhood,

addresses infrastructure, transportation and

multi-modal connections, recreation, and creating

a variety of housing types.

Other relevant studies

Vacant and

Abandoned Properties

Task Force Report

Report on status and

remediation of local

abandoned properties

Study develops process for categorizing and

handling vacant homes,

Key recommendations: forming a land bank,

aggressive code enforcement.

Plan includes map of abandoned properties, and a

map of neighborhood market classification.

CDBG RFP Yearly CDBG RFP CDBG plan addresses housing investment; shows

recommended areas for housing investment:

Southeast of Ivy Tech

Two sections of Near Northwest

CHAPTER 1: EXISTING CONDITIONS: SOUTH BEND’S HOUSING IS INEXPENSIVE YET OUTOFREACH FOR MANY

Housing South Bend: Opportunities for transformative investment

Summary of scenario process

The main goals of this phase were to:

1. Develop a tool that South Bend could use to help

make decisions about how to allocate ARP funds.

! A pro forma model was built to estimate how

much housing the ARP allocation could help

subsidize, using pre-approved home construction

plans and construction cost estimates from the

City of South Bend.

2. Test (and hone) that tool by drafting three scenarios

for how the ARP funds could be allocated.

! Each scenario’s focus is specific and unique:

— Affordable housing in South Bend’s

most cash-strapped communities

— Neighborhoods on the brink get

affordable housing

— Rehab, renew, and build affordable homes

3. Outline the lessons from scenario building

and vetting phase in order to inform the final

recommended options.

! Building homes affordable to low-income

residents (80% median income) and not

extremely low-income residents (<30% median

income), allows the city’s ARP allocation to build

more homes, but it risks not addressing the city’s

neediest residents, who have the largest gap

between supply and demand.

! Outside equity, a mix of market-rate units, and

larger down payments would allow the ARP

funds to go further when building affordable

rental housing. Without a large down payment

or outside equity, the operating costs of

maintaining the units would exceed the revenue

they generate.

! Rehabilitation could be more cost-effective than

building new homes, but significant money is

needed to fix South Bend’s most damaged building

stock. The cost of a down-to-the-studs renovation

is effectively equal to building a new home.

Developing and presenting these scenarios helped

hone the pro forma model, and provided crucial

information to inform recommended options

(discussed in Chapter 3).

First, what is meant by “scenario”

The term “scenario” means a “potential way the money

could be spent.”

Scenario planning is a common strategy in private busi-

ness, urban planning, and other sectors. Through devel-

oping scenarios around certain policy choices—such as

how a lump sum of money could be spent on affordable

housing—policymakers and the public can discuss the

future effects of these present decisions on their com-

munity and craft resilient, robust strategies.

The scenarios are hypothetical ways that the city’s $5.5

million ARP allocation could be spent.

This report’s ARP funding scenarios are not explic-

it plans or policies. The scenarios are exercises that

identify more specific ways the money could be spent

and highlight tradeoffs between decisions. Again, the

ARP funding scenarios described in this chapter are not

explicit plans or policies.

Chapter 2:

Building ARP

spending scenarios

CHAPTER 2: BUILDING ARP SPENDING SCENARIOS

Rice University Kinder Institute for Urban Research

Lessons from existing conditions

Existing research identified baseline conditions for

developing different scenarios, along with showing key

problems the ARP funds could address. The section

that follows briefly describes existing conditions, and

how they relate to ARP funding choices.

Demand exists for central-city housing. Market studies

conducted for the city of South Bend show that thou-

sands of new rental and owner-occupied units can be

absorbed across multiple central South Bend neighbor-

hoods on both sides of the river. Recent construction

and high post-COVID-19 price spikes also evidence

high demand. In recent history, the city has reformed

its zoning ordinance and written other policies, such as

pre-approved plans for smaller lots, to help streamline

central-city development.

The city’s neediest residents need quality housing.

There are four census tracts within South Bend—mostly

covering downtown and the areas to its west—where

the median household income is less than $20,000.

(In 2021, the federal definition of living in poverty

for a family of four was an income of $26,500 or less).

Residents are housing cost-burdened. While neither

researchers nor the city possess detailed and reliable

parcel-by-parcel building quality surveys, these same

areas also have extensive vacancy, suggesting blight and

lower-quality structures in which residents live. These

two phenomena jointly suggest the need for quality,

affordable housing. Citywide, there is evidence that

the poorest residents are those which face the largest

under-supply of housing.

There is demand for new owner-occupied housing

stock. The strong post-COVID-19 real-estate market

is uneven. Relatively few new homes have been built

since 2016. Home vacancy, despite some positive signs,

remains common. While the city has reformed policies

to encourage development, the local home construction

sector has been slow to respond. Newer homes can give

appraisers “comps” they can use during the mortgage

appraisal process, yet new home construction may risk

accelerating unaffordability.

Certain neighborhoods may become unaffordable.

There are many neighborhoods on the cusp of chang-

es, which the ARP subsidy can address. Places like

the Near Northwest, Northeast, and River Park face

challenges in 2021. These include areas with some

of the most active post-COVID-19 markets. Because

property values have increased, these neighborhoods

may become unaffordable for older residents looking to

relocate to different homes in the neighborhood. They

also may lack vacant land within portions of the neigh-

borhood for new affordable homes, or they may have

older properties in need of rehabilitation.

Estimating ARP-subsidized housing costs

and aordability: the key assumptions

As part of the scenario building, estimates of the impact

of ARP investments were generated using a spreadsheet

model similar to a real-estate pro forma. Like any cost/

revenue real-estate estimation model, certain assump-

tions about interest rates, construction costs, future

revenues and other variables were made.

Potential ways money can be spent on housing:

This report chose to focus on housing construction and

rehabilitation because the ARP Final Rule, as issued by

the U.S. Treasury, emphasizes “[p]romoting long-term

housing security” [emphasis added] for communities,

and brick-and-mortar affordable housing investments

are permanent in a way direct cash subsidies are not.

Additionally, other ARP funds in South Bend went

toward emergency rental assistance. While these emer-

gency funds were a crucial and sometimes a literally

life-saving measure, the terms of the final rule limits

how these funds can be applied.

Therefore, in these scenarios, there are three ways

money can be spent:

(1) Constructing owner-occupied housing,

(2) Constructing renter-occupied housing, or

(3) Rehabilitating existing homes, either owner- or

renter-occupied.

In these scenarios and within the pro forma model, the

ARP allocation subsidizes private development and

repairs. The city is not a development firm. In the case of

owner-occupied housing, the ARP money goes toward

covering the gap between what South Bend residents can

afford, and what it costs to build housing. For renter-oc-

cupied housing, ARP money goes toward the down pay-

ment on construction-to-permanent loans that finance

affordable housing. Rehabilitation money hypothetically

goes directly to property owners or their contractors.

CHAPTER 2: BUILDING ARP SPENDING SCENARIOS

Housing South Bend: Opportunities for transformative investment

Housing construction cost estimates come from

pre-approved plans. To determine how far the ARP

funding could go, reliable housing construction costs

are needed for different housing types. South Bend

staff provided pre-approved house construction plans

from the South Bend Neighborhood Infill Study. For

the infill study, consultants created pre-approved

construction plans for infill housing that fits existing

city building and zoning codes. The house plans are

also appropriate to the smaller lot sizes often found in

South Bend’s central neighborhoods. These plan types

are for single-family homes of different sizes, duplexes,

and sixplexes (see Table 4). These construction plans

were created prior to the recent inflation increases, so

the pro forma model allows for the user to change cost

estimates based on inflation and other factors.

Affordability varies by neighborhood and family size.

While construction costs are relatively similar across

the city, median household income varied by neigh-

borhood. The scenarios attempted to account for these

differences in income at the tract level when determin-

ing investments.

Affordability guidance largely comes from the U.S.

Department of Housing and Urban Development

(HUD). HUD issues income definitions for guiding how

cities can spend grants from the HOME Investment

Partnerships Program. Given how ARP funds were

federally disbursed, it made sense to consider federally

issued affordability guidelines within the pro forma. See

Table 5 for the affordability limits used in this report.

Extensive detail about this program, and certain chang-

es, can be found in the Appendix.

TABLE 4

TABLE 5

Pre-approved plan details. Source: City of South Bend, Neighborhood Infill Study

FY2022 HUD Income Limits

Type Standard

Standard

Suite

Narrow

House

Narrow Suite

Carriage

House

Duplex Sixplex

SF/unit

BR/unit

Estimated

construction cost

Min. lot width (ft.)

Estimated

construction cost

Estimated

construction cost,

% inflation

Aordable housing costs (% of monthly income per FY HOME income limits)

-Person

Household -Person Household -Person Household

-Person

Household -Person Household

% AMI

% AMI

% AMI

% AMI

CHAPTER 2: BUILDING ARP SPENDING SCENARIOS

Rice University Kinder Institute for Urban Research

For the purposes of these scenarios, the affordability

definitions for each unit come from the bedroom count.

Two-bedroom duplex and sixplex units’ affordability

definitions come from the two-person family affordabil-

ity level; three-bedroom standard and narrow homes

from a three-person family; and four-bedroom narrow

suite and standard suite definitions for a four-person

family. For example, consulting Table 5, a two-bedroom

duplex that is affordable for an extremely low-income

(30% MHI) family would rent for $469. A four-bed-

room single suite home affordable for very low-income

families (50% MHI for the purposes of this report)

would cost $975 per month. Family size and number of

bedrooms do not always align, but this assumption is

deemed defensible.

The tool was vetted by the South Bend project team in

April 2022. Critiques included accounting for vacant

land, improving operating expense estimation, and

other topics.

Given how the scenarios were created under an earlier

draft of the pro forma model, details are omitted with-

in the main narrative and moved to the appendix. The

main reason for this phase was to investigate different

potential broad strategies, and the potential tradeoffs

of different policy choices, rather than estimating the

most efficient or best investment.

There are certain limitations of the pro forma model.

! The model omits certain construction assumptions,

such as asset depreciation and construction staging.

! The model has less detailed assumptions for

construction costs and cannot estimate shortages

or severe price spikes in certain materials. Even

commonly used pro forma models cannot account

for these spikes.

These limitations reflect the fact that the tool is for

investing across multiple projects, and not providing

detailed financial estimates for individual projects.

Given the potential for cost overruns, due to things like

inflation or material shortages, all scenarios (and final

recommended options in the next chapter) do not advo-

cate spending the full $6 million.

How far can the ARP funding go?

The pro forma tool was used to estimate how much

housing could be built with $5.5 million.

In these estimates, which use the final pro forma model,

land is assumed to be free, so construction would need

to occur on city-owned or vacant property.

Assume ARP funds only build owner-occupied

four-bedroom single-family pre-approved “Standard”

homes at $282,000 each.

For the purposes of this study, the ARP funding subsidy

covers the gap between what the home costs the person

(Table 6, column 1) and the actual construction costs

($282,000 in this case).

Table 6, which shows how far the ARP funding could

go if only building four-bedroom standard homes and

the cost estimates,

7

makes a few lessons apparent. First,

even a $200,000 home is “affordable” per the HOME

affordability thresholds for a family of four. Second,

extremely affordable housing is more expensive to build

and requires more subsidy, leading to fewer overall

units being built.

All told, the allocation can subsidize 23-66 affordable

standalone “standard” homes.

7 Assumptions for these estimates: mortgage interest rate 4.5%

with 30-year amortization period; property tax rate 1%; property

insurance rate 1%; Mortgage insurance rate 0.85%; Down

payment 3.5%

TABLE 6

How many $282,000 homes can

the ARP funding subsidize?

Home sales price

Estimated

monthly occupant

cost

Number of homes

buildable with

ARP allocation

CHAPTER 2: BUILDING ARP SPENDING SCENARIOS

Housing South Bend: Opportunities for transformative investment

TABLE 7

TABLE 8

Assume ARP funds subsidize one sixplex with six

two-bedroom units. The building costs $754,000 to

build on free city-owned land, with no investor equi-

ty and 50% money down, with the rest of the costs

financed by a construction-to-permanent loan. We

assume a 10% vacancy rate.

Sixplex “break even” on

costs v. affordable rent

Aordability

threshold Rent

Does the building

break even on

costs?

Extremely

aordable

(% AMI)

No

( short

per month)

Very aordable

(% AMI)

No

( short

per month)

Aordable

(% AMI)

Yes

( surplus

per month)

All rental units have regular costs. In addition to main-

tenance, upgrades, property tax, “wear and tear,” and

paying property management staff, property managers

also need to pay back the loans needed to pay for con-

struction. In “market-rate” units, rent hypothetically

covers all of these costs. For affordable units, addition-

al funds are needed. Within this study, ARP funds go

toward larger down payments in order to minimize loan

servicing costs, which helps keep rents lower.

In this example, operating expenses, estimated to be

$2,285 per month for the entire building, account for

maintenance costs, upgrades, insurance and a “rainy

day” fund.

8 Researchers assume with a 20-year construction-to-permanent

loan with 6.5% yearly interest and 10% vacancy rate.

This cost breakdown (Table 7) for this unit shows the

need for outside equity, or a number of market-rate

units, in order to help the development “break even”

and take in enough revenue to keep up with repairs.

Note that even 80% AMI “affordable” units are well

above median rents for South Bend and barely break

even. Without these subsidies in addition to ARP funds,

too much money is spent on loan servicing and not

repairs, and the project cannot cover regular costs if the

rental units serve the neediest residents.

Assume ARP funds go toward one sixplex with six

two-bedroom units. The above assumptions are the

same, except investor equity covers 33%, a down pay-

ment covers another third, and a construction-to-per-

manent loan covers the last third.

Sixplex “break even” on costs

with investor equity and

affordable rent

9

Mix of units

Does the building

break even on costs?

rent at

(aordable)

rent at

(extremely aordable)

No

( short per month)

rent at

(aordable)

rent at

(very aordable)

Yes

(Barely, positive

per month)

rent at

(market rate)

rent at

(very aordable)

Yes

( positive per month)

A large down payment is needed for affordable rental

housing to break even (see Table 8). Even with a down

payment that covers one-third of the cost of construc-

tion, and private equity covering another third, the

building is not netting a large positive cash flow. A very

large down payment is necessary.

9 Cost assumptions are assumed to be same as Table 8.

10 Ibid.

CHAPTER 2: BUILDING ARP SPENDING SCENARIOS

Rice University Kinder Institute for Urban Research

Assume ARP funds only go toward extensive

rehabilitation.

Low-cost rehabilitation can spread benefits to many

households but are smaller-scale improvements com-

pared to new-home construction.

Higher-cost rehabilitation is still roughly one-half the cost

of building a new home, and it may not entail all of the

work necessary to modernize homes with new fixtures.

Note that the cost estimates in Table 9 assume no soft

costs for running a rehab program, which will be neces-

sary as city staff time will be needed to run the program.

Three scenarios for spending ARP funds:

There are infinite calculations researchers could make

in order to show “how far” the ARP money could go. To

help hone the process, project staff devised comprehen-

sive yet hypothetical scenarios for how the money could

be sent. Feedback from these scenarios form the basis

of Chapter 3.

11

Policymakers and the general public can use the scenar-

ios to better understand the types of choices they have

for the ARP allocation and the potential outcomes of

those choices.

11 A second key purpose of the scenario process was honing the pro

forma tool. Project staff presented the tool, and scenarios, in April

2022, and the pro forma tool was developed further following

feedback at this meeting. Since the scenarios were built with an

older “Version 1.0” of the tool, their full details (regarding costs

and revenues) are not included in the body text. Please consult the

appendix for full information.

TABLE 9

Rehabilitation budget

Rehab budget per home

How many homes can receive funds?

(ARP allocation divided by budget)

Items that can be repaired within that budget

(assuming only one item is chosen, not the entire list)

! Bathroom fixture updates

! Kitchen fixture updates

! Minimal foundation issues

! Extensive landscaping improvements

! Siding and paint repair

! Gutter replacement

! Moderate HVAC updates (e.g., replacing a heater)

! Major roof repairs

! Significant HVAC updates (e.g., installing ductwork)

! Extensive window replacements on historic homes

! Extensive siding replacement

! Extensive foundation repairs (e.g., lift and fill)

! Complete plumbing replacement

! Fixing water damage

! Down-to-the-studs renovation of a portion of a home

CHAPTER 2: BUILDING ARP SPENDING SCENARIOS

Housing South Bend: Opportunities for transformative investment

Scenario 1. Aordable housing in South Bend’s most

cash-strapped communities

The goal of this scenario is to house residents of South

Bend’s poorest census tracts.

What and where

In the first scenario, all of the ARP builds and renovates

housing in census tracts 20, 21, and 23, which includes

parts of the Near West Side, Kennedy Park, and La Salle

Park. These are South Bend’s communities with the

lowest median incomes, all below the poverty line for a

family of four.

There is about a 50-50 split between very/extremely

affordable rental housing (17 units) and market-rate

rental housing (19 units). As mentioned above, this

sort of “split” helps the project’s financial viability, and

increases the likelihood of wealthier residents (who can

afford market-rate units) moving into these neighbor-

hoods. The subsidy sponsors a small amount of own-

er-occupied housing (10 units), which must be heavily

subsidized to be affordable. The remaining funds are

set aside for rehabilitation.

What’s the story? Justifications and tradeos

As cited in the existing conditions, these areas of South

Bend have a high amount of vacancy and older homes.

Two of the three tracts have a high renter affordability

gap, signaling the need for affordable housing.

New high-quality homes can help improve sagging

appraisal values.

Targeting these neighborhoods for funds has important

equity considerations, as residents have lower incomes,

and have also historically borne the brunt of structural

inequities.

One potential concern: Wealthier residents may raise

local anxieties about gentrification and displacement.

Measuring how much these new homes may “cause”

gentrification, or measuring if gentrification is a poten-

tial outcome, is beyond the scope of this report, but the

presence of even a few wealthier residents in high qual-

ity homes in these neighborhoods may raise concerns.

This problem could be addressed by either building only

extremely affordable housing (which means less hous-

ing could be built).

Scenario 2. Neighborhoods on the brink get

aordable housing

The goal of this scenario is to provide permanent, af-

fordable housing in neighborhoods with strong, grow-

ing markets, where high demand and post-COVID-19

price increases signal coming affordability challenges.

What and where

The focus of this scenario are census tracts 7, 10, and

17, which includes the highest demand areas in the

market studies. Such communities are not wealthy:

these tracts vary from being very low income (tract 17,

which is downtown and has a MHI less than $20,000)

to middle-income (with MHIs in the $40,000-$55,000

range). Future real-estate development may likely be

too expensive for existing residents.

To help address this issue, this scenario entails build-

ing an even mix of owner- and renter-occupied homes.

Having more affordable owner-occupied homes (21)

than the previous scenario may help prevent displace-

ment, as does building relatively affordable rental hous-

ing (28 units). These rental units are generally more

expensive than those in the first scenario.

What’s the story? Justifications and tradeos

Since these areas are higher-demand, and places where

the city cannot as easily grant land to a developer, this