1

Home Fires Burning: The London Fog of 1952 and the

Movement to Clean Air

Emily Eckert

Barnard College, Department of History

Thesis Advisor: Professor Deborah Valenze

17 April 2019!

2

Table of Contents

Introduction 3

Chapter I: Seeing through London’s Problem with Fog 6

Chapter II: Britain’s Shift to Coal and Early Air Pollution Monitoring 12

Chapter III: From London Particular to Deadly Phenomenon 24

Conclusion 43

Bibliography 45

3

Introduction

London was both the phenomenon and the place that made fog famous. Whether used

as a veil to conceal crime in the stories of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, as a

symbol of urban gloom in the novels of Charles Dickens, or captured by artist Claude Monet

in his paintings of the Thames, London fog was a recognizable element of British culture.

While fog functioned as a device for scene setting in literature and art, it became legendary

throughout much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as an inescapable part of city life.

London’s well-known fogs were gritty and yellowish, caused by the burning of sulfurous coal

and the subsequent production of smoke that coupled with and stayed trapped in the

atmospheric wetness of naturally occurring fogs. One particularly terrible fog descended on

London for four days in December 1952. It settled over the city and prevented chimney

smoke from rising and escaping while also keeping new air from coming in. The smoke from

the millions of domestic coal fires remained trapped as the city continued to burn more fuel

during those cold December days. Ultimately these conditions led to the deaths of thousands

of people (possibly as many as 12,000) namely through the fatal exacerbation of respiratory

conditions like asthma, bronchitis, and other lung conditions.

The London fog of 1952 was a catastrophic event, though it remains understated

in the chronicling of British environmental history. One has likely never heard of it unless

they recently watched Season 1 of Netflix’s The Crown, which traces the life of Queen

Elizabeth II starting from the 1940s. The episode titled “Act of God” covers the dense,

crippling fog in a comprehensive manner, even touching on the government’s reluctance to

respond to the crisis in its immediate aftermath. In order to do justice to the severity of the

fog, The Crown’s director Stephen Daldry chose not to rely on computer-generated special

4

effects, but instead he had the production company fill a great huge warehouse with fog.

1

Similarly, in a recent episode of the classic American television game show Jeopardy, an

answer to a clue relating to London’s deadly fog appeared in a category titled “Apocalypse

Then.” Considering the 1952 fog in this light, as an apocalyptic killer rather than something

to be merely tolerated and endured, marks a shift in environmental thinking and societal

perception. Though such a view is very much a part of our current narrative, Londoners in

1952 were slow to view their fog in such terms.

British historian Christine Corton meticulously captures the subject of London fog in

London Fog: The Biography through a wealth of representations of fog in popular culture,

literature, cartoons, and art history. Much of her work is grounded in the metaphorical and

symbolic use of fog in literature. As an overall study of London’s atmosphere, this source is

very useful, yet her overall approach gives too much attention to fog fiction. Peter

Brimblecombe’s The Big Smoke: A History of Air Pollution in London since Medieval Times

offers insight into smoke abatement movements and early attempts at legislation to curb air

pollution. His engaging account of the social and economic development of air pollution

controls provides helpful background for the legislative history of London’s clean air. The

story of air pollution in London leading up to the 1952 fog, the “Big Smoke,” or the “Great

London Smog” as it is often called today, is not just to be a biography of fog, however. It is a

story of how London’s fogs became inseparable from London’s chimneys. The environmental

danger of coal smoke from domestic chimneys went largely unrecognized, and popular

individual complicity in the burning of domestic coal fires posed a strong obstacle for

legislative regulation.

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

1

Kate Samuelson, “Everything to Know about the Great Smog of 1952, as Seen on The Crown,” Time

Magazine, November 4, 2016.

5

This thesis aims to build off the existing scholarship by using Parliamentary debates in

the decades before the 1952 fog and in the years after the disaster as the essential foundation

in tracking the developments of environmental perspectives in London. In seeking to trace

cultural assumptions of London’s fog, this thesis relies particularly on newspaper articles from

sources such as The Daily Telegraph and The Manchester Guardian to investigate the way the

1952 fog was reported and the change in public opinion that ensued. This thesis seeks to

answer why Londoners tolerated sulfurous fogs for centuries, why they did not immediately

view the 1952 fog as a crisis, and why the government’s response to the disaster remained

lackluster until a year after the incident.

Ultimately, Parliament passed the Clean Air Act of 1956 in response to the disaster,

and it took the 1952 fog for Britain to not only make a change toward cleaner air but to change

the perception of fog in the public mindset. London’s general public did not perceive the

1952 fog as an immediate crisis—for most, it was part of the modus operandi of London life.

Only when hospital records were made official and national statistics realized did a

psychological shift take place. As the severity of the incident was grasped in the aftermath, a

shift in collective consciousness became both conceptual and linguistic: London’s historic fog

became smog. The 1952 disaster was thus a critical juncture in which London’s fog

underwent a transformation in British cultural imagination.

6

Chapter I: Seeing through London’s Problem with Fog

One of the earliest and most extensive denunciations of London’s smoky atmosphere

was by diarist John Evelyn, who presented his Fumifugium: or the Inconvenience of the Aer

and Smoake of London Dissipated to Charles II in 1661. Evelyn suggested that the burning of

sea coal shortened the lives of people living in London, and he regarded it as a “sullen” fuel

that wreaked havoc on architecture, vegetation, and human health.

2

Evelyn brought attention

to the general decline in health that came from a smoke-filled atmosphere, and he also sought

to challenge and disrupt the ingrained societal idea that there could be no fire without smoke.

3

He reasoned that the objectionable smoke was “not from the culinary fires, which for being

weak, and lesse often fed below, is with such ease dispelled and scattered above.”

4

His

treatise firmly blamed industry for London’s smoke problem however, and saw a feasible

solution in relocation, arguing to move smoke-producing works outside of the city.

5

His

document laid the groundwork for a debate on smoke that would continue for centuries, and

though his argument placed the blame on the industrial side, it was critical in establishing the

smoke problem as a London problem. Throughout the nineteenth century London fogs

increased in both frequency and duration, and by the 1880s, there were on average sixty fogs a

year.

6

Journalistic benchmarking confirms that fogs consistently disrupted street/river traffic

as well as the casual labor market, with midday close-downs becoming more commonplace.

7

The fogs were so prevalent that journals like the Builder in 1859 complained that Londoners

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

2

Peter Brimblecombe, The Big Smoke: A History of Air Pollution in London since Medieval

Times (Oxford: Routledge Revivals, 2011), 49.

3

Brimblecombe, The Big Smoke, 49.

4

Christine Corton, London Fog: The Biography (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015), 3.

5

Brimblecombe, The Big Smoke, 49.

6

PD Smith, “London Fog by Christine Corton – the history of the pea-souper,” The Guardian, Friday

Nov. 27, 2015

7

Bill Luckin, “‘The Heart and Home of Horror’: The Great London Fogs of the late Nineteenth

Century, Social History, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Jan. 2003): 34.

7

endured fog conditions akin to semi-darkness.

8

Fogs were therefore an established component

of the metropolis, and Londoners were familiar with their severity.

London fogs had their own distinctive character which gave them a certain

memorability, as sulfurous soot particles in the air mixed with naturally occurring water vapor

to create an atmosphere that was thick, persistent, and often described as greenish-yellow or

even black in color.

9

This was so much the case that the public denoted these fogs as

‘London particulars’ as early as the 1830s. Cartoon artist Michael Egerton was one of the first

to use the term London particular in one of his color lithographs in 1827. Egerton depicts a

man of fashionable, Regency-style dress, making his way through a foggy city, seemingly

unable to view the oncoming horse and carriage in his path as he holds a yellow handkerchief

to his mouth as a means of protection against the pollutants in the air (see Fig. 1).

10

It is an

image that confirms the commonplace nature of a fog serious enough to block a man’s view of

his periphery and require the use of a handkerchief while navigating London’s streets. Though

the notion of a London particular was quickly becoming used in a colloquial manner, it was

indeed something particular to London, as fogs of this coloring and density were not found

elsewhere, even in the most polluted cities of the industrial north.

11

The idea of the London

particular was so compelling that even leading Victorian art critic and historian John Ruskin

commented on it in one of his lectures, referring to a London particular as an “extremely

cognizable variety of that sort of vapour” which he saw as the “especial blessing of

metropolitan society.”

12

As a linguistic term a ‘London particular’ was so prevalent that even

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

8

Luckin, “‘The Heart and Home of Horror’: The Great London Fogs,” 34.

9

Corton, London Fog: The Biography, 14.

10

Corton, London Fog: The Biography, 24.

11

Corton, London Fog: The Biography, 24.

12

Corton, London Fog: The Biography, 25.

8

The New York Times in 1855, describing an American fog, wrote that except for its density,

the fog had “none of the characteristics of our ‘old London particular.’”

13

A Thoroughbred November & London Particular

by Michael Egerton, engraved by George Hunt,

published by Thomas Mclean, London, 1872

(color lithograph)

The term ‘London particular’ appears to have

become an accepted term for fog by the date of

this engraving.

The Stapleton Collection, Bridgeman Images.

Courtesy of Christine Cotton, London Fog: The

Biography, p. 24

London particulars gained such a reputation that nineteenth century visitors anticipated

the phenomenon. In 1888, James Russell Lowell, an American poet who also served as the

U.S. Minister to England, wrote to an acquaintance while visiting London:

“We are in the beginning of our foggy season, and to-day

are having a yellow fog, and that always enlivens me, it

has such a knack of transfiguring things. It flatters one’s

self-esteem, too, in a recondite way, promoting it is very

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

13

Corton, London Fog: The Biography, 25.

9

picturesque also. Even the cabs are rimmed with a halo,

and people across the way have all that possibility of

suggestion which piques the fancy so in the figures of

fading frescoes. Even the gray, even the black fogs make a

new and unexplored world not unpleasing to one who is

getting palled with familiar landscapes.”

14

Lowell’s writing conveys an eagerness to witness what had become such an expected aspect

of staying in London. His take on the foggy season denotes the pervasiveness of London fogs,

and his characterization of fogs as that which enlivens and transforms the environment points

to a foreigner’s excitement toward the unaccustomed. To Lowell, part of his adventure of

being in London was witnessing the fog. Indeed a ‘London particular’ was something unique

and almost enviable, especially in the eyes of an American. London’s cliché fogginess was

secure for decades to come.

Though London particulars grew to have a certain affinity, there were also voices

which sought to raise awareness for their danger. One of the most prominent and intensely

prophetic voices was that of Robert Barr (1850-1912). Barr was born in Scotland and moved

to Canada when he was a child. He relocated to London as an adult and was eager to capture

and write about London fog, a phenomenon which he had never previously experienced. He

began prolifically publishing short stories in the 1890s after settling in the city, and became

better known through socializing with some of the best-selling authors of his day, including

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who described Barr as having a “violent manner, a wealth of strong

adjectives, and one of the kindest natures.”

15

Barr’s 1892 story titled “The Doom of London”

provides a chilling fictional account of a disastrous London fog. His story is narrated by an

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

14

James Russell Lowell, Letters, ed. by Charles Eliot (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, and Company,

1904), 215.

15

Corton, London Fog: The Biography, 99.

10

old man in the future (mid 20

th

century) who reflects on the most catastrophic of London fogs

that wiped out almost the entire population of London in November at the end of the 19

th

century.

16

The narrator was fortunate enough to have a respirator, and thus managed to escape

the asphyxiation in a fog that enveloped the metropolis. Before divulging the full story on this

apocalyptic fog, the narrator takes a moment to recognize that London fogs “differed from all

others” and that fogs were so common in London, especially in winter, that no one particularly

paid attention to them.

17

In the section of the story titled “Why London, Warned, Was

Unprepared,” the narrator compares the destruction of London to Pompeii, and contemplates a

rather haunting truth: just as the inhabitants of Pompeii were so accustomed to the eruptions of

Vesuvius that they gave little consideration to the possibility of their city being destroyed by a

storm of ashes and an overflow of lava, so too were the people of London unprepared for a

catastrophe from their fog.

18

In Barr’s prophetic story, London’s doom comes from thousands of domestic

chimneys that burned coal “for the purpose of heating rooms and of preparing food.”

19

The

black smoke emitted from chimneys remained trapped in London’s wet, cold air for seven

days. The narrator describes the fog as beginning on a Friday, and seeming not “to have

anything unusual about it” when it began, but by the seventh day the newspapers were “full of

startling statistics” yet none of the significance fully realized.

20

Barr’s writing makes the link

between coal smoke from domestic chimneys and the destruction of the metropolis undeniably

apparent, and much like Barr’s story, the weather of the week leading into the 1952 fog would

be relatively good, but conditions would deteriorate rapidly. As a closer look into the 1952

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

16

Robert Barr, “The Doom of London,” in The Face and the Mask (Urbana: Project Gutenberg, 2004)

17

Barr, “The Doom of London”

18

Barr, “The Doom of London”

19

Barr, “The Doom of London”

20

Barr, “The Doom of London”

11

fog will reveal, his story is eerily exact in some of its conditions and only sixty years ahead of

its time.

12

Chapter II: Britain’s Shift to Coal and Early Air Pollution Monitoring

Coal was the key differentiator to England’s economic development for the past two

centuries. England’s heavy reliance on coal can be traced back most significantly to the

period of the Industrial Revolution, which ushered in a new age in which coal became the

dominant source of heat energy throughout the nineteenth century. Historian E.A. Wrigley

convincingly makes the argument that Britain’s Industrial Revolution hinged on the use of

coal as an energy source that enabled England to escape the constraints of an organic economy

and overcome the Malthusian trap.

21

He argues that the shift to coal was the linchpin that

provided for positive feedback in the economy and allowed for sustained economic growth in

England.

22

The burning of coal powered the steam engines which the British used in factories,

mines, and locomotives. The adoption of steam power allowed for greater output in factories

overall, and in particular the greater production of iron and steel enabled the creation of a

national rail network that reinforced coal’s dominance by allowing its improved transport.

Urban areas, particularly London, were the concentrated sites of Britain’s coal

consumption and subsequent smoke production. The increase in the burning of coal from the

beginning of the nineteenth to the turn of the twentieth century was more than tenfold, with

Britain only burning about 15 million tons of coal in 1800.

23

Throughout the course of the

nineteenth century coal had become such a part of the way of life that by 1913, over 183

million tons were burned in Britain, with over 15 million tons of coal burned in London

alone.

24

While coal use was not new—Londoners had been adopting coal as a principal

source of heat since the thirteenth century— the increased scale of its use was quite the

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

21

E.A. Wrigley, Energy and the English Industrial Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 2010), 10.

22

Wrigley, Energy and the English Industrial Revolution, 11.

23

Peter Thorsheim, Inventing Pollution: Coal, Smoke, and Culture in Britain since 1800 (Athens: Ohio

University Press, 2006), 4.

24

Thorsheim, Inventing Pollution, 4.

13

phenomenon.

25

As Wrigley points out, much of this increased scale was fueled by, and in turn

continued to fuel, industrial production in a positive feedback loop.

The Industrial Revolution set in motion a substantial change in which coal became

inseparable from British life. Coal was the energy source to be used for any adaptable

purpose, and cities in particular were the loci for smoke pollution. The ever greater industrial

reliance on coal in turn catalyzed and bolstered the use of coal for domestic purposes. As more

and more coal was being sought out and extracted, its extraction process improved, and its

transportation facilitated through the railways, its use for fires in the home became all the

more accessible and common. Industrialization also resulted in greater levels of urbanization

and substantial population growth in cities, with London increasing from approximately one

million inhabitants in 1800 to over six million the following century.

26

This increased

crowding meant a greater concentration of coal smoke from the millions of domestic fires.

One London visitor in the 1830s even described his view of the city as a “dense canopy of

smoke that spread itself over her countless streets and squares, enveloping a million and a half

human visitors in murky vapour.”

27

Though Britain’s reliance on coal was historically tied to industrialization, it is

important to make the distinction that industrialization was not the immediate or outright

culprit in the incidence of the 1952 fog. Industrialization should not be left out of the

narrative, since it is where the roots of Britain’s shift to coal lies, but there is particular

significance in the fact that the 1952 fog occurred in London. Whereas the smoke pollution of

cities like Manchester, Leeds, and Birmingham was synonymous with industrialization,

London’s terrible fogs were the products of domestic consumption.

28

In 1952, London was

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

25

Thorsheim, preface to Inventing Pollution

26

Thorsheim, Inventing Pollution, 5.

27

Thorsheim, Inventing Pollution, 5.

28

Jesse Taylor, The Sky of Our Manufacture – the London Fog in British Fiction from Dickens to

Woolf (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2016), 2.

14

the world's biggest city and nearly all of its 8 million inhabitants used open coal fires.

29

In the

case of the 1952 fog, the house chimney was the more dangerous enemy, not the factory

chimney.

For most of the nineteenth century, scientists, engineers, and other specialists regarded

the highly visible emissions from the tall smokestacks of industrial towns as the chief cause

for problems associated with pollution.

30

The problems of industrial towns were significant,

and Dicken’s description of a fictional place like Coketown in his novel Hard Times (1854),

deserves to be taken as a stand-in for real life industrial towns of the era. As Dickens writes,

Coketown was a “blur of soot and smoke, now confusedly tending this way, now that way,

now aspiring to the vault of Heaven, now murkily creeping along the earth…that showed

nothing but masses of darkness—Coketown in the distance was suggestive of itself, though

not a brick of it could be seen.”

31

The pollution from factories made Coketown both literally

and figuratively shrouded in darkness, yet the real-life Coketowns of the industrial north were

part of an understood British identity. The poor living conditions of these areas went

unreformed for decades because coal smoke pollution was seen as the necessary byproduct of

Britain’s industrial success. Urban centers like Manchester were the vortices of production

and pollution that kept the nation running strong. Any movement to control smoke needed to

be a movement to control coal use and thus a potential threat to the British economy. London

was not a Coketown, yet experienced the brunt of the issues associated with pollution in the

North. Industrial cities like Manchester were supposed to have removed the problem from the

city center, fulfilling John Evelyn’s original dream. The problem of coal burning in London

fell to the homes fires, yet recognition of the severity and significance of this remained

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

29

“60 years since the great smog of London - in pictures,” The Guardian, December 5, 2012

30

Stephen Mosley, “‘A Network of Trust’: Measuring and Monitoring Air Pollution in British Cities,

1912-1960,” Environment and History, Vol. 15, No. 3 (2009): 275.

31

Charles Dickens, Hard Times (London: Bradbury & Evans, 1854), 131.

15

nebulous given that the link between coal smoke and the industrial economy was firmly

established.

Campaigns to Control Domestic Smoke

By the 1880s, the British public gained further awareness of the damage that the

smoke emissions from private homes caused to human health. This was in large part thanks to

the adamant campaigning of Francis Albert Russell, son of the former Prime Minister Lord

John Russell, whose influential publication London Fogs (1880) claimed that the smoke from

more than a million domestic chimneys, in combination with prolonged fogs, had choked to

death some 2,000 Londoners during late January and early February 1880, primarily due to the

exacerbation of pre-existing lung conditions.

32

Russell argued that Londoners were willing to

tolerate this “preventable evil” because a smoke-filled fog “performed its work slowly, made

no unseemly disturbance, and took care not to demand its hecatombs very suddenly or

dramatically.”

33

Though Russell was right in assigning much of the smoke pollution to

domestic sources, he used largely subjective evidence to argue his point and did not have

enough meteorological backing to support his claims.

34

For instance, Russell strongly

believed that the major contributions of smoke were from the domestic sector since he

observed that there were more fogs on Sundays and holidays than on working days.

35

These

observations were based more on his personal memory than on adequate data, though his

focus on the domestic side was certainly not misguided. Russell’s pamphlet was significant in

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

32

Mosley, “‘A Network of Trust,’” 275.

33

Stephen Mosley, “A Disaster in Slow Motion: The Smoke Menace in Urban-Industrial Britain,” in

Learning and Calamities: Practices, Interpretations, Patterns, eds. Heike Egner, Marén Schorch, and

Martin Voss (New York: Routledge, 2015), 102.

34

Mosley, “‘A Network of Trust,’” 275.

35

Brimblecombe, The Big Smoke, 114.

16

its widespread readership in Victorian London, comparable to the impact of Rachel Carson’s

Silent Spring in our own time.

36

Without reliable statistical information on the sources of urban air pollution, it was

difficult for reformers to make a strong case for political action that would interfere with an

individual’s entitlement to have an open coal fire in the home. Though publications like

Russell’s London Fogs propelled the domestic side of the issue to the forefront of the

Victorian press, public confidence was difficult to win. Even the Builder, a prominent journal

that was very supportive of the smoke abatement movement, mistrusted the evidence that was

gathered by the disparate investigations of private individuals.

37

Smoke abatement societies

like London’s Coal Smoke Abatement Society and the Smoke Abatement League of Great

Britain worked to raise awareness of the problems through exhibitions, public lectures, and

extensive pamphleteering, though many of their efforts were localized and limited.

38

Efforts

of smoke abatement groups brought the issues to the public’s attention. Nevertheless,

reformers struggled to bridge the credibility gap that existed in the public conscious. This

problem of credibility stemmed not only from the empiricist outlook of public professionals,

who wanted more comprehensive statistical data, but also from the general public opinion that

activists were an unconsolidated group of cranks unnecessarily stirring up trouble.

Well into the twentieth century, Ernest Simon, the Chairman of the Smoke Abatement

League of Great Britain, voiced the same concerns of prejudice that the anti-smoke activist

was “almost universally regarded as an amiable and unpractical faddist” and that to solve this

perception problem, the enthusiastic propagandist efforts of the abatement campaign needed to

“be replaced by research, by scientific method, by helpful technical advice, and by education

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

36

Brimblecombe, The Big Smoke, 114. !

37

Mosley, “‘A Network of Trust,’” 276.

38

Mosley, “A Disaster in Slow Motion: The Smoke Menace,” 103.

17

of both the manufacturer and of the public.”

39

Though smoke abatement groups worked

continuously to change public perceptions of coal smoke as something inevitable to something

preventable, its associations with wealth creation, employment, and home comfort were

difficult to break.

40

Anti-smoke activists did not provide enough scientific data to convince

the public toward their understanding of the air quality issue.

41

Parliamentary Efforts around Smoke

Public perception of domestic coal smoke made national reform a low priority, and

very little public persuasion amounted by the time the issue was brought before Parliament

with the Public Health (Smoke Abatement) Bill of 1926. The work of smoke abatement

groups was significant in spurring this Parliamentary consideration, yet the bill proved to be a

feeble piece of legislation. In the House of Commons, Sir Arthur Holbrook argued strongly

for the need to handle the domestic side of the issue, emphasizing to his fellow MPs:

“…we must make a start somewhere. There can be no harm whatever in

asking builders who erect houses to take some precaution to check the exit

of the smoke which is doing damage to property and vegetation and

human life. There is an idea that all the smoke nuisance is caused by

factories. That is not so. I have been in Manchester on a Sunday morning

when domestic fires only were alight. The damage created by such an

enormous volume of smoke as was then to be seen is almost

incalculable.”

42

Sir Holbrook’s reasoning fell largely on deaf ears, and the nation’s home fires were left

completely untouched by the provisions of the act.

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

39

E.D. Simon and Marion Fitzgerald, The Smokeless City (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1922),

1,3.

40

Mosley, “A Disaster in Slow Motion: The Smoke Menace,” 107.

41

Mosley, “A Disaster in Slow Motion: The Smoke Menace,” 104.

42

Parliamentary Debates, Lords, Public Health (Smoke Abatement) Bill Clause 1, December 6, 1926,

Vol. 200, No. 1827

18

The freedom to burn coal to keep warm was privileged as the prerogative of the

individual in their own private dwelling, and the government was unwilling to pass legislation

that would invade the Englishman’s sacrosanct right to a roaring fire. Smoke from the

traditional domestic fireplace conjured up feelings of well-being and comfort, and the

fireplace was often the hub around which family life revolved. The open fire was considered

such an essential part of the national home that attempts to abolish it were simply out of the

question.

The open coal fire was thought to offer restorative capabilities for the family, and

though associations of comfort for the domestic hearth were present in earlier periods, they

became intensified during the war years and in post-war society.

43

The nation was encouraged

to “Keep the Home Fires Burning” as the 1914 patriotic song by Novello and Ford goes;

indeed the widespread popularity of the song alone reflects the position of coal fires in the

cultural mindset of the early twentieth century.

44

The domestic hearth came to symbolize the

home fires of the nation, and one of its greatest advocates was George Orwell, who considered

the fire as an essential value of British society. In a column in the Evening Standard, Orwell

writes that for “a room that is to be lived in, only a coal fire will do” and that subsequently

“the survival of the family as an institution may be more dependent on it than we realise.”

45

To Orwell, the coal fire encouraged sociability and was therefore a pivotal aspect of family

life, with a gas or electric fire “a dreary thing by comparison.”

46

He recognized the downsides

of the coal fire—the dirtiness and the trouble of pollution—yet they were “comparatively

unimportant if one thinks in terms of living and not merely of saving trouble.”

47

Coal fires

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

43

Lynda Nead, “‘As snug as a bug in a rug’: post-war housing, homes and coal fires,” Science Museum

Group Journal, December 6, 2017

44

Nead, “‘As snug as a bug in a rug’”

45

Nead, “‘As snug as a bug in a rug’”

46

Nead, “‘As snug as a bug in a rug’”

47

Brimblecombe, The Big Smoke, 162.

19

were part of an English “chain of being” symbolic both of the individualized family home and

of the nation, that seemed impossible to break.

48

Though many understood that the smoke from coal fires assisted in poisoning others

outside the home, the public viewed the idea of switching to gas inside the home as

impracticable on account of supply, cost, and unfamiliarity. Fear of being poisoned by a gas

fire in one’s own home was a substantive threat in the public imagination.

49

Smoke abatement

still largely seemed the concern of the industrialists and the intelligentsia, not of the general

public.

50

The Public Health (Smoke Abatement Bill) of 1926 therefore kept its focus on

industrial production only, tightening the regulation of industrial emissions through steeper

fines and expanding the definition of ‘smoke nuisance’ to include soot, ash, and non-black

smoke.

51

Keeping the focus on industrial production was not an entirely misplaced effort, yet

the legislation largely ignored and thus perpetuated the preconditions of the 1952 disaster.

Smoke abatement activists forced the debate once again in Parliament in 1931, and

similarly the issue of public opinion came to the fore. Lord Parmoor put forth his view that

real reform and modification of atmospheric pollution would not be possible “until public

opinion is further educated in the right direction” and that the “great difficulty” of this issue

remained the “prejudice of the ordinary man in favour of burning coal upon the open

hearth.”

52

In evaluating the progress of the 1926 Public Health Act, Lord Newton also noted

its ineffectiveness, particularly in Section V of the Act, which made enforcement of regulation

by local authorities unnecessarily difficult in its framing of by-laws, and in his mind, rendered

implementation “unworkable.”

53

According to Lord Newton, the Ministry of Health needed to

do more to encourage local authorities to promote smoke abatement. Key voices within the

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

48

Nead, “‘As snug as a bug in a rug’”

49

Brimblecombe, The Big Smoke, 165.

50

Brimblecombe, The Big Smoke, 162.

51

Mosley, “‘A Network of Trust,’” 291.

52

Parliamentary Debates, Lords, Smoke Abatement, April 28, 1931, Vol. 80, No. 909

53

Parliamentary Debates, Lords, April 28, 1931

20

House of Lords were keen to tout public ignorance yet engaged in no discussion of ways to

shift public opinion. Smoke nuisance remained a local nuisance rather than a national one.

In the 1931 House of Lords debate, the MPs agreed that domestic hearths were the real

offenders and were considerably worse in combustion compared to industrial furnaces, and

this less complete combustion ultimately made for greater levels of tar and soot.

54

It was not

simply the numbers of individuals burning coal fires in open grates, but the fact that the

domestic grates caused greater damage in terms of each ton burned. Lord Cozens-Hardy also

expressed the point that this imperfect combustion of coal in domestic grates and the

subsequent waste of fuel made for economic loss to the nation, and that it could therefore

potentially be good business to encourage the use of electric heating or gas heating.

55

He even

went so far as to suggest a slight remission of income tax in the case of houses in which there

were no bad smoke-producing appliances.

56

His suggestion was not a palatable one, and it

was quickly passed over for talk of the overall expense of switching to gas.

Britain was in the thick of economic depression, and encouraging the individual

consumer to make the switch to gas in the home was out of the question in this political

moment. In such an economic downturn, the 1931 Labour government faced political danger

in going after the ‘ordinary working man,’ and encouraging a shift away from coal use in the

home would have been precisely the disruption that the government was unwilling to

entertain. The Labour government made promises in favor of miners during the 1929 general-

election campaign and had a vested interest in the coal industry’s profitable reorganization.

57

Fulfilling these promises, the government passed the Coal Mines Act of 1930 to protect

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

54

Parliamentary Debates, Lords, April 28, 1931

55

Parliamentary Debates, Lords, April 28, 1931

56

Parliamentary Debates, Lords, April 28, 1931

57

Arthur F. Lucas, “A British Experiment in the Control of Competition: The Coal Mines Act of

1930,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 48, No.3 (1934): 420.

21

miners’ wages and introduce a system of quotas in the mining industry.

58

The Labour

government had no intention to attack coal, hence matters with smoke nuisance were largely

left to local politics.

The London press periodically alerted the public to the connection between domestic

coal fires and atmospheric pollution, though public persuasion was slow to build. Even before

the passage of the 1926 Public Health Act, The Daily Telegraph had published an article that

tied kitchen chimneys to the bad fogs in London.

59

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s,

newspaper articles called attention to the fact that the burning of coal in domestic grates was

responsible for “hours of sunshine lost and fogs created” as well as the “loss of millions of

pounds yearly, bad health, and soot-laden buildings with a dingy appearance.”

60

Despite

growing awareness of the link between the domestic hearth and air pollution, it was difficult to

break the image of the grand old English custom, bound up in sentimentality and nostalgia. In

the minds of most of the British public, the resulting air pollution from domestic coal grates

made for soot covered buildings, had negative impact on vegetation, and contributed to the

London fogs that to many were part of the common occurrence of living in London, but no

urgency existed in the matter. Though the issue was addressed in Parliament using the

terminology of public health, domestic chimney smoke was not widely viewed as detrimental

to health—it was a ‘nuisance’ rather than an emergency, viewed as a necessary consequence

of affordable home heating with aesthetic repercussions.

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

58

The Coal Mines Act of 1930 also had provisions related to hours of work and settlement of labor

disputes. The Labour Party sought to suppress internal competition of the coal industry in the hope

that prices could be maintained at a more profitable level. For our purposes, a diagnosis of the troubles

of the British coal mining industry is not necessary, but it is important to recognize the Labour Party’s

role and the extent to which the coal industry’s organization was dependent on Labour’s involvement.

59

“London Fogs, Kitchen Chimneys to Blame,” The Daily Telegraph, Tuesday June 19, 1923, Issue

21265, p. 6, The Telegraph Historical Archive, accessed Jan. 11, 2019

60

“The Domestic Grate,” The Daily Telegraph, Wednesday Feb. 6, 1929, Issue 23007, p. 11, The

Telegraph Historical Archive, accessed Jan. 11, 2019

22

The Public Health Landscape

To understand the public mindset leading into the 1952 disaster, a useful

contextualization is to look at the perception of another issue that today seems inseparable

from public health: cigarette smoking. According to current British public health expert and

historian Virginia Berridge, cigarette smoking was not even a part of the British public health

agenda until the 1950s.

61

The notion of long-term “risk” in relation to lung cancer was not yet

widely acknowledged, and any sort of central publicity approach to tackle cigarette smoking

would involve asking people to curtail a deeply embedded cultural habit, not unlike reliance

on domestic coal grates.

62

The initial response to the link between smoking and lung cancer

was also conditioned by the financial importance of tobacco and the close role of the British

tobacco industry with government.

63

It was not until the 1960s that smoking was redefined as

a public health issue, and with this redefinition eventually came a rise of new ideology that

stressed individual responsibility for healthy lifestyle and behaviors.

64

During the beginning of the twentieth century, cigarette smoking and air pollution both

needed the adoption of a stronger public health lens, and the parallels between these two

issues help to illuminate general public attitudes toward health. Though it is easy to see these

two issues today as essential pieces of the public health landscape, is it only in the 1950s and

onward that these issues started to have a national public health framework, let alone be tied to

notions of individual responsibility. Public reception of emerging scientific knowledge

around the health concerns of smoking and air pollution was a slow process. A poignant

illustration of this can be seen through a conversation about coal in Sam Selvon’s novel, the

Lonely Londoners, which traces the experiences of black immigrants in the mid 1950s:

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

61

Virginia Berridge, “Smoking and the New Health Education in Britain 1950s-1970s” American

Journal of Public Health, Vol. 95, No. 6 (2005): 956.

62

Berridge, “Smoking and the New Health,” 957.

63

Virginia Berridge, “The Policy Response to the Smoking and Lung Cancer Connection in the 1950s

and 1960s, The Historical Journal, Vol. 49, No. 4 (2006): 1185.

64

Berridge, “Smoking and the New Health,” 956.

23

“‘Tanty, you wasting too much coal on the fire,’ Tolroy say.

‘Boy, leave me alone. I am cold too bad.’

Tanty put more coal on the fire.

‘You only causing smog,’ Tolroy say.

‘Smog? What is that?’

‘You don’t read the papers? Tolroy say. ‘All that nasty fog it have

outside today and you pushing more smoke up the chimney. You

killing people.’

‘So how else to keep warm?’ Tanty say.”

65

This question of “how else to keep warm” was indeed the question that needed

answering, yet the question itself reflects more than just a public awareness issue. As medical

experts conducted more research and published more medical reports throughout the 1950s,

Britain saw the formation of a public health “policy community” that weakened political

considerations and counterbalanced the priorities of industry.

66

In the cases of tobacco and

coal, the electoral dangers of intervening in popular mass habits necessitated evidenced-based

policy through strong networks of public health research. For tobacco, a major turning point

would come with the Royal College of Physicians’ 1962 Smoking and Health report, while for

coal, it was the aftermath of the 1952 fog and the findings of the committee assigned to

investigate the incident where the initiations of a new style of public health commenced, as

risky behavior among individuals slowly became a matter for government.

67

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

65

Sam Selvon, The Lonely Londoners (London: Penguin Books, 2006), 57.

66

Berridge, “The Policy Response to the Smoking,” 1185.

67

Berridge, “The Policy Response to the Smoking,” 1201.

24

Chapter III: From London Particular to Deadly Phenomenon

The 1952 Fog as It Occurred

When the fog enveloped London from December 5

th

- 9

th

1952, it certainly caught the

public’s attention, though not immediately as a matter of public health. For those five days

London was in chaos: the blanket of sulfurous fog was so dense that visibility was less than

half a metre.

68

The fog plunged London into such a sooty darkness that some individuals died,

not from lung problems, but because they fell into the Thames and drowned because they

could not see the river.

69

London transport was virtually shut down, with nearly all buses out

of action. The London Underground was still running, but severely affected by the resulting

congestion: on December 8

th

around 3,000 people queued for tickets for the Central line at

Stratford in the evening.

70

Officials even cancelled the football match at Wembley

Stadium—the first time the stadium had closed since its 1923 opening.

71

The cover of the fog

also allowed for a rise in footpad crime and burglaries, and Scotland Yard reported more

robberies than would have been likely in an evening without the fog.

72

The fog completely

disrupted daily life, yet when the air finally cleared, most Londoners resumed life as normal,

assuming the turmoil was over and having no idea the number of lives cost.

73

Since no computing shortcut for analyzing health data existed at the time, some delay

in appreciating the scale of death associated with the fog was unavoidable. Ten weeks after the

1952 fog, the General Register Office finally published its calculation of the excess deaths

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

68

“60 years since the great smog of London - in pictures.” The Guardian. December 5, 2012

69

“60 years since the great smog,” The Guardian

70

“1952: London Fog Clears after Days of Chaos,” BBC on this Day, December 9, 1952, accessed Jan.

10, 2019, http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/december/9/newsid_4506000/4506390.stm

71

“1952: London Fog Clears,” BBC on this Day

72

“1952: London Fog Clears,” BBC on this Day

73

“Fourth Night of Fog Chaos in London,” The Daily Telegraph, Tuesday December 9, 1952, Issue

30400, p. 6, The Telegraph Historical Archive, accessed Jan. 11, 2019

25

with the estimate of 4,000 lives, relying principally on hospital records.

74

Though this number

was a steep figure, Donald Acheson, a resident medical officer at the time of the fog at the

Middlesex Hospital on Goodge Street (who later served as Chief Medical Officer of the

United Kingdom from 1983-1991) believes the number was likely even higher. He suspects

that given the extreme lack of visibility in the streets, more people died at home, without help,

than in the hospital.

75

Though there was certainly pressure on hospital beds during the fog,

and the national statistics would come to reflect this, we must also consider the large number

of those who were likely horribly affected by the fog but not included in the national statistics.

In the months following the disaster, the British press began to circulate the scale of damage

done to health. As the national figure of 4,000 deaths gained currency in the press it also

served as the impetus for a political response.

The British government was initially reluctant to accept the fact that so many people

had died from breathing dirty air. In the House of Commons debate on air pollution in

January 1953, there seemed little enthusiasm on the part of the government for new

legislation.

76

The Minister of Housing at the time, Harold Macmillan, drew attention to the

powers of local government authorities to enforce smoke abatement and expressed the view

that no “further legislation [was] needed at present.”

77

Macmillan stressed to his fellow MPs

the “broad economic considerations which have to be taken into account and which it would

be foolish altogether to disregard.”

78

Macmillan’s broad economic considerations were consequential: Britain faced a war

debt of more than £31 billion, as well as growing expenses for what was becoming the Cold

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

74

Roy Parker in “The Big Smoke: Fifty years after the 1952 London Smog,” seminar held 10

December 2002 (Centre for History in Public Health, 2005): 16.

75

Donald Acheson, in “The Big Smoke: Fifty years after the 1952 London Smog,” seminar held 10

December 2002 (Centre for History in Public Health, 2005): 22.

76

Parliamentary Debates, Commons, 5th series, January 27, 1953, Vol. 510, No. 829

77

Parliamentary Debates, January 27, 1953

78

Parliamentary Debates, January 27, 1953

26

War.

79

Food rationing in Great Britain did not end completely until 1954, and this context

inevitably affected the government’s handling of fog.

80

Tied up in this was also the matter

that to raise foreign exchange to pay off debts, the British government was selling cleaner

burning coal reserves to U.S. and European businesses and keeping dirtier coal for use at

home.

81

The National Coal Board, a government-run monopoly, struggled to meet consumer

demand for coal after World War II. As the winter heating season began in 1952, the Coal

Board energetically encouraged household consumers to use low-quality (and highly

polluting) “nutty slack” which went off the ration on December 1st of that year, whereas

ordinary coal remained subject to rationing until 1958.

82

Nutty slack was exceptionally filthy

and smoky, but in the attempt to stretch fuel supplies, the National Coal Board pushed its

advertisement as the thing that would “help to keep the home fires burning however cold and

long the winter” (see Fig. 2).

83

The tenuousness of Britain's economic situation meant that in

the immediate aftermath of the 1952 fog, the government treaded carefully in an effort to not

disrupt Britain’s war recovery. !

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

79

Devra Davis, When Smoke Ran Like Water: Tales of Environmental Deception and the Battle

Against Pollution (New York: Basic Books, 2004), 45.

80

Davis, When Smoke Ran Like Water, 45.

81

David V. Bates, “A Half Century Later: Recollections of the London Fog,” Environmental Health

Perspectives, Vol. 110, No. 12 (Dec. 2002): 735.

82

Thorsheim, Inventing Pollution, 161.

83

“Display Advertising,” The Daily Telegraph, Friday November 28, 1952, Issue 30391, p. 10, The

Telegraph Historical Archive, accessed Nov. 6, 2018

27

Fig. 2 Advertisement for Nutty

Slack, The Daily Telegraph, Friday

November 28, 1952

Making Sense of the Fog

Anonymous researchers who first analyzed the fog for the official National Health

Service investigation found that death rates did not return to normal for nearly three months

after the fog, and deaths and illness remained abnormally high until the end of March 1953.

84

Health workers understood that the problems of air pollution were significantly worse than

previously perceived, though the general public did not. As London citizens began to discern

this, a falsehood started to spread that a terrible case of influenza coincided with the timeline

of the 1952 fog, and that the flu was the real reason for the death count. It is unknown who or

what group was responsible for the circulation of this notion, but consequently the British

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

84

Davis, When Smoke Ran Like Water, 47.

28

Ministry of Health’s initial report wrongfully hypothesized the additional deaths to have been

caused by influenza.

85

No evidence to support the explanation of a deadly flu exists, but the

idea of an epidemic was more acceptable the alternative. A retrospective assessment of

mortality from the 1952 fog by environmental epidemiologists Michelle Bell, Devra Davis,

and Tony Fletcher in 2004 finds that only an extremely severe influenza epidemic could

account for the majority of excess deaths in this period.

86

Such an epidemic would have

needed to be twice the case-fatality rate and quadruple the incidence observed in general

medical practice during the winter of 1953.

87

Their reassessment shows that only a fraction of

the elevated mortality in the months after 1952 London fog can be attributed to influenza,

leaving thousands of deaths otherwise unexplained. Early government reports used December

20th, 1952 as a cut-off date and failed to attribute any deaths to pollution after it, though

mortality rates remained elevated for several months.

88

Taking into account the effects of the

fog in the months after the episode (through March 1953), Bell et al.’s retrospective findings

indicate that the mortality count would be 12,000 rather than the 4,000 generally reported for

the deaths linked directly to the fog episode.

89

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

85

Davis, When Smoke Ran Like Water, 48.

86

M. L. Bell, D. L. Davis, & T. Fletcher, “A Retrospective Assessment of Mortality from the London

Smog Episode of 1952: the Role of Influenza and Pollution,” Environmental Health Perspectives, Vol.

112, No. 1 (2004): 8.

87

Bell et al. “Retrospective Assessment,” 6.

88

Bell et al. “Retrospective Assessment,” 7.

89

Bell et al. “Retrospective Assessment,” 8.

29

Seeing through the Fog: the Reported Numbers

Two groups first to grasp the severity of the 1952 fog were the undertakers and florists,

who knew there was a problem as there became a shortage of caskets and flowers.

90

Dr. Robert Waller, who worked at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital at the time, recalls those

shortages as one of the first indications that so many people were dying.

91

He also remembers

that he couldn’t see clearly to the end of the hospital ward, not only because the ward was so

full of patients, but because the polluted air made it so difficult to see—even inside the

building.

92

Hospital admissions, pneumonia reports, and applications for emergency bed service

followed the peak of this polluted air. Reports from the medical journal, The Lancet, in

January 1953 showed that in the week ending on December 13th (about two weeks from the

start of the fog) there were 4,703 deaths in Greater London, and the Emergency Bed Service

dealt with 2,007 hospital admissions, more than double the admissions for the corresponding

week of 1951.

93

Reports of two conditions—those classified as “upper respiratory tract

affections” and “respiratory disorders” increased considerably in the weeks after the fog.

94

Another report from The Lancet in February of 1953 found that one of the most striking

features of the incident was the rapidity at which deaths started to increase during the fog

itself.

95

Even on December 5th, the first day of the fog, an increase in the number of deaths

was evident, with daily death totals mounting rapidly on the third and fourth days.

96

Though

the daily death total was in decline by December 15th, it remained almost twice as high as

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

90

“Historic Smog Death Toll Rises,” BBC News, December 5, 2002, accessed November 5, 2018

91

“Historic Smog Death Toll,” BBC News

92

“Historic Smog Death Toll,” BBC News

93

G.F. Abercrombie, “December Fog in London and the Emergency Bed Service,” The Lancet, Vol.

261, No. 6753 (January 31, 1953): 234.

94

Abercrombie, “December Fog in London”

95

W.P.D. Logan, “Mortality in the London Fog Incident,” The Lancet, Vol. 261, No. 6755 (February

14, 1953): 336.

96

Logan, “Mortality in the London Fog Incident,” 338.

30

before the fog began (see Fig. 3).

97

These medical journal reports made the correlation

between fog and death rate undeniable.

Fig. 3

Mortality in the London Fog,

The Lancet, February 14,

1953, p. 338

No immediate outcry followed the 1952 episode; if anything, public reactions could

be characterized as strangely calm.

98

The frequency with which Londoners saw serious fogs

can help to explain the initial apathetic acceptance. Newspapers devoted considerable

attention to the fog as it was occurring, but initial reports said little of the effect on health.

99

Though the 1952 fog certainly lasted longer than previous ones, public concern became

palpable when the fog’s lasting assault on health became more discernible. The rise of

statistical reports in the aftermath of the fog spurred unrest among the public. Here the press

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

97

Logan, “Mortality in the London Fog Incident,” 338.

98

J.B. Sanderson, “The National Smoke Abatement Society and the Clean Air Act (1956),” Political

Studies Vol. 9, No. 3 (October 1961): 243.

99

Thorsheim, Inventing Pollution, 163.

31

was key: The Manchester Guardian reported the fog during its occurrence in December as the

“Third Day of a London Particular,” but by the end of January 1953, as death tolls were

coming to light, reported it as “Worse than 1866 Cholera.”

100

Toward a Recognition of Crisis

The shift in public mindset away from the familiarity of accustomed fogs and toward

recognition of disaster became apparent as more of the nation referred to the 1952 episode as

‘smog.’ The notion of smog was not new however; scientist Henry Antoine Des Voeux,

honorary treasurer of the Coal Smoke Abatement League, devised the term in 1904 to call

attention to the smokiness of London's fogs. Des Voeux wanted to apply the name smog to

“what is known as the ‘London particular,’” to inform that public that it “consists much more

of smoke than true fog.”

101

Though the word “smog” was a valuable addition to the political

vocabulary of smoke abaters, it did not widely catch on as a term in London until after the

1952 disaster.

102

Though true London fog was always a combination of smoke and fog, what

Des Voeux called “smog,” the widespread adoption of the term hinged on the 1952 disaster.

Today, the primary name given to this event is “Great Smog of London” or the “Great Smog

of 1952,” yet this terminology is retrospectively applied.

By November 1953, almost a year after the horrific fog, London’s press regularly

referred to smog rather than fog. The increased adoption of smog as a term correlated to the

acknowledgement of the extreme death tolls. An article from The Daily Telegraph even

reported death rate calculations in line with Bell et al.’s present day reassessment of the death

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

100

“Third Day of a London Particular,” The Manchester Guardian, December 8, 1952, Proquest

Historical Newspapers; “Worse than 1866 Cholera,” The Manchester Guardian, December 31, 1953,

Proquest Historical Newspapers

101

Christine Corton, London Fog: The Biography (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015), 27.

102

Sanderson, “National Smoke Abatement,” 246.

32

toll, proposing “12,000, Not 4,000 Killed by London Smog.”

103

Smog made headlines

because it seemed impossible that London’s historic fog could be responsible for this level of

atrocity. The transition from fog to smog marked a linguistic departure representative of a

shift in collective consciousness from the notion of fog as a tolerable phenomenon to instead a

significant danger to be eliminated.

As Londoners prepared for the winter ahead, newspapers reported on the distribution

of protective measures like smog masks and goggles, which were even termed “smoggles.”

104

Though smog masks were arguably a paltry tactic, the national insistence on their use

confirmed the reality of London’s killer smog. No longer would Londoners be expected to

hold handkerchiefs or cloths to their mouths while travelling through fog—now smog masks

were the required response.

Physicians and ministers recognized smog masks as a feeble measure of protection

with limited value, as both groups realized that the true danger came from the sulfur dioxide

fumes, and smog masks did not offer any substantial protection against gaseous contents.

105

Lord Amulree held up a smog mask before the House of Lords and gave his opinion on their

inadequacy, stating that a mask:

“is to prevent (to use a rather vulgar thought) the surgeon from being

forced to spit into the wound when he is talking, or something like that.

Masks are perfectly all right for that kind of thing, but I doubt whether they

will be of any value in dealing with these tiny particles, which are the

really dangerous things and which can get round the corners of the mask,

and penetrate the mesh of the gauze.”

106

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

103

“12,000, Not 4,000, Killed by London Smog,” The Daily Telegraph, Nov. 12, 1953, p. 8, The

Telegraph Historical Archive, accessed Nov. 6, 2018

104

“Great Britain: Smoggles,” Time Magazine, Monday Nov. 9, 1953, accessed Nov. 6, 2018

105

“Smog Masks ‘Feeble,’” The Daily Telegraph, Thursday Nov. 19, 1953, Issue 30693, p. 9, The

Telegraph Historical Archive, accessed Nov. 6, 2018

106

Parliamentary Debates, Lords, 5th series, November 18, 1953, Vol. 184 No. 374!

33

Distressed by the lack of any comprehensive official government response, doctors still urged

Londoners to protect their lungs with sixpence worth of gauze folded into a mask to be tied

over the mouth and nose. Doctors hoped the mesh of the mask would “arrest most of the soot,

while moisture from the breath, condensed on the mask, would prevent passage of some of the

chemicals that cause lung trouble.”

107

London shopkeepers were keen to seize on the

opportunity, with reports of chemists’ shops running out of gauze.

108

One main issue,

however, was that the more efficient the mask, the more difficult it was to breathe through,

particularly in the case of bronchitis patients and those suffering from cardiac diseases, for

whom smog is especially dangerous.

109

In response to the masks, the British Medical

Association released a statement that “the whole problem of the effect of smoke on health

needs to be tackled at the source” and that the country needed clean air.

110

Smog masks were

at least a discernible start to tackling this great issue, and they served as a visual symbol of a

preventive measure.

Government Investigation

The fact that smog masks were the main government tactic by the following winter of

1953 makes it clear that government reluctance to deal with the aftermath of the 1952 disaster

was still appreciable. In a memorandum to the cabinet, dated November 18th 1953, Harold

Macmillan wrote: “Today everybody expects the government to solve every problem. It is a

symptom of the Welfare State…For some reason or another ‘smog’ has captured the

imagination of the press and the people. Ridiculous as it appears from first sight I would

suggest that we form a committee. We cannot do very much, but we can seem to be very

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

107

“Great Britain: Smoggles,” Time Magazine

108

“Fog Masks May be Too Easy: Ministry Suggests Alternatives,” The Daily Telegraph, Thursday

Oct. 29th, 1953, Issue 30675, The Telegraph Historical Archive, accessed Nov. 6, 2018

109

“Fog Masks May be Too Easy,” The Daily Telegraph

110

“Is ‘Smog’ Mask under Health Service,” The Daily Telegraph, Saturday Nov. 14, 1953, Issue

30689, p. 7, The Telegraph Historical Archive, accessed Nov. 6, 2018

34

busy—and that is half the battle nowadays.”

111

Macmillan himself acknowledged the way in

which the psychological underpinnings of smog’s conception kept the issue at the forefront of

politics. Though he mentions the Welfare State with sarcastic connotation, he is right to call

attention to its role in shaping the public’s expectations.

After the Second World War, the introduction of the Welfare State imposed a stronger

sense of national responsibility for the health. The formation of the National Health Service

under the Welfare State also meant greater acceptance of financial burdens on the

government for illness prevention.

112

The Welfare State helped to generate the national

consensus that the obligation to deal with matters of health fell to the government. Once the

1952 fog became ‘smog,’ i.e. the public understood it as a public health crisis, the expectation

that government would act was irreversible. Though Macmillan still sought to balance this

against considerations of Britain’s war debt, the actions and legacy of the Welfare State

primed the government with a willingness to intervene on matters of health to a newfound

degree.

While much is owed to the influence of British press as the forces on the ground that

spurred public understanding of smog, Labour MP Norman Dodds also deserves credit for

continually pressing the matter in Parliament. Five months after the fog episode, he fervently

urged the formation of an investigative committee to cover the 1952 disaster. While

addressing the House of Commons in May 1952, Dodds brought up a fog in Donora,

Pennsylvania, which killed twenty people in 1948, and made reference to how the “whole

[American] nation was shocked when 20 persons died and several more became ill,” yet the

British government had still refrained from a public inquiry into the heavy death toll.

113

“America usually does things in a bigger way than we do,” he stated, “but I wonder what they

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

111

Mick Hamer, “Ministers Opposed Action on Smog,” New Scientist (January 5, 1984): 3.

112

!Corton, London Fog: The Biography, 332.!

113

!Parliamentary Debates, Commons, 5th series, May 8, 1953, Vol. 515, No. 846 !

35

are thinking about 6,000 English people dying in Greater London alone.” Dodds made his

remarks with vigor and urgency, declaring that if nothing was to be done, “We may even

once again in the London streets hear the cry, ‘Bring out your dead.’” His rhetoric was hard

to ignore, and he was one of the key players that forced the attention of the British

government.

After a buildup of pressure from the British press, the public, and individuals like

Norman Dodds, the government officially formed the Committee on Air Pollution (called the

Beaver Committee for its chairman, Sir Hugh Beaver) in July 1953. It was a considerably

strong group whose mandate was to conduct a comprehensive study of “the nature, causes

and effects of air pollution, and the efficacy of present preventive measures.”

114

The Beaver

Committee’s final report summarized much of what was known about the effects of air

pollution at the time, condemning its harm on public health while also estimating that the

pollution caused £150 million in damage to textiles, metals, and buildings each year, and that

it cost at least another £100 million in time lost to illness and transportation delays.

115

The

report made it clear that air pollution did not just cost lives, but also cost a great deal to the

British economy. The committee’s work drew together much of the thinking on smoke

abatement that had accumulated throughout the previous decades and treated air pollution as

a public health crisis that required a campaign as vigorous as the one waged by nineteenth-

century sanitary reforms for safe water.

116

The economic and health costs of air pollution

were too dire to be ignored, and not just in the context of the 1952 smog episode. The

Committee was therefore careful to frame its findings in a way that did not simply make for a

short-term magnification of the overall problem of air pollution.

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

114

Parliamentary Debates, Commons, 5th series, July 21, 1953, Vol. 518, No. 201

115

Thorsheim, Inventing Pollution, 175.

116

Brimblecombe, The Big Smoke, 169.

36

In reflecting on the work of the committee, Chairman Hugh Beaver noted: “we

expressly avoided basing our arguments on the danger to health of particular incidents, such

as the London smog of 1952. Not that we minimized that catastrophe in any way, but we felt

that undue emphasis on it, would distract attention from the fact that damage to health and

danger to life were going on all over the country, all the time, year in and year out.” All of

Britain, as he put it, constituted a “single permanently polluted area.”

117

Though based in

London, the entire committee met with local authorities, businesses, and nongovernmental

organizations in many of the most polluted places in Britain, including Manchester, Glasgow,

and Birmingham.

118

The problem required more than damage control: it needed an extensive

and comprehensive national strategy.

The Clean Air Act of 1956

The 1952 fog had made the dangers of polluted air obvious and unavoidable,

therefore action for clean air would receive broad enough public support that both the

Conservative and Labour parties supported air pollution reform in the 1955 election.

119

Building upon the findings of the Beaver Committee, the government passed the Clean Air

Act of 1956, which prohibited “dark smoke” from chimneys, and limited smoke, grit, and

dust from both industrial and domestic sources.

120

This legislative piece makes the act

something of a milestone, since it was the first legal provision to control domestic smoke.

The desire for cleaner air undoubtedly had to be supported by the public at large, for that

desire meant a degree of infringement on public liberty which would not have been tolerated

twenty years earlier. Here a new measurement for defining “dark smoke” became crucial: the

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

117

Thorsheim, Inventing Pollution, 174.

118

Thorsheim, Inventing Pollution, 175.

119

Brimblecombe, The Big Smoke, 169.

120

“Clean Air Act 1956 Chapter 52,” The National Archives, July 5, 1956, accessed November 8, 2018

37

Clean Air Act prohibited any smoke which appeared to be as dark or darker than shade two

on the Ringelmann Chart (see Fig. 4).

121

With previous public health legislation, determining

what one would have defined as “black smoke” proved a challenge and enabled too many

exemptions within the legislation.

122

With a regularized scale for measuring the density and

opacity of smoke, the inclusion of the chart fulfilled an important need in smoke abatement

work and allowed for an established standard of compliance.!

Fig. 4

The Ringelmann Chart for measuring

the density/opacity of smoke,

in Brimblecombe, The Big Smoke, p.

170

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

121

Brimblecombe, The Big Smoke, 170.

122

Brimblecombe, The Big Smoke, 164.

38

The Clean Air Act enabled local government to set up smoke control areas (often called

smokeless zones) and within these areas the emission of dark smoke was prohibited unless it

was the result of burning an authorized fuel which was specified in the regulations and

included solid smokeless fuels.

123

Local cooperation was therefore essential, as the creation

and enforcement of smokeless zones was the responsibility of local authorities. The National

Smoke Abatement Society suggested the establishment of smokeless zones in the 1930s, but

war delayed such implementation.

124

The industrial center of Manchester was one of the first

places to utilize the strategy with the Manchester Corporation Act (which passed in 1946 but

went into effect in 1952).

125

From 1952-53 the act so greatly reduced smoke pollution in the

target area in Manchester that it became a prime example for the Beaver Committee’s

recommendations. Such was the influence of the Manchester Corporation Act that the Clean

Air Act of 1956 stipulated identical fines for non-compliance of its conditions.

126

In looking at the Manchester experience, the Beaver Committee recommended the

formation of smoke control areas in the most highly polluted parts of Britain—industrial and

residential places where large quantities of coal were consumed within a small area and

which experienced frequent natural fogs.”

127

The committee also considered alternative

energy sources to replace coal for domestic heating. Although gas and electricity offered

advantages, few people in the mid 1950s seemed willing to switch entirely, and the

committee was eager to propose reforms that would not be too expensive. The Beaver

Committee therefore recommended that coal be phased out by coke, a solid smokeless fuel

made from coal. Converting a typical coal-burning fireplace to burn coke cost between £3

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

123

“Clean Air Act 1956 Chapter 52”

124

Robert Heys, “The Clean Air Act 1956,” British Medical Journal, Vol. 345, No. 5751, August 24,

2012, accessed November 2, 2018

125

Heys, “Clean Air Act”

126

Heys, “Clean Air Act”

127

Thorsheim, Inventing Pollution, 176.

39

and £5, but converting it to burn gas cost between £10 and £20.

128

The Beaver Committee

also proposed that the national government reimburse owners or occupiers in smoke control

areas 50 percent of the cost of replacing old household coal-burning appliances with ones that

could use smokeless fuel, but the government’s bill reduced the size of the subsidy requiring

owners or occupiers of private houses to pay 30 percent of the cost, with local authorities

paying another 30 percent, and the national government contributing the final 40.

129

Here

the government had the opportunity to make clean air an explicit measure of national policy

through subsidies, yet maintained financial caution.

The Clean Air Act largely responded to the Beaver Committee’s suggestions, yet the

act itself was not a radical piece of legislation. The hand of the Federation of British Industry

may have been at work in the drafting of the bill, as the act gave industry seven years before

full compliance was required. By 1960, eighty-five of the most polluted localities in Britain

had not even developed a plan to deal with their smoke—twenty-one localities denied that

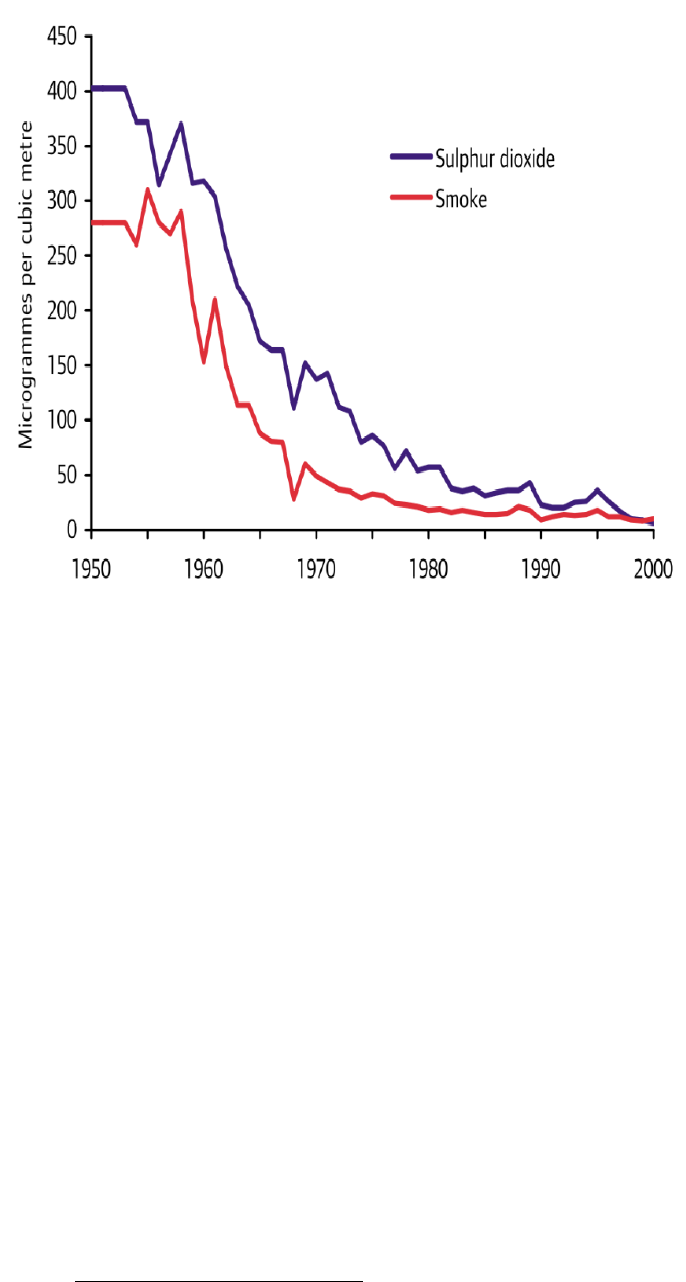

they had a problem, and thirty were reluctant to prohibit the use of coal because some of their