48 Finance & Development December 2015

Offering

citizenship

in return for

investment is

a win-win for

some small

states

“A

RE you a Global Citizen? Let us

help you become one.” You may

have seen such an advertise-

ment in an in-ight magazine

designed to lure some business class passen-

gers, largely from less-developed economies,

into acquiring a passport that can smooth

their entry at the border of their next desti-

nation. A whole new industry of residence

and citizenship planning has emerged over

the past few years, catering to a small but rap-

idly growing number of wealthy individuals

interested in acquiring the privileges of visa-

free travel or the right to reside across much

of the developed world, in exchange for a sig-

nicant nancial investment.

Judith Gold and Ahmed El-Ashram

A Passport of

CONVENIENCE

A growing phenomenon

e rapid growth of private wealth, especially

in emerging market economies, has led to a

signicant increase in auent people inter-

ested in greater global mobility and fewer

travel obstacles posed by visa restrictions,

which became increasingly burdensome

aer the terrorist attacks of September 11,

2001. is prompted a recent proliferation

of so-called citizenship-by-investment or

economic citizenship programs, which allow

high-net-worth people from developing or

emerging economy countries to legitimately

acquire passports that facilitate international

travel. In exchange, countries administering

such programs receive a signicant nancial

investment in their domestic economy. Also

contributing to the rapid growth of such

programs is the pursuit of political and

economic safe havens, in a deteriorating

geopolitical climate and amid increased

security concerns. Other considerations

include estate and tax planning.

Economic citizenship programs are

administered by a growing number of

small states in the Caribbean and Europe.

Their primary appeal is that they confer

citizenship with minimal to no residency

requirements. Dominica, St. Kitts and Nevis,

and several Pacific island nations have had

such programs for years: the St. Kitts and

Nevis program dates back to 1984. More

recently, a number of new programs have

been introduced or revived, including by

Antigua and Barbuda, Grenada, and Malta,

with St. Lucia the most recent addition to the

list. While some of these programs have been

in place for years, they have only recently

seen a substantial increase in applicants, with

a corresponding surge in capital inflows.

Similarly, economic residency programs

were recently launched across a wide range

of (generally much larger) European coun-

tries, including Bulgaria, France, Hungary,

Ireland, the Netherlands, Portugal, and

Finance & Development December 2015 49

Spain. Almost half of EU member states now have a dedi-

cated immigrant investor route.

Also known as golden visa

programs, these arrangements give investors residency

rights—and access to all 26 Schengen Area countries, which

have agreed to allow free movement of their citizens across

their respective borders—while imposing minimal resi-

dency requirements (see table). Although these programs

differ in that one confers permanent citizenship while the

other provides just a residency permit, they both allow

access to a large number of countries with minimal resi-

dency requirements, in return for a substantial investment

in their economies (see Chart 1).

In contrast, some advanced economies, such as Canada,

the United Kingdom, and the United States, have had immi-

grant investor programs since the late 1980s or early 1990s,

offering a route to citizenship in exchange for specific invest-

ment conditions, with significant residency requirements. In

2014, Canada eliminated its federal immigrant investor pro-

gram, but the provinces of Quebec and Prince Edward Island

continue to run a similar scheme that leads to Canadian citi-

zenship. And the United Kingdom and the United

States continue to run and expand their programs.

The cost and design of the programs vary

across countries, but most involve an up-front

investment, in the public or the private sector,

combined with significant application fees and

an amount to cover due diligence costs. The pro-

grams in the Caribbean allow for either a large

nonrefundable contribution to the treasury or

to a national development fund, which finances

strategic investment in the domestic economy, or

an investment in real estate (which can be resold

after a specified holding period). Other pro-

grams provide the option to invest in a redeem-

able financial instrument, such as government

securities. In Malta, the program requires contri-

butions in all three investment routes.

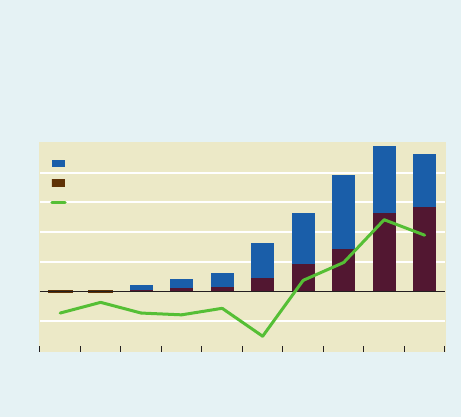

Economics of citizenship

e inows of funds to countries from these pro-

grams can be substantial, with far-reaching mac-

roeconomic implications for nearly every sector,

particularly for small countries (see Chart 2).

Inows to the public sector alone in St. Kitts and

Nevis, which has the most readily available data,

had grown to nearly 25 percent of GDP as of 2013.

Antigua and Barbuda and Dominica have also ex-

perienced signicant inows. In Portugal, inows

under the country’s golden visa program may ac-

count for as much as 13 percent of estimated gross

foreign direct investment inows for 2014; in

Malta, total expected contributions to the general

government (including the National Development

and Social Fund) from all potential applicants—

which are capped at 1,800—could reach the equiv-

alent of 40 percent of 2014 tax revenues when all

allocated passports are issued.

Gold, corrected 10/26/2015

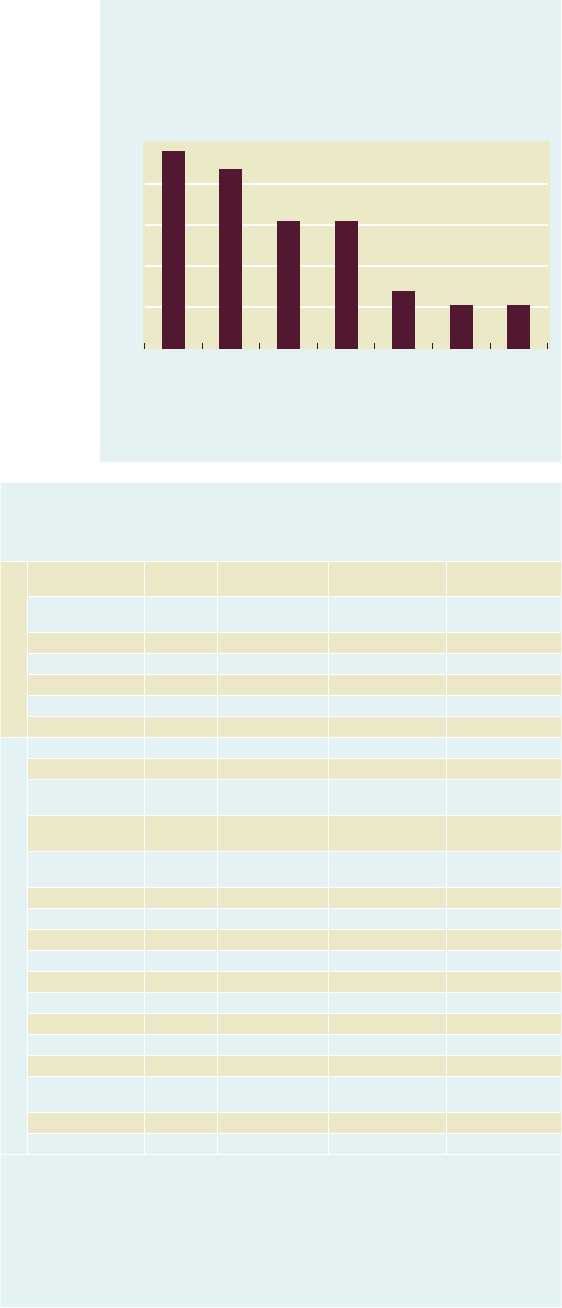

Chart 1

Pick a country, any country

Among the countries offering citizenship programs, Maltese and

Cypriot passports offer visa-free access to the most countries.

(number of countries)

Source: Henley & Partners Visa Restriction Index 2014.

Note: Ranking reects the number of countries to which the country’s passport offers

visa-free access. The program is not yet launched in St. Lucia.

Malta Cyprus Antigua and St. Kitts St. Lucia Dominica Grenada

Barbuda and Nevis

70

90

110

130

150

170

The price of citizenship

The conditions for acquiring a passport via economic citizenship/residency vary by

country.

Citizenship Programs

Country

Inception

Year

Minimum

Investment

1

Residency

Requirements

2

Citizenship

Qualifying Period

3

Antigua and

Barbuda 2013 US$250,000

5 days within a

5-year period Immediate

Cyprus 2011 €2.5 million No (under revision) Immediate

Dominica 1993 US$100,000 No Immediate

Grenada 2014 US$250,000 No Immediate

Malta 2014 €1.15 million 6 months 1 year

St. Kitts and Nevis 1984 US$250,000 No Immediate

Residency Programs

Australia 2012 $A 5 million 40 days/year 5 years

Bulgaria 2009 €500,000 No 5 years

Canada

4,5

Mid-1980s Can$800,000

730 days within a

5-year period 3 years

Canada—Prince

Edward Island Mid-1980s Can$350,000

730 days within a

5-year period 3 years

Canada—Quebec

5

N.A. Can$800,000

730 days within a

5-year period 3 years

France 2013 €10 million N.A. 5 years

Greece 2013 €250,000 No 7 years

Hungary 2013 €250,000 No 8 years

Ireland 2012 €500,000 No N.A.

Latvia 2010 €35,000 No 10 years

New Zealand N.A. $NZ 1.5 million 146 days/year 5 years

Portugal 2012 €500,000 7 days/year 6 years

Singapore N.A. S$2.5 million No 2 years

Spain 2013 €500,000 No 10 years

Switzerland N.A.

Sw F 250,000/

year

No 12 years

United Kingdom 1994 £1 million 185 days/year 6 years

United States 1990 US$500,000 180 days/year 7 years

Sources: Arton Capital; Henley & Partners; national authorities; UK Migration Advisory Committee; and other immigration

services providers.

1

Alternative investment options may be eligible.

2

Explicit minimum residency requirements under immigrant investor program; residency criteria to qualify for citizenship

may differ.

3

Including the qualification period for permanent residency under residency programs.

4

Program suspended since February 2014.

5

Although not specific to the immigrant investor program, retaining permanent residency requires physical presence of 730

days within a five-year period.

50 Finance & Development December 2015

The macroeconomic impact of economic citizenship pro-

grams depends on the design of the program, as well as the

magnitude of the inflows and their management. The fore-

most impact is on the real sector, where inflows can bolster

economic momentum. Programs with popular real estate

options generate an inflow similar to that of foreign direct

investment, boosting employment and growth. In St. Kitts and

Nevis, inflows into the real estate sector are fueling a construc-

tion boom, which has pulled the economy out of a four-year

recession—to a growth rate of 6 percent in 2013 and 2014, one

of the highest in the Western Hemisphere. The rapid increase

in golden visa residency permits in Portugal, which has issued

more than 2,500 visas since the program’s inception in October

2012, has reportedly bolstered the property market, leading to

a steep rise in the price of luxury real estate.

However, a large and too rapid influx of investment in the

real estate sector could lead to rising wages and ballooning

asset prices, with negative repercussions on the rest of the

economy. And the rapid expansion in construction could

erode the quality of new properties and eventually under-

mine the tourism sector, since most of the developments

include (or are repurposed for) tourist accommodations.

Moreover, inflows under these programs are volatile

and particularly vulnerable to sudden stops, exacerbating

small countries’ macroeconomic vulnerabilities. A change

in the visa policy of an advanced economy could suddenly

diminish the appeal of these programs. It’s conceivable that

advanced economies could act together to suspend their

operations, triggering a sudden stop. Increasing competi-

tion from similar programs in other countries or a decline

in demand from source countries could also rapidly reduce

the number of applicants.

If they are saved rather than spent, inflows from these pro-

grams can substantially improve countries’ fiscal performance.

In St. Kitts and Nevis, budgetary revenues from the program

boosted the overall fiscal balance to more than 12 percent of

GDP in 2013, one of the highest in the world. But these inflows

can also present significant fiscal management challenges,

similar to those caused by windfall revenues from natural

resources (see “Sharing the Wealth” in the December 2014

F&D). Such revenues can lead to pressure for increased gov-

ernment spending, including higher public sector wages, even

though the underlying revenues may be volatile and difficult

to forecast. The resulting increase in dependence on these

revenues could lead to sharp fiscal adjustments or an acute

increase in debt, if or when the inflows diminish.

A country’s external accounts are also significantly

affected by large program inflows. The budgetary revenues

can improve the country’s current account deficit, and sub-

stantially so if they are saved, and the capital account can be

strengthened by transfers to development funds and higher

foreign direct investment. But increased domestic spending

as a result of higher government expenditures and investment

will substantially boost imports, particularly in small open

economies, offsetting some of the initial improvement in the

balance of payments. Risks to the exchange rate and foreign

currency reserves are also magnified as these inflows become a

major source of external financing. In addition, rising inflation

from economic overheating can cause the real exchange rate

to appreciate, lowering the country’s external competitiveness

over the long run.

Large program inflows can also boost bank liquidity,

especially if the bulk of the budgetary receipts are saved in

the banking system. At the same time, they can threaten

financial stability in small states. While some increase in

liquidity may be welcome, large accumulation of program-

related deposits presents new financial risks, reflecting

small banking systems’ limited and undiversified options

for credit expansion. Risks to financial stability may be

magnified if banks face excessive exposure to construction

and real estate sectors already propped up by investments

from the economic citizenship program. In that case, a

sharp decline in program inflows could prompt a correction

in real estate prices, with negative implications for banks’

assets, particularly if supervision is weak.

Another challenge is the risk to governance and sustainability.

Cross-border security risks associated with the acquisition of a

second passport are likely to be the main concern of advanced

economies. Reputational risks are also magnified: weak gov-

ernance in one country could easily spill over to others, since

advanced economies are less likely to differentiate between citi-

zenship programs. In addition, poor or opaque administration

of programs and their associated inflows—including inadequate

disclosure of the number of passports issued, revenues collected,

and mechanism governing the use of generated inflows—could

prompt strong public and political resistance, complicating, or

even terminating, these programs. Programs have indeed been

shut down in the past as a result both of security concerns and

domestic governance issues.

Weeding out the risks

Country ocials can implement policies to reduce and con-

tain the risks small economies face from large economic citi-

zenship program inows while allowing their economies to

capitalize on the possible benets.

Gold, corrected 10/26/2015

Chart 2

A big boost

St. Kitts and Nevis’s economic citizenship program accounts for

signicant inows.

(percent of GDP)

Sources: National authorities; and IMF staff estimates.

2005 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14

–10

–5

0

5

10

15

20

25

Contributions to national development fund

Contributions to government

Fiscal balance

Finance & Development December 2015 51

Prudent management of government spending has an

important role in containing the impact of these inflows on

the real economy, but it should be accompanied by sufficient

oversight and regulations to pace inflows, particularly to the

private sector. For example, annual caps on the number of

applications or the size of investments would limit the influx

of investments to a country’s construction sector. A regula-

tory framework for the real estate market would reduce risk

and limit potentially damaging effects of price distortions

and segmentation in the domestic property market as a result

of investment minimums imposed by these programs.

Changing key parameters of the program can also be an

effective way to redirect investments to the public sector,

allowing countries to save the resources for future use and to

invest in infrastructure.

Saving is a virtue

Large fiscal revenue windfalls tend to trigger unsustainable

expansions in expenditure that leave the economy exposed

if the revenue stream dries up. Given the potentially vola-

tile nature of these inflows, program countries—and small

economies in particular—need to build buffers by saving

the inflows and reducing public debt where it is already

high. Prudent management of citizenship inflows would

allow for a sustainable increase in public investment and

accommodate what economists call countercyclical spend-

ing—spending when times are bad—and relief measures

in the face of natural disasters. As in resource-rich econo-

mies, managing large and persistent inflows is best under-

taken via a sovereign wealth fund. This would help deal

with fluctuations in program revenues and stabilize the

impact on the economy, possibly also providing scope for

intergenerational transfers.

In any case, all fiscal revenue from economic citizen-

ship programs, whether application fees or contributions

to development funds, should be channeled through the

country’s budget to allow for proper assessment of the fis-

cal policy stance and avoid complications in fiscal policy

implementation. In particular, development funds financed

by economic citizenship programs should have their role

properly defined and their operations and investments fully

integrated in the budget.

Effective management of inflows, combined with prudent

fiscal administration, will also reduce risk to the external

sector, by containing the expansion of imports, limiting the

rise in wages and the real exchange rate, and accumulat-

ing international reserves—to serve as a buffer in case of a

sharp slowdown in program receipts. Strengthening bank-

ing sector oversight is also needed to moderate risks arising

from the rapid influx of resources to the financial system.

Caps on credit growth, restrictions on foreign currency

loans, or simply tighter capital requirements may be needed

to dampen the procyclical flow of credit.

Managing a reputation

Preserving the credibility of the economic citizenship program

is perhaps the most critical challenge. A rigorous due diligence

process for citizenship applications is essential to preclude po-

tentially serious integrity and security risks. And a compre-

hensive framework is needed to curtail the use of investment

options as routes for money laundering and nancing criminal

activity. Such safeguards are integral to the success of economic

citizenship programs. A high level of transparency regarding

economic citizenship program applicants will further enhance

the program’s reputation and sustainability. is could include a

publicly available list of newly naturalized citizens. Complying

with international guidelines on the transparency and exchange

of tax information would reduce the incidence of program mis-

use for purposes of tax evasion or other illicit activities and min-

imize the risk of adverse international pressure. Countries with

similar programs should also collaborate among themselves and

with concerned partner countries to improve oversight and en-

sure that suspicious applicants are identied.

Moreover, to help garner necessary public support for

these programs, the economic benefits should accrue to

the nation as a whole. They should be viewed as a national

resource that may not be renewable if the nation’s good name

is tarnished by mismanagement. A clear and transparent

framework for the management of resources is necessary,

including a well-defined accountability framework with

oversight and periodic financial audits. Information on the

number of people granted citizenship and the amount of rev-

enue earned—including its use and the amount saved, spent,

and invested—should be publicly available.

The ever-surprising effects of globalization have given rise

to a new dynamic whereby passports can carry a price tag.

Economic citizenship programs facilitate travel for citizens of

emerging and developing economy countries in the face of

growing travel restrictions and are an unconventional way for

some countries, particularly small states, to increase revenue,

attract foreign investment, and bolster growth. Keeping these

programs from being shut down calls for efforts to ensure

their integrity, and the security and financial transparency

concerns of advanced economies must be duly addressed.

Small states offering these programs must develop macroeco-

nomic frameworks to deal with the potential volatility and

inflationary impact of the inflows, by saving the bulk of them

for priority investment in the future and by pacing and regu-

lating their flow into the private sector.

■

Judith Gold is a Deputy Division Chief and Ahmed El-Ashram

is an Economist, both in the IMF’s Western Hemisphere

Department.

is article is based on a 2015 IMF Working Paper, “Too Much of a Good

ing? Prudent Management of Inows under Economic Citizenship

Programs,” by Xin Xu, Ahmed El-Ashram, and Judith Gold.

A rigorous due diligence process for

citizenship applications is essential.