%.0')!2!2%-)4%01)26%.0')!2!2%-)4%01)26

#(.+!0.0*1%.0')!2!2%-)4%01)26#(.+!0.0*1%.0')!2!2%-)4%01)26

.#).+.'6(%1%1 %/!02,%-2.&.#).+.'6

".02).-!-$!/)2!+3-)1(,%-2(!-')-'22)23$%1!-$".02).-!-$!/)2!+3-)1(,%-2(!-')-'22)23$%1!-$

%,.'0!/()#!+-83%-#%1%,.'0!/()#!+-83%-#%1

1(+%6./%./(!,

.++.52()1!-$!$$)2).-!+5.0*1!2(22/11#(.+!05.0*1'13%$31.#).+.'6 2(%1%1

!02.&2(%.#).+.'6.,,.-1

%#.,,%-$%$)2!2).-%#.,,%-$%$)2!2).-

./(!,1(+%6./%".02).-!-$!/)2!+3-)1(,%-2(!-')-'22)23$%1!-$%,.'0!/()#!+

-83%-#%1(%1)1%.0')!2!2%-)4%01)26

$.)(22/1$.).0'

()1(%1)1)1"0.3'(22.6.3&.0&0%%!-$./%-!##%11"62(%%/!02,%-2.&.#).+.'6!2#(.+!0.0*1%.0')!

2!2%-)4%01)262(!1"%%-!##%/2%$&.0)-#+31).-)-.#).+.'6(%1%1"6!-!32(.0)7%$!$,)-)120!2.0.&

#(.+!0.0*1%.0')!2!2%-)4%01)26.0,.0%)-&.0,!2).-/+%!1%#.-2!#21#(.+!05.0*1'13%$3

ABORTION AND CAPITAL PUNISHMENT: CHANGING ATTITUDES AND

DEMOGRAPHICAL INFLUENCES

by

ASHLEY POPHAM

Under the Direction of Dr. James Ainsworth

ABSTRACT

This project analyzes the changing views on abortion and capital punishment and how

opinions have changed over the past 35 years. This is an analysis of how different backgrounds and

demographic factors affect people‘s standpoints toward these two practices.

INDEX WORDS:

Abortion, Capital punishment

ABORTION AND CAPITAL PUNISHMENT: CHANGING ATTITUDES AND

DEMOGRAPHICAL INFLUENCES

by

ASHLEY POPHAM

A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of

Master of Arts

in the College of Arts and Sciences

Georgia State University

2008

Copyright by

Ashley Popham

2008

ABORTION AND CAPITAL PUNISHMENT: CHANGING ATTITUDES AND

DEMOGRAPHICAL INFLUENCES

by

ASHLEY POPHAM

Committee Chair:

James Ainsworth

Committee:

Erin Ruel

Phillip Davis

Electronic Version Approved:

Office of Graduate Studies

College of Arts and Sciences

Georgia State University

December 2008

iv

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank my parents for instilling in me the confidence that was necessary to

embark on this journey. My mother‘s assurance that I can accomplish whatever I set out for, her

constant encouragement, and my father‘s lifelong advice to find my calling has guided me to this

milestone. I thank my husband Cameron for always believing in me and giving his daily support

from beginning to end. Finally, I would like to thank the chair of committee, Dr. James

Ainsworth, not only for being a great mentor, but for being the inspirational teacher and

motivator whose influence played a large part in where I am today.

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

iv

LIST OF TABLES

vii

LIST OF FIGURES

viii

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

1

The Politics of Life

3

CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW

8

The History of Attitudes toward Abortion

8

Arguments for and against Abortion

11

Group Perceptions toward Abortion

15

Race and Attitudes toward Abortion

15

Gender and Attitudes toward Abortion

15

Age and Attitudes toward Abortion

16

Religion and Attitudes toward Abortion

17

Educational Attainment and Attitudes toward Abortion

18

The History of Attitudes toward Capital Punishment

19

Arguments for and against Capital Punishment

22

Group Perceptions toward Capital Punishment

29

Race and Attitudes toward Capital Punishment

29

Gender and Attitudes toward Capital Punishment

31

Religion and Attitudes toward Capital Punishment

32

Collective Views toward Abortion and Capital

Punishment

33

vi

Theory of Spatial Clustering and Cognitive Bundling

37

CHAPTER 3: METHODOLOGY

40

Data

40

Dependent Variables

43

Independent Variables

44

Analysis

47

CHAPTER 4: RESULTS

48

Bivariate Analysis

48

Multinomial Logistic Regression Analysis

58

CHAPTER 5: CONCLUSION

74

REFERENCES

80

vii

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1: Variable Descriptions

67

Table 2-A: Multinomial Logistic Regression Results: Conservative (Relative to

Liberal)

68

Table 2-B: Multinomial Logistic Regression Results: Anti-Life (Relative to Liberal)

69

Table 2-C: Multinomial Logistic Regression Results: Pro-Life (Relative to Liberal)

70

Table 3-A: Multinomial Logistic Regression Results: Anti-Life (Relative to

Conservative)

71

Table 3-B: Multinomial Logistic Regression Results: Pro-Life (Relative to

Conservative)

72

Table 4: Multinomial Logistic Regression Results: Pro-Life (Relative to Anti-Life)

73

viii

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1: Two-by-Two

3

Figure 2: Race

49

Figure 3: Gender

50

Figure 4: Religiosity

51

Figure 5: Years of Education

52

Figure 6: Political Views

53

Figure 7: Region

54

Figure 8: Year Surveyed

55

Figure 9: Age (when survey was taken)

56

Figure 10: Birth Cohort

57

1

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

My study will examine attitudes toward abortion and capital punishment and how these

opinions have changed over time. Generally, liberals approve of abortion and disapprove of the

death penalty. Conservatives typically object to the legalization of abortion and promote the

practice of capital punishment. I will analyze how different backgrounds and demographic

factors affect respondents‘ standpoints toward these two practices, both of which have been

highly debated as either acceptable or non-acceptable life-ending practices. This study is

important because, unlike other literature, it will incorporate both topics at once. The

simultaneous study of abortion and capital punishment provides a new framework for how these

attitudes are related. In addition, this study differs from other studies because I will track both

these issues over time. I will utilize existing data from the General Social Survey to analyze

trends related to these themes. The GSS is ideal for my study because data regarding abortion

and capital punishment attitudes have been collected over a long period of time (nearly every

year since 1972). This creates a useful way for me to measure the existence of fluctuations in

these attitudes.

Abortion and capital punishment attitudes are of interest for several reasons. Both are

among the most discordant debates in the United States in the early part of the new millennium.

While the two acts themselves are quite different, the ―moral‖ issues inherent in each can be seen

as related. I have chosen these particular issues (as opposed to another similar attitudinal object

such as suicide) because with both of these acts, an individual is conceivably imposing their

belief on a life (or potential life) other than their own. The lack of literature on the

abortion/death penalty combination makes this study unique. Past studies have focused on

2

abortion and capital punishment opinions separately whereas this project will analyze the ideas

simultaneously.

This study will explore an array of opinions on abortion and capital punishment, and will

focus on what characteristics shape people‘s opinions and how these attitudes have changed over

time. Specifically, I have chosen to test how the following concepts relate to attitudes toward

capital punishment and abortion: race, gender, age, religion, education, political views, and

region of the United States; these have all been collected as a part of the General Social Survey.

The main question I will answer through my research is What factors influence people’s

attitudes toward abortion and capital punishment and how have those opinions fluctuated over

time? Therefore, I will study two variables, attitudes toward capital punishment and attitudes

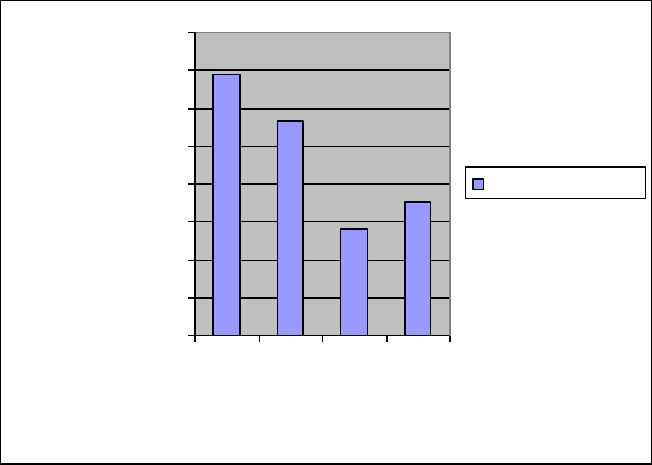

toward abortion. Within this larger dependent variable, Figure 1 shows four types of people

categorized: those that fall within the Anti-Life category, the Liberal category, the Conservative

category, or the Pro-Life category. Those within the Anti-Life category would not generally be

opposed to either abortion or capital punishment. They would be considered to hold a

―consistent‖ opinion toward life in both instances. Individuals whose attitudes fall within the

Pro-Life category would value life in both situations (abortion and capital punishment). Again,

this would be the other category in which the group members held consistent opinions regarding

life in general. In the other two categories, ―Liberal‖ and ―Conservative,‖ group members hold

inconsistent views toward life. They value life in one instance and disregard life in the other

instance. Due to the nature of these four non-rankable dependent variables, multinomial logistic

regression is used as my analytical strategy. My main dependent variable is the combination of

these four categories.

3

Capital Punishment

Abortion

Figure 1: Two-by-Two

In order to study the similarities and differences between the topics of abortion and the

death penalty, it is important to have a solid understanding of how these debates have fluctuated

over time, and how and why potential regulations for and against these acts began. I will give a

historical overview of both debates, but will begin by describing a recent case that illustrates the

complexities and inconsistencies within these issues.

The Politics of Life

In 2003, Paul Jennings Hill, an excommunicated U.S. Presbyterian minister and anti-

abortion activist was put to death in Florida. He was sentenced to execution by lethal injection

for shooting and killing an abortion doctor and his clinic escort. Hill claimed that he felt no

remorse for his actions, and that he expected ―a great reward in Heaven‖. At the age of 17, Hill

had converted to fundamentalist Christianity. As pastor of a Pensacola church, he became deeply

involved in the anti-abortion movement. On the morning of July 29, 1994 he fired a 12-gague

shotgun at Dr. John B. Britton and his bodyguard, James H. Barret outside the Ladies Clinic in

Favor

Oppose

Favor

Anti-Life

N=7,501

Liberal

N=2,416

Oppose

Conservative

N=10,716

Pro-Life

N=3,881

4

Pensacola, Florida killing both. Earlier that morning he had practiced with the shotgun at a local

shooting range. After the shooting, he noticed that Britton was still alive and he fired five more

rounds until all movement stopped. He laid the shotgun down and walked out toward the street

with his hands by his side, awaiting arrest (Church and State October 2003). Florida law ruled

that he should be sentenced to death and he was the first person in the United States to be

executed for killing a physician who provided abortions. This case gives a compelling example

of the extreme variation of attitudes toward life and death issues such as abortion and capital

punishment.

Over time, the United States has experienced significant uproar when passionate parties

from both sides of these debates feel others should share in their beliefs and opinions and should

live their lives accordingly, supporting the cause. It is certainly interesting how much fluctuation

has occurred in the political arena in the past. Analyzing these trends is an important step in

understanding major aspects of the two debates.

In 1995, Pope John Paul II described ―culture of life‖ as, ―respect for human life from the

first moment of conception until its natural end (Coburn 2004).‖ Tom Coburn, a former

Republican candidate for the U.S. senator for Oklahoma once said that ―what we need is some

good old-fashioned common sense in Washington‖ and has implied that he favors the death

penalty for doctors that perform abortions (Coburn 2004). President George W. Bush claims he

strongly supports the ―culture of life‖ idea in which ―it should be our goal as a nation to build a

culture of life, where all Americans are valued, welcomed and protected.‖ During the presidential

election of 2000, the ―culture of life‖ entered mainstream U.S. politics when George W. Bush

expressed his goal of promoting a ―culture of life‖. During the election, he suggested, ―surely

this nation can come together to promote the value of life.‖ The phrase ―culture of life‖

5

references the anti-abortion movement in the United States, which has received significant

encouragement, especially in the 2004 presidential election (Annas 2005). This term is a recent

slogan among social conservatives, including President Bush himself, who is a strong death

penalty supporter. In his State of the Union speech in 2005, Bush announced that, ―because a

society is measured by how it treats the weak and vulnerable, we must strive to build a culture of

life‖ (Schneider 2005).

The example is commonly raised that politicians who say they endorse the culture of life

are simultaneously supportive of capital punishment and war. These politically consistent but

perhaps logically contradicting attitudes have been analyzed by academics. In the situation of

abortion when the woman‘s life is at risk, philosopher and author Leonard Peikoff argues that

―sentencing a woman to sacrifice her life to an embryo is not upholding the ‗right to life‘…you

cannot be in favor of life and yet demand the sacrifice of an actual, living individual to a clump

of tissue‖ (Peikoff 2003).

Although there will realistically always be opposing views as to what behavior is right

and what behavior is wrong, law-abiding citizens are expected to accept the rules set forth by

majority rulings, which is what makes us so passionate about both of these debates. They can

potentially affect ours lives whether we like it or not. If there are any two topics that can cause

utter disagreement among people in the public sphere, abortion and capital punishment are two

issues that the public clearly feels strongly about. Therefore, these topics are also often hot topics

in political campaigns. It is important that the public be exposed to all aspects of either side of

these debates because through political processes, we put the power of life or death in the hands

of the government. The issues of abortion and the death penalty are particularly susceptible to

6

criticism on either side because they affect our most personal feelings and our private lives.

Perhaps this is why people are so sensitive about these topics.

When we speak of the ―politics of life,‖ we are describing a long continuum of attitudes

where the public sphere continually debates over major political issues such as abortion and

capital punishment. It seems when we give authorities the ability to decide what is considered

murder and what is considered having a ―right to life‖, these lines between right and wrong

become very debatable among the general public. The most debatable and, to many, the most

important of these political arguments becomes the debates having to do with how we define life

and death. Abortion and capital punishment go hand and hand in the political arena for this very

reason. They both relate to the way specific individuals view who or what deserves life and what

is most important in these situations. Some people consider abortion immoral and some do not,

just as some people consider the death penalty immoral and some do not. These issues offer a

compelling comparison. Like most other political debates, it is doubtful our society will ever

come to a universal agreement.

The political categories are often defined as follows. Political liberals tend to be pro-

choice or pro-abortion and anti-capital punishment while political conservatives tend to be pro-

life in regards to abortion and pro-death in regards to capital punishment. One would expect pro-

lifers to value life in all cases, and those that do not value life to do so in all cases but the general

public seems to be more inconsistent than would be expected. I explore an array of different

opinions on abortion and capital punishment, and focus on what characteristics shape people‘s

opinions and how these attitudes have changed over time.

7

The following sections will give an overview of the history behind abortion and capital

punishment practices in the United States and Europe. Various arguments for and against both

abortion and capital punishment will be summarized. In order to outline and compare the

characteristics of people for and against abortion and capital punishment, I will discuss the

differences in individual and group attitudes toward the two issues and show how these attitudes

have changed over time. I will begin by describing the past accounts of abortion and the concerns

that people have held which date far back in history.

8

CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW

The History of Attitudes toward Abortion

Over the last few centuries there have been major changes in attitudes toward abortion.

During the mid-thirteenth century, abortion after fetal formation was punished by law as a

homicide. The fetal formation was the point at which the fetus assumed human shape, about 40

days after conception. By the mid-seventeenth century, abortion was considered by some as a

serious misdemeanor. It began to be prohibited as a ―great misprision‖. Most literature in the

early 1800s condemned abortion, but all writers seemed to agree that a large part of the public

did not regard abortion as a terrible practice (Sauer 1974).

In the early nineteenth-century, the common law appears to have prohibited abortion after

―quickening‖, meaning the time between the 12

th

and 20

th

week of pregnancy. Quickening was

defined by the point at which the mother feels the first fetal movement. At this time, as far as

reports can show, people probably neither valued early life highly, nor held abortion before

quickening to be a violation of morality. There is a limited amount of literature in the early

1800s and it seems abortion was probably not a subject that entered the minds of most

Americans. Larger families were the norm at this time and it is doubtful that the average

American wife made much use of abortion. At this time, abortions were mostly used to end non-

marital pregnancies. The Christian view of abortion as wrong seems to have been a persuasive

informal norm, and it seems most American women had little motivation for abortion or any

other kind of fertility control (Sauer 1974).

Leading up to the mid 19th century, more women started seeking abortions. People

noticed the trend and began to attempt legal measures to try and suppress the growing number of

abortions. As manufacturing and business became more widespread, many women began to

9

think of children as expensive or burdensome. With the emergence of the women‘s rights

movement, women began to want fewer children and there became a greater need for abortion.

At this time, many medical professionals became very vocal about their opposition to terminating

pregnancies. Religious leaders were also highly vocal in their opposition and abortion was

thought of as an unacceptable means of fertility limitation even by the founders of the birth

control movement. In fact, one of the main selling points of early birth control proponents was

that it would minimize the use of abortion. In early 1846, birth control advocates thought the

contraceptive would eventually lead to the disappearance of abortion altogether (Sauer 1974).

In the late nineteenth century both England and the United States experienced a

restriction of this prohibition. The wording of these statutory provisions made clear that this law

was to protect un-born life (Keown and Phil 2006). In the United States, more dramatically than

in England, it seems this new legislation was influenced by the emerging medical profession

whose discovery that human life began at fertilization exposed the moral irrelevance of

quickening. Soon legislatures began to abolish the quickening distinction and tightened the law

in order to protect the unborn.

In 1858, the American Medical Association campaigned to criminalize abortion and

successfully made it illegal at all stages of pregnancy (Beisel and Kay 2004). The 1860s and

1870s were the peak period for concern with abortion during the nineteenth century but still in

the last decades of the century, widespread reports continued. By 1890, almost every state had

passed laws making it illegal and most gave doctors the authority to decide when abortion was

medically necessary. Many of these laws did not change until the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision

(Beisel and Kay 2004).

10

In the 1940s and 1950s abortion on demand was very much rejected but broadening the

terms of legal abortion became a respectable idea. In the 1960s, Americans increasingly began to

justify abortion on moral grounds, and the fetus was seen by growing numbers only as a

‗potential‘ human being. The idea of legalized abortion began to gain acceptance rapidly (Sauer

1974). The idea of aborting a fetus was seemed to become less taboo and more morally

acceptable. There was a gradual evolution of more permissive abortion norms that rose from the

development of low-fertility values. Modern medicine had made hospital abortion a safer

procedure than childbirth, which eliminated one of the main previous reasons for the suppression

of abortion (Sauer 1974). In addition, changes in sexual attitudes played a role in attitudes

toward abortion. Since early times, a more open discussion of all sexual matters has led to a

more open discussion of abortion. This more open-examination of abortion eventually led to

changes in the ethics and laws (Sauer 1974).

No single event has had more impact on abortion views than the 1973 U.S. Supreme

Court decision in Roe v. Wade (410 U.S. 113). In January of 1973 the Court ruled that access to

abortion during the first three months of pregnancy was guaranteed by constitutional provisions

concerning privacy. At the time of the ruling, the Court divided pregnancy into three trimesters

and ruled that abortion may not be prohibited within the first six to seven months of pregnancy

(Adamek 1994). In the United States, abortion has been highly controversial since this 1973

legalization (Sahar and Karasawa 2005).

Abortion has been common across all societies but has not been a center of attention in

political controversy and debate in all societies (Krannich 1980). For example, in Japan, abortion

faced ―essentially no moral opposition‖ as recently as ten years ago. Many societies of ancient

times did not view abortion as a bad behavior. Some refer to Japan as ―abortion heaven.‖

11

During April 2007, in an attempt to reduce cases of abandoned babies and abortions, a Japan

hospital announced that it would set up a hatch into which unwanted infants could be

anonymously dropped, at which point an alarm would sound alerting nurses that an unwanted

newborn had arrived. A nurse at the hospital reports that they place a great value on life and

want to ―widen the choices available to women (CNN.com April 5, 2007).‖ ―With no law

against abortions and no clear religious taboos in predominantly Buddhist Japan, the procedure is

readily available and widespread (CNN.com April 5, 2007).‖ According to the Health Ministry,

in 2005, more than 289,000 cases of abortion were reported, or 10.3 cases for ever 1,000 women

aged 15 to 44 (CNN.com April 5, 2007).

Arguments for and against Abortion

It is not surprising that this history of abortion has seen many arguments for and against

the highly debated act. Those in favor of legalized abortion hold strong beliefs but anti-abortion

supporters have firm opinions as well. One argument for legalizing abortion is as follows. The

implementation of laws making abortion illegal has not stopped women from having illegal

abortions. It is likely that women in our society will follow through with having abortions

regardless of what laws are attempted to enforce against them. As Richard Krannich pointed out

in his article more than twenty years ago, ―The most that can be said on the basis of available

data is that abortion in the United States certainly did not decline with the implementation of

laws and policies restricting legal access to induced pregnancy termination‖ (Krannich

1980:365). Data on the incidence of abortion for the first half of the twentieth century are scarce

but by 1970 it was estimated that 65% of all the abortions that year were illegal abortions. Exact

data on the number of illegal abortions remains unavailable (Krannich 1980). However, the

12

likelihood that women will still have abortions whether legal or not is one of the main arguments

made by pro-choice activists.

According to author David Grimes, women have always had abortions and will continue

to do so, regardless of laws, religious outlawing or social norms (Grimes et. al 2006). Of course

the ethical debate over abortion will remain, but pro-abortionists argue that having access to legal

abortion can improve health of the mother. Grimes explains that pregnancy-related deaths are

the ultimate tragic outcome of the cumulative denial of women‘s human rights. ―Women are not

dying because of untreatable diseases. They are dying because societies have yet to make the

decision that their lives are worth saving‖ (Grimes et. al 2006: 1917). Every year, approximately

19 to 20 million abortions are done worldwide by individuals who lack required skills or in

environments that do not meet medical standards, or both. Ninety seven percent of unsafe

abortions happen in developing countries. In turn, an estimated 68,000 women die as a result.

Many of these women die from hemorrhaging, infection or poisoning. Many pro-choice activists

argue that legislation of abortion on request is a necessary step that would improve women‘s

health (Grimes et. al 2006). Some even refer to the unsafe abortions as a ―silent pandemic‖ with

an urgent need to become legalized. In fact, some feel it is a pressing public health issue and a

human rights imperative. Some abortion supporters compare unsafe abortions to other global

health issues, and say that it is similar, just less visible. Grimes explains that the availability of

modern contraception can reduce the need for abortion, but it will never eliminate it (Grimes et.

al 2006). They point out that the direct costs of treating abortion complications are hard on

already impoverished healthcare systems. They refer to the access to safe, legal abortion as the

fundamental right of women (Grimes et. al 2006). ―Unsafe abortion is a persistent, preventable

pandemic‖ (Grimes et. al 2006). Legal abortion, they explain, is one of safest procedures in

13

contemporary medical practice. Proponents of abortion feel that unsafe abortion endangers

health and should receive the same approach to solution that other threats to public health receive

(Grimes et. al 2006).

Scholar and pro-life activist Raymond Adamek has discussed pro-abortion arguments in

detail. He describes the reasons some favor abortion and then goes on to argue his anti-abortion

stance. Among the reasons that are often cited as pro-abortion arguments, he describes, are as

follows: A woman has a right to control her own body (Adamek 1994). Women should be free

to choose abortion since it is safer than childbirth (Adamek 1994). Women should be free to

have legal abortions so that they are not ―forced‖ to go to ―back-street‖ abortionists (Adamek

1994). Abortion should be allowed in cases of rape or incest to spare the woman mental anguish.

Abortion is necessary to protect the physical, mental, or social health of the mother (Adamek

1994). Abortion should be allowed for the sake of the unwanted child. Strict anti-abortion laws

limit freedom, whereas lenient laws do not (Adamek 1994). Restrictive anti-abortion laws are

not effective deterrents, and thereby create disrespect for the law. Restrictive anti-abortion laws

are discriminatory. Abortion is necessary to fight the population explosion (Adamek 1994).

Adamek suggests that personal freedom can only be enhanced by helping people to

appreciate the situations they find themselves in. He explains that encouraging them to deal with

the facts is the answer, rather than abortion. This is one of the more recently cited arguments,

that which is supported by ideas of responsibility. However, there are also more primitive

notions of why abortion should be illegal. In the 1800s, James Mohr was one of the first writers

to give a detailed historical account of abortion. He wrote that it was believed that outlawing

abortion would preserve the native population. At this time in America, white Protestants were

threatened by the growing number of immigrants.

14

Many pro-lifers base their argument on the philosophy that embryos, babies, children

and adults are all stages of human life that are equally alive and have equal worth. Pro-life

advocates often claim that the fetus merits more protection than the life of the mother, and often

describe the fetus as the innocent life that has done nothing to deserve death and so must be

allowed to live. However, scholar Thomas Clark argues that in cases where a woman‘s life is at

risk, more concern must be placed on the woman and her ―fully developed capacities‖ and

―network of established relationships‖ than the fetus, an ―entity possessing neither.‖ He

describes these two stages of life as being very different and doesn‘t find it difficult to decide

which one should live should one be faced with the choice (Clark 2007).

Often cited pro-life arguments include 1) the belief that life begins at conception, 2)

social traditionalism, 3) political conservatism, and 4) all life is worth preserving. Many people

5) believe that abortion goes against God‘s rules, and it 6) devalues human life (Hess and Rueb

2005). Pro-life individuals view life as beginning at conception, whereas most pro-choice

activists define life as beginning at birth (Hess and Rueb 2005).

There are two basic schools of thought on how the public expresses their beliefs about

abortion. These are the Pro-life and the Pro-choice ideologies. Darwin Sawyer describes two

basic ideas on these beliefs. The pro-life (often anti-abortion and/or anti-choice) view

summarizes public attitudes toward life and death that come from beliefs about the morality of

ending a human life. The basic thought of those who hold the pro-choice view feel a pregnant

woman should have the ability to make the decision themselves, rather than the government

making that decision for her.

15

Group Perceptions toward Abortion

People are certainly all over the spectrum with their opinions regarding abortion. With

that said, it is important to have an understanding of how opinions can be affiliated with not only

individual characteristics, but with group perceptions as well. Factors such as race, gender, age,

religiosity and educational attainment have been found to be correlated with certain abortion

opinions. Over time, not only have fluctuations occurred amongst individual notions, but these

group notions. I will explore the characteristics of people who are in favor of abortion and

against abortion and how opinions have changed over time.

Race and Attitudes toward Abortion

Race has often been cited as a predictor of attitudes towards abortion. Using data from the

General Social Surveys, Strikler and Danigelis find that in early times, whites were more

approving of abortion than blacks but by the end of the 1980s this had reversed (Strickler and

Danigelis 2002). They also found that white women are less likely than black women to have an

abortion. Their 2002 analysis revealed that by the mid 1990s, black adults had become more

accepting of legal abortion than whites after other factors are controlled. Scott and Schuman

(1988) found that blacks are generally less likely than whites to regard abortion as important. As

an explanation, they suggest that for the black community, issues that involve racial inequalities

make abortion seem like an unimportant concern (Scott and Schuman 1988).

Gender and Attitudes toward Abortion

Analyzing a study from 1992 through 1996, Ladd and Bowman (1997) found that when

compared to men, women have more polarized views towards abortion, meaning they tend to

think that abortion should be always legal or always illegal. Men, on the other hand, had

attitudes that fell much more moderate (Ladd and Bowman 1997). However, other studies have

16

found sex to be altogether unrelated to people‘s views on abortion (Strickler and Danigelis

2002). An attitudinal study conducted by Jacqueline Scott and Howard Schuman of Michigan

University found that women feel more strongly about abortion than men. Even though men

were as likely or more likely to be pro-choice than women, women were more likely to regard the

issue as important when in comes to voting or taking social action (Scott and Schuman 1988).

A 2000 study found that adolescent males have become less approving of abortion. It

seems their feelings about the resolution of possible pregnancies are related to their individual

background as well as their family background characteristics (Boggess and Bradner 2000).

Young men in 1995 were much less likely than their 1988 counterparts to approve of abortion

(Boggess and Bradner 2000).

In her research conducted on attitudes toward abortion among college students, Barbara

Finlay (1981) found that males‘ attitudes toward abortion were simpler in structure than those of

females. It seemed females may be more inclined than men to consider humanitarian issues in

their development of abortion opinions. She tested this for attitudes toward capital punishment

and results were similar. Females were more likely to consider the question of when human life

actually begins and whether one has the right to end it (Finlay 1981).

Age and Attitudes toward Abortion

Bivariate analyses indicate that older people may be less likely than younger people to

approve of abortion rights (Ladd and Bowman 1997). This brings up another question entirely,

whether this is a period effect or simply the result of an individual growing older. This study will

test the difference between the two circumstances. In the first circumstance, the act of getting

older would influence attitudes toward abortion. In the second circumstance, being a certain age

17

during a certain period of time in history would weigh more heavily than an individual‘s age

alone.

Religion and Attitudes toward Abortion

Religion also seems to be closely intertwined with attitudes toward abortion. In the

United States, expressions of religious faith are more widespread than in other advanced

industrial nation. Faith plays an important role in shaping public policy. Therefore, religion is

concerned in understanding the causes of criminal behavior as well as how society reacts to the

behaviors it defines as illegal (Unnever, Cullen and Applegate 2005). According to author David

Garland, a professor of Christian Scriptures, ―Throughout the history of the penal practice,

religion has been a major force in shaping the ways in which offenders are dealt with.‖

Religion undoubtedly has a complex affect on abortion attitudes. Politically conservative

individuals tend to perceive pregnant woman as having more control over the unwanted

pregnancy than do political liberals (Sahar and Karasawa 2005). The Catholic Church has had a

considerable role in the pro-life view. Being Catholic has a negative effect on abortion approval,

and, as a whole, the Catholic Church has played a key role in opposing abortion rights.

Conservative Christians also tend to oppose abortion (Stickler and Danigelis 2002). The majority

of the leaders of the pro-life movement have been drawn from conservative Christian

denominations. Individuals who are unaffiliated with religion or Jewish tend to have higher

levels of support for abortion rights compared to Christians (Ladd and Bowman 1997). Buddhist

leaders generally think abortion is wrong, but they are less likely to try to influence politics than

religious leaders in the United States (Sahar and Karasawa 2005). Interestingly, studies have

shown that the denominational split between Catholics and Protestants has actually narrowed

(Ladd and Bowman 1997). Christians who feel that religion is very important to them report

18

more opposition to abortion than people who report that religion is not as important (Stickler and

Danigelis 2002).

Educational Attainment and Attitudes toward Abortion

Authors Ladd and Bowman find that educational attainment is one of the most reliable

predictions of attitudes toward abortion. Higher levels of education for both sexes predict higher

levels of support for legal abortion (Ladd and Bowman 1997). They suggest that perhaps this is

because highly educated women are more likely to hold responsibilities other than motherhood

and might feel that unwanted pregnancies could threaten their position. In addition, with an

increase in education, we also see a decline in religiosity. Some suggest that a declined

religiosity often accounts for a greater individualistic nature.

Strickler and Danigelis also find that educational attainment is one of the most reliable

predictors of individuals‘ views on abortion. They explain that highly educated women support

legal abortion because they are more likely to engage in meaningful activities other than

motherhood (Strickler and Danigelis 2002). Highly educated women have a broader view of

acceptable women‘s roles, and Strickler and Danigelis suggest that they are more likely to see

unwanted pregnancies as threatening to the woman‘s well-being.

It is evident from this literature that countless attempts have been made to link abortion

attitudes with characteristics such as race, gender, age, religiosity, and educational attainment.

While all of these factors have been thought to collectively contribute to an individual‘s attitude

toward abortion, another topic in the political sphere whose arguments may also surface from

similar aspects of our lives is the debate about capital punishment. There are many ways our

particular stance on the death penalty can be equated from our combination of the same

background characteristics. Since the first recorded case of capital punishment, there have been

19

fluctuations in attitudes similarly to the fluctuations in attitudes toward abortion. Quite similarly

to abortion, people have been expressing their opinions on capital punishment since long ago.

The History of Attitudes toward Capital Punishment

The use of the death penalty as a punishment in Europe and the United States dates as far

back as the tenth century when hanging was the most common method in Britain until the

following century when William the Conqueror would not let people be hanged or executed for

any crime except in times of war. This short-lived anti-capital punishment trend would not last

because during the sixteenth century under the rein of Henry VIII, an estimated 72,000 people

(deathpenaltyinfo.org/) were executed by methods such as boiling, burning at the state, hanging

and beheading. Throughout the next two centuries, the number of executions in Britain

continued to rise but many juries would not convict defendants unless the offense was serious

because of the severe executions styles mentioned. This soon led to reforms of Britain‘s death

penalty. However, Britain had more influence on America‘s use of the death penalty than any

other country. European settlers coming to the new world brought the practice to America and

their laws regarding capital punishment varied colony to colony.

During the eighteenth century, common methods for execution included crucifixion,

drowning, beating to death and burning alive. During these times, an abolitionist movement

emerged. A famous essay published in 1764 by European theorist Cesare Beccaria, a pioneer for

the abolition of capital punishment, suggested that there was no justification for the state‘s taking

of a life (deathpenaltyinfo.org/) . He argued that the death penalty is irrevocable and without

remedy in the case of a judicial error. Beccaria was convinced that a system with more moderate

laws would have a better influence on the character of the people, making them kinder and

gentler, therefore less prone to commit crimes (Maestro 1973). He expressed the view that any

20

killing, including executing a criminal, was an evil act, and he attempted to produce a general

attitude of greater respect for human life (Maestro 1973). This essay had a strong impact

throughout the rest of the world and soon American intellectuals were influenced and reforms

were attempted. Thomas Jefferson introduced a bill to revise Virginia‘s death penalty laws,

which suggested that capital punishment be used only for the crimes of murder and treason. The

bill was defeated by one vote. Another influence was Dr. Benjamin Rush, a signer of the

Declaration of Independence and founder of the Pennsylvania Prison Society. He challenged the

belief that the death penalty serves as a deterrent (deathpenaltyinfo.org/). He was an early

believer in the ―brutalization effect‖ and thought that the death penalty actually increased

criminal conduct (deathpenaltyinfo.org/). His interest and passion for this issue sparked his

publication of a 1792 essay entitled Considerations of the Injustice and Impolicy of Punishing

Murder by Death.

During the abolitionist movement, the state of Pennsylvania became the first state to

move executions out of the public eye and into correctional facilities. Many states were

beginning to abolish the use of the death penalty, but most states held on to it. During the Civil

War, opposition to the death penalty diminished as the anti-slavery movement became a focus.

The electric chair was introduced at the end of this century when New York built the first electric

chair in 1888 (deathpenaltyinfo.org/). At this time, death by electrocution was perceived as ―an

advance of civilization‖ and ―seemed to signify the human ability-or at least that of white

educated males- to understand supernatural forces, to conquer them, and use them for positive,

culturally beneficial effects‖ (Martschukat 2002). During the Enlightenment, the electric chair

was seen as giving humans the ability to ―subdue and control natural powers‖ and this became an

important piece of the concept of civilization (Martschukat 2002).

21

Eventually, the progressive period surfaced in the early part of the twentieth century and

certain states began to outlaw the death penalty (deathpenaltyinfo.org/). This reform did not last

long. From 1907 to 1917, six states completely outlawed the death penalty and three limited it to

the rarely committed crimes of treason and first degree murder of a law enforcement officer.

Soon, citizens began to panic about the threat of a revolution and five of the six abolitionist states

reinstated their death penalty by 1920 (Bedau, 1997 and Bohm, 1999).

From the 1920s to 1940s criminologists began to write that the death penalty was a

necessary social measure, and the use of the death penalty began to rise again

(deathpenaltyinfo.org/). During the 1930s there were more executions than in any other decade

in American history, perhaps due to the fact that Americans were experiencing the Great

Depression and Prohibition. But again, in the 1950s, the use of the death penalty dropped. It

wasn‘t until the 1960s that it was strongly suggested that the death penalty was a ―cruel and

unusual‖ punishment. Before then, the Fifth, Eighth, and Fourteenth Amendments were

interpreted as allowing the death penalty. However, in the 1960s, the Supreme Court began to

re-examine the death penalty and the way it was administered.

The United States‘ use of the death penalty has seen a gradual rise during the seventeenth,

eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. There was a peak of almost 200 executions per year in the

mid-1930s, a subsequent decline in use and finally we see a trend toward more executions in

recent years (deathpenaltyinfo.org/).

It was in 1972 that a momentous decision was made by the US Supreme Court. The trial

of Furman v. Georgia made all but a few death penalty statues in the United States

unconstitutional. When this happened, over 600 inmates that were on death row in the United

22

States were re-sentenced to life in prison. Four years later, the Supreme Court reversed this

ruling with the case of Greg vs. Georgia (Radelet and Borg 2000).

Over the past 50 years, public opinion on the death penalty has fluctuated. Support

decreased through the 1950s and until 1966, when 47% of the American public was in support of

capital punishment. Between 1982 and 2000, about 75% of the population favored capital

punishment. In a study conducted by Radelet and Borg in 2000, the vast majority of the

American public supported the death penalty, at least under some circumstances, but they add

that support for the death penalty is highly conditional. They suggest that the best data on public

support for the death penalty comes from the Gallup Polls. They point out that in 1994 support

had reached 80 percent (Radelet and Borg 2000). An article in the Economist in 2000 mentions

that Americans have always favored capital punishment by an overwhelming majority. The

article claimed that according to the 2000 Gallup Poll, support for the death penalty had dropped

to 66%, a 19-year low (Economist 2000). According to a poll by Gallup released by USA Today,

As of October 2007, 69 percent of respondents were in favor of the death penalty for a person

convicted of murder, up four points since May 2006 (Gallup/USA Today 2007).

Though the death penalty seemed to be on its way out at the end of the eighteenth century,

over two hundred years have passed and the death penalty has remained in our legal system. Not

surprisingly, and quite similarly to the abortion debate, there are countless arguments for and

against the use of the death penalty.

Arguments for and against Capital Punishment

In the 1970‘s, the main argument that death penalty supporters made was general

deterrence (Radelet and Borg 2000). In other words, offenders need to be punished in order to

discourage others from committing the same crimes. Some argue that we punish past offenders

23

in order to send a message to potential offenders. Here, people are certain if they violate laws,

they will be punished (Radalet and Borg 2000). Individuals that support the death penalty also

commonly argue that there must be consequences for the types of heinous crimes than those in

prison commit. But many in the anti-death penalty group argue that capital punishment is not

successful as a deterrent. Many researchers, such as well-known criminologists of their times,

Edward Sutherland (1925) and Thorsten Sellin (1959) have researched whether or not the death

penalty has a greater deterrent effect on homicide rates than long-term imprisonment (Bailey &

Peterson 1997, Bohm 1999, Hood 1996, Paternoster 1991, Petersom & Bailey1998, Zimring &

Hawkins 1986). Some studies have been able to find deterrent effects (e.g., Ehrlih 1975), but

these studies have been criticized (e.g., Klein et al 1978). Overall, most deterrence studies have

failed to support the hypothesis that the death penalty has a greater deterrent effect on homicide

rates than long-term imprisonment (Radalet and Borg 2000). In fact, Bailey and Peterson (1997),

two of America‘s most experienced deterrence researchers, conclude that capital punishment in

the United States is not more effective than imprisonment for deterring murder (Bailey and

Peterson 1997). Criminologists and law enforcement officials are in general agreement that

capital punishment does not seem to be cutting homicide rates any more than long term

imprisonment (Radalet and Borg 2000).

In a 1995 survey, almost 400 randomly selected police chiefs and county sheriffs from all

over the United States were asked if they thought the death penalty significantly lowered the

number of murders and results showed that one third believed it had that effect (Radelet and

Akers 1996). In fact, other opinion polls are showing that most of the American public is

agreeing with the police and sheriff study. In 1991, the Gallup Poll reported that 51% of

Americans believed the death penalty had deterrent effects, which was a drop from the 1985. In

24

1997, this number fell to 45%. These polls show that there have been fluctuations in the way the

death penalty is justified. What was once a highly cited justification for the death penalty, the

idea of actual deterrence is today losing its appeal (Radalet and Borg 2000).

Other reasons that have been suggested for why individuals are in favor of capital

punishment is their concern that crime is on the rise as well as the tendency for those who have

been personally victimized to consider themselves pro-capital punishment. Joseph Rankin, an

author that examines changing attitudes toward capital punishment, argues that it is in fact the

concern about crime that results in greater demand for harsh penalties, not personality

characteristics or personal victimizations. Rankin uses five years (1972-1976) of NORC General

Social Survey data as well as data on official violent crime rates to point out that although many

studies have found different personality associations of death penalty attitudes, these are not

necessarily precursors for short-term attitudinal changes (Rankin 1979). He argues that only

historical or period effects could explain the rise in support for capital punishment at the time of

his study. He also disputes the claim that the rise could be the result of an increase in number of

people personally victimized. By measuring anxiety scores of victimized and non-victimized

respondents, Rankin agrees that there is no relation between victimization and concern about

crime. However, he uses the example that even dramatic crimes such as robbery did not have

any long-term effects of victims‘ attitudes and behavior‖ (Rankin 1979).

Some people who are against capital punishment feel modern prisons are better than

prisons of the past, and therefore, the incidence of life without parole should be reexamined.

However, others support the incapacitation argument which suggests that we need to execute

killers in order to prevent them from killing again. This argument is based on the fact that

executed criminals will never kill again, whereas those criminals sentenced to long-term prison

25

still have that opportunity. Many feel that the incapacitation argument might have made sense in

historical times when there were no prisons that could accommodate prisoners long-term. Now,

some people feel that the heightened availability of long-term confinement could be equally

effective as capital punishment for preventing murders from repeating their crimes. Now there is

increased sentencing of ―life without parole‖ as an alternative to the death penalty (Radelet and

Borg 2000). However, most people in America do not realize this availability and highly

underestimate the amount of time people convicted of capital murders will spend in prison (Fox

et al 1991). Many proponents of the death penalty that are aware of life without parole

sentencing alternative still feel that judges will always find ways to release life-sentenced

inmates. This is an interesting paradox because the group who wishes to give the government the

ultimate power to take lives of its citizens does so because of distrust of the same government

(Radelet and Borg 2000).

The 1999 Gallup Poll found that 56% of the respondents supported the death penalty

given the alternative of life without parole. This percentage seems much less than the

―overwhelming support‖ that many people think the death penalty receives. Authors Radalet and

Borg feel that death penalty support will decrease dramatically as more Americans learn that

those convicted of capital crimes (who are not executed) will never be released from prison

(Radelet and Borg 2000). In fact, several studies have shown that support for the death penalty is

conditional to the degree at which the public is informed about the realities of how the death

penalty is administered and what alternatives are available (Vollum, Longmire, and Buffington-

Vollum 2004). The Marshall Hypothesis is one example of the belief that support for the death

penalty is based on a group of people that are simply uninformed of the realities or uneducated

about the facts (Vollum, Longmire and Buffington-Vollum 2004).

26

Another argument of those in favor of capital punishment is a monetary explanation.

―Two decades ago, some citizens and political leaders supported the death penalty as a way of

avoiding the financial burdens of housing inmates for life or long prison terms‖ (Radelet & Borg

2000:50). According to legal scholar Ernest van den Haag, ―It is not cheaper to keep a criminal

confined for all or most of his life than to execute him. He will appeal just as much as a death-

sentenced prisoner‖ (van den Haag & Conrad 1983). The 1985 Gallup report showed that 11%

of people who supported the death penalty felt that monetary costs were a big reason for their

position (Gallup Report 1985). In the last 25 years, it has become evident through research that

the modern death penalty system costs several times more than life without parole (Radelet

2000). There has been extensive research conducted in different states using different data sets

through newspapers, courts and legislatures, as well as academics (see reviews in Bohm 1998,

Dieter 1997, Spangenberg & Walsh 1989). ―Estimates by the Miami Herald are typical: $3.2

million for every electrocution versus $600,000 for life imprisonment‖ (von Drehle 1988: 1).

People against the death penalty may argue that these costs could potentially be put towards

reducing high rates of criminal violence or aiding the families of homicide victims. Radelet and

Borg agree that when the state puts vast resources into homicide cases that involve the death

penalty, non-homicidal cases are left with less resources for assisting the families of all homicide

victims (Radelet & Borg 2000). However, proponents of capital punishment would argue that

the retributive benefits of capital punishment are worth the costs (Radelet 2000).

On the other hand, there are anti-death penalty advocates who feel retribution fosters a

―cycle of violence‖. Therefore, they would argue that executing is not the answer. Proponents of

the death penalty utilize the Brutalization Hypothesis which proposes that for people who have a

predisposition to violence, executions and the attention that they receive act as an advertisement

27

which gives evidence to the benefits of violent behavior. In other words, the use of the death

penalty as a punishment reduces people‘s respect for life and thus increases the incidence of

violent acts (King 1978).

A former New Hampshire state representative, Renny Cushing, whose father was

murdered asks, ―How does killing someone demonstrate that killing is wrong?‖ He feels the

death penalty ―prompts us to revisit murder, re-victimize families, and create another family that

grieves.‖ He is one example of many cases in which families of murder victims do not support

capital punishment. In fact, there is a group that originated over twenty years ago, Murder

Victims Families for Reconciliation which has over 4,000 members. Some of these members

feel their loved ones deserve a more honorable memorial than what they refer to as a pre-

meditated, ―state-sanctioned‖ killing. They are among those who do not want the killers to be

killed because they do not feel that an execution will help them heal or contribute to reducing

homicide in the United States. Many in this group see the death penalty as a ―quick fix‖ that

doesn‘t change a society that breeds violence (Lampman 2001).

Author Michael Cohen, a retired professor at Murray State University, whose father was

shot to death when he was young, shares his argument and position against death penalty in a

2006 article. ―I oppose the death penalty not because it is morally wrong but because it is

ineffective and dangerous. Furthermore, it doesn‘t deter criminal behavior, it‘s more expensive

than life imprisonment, it‘s unsure, and it‘s sold politically and implemented widely in ways that

pander to racial bigotry‖ he says (Cohen 2006:20). In an article published by the Humanist, he

explains how ―Taking the heat of revenge out of the sentencing process means that sentences will

be fairer across lines of gender, race, and class because bias is more likely to sneak into the

process the more passionately it is conducted. Therefore, we need to restore to our courts the

28

social objectivity the Greeks attained, after so many generations of murder and revenge‖ (Cohen

2006:23).

Radelet and Borg state in their 2000 article that death penalty arguments are now less

focused on issues such as deterrence, cost and religious principles and more focused on

retribution. They believe that recent proponents of the death penalty are more aware of things

like racial and class bias, and are more aware of the inevitability of executing the innocent.

They argue that social science research is the reason the death penalty debate is changing and

there is a trend now toward the abolition of capital punishment (Radelet and Borg 2000).

According to Radelet and Borg, people nowadays are admitting that as long as we use the

death penalty, innocent defendants will occasionally be executed. Innocence is suddenly a

concern (Radelet and Borg 2000). In 1992, Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld at the Benjamin N.

Cardozo School of Law at Yeshiva University founded The Innocence Project to assist prisoners

who could be proved innocent through DNA testing. They claim their use of DNA technology

has provided proof that ―wrongful convictions are not isolated or rare events but instead arise

from systemic defects. Some of the causes they cite for wrongful death by capital punishment

include: eyewitness identification, unreliable/limited science, false confessions, forensic science

misconduct, government misconduct, and bad lawyering (www.innocenceproject.org January 14

2008).

As society notices more and more convicted felons later being released and considered

innocent, the question has become not will innocent people get put to death, but how many and is

it worth the benefits? ―Today the argument is not over the existence or even the inevitability of

such errors, but whether the alleged benefits of the death penalty outweigh these uncontested

liabilities‖ (Radelet 50: 2000). Several studies conducted over the last two decades have

29

documented the problem of erroneous convictions in homicide cases (Givelber 1997, Gross

1996, Huff et al 1996, Leo & Ofshe 1998, Radelet et al 1992). A recent nationwide poll found

that 58 percent of Americans are disturbed by the fact that the death penalty might result in the

execution of someone who is actually innocent (Ross 1996). Perhaps these cases that involve

innocent men sentenced to death are not as rare as the general public imagines. Regardless, it is

inevitable that innocent people will continue to be executed. Recently, there have been a large

number of people who were sentenced to death and later released from death row after proving

their innocence (Ross 1996). In 2008, the Death Penalty Information Center reported that since

1973, 123 people in 25 states have been released from death row with evidence of their

innocence. With errors such as this, some individuals are now finding themselves advocating on

the other side of the debate from where they once stood; even political figures. Supreme Court

Justice Harry Blackmun considered himself a supporter of the death penalty until 1994 when he

wrote that now he feels ―morally and intellectually obligated to concede that the death penalty

experiment has failed (Callins v. Collins, 510 U.S. 1141, 1145 (Fein 1994)).

Group Perceptions toward Capital Punishment

Many studies have determined that support for the death penalty varies based on personal

and demographic characteristics. Factors such as race, gender and religiosity have been

correlated to an individual‘s attitude toward capital punishment. As with other political debates,

arguments made between different groups of people have fluctuated depending on time in

history.

Race and Attitudes toward Capital Punishment

Many academics have begun to examine how public support for the death penalty is

related to racial conflict. Unnever and Cullen find in their 2007 study that capital punishment

30

and race in the United States are quite intertwined. Many have questioned whether African

Americans are more likely than whites to be sentenced to death. When comparable crimes are

researched, most research shows that the death penalty is three or four times more likely to be

imposed in cases in which the victim is white rather than black (Baldus & Woodworth 1998,

Baldus et al, 1990, Bowers et al 1984, Gross & Mauro 1989, Radelet & Pierce 1991).

The 2002 General Social Survey (Davis, Smith and Marsden 2002 ) reports that 73

percent of whites and 44 percent of African Americans support the death penalty for convicted

murders at that time. Research has had minimal explanation for why this gap exists. However,

the perception that more blacks are put to death than whites is likely the reason for the racial

difference in attitudes. The significant difference between the number of whites put to death

compared to blacks holds even when controls are introduced for correlates of death penalty

attitudes, such as political views, religion, class, gender as well as other variables (Unnever and

Cullen 2007).

Unnever and Cullen suggest that one source of this divide is white racism. They argue

that there is no theory of why white racism fosters support for capital punishment, but suggest

that there are factors that may have something to do with the linkage. These factors include

racial threat, racial stereotypes and racial resentment (Unnever and Cullen 2007). The idea of

racial threat is whites using the criminal justice system to subordinate minority groups. Through

this practice, whites can conceivably construct an ideology that justifies this injustice. In other

words, prejudiced whites might see the death penalty as a way to permit the criminal justice

system to suppress unwanted behavior of minorities. Second, prejudiced whites are likely to

hold stereotypes that lead them to assume that the most violent criminals are African American.

Therefore, these racist whites may believe legal penalties are applied mostly to African

31

Americans (Unnever and Cullen 2007). Third, white racists may think that African Americans

are criminally dangerous, even with special advantages that are not available to whites. They

may develop racial resentment, or an angry feeling that black crime is the fault of African

Americans themselves rather than a problem of society (Unnever and Cullen 2).

Michael Tonry argues that there is not as much political attention paid to the racial

disparities in the execution of death sentences ―despite longstanding evidence that a combination

of the offender‘s (black) and victim‘s (white) races is a primary determinant of capital

sentencing‖ (Tonry 2007:362). He explains that the black fraction of American prison

populations has increased from forty percent in the 1970s when the determinate sentencing

movement took place to around fifty percent by the late 1980s and has fluctuated until the time of

his research in 2005 ( Tonry 2007). Young (1992) suggested that African American

fundamentalists are less supportive of the death penalty because they attribute the case of crime

to situational characteristics. This, he argues, diminishes their desire to fully punish criminals

(Unnever, Cullen and Applegate 2005).

Gender and Attitudes toward Capital Punishment

Research on how gender relates to death penalty attitudes is harder to come by than some

other demographics. However, it is known that women have historically not been subject to the

death penalty at the same rates as men. In fact, from the first woman to have been recorded as

hanged in 1632 to the present, women have constituted 3% of executions in the United States.

(Deathpenalty.org/). A study in 1992 found women executed in the course of human history

were most likely to be black, executed for murder, older, to have been slaves, to have been in a

professional occupation, servants, or housewives. Men were more likely to be executed than

32

women in more recent periods, to be younger, and executed for a broader array of crimes (Harries

1992).

Religion and Attitudes toward Capital Punishment

Religious faith is widespread in the United States and has a notorious role in shaping

policy debates, capital punishment being one of those (Unnever, Cullen and Applegate 2005).

The leaders of Catholic, most Protestant and Jewish denominations are strongly opposed to the

death penalty (Radelet & Borg 2000). ―No longer are Old Testament religious arguments in

favor of the death penalty widely used or heard. Since the late 1990s the Catholic Church and its

leader, Pope John Paul II, are increasingly speaking out against the death penalty‖. (Radelet &

Borg 2000: 54). With Pope John Paul II‘s contemporary appeal to end the death penalty, many

religious organizations around the nation have issued statements opposing the death penalty.

Religious leader Reverend Bernice King, daughter of Martin Luther King Jr., shared her thoughts

publicly that ―Having lost my father and grandmother to gun violence, I will understand the deep

hurt and anger felt by the loved ones of those who have been murdered. Yet I can‘t accept the

judgment that their killers deserve to be executed. This merely perpetuates the tragic, unending

cycle of violence that destroys our hope for a decent society.‖

In the 1970s, the National Association of Evangelicals and the Moral Majority were

among the Christian groups who supported the death penalty. The NAE represented over 10

million conservative Christians and 47 denominations. More recently, the Fundamentalist and

Pentecostal churches have shown support for the death penalty, referencing biblical citings such

as the Old Testament (Bedau 1997). In addition, the Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints feel the

decision should be solely in the hands of the process of civil law. They do not strictly promote or

oppose the death penalty.

33

Although it was traditionally a supporter of the death penalty, the Roman Catholic

Church now generally opposes the death penalty. Most Protestant denominations such as

Baptists, Episcopalians, Lutherans, Methodists, Presbyterians, and the United Church of Christ

are also in opposition. Since the 1960s when religious activists worked to abolish the death

penalty, many continue to do so today (deathpenaltyinfo.org/).

It is conceivable that age and education also have a relationship with attitudes toward the

death penalty, just as they are associated with attitudes toward abortion. However, research on

this is scarce.

Collective Views toward Abortion and Capital Punishment

Needless to say, it is quite evident by the extensive history of abortion and capital

punishment arguments that our country will probably continue to debate these topics for years to

come. Public opinion has continued to play a vital role in both abortion and capital punishment

policies in the United States (Langer & Brace 2005).

As Darwin Sawyer points out, although it is typically assumed that someone either favors

or opposes the right to end human life, regardless of the circumstances surrounding the action,

this is not generally the case. In other words, people are often thought of as being consistent in

their views toward life-taking issues and as not letting other considerations cloud their life

orientations (Sawyer 1982). This idea closely ties into capital punishment and abortion because

both can be considered life-taking actions. It is well worth noting that many people who claim to

value life above all are highly in favor of capital punishment; by some abortion and capital

punishment are equally considered as life-taking actions.

34

Attitudes toward abortion and capital punishment can both be visualized as lying on a

continuum. At one end of the abortion debate, there are the people who condemn abortion under

any circumstance and actually equate it with murder, known to most as pro-lifers. On the

opposite end is the pro-choice group who oppose any legal restrictions on abortion. Most of the

general public actually lies somewhere in between, and have been characterized as ―ambivalent‖

because people‘s beliefs are not consistently pro-choice or pro-life. Where people fall probably

reflects their interests, beliefs, and values (Strickler and Danigelis 2002) as well as their

structural and social location.

Another way to understand the relation in attitudes toward abortion and capital

punishment is by breaking the attitudes down into four simple categories as was demonstrated in

Figure 1. For the use of this study, the first category consists of those who approve of abortion

and are not against the use of capital punishment. This will be called the ―Anti-Life‖ category.

People who approve of abortion but oppose capital punishment make up the second group,

known as the ―Liberal‖ group. Members of the third group, the ―Conservatives‖ are those who

are against abortion while in favor of the death penalty. Finally, ―Pro-Lifers‖ consist of people

that are against both abortion and capital punishment.

It is clear that there are inconsistencies within this framework. While the ―Pro-Life‖

individuals value life in all cases, the ―Conservative‖ group members feel that life worth saving

in the case of abortion, but not in capital punishment. They believe in the sanctity of human life

in one case, but not in the other. The ―Liberal‖ group values life in the case of capital

punishment but approve of abortion. Again, this is a group that believes in the sanctity of human

life in one case, but not in the other. Finally, those in the ―Anti-Life‖ value life in neither case.

35

The Conservatives can be considered the extreme ―for-life‖ group, as the Anti-Life group

can be considered the extreme ―for-death‖ group. As Darwin Sawyer found, individuals display

a definite strain toward consistency in their attitudes toward life-taking and life-supporting

actions. The fact that someone opposes the death penalty does not imply opposition to legal

abortion as well, although, he says, it does suggest greater tendencies in that direction (Sawyer

1982).

Figure 1 could conceivably illustrate the difference between political congruence and

issue congruence. An individual who is pro-life in the case of abortion and at the same time, an

advocate of the death penalty would be considered ―politically congruent‖. On the other hand, an

individual who is pro-life in the case of abortion and at the same time does not support the death

penalty could be considered ―issue congruent‖ in regards to the topic of life-taking actions. The

idea that people can hold opposing views toward life and death issues raises the question of

whether these attitudes are a reflection of just individual characteristics, or whether external

forces sway opinions as well.

36

Based on the literature I have mentioned, I expect to see the following results:

1. African Americans will be more supportive of abortion yet less supportive of capital

punishment than whites. They will be more likely to fall into the Liberal category and less

likely to fall into the Conservative category on Figure 1.

2. Men will be more supportive of abortion and more likely to approve of capital

punishment than women. They will be more likely to fall into the Anti-Life category on

Figure 1 than women.

3. Individuals with less religiosity will be more supportive of abortion and less supportive of

capital punishment than those with higher religiosity. They will be more likely to fall into

the Liberal category on Figure 1 than individuals with higher religiosity.

4. Individuals with a higher educational attainment will be more likely to approve of

abortion and less likely to approve of capital punishment than individuals with less

educational attainment. They are more likely to fall into the Liberal category on Figure 1

than those with less educational attainment.

5. Older people will be less likely than younger people to approve of abortion rights.

37

Theory of Spatial Clustering and Cognitive Bundling

While there seem to be many contributing factors that influence attitudes toward abortion

and capital punishment, researchers have speculated that these factors are not only individually

formed within our own minds, but rather we are strongly influenced by the world around us.

Lavine and Latane suggest the internal structure of people‘s attitudes may reflect the external

structure of information in the social environment. They describe the way in which people

internally organize their attitudes and attempt to maximize the internal consistency of these

attitudes (Lavine and Latane 1996). They say public opinion is the result of processes occurring

within the minds of individuals as a result of social interaction and communication. However,

they find that at the same time this internal organizing is happening, the dynamics of public

opinion are also determined by processes resulting from interpersonal influence. So, events in

the external world lead to modifications of relations between attitudes in the minds of individuals

through repeated patters. They are ―updated over time to provide an adequate internal

representation of what is perceived to exist in the internal environment‖ (Lavine and Latane

1996: 54). So, as a result of spatial clustering, if capital punishment advocates also tend to be

opponents of legalized abortion, individuals may come to believe that support for one implies

opposition to the other. Thus, as the structure of public opinion changes at the societal level, this

may cause attitudes to become ―bundled‖ together in the minds of individuals (Lavine and Latane

1996). Individuals can then become likely to recognize the themes through which a given bundle

of attitudes is related.

The ―culture of life‖ argument mentioned previously is not comprised of consistent views

toward life and death decisions such as abortion and capital punishment. The conservative

position seems to support the anti-life capital punishment position and simultaneously disagree

38