A5_SEAMAN (DO NOT DELETE) 7/4/2016 4:32 PM

1949

Permanent Injunctions in Patent

Litigation After eBay: An Empirical Study

Christopher B. Seaman

*

ABSTRACT: The Supreme Court’s 2006 decision in eBay v.

MercExchange is widely regarded as one of the most important patent law

rulings of the past decade. Historically, patent holders who won on the merits

in litigation nearly always obtained a permanent injunction against

infringers. In eBay, the Court unanimously rejected the “general rule” that a

prevailing patentee is entitled to an injunction, instead holding that lower

courts must apply a four-factor test before granting such relief. Ten years later,

however, significant questions remain regarding how this four-factor test is

being applied, as there has been little rigorous empirical examination of

eBay’s actual impact in patent litigation.

This Article helps fill this gap in the literature by reporting the results of an

original empirical study of contested permanent injunction decisions in

district courts for a 7.5-year period following eBay. It finds that eBay has

effectively created a bifurcated regime for patent remedies, as operating

companies who compete against an infringer still obtain permanent

injunctions in the vast majority of cases that are successfully litigated to

judgment. In contrast, non-competitors and other non-practicing entities are

generally denied injunctive relief. These findings are robust even after

controlling for the field of patented technology and the particular court that

decided the injunction request. This Article also finds that permanent

injunction rates vary significantly based on patented technology and forum.

Finally, this Article considers some implications of these findings for both

participants in the patent system and policy makers.

*

Associate Professor of Law, Washington and Lee University School of Law. I thank Eric

Claeys, Ryan Holte, Doug Rendleman, Karen Sandrik, Dave Schwartz, and participants of the First

Annual Workshop on Empirical Methods in Intellectual Property at IIT Chicago-Kent College of

Law, the 2015 Works in Progress in Intellectual Property Colloquium at the United States Patent

and Trademark Office, and the Fifth Annual Patent Conference at the University of Kansas

School of Law for their valuable feedback on this project. I also thank Sarah Kathryn Atkinson,

Ross Blau, Will Hoing, Sharon Jeong, and Richard Zhang for their excellent research assistance

on this project. The financial support of the Frances Lewis Law Center at Washington and Lee

University School of Law is gratefully acknowledged. Comments welcome at [email protected].

A5_SEAMAN (DO NOT DELETE) 7/4/2016 4:32 PM

1950 IOWA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 101:1949

I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 1950

II. PROPERTY RULES, LIABILITY RULES, AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY:

AN OVERVIEW ............................................................................. 1954

III. PATENTS AND THE RIGHT TO EXCLUDE ...................................... 1959

A. HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT ................................................... 1959

1. Initial District Court Decision .................................... 1962

2. Federal Circuit Decision ............................................. 1963

3. Supreme Court Decision ............................................ 1964

4. After Remand .............................................................. 1967

B. EXISTING LITERATURE ON EBAY’S IMPACT ............................. 1968

IV. METHODOLOGY .......................................................................... 1974

A. RESEARCH QUESTIONS ........................................................... 1974

B. STUDY DESIGN AND DATA COLLECTION .................................. 1975

C. LIMITATIONS ........................................................................ 1979

V. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION .......................................................... 1982

A. DECISIONS DATASET .............................................................. 1982

1. Overall Grant Rate ...................................................... 1982

2. Grant Rate by Patented Technology .......................... 1984

3. Grant Rate by District .................................................. 1985

4. Grant Rate by PAE Status ............................................ 1987

5. Grant Rate and Competition Between Litigants ....... 1990

6. Irreparable Harm Findings ........................................ 1992

7. Other eBay Factors ....................................................... 1994

8. Regression Analysis ..................................................... 1995

B. PATENTS DATASET ................................................................ 2000

C. IMPLICATIONS ....................................................................... 2002

VI. CONCLUSION .............................................................................. 2006

APPENDIX A: LIST OF INJUNCTION DECISIONS ....................................... 2007

I. I

NTRODUCTION

The Supreme Court’s 2006 opinion in eBay v. MercExchange, which held

that prevailing patentees in litigation are not automatically entitled to a

permanent injunction,

1

is widely regarded as one of the most significant

1. See eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C., 547 U.S. 388, 393–94 (2006) (holding that the

Federal Circuit erred in “articulat[ing] a general rule, unique to patent disputes, that a

permanent injunction will issue once infringement and validity have been adjudged”).

A5_SEAMAN (DO NOT DELETE) 7/4/2016 4:32 PM

2016] PERMANENT INJUNCTIONS IN PATENT LITIGATION 1951

patent law decisions of the past decade.

2

It has been extensively cited by lower

federal courts,

3

and is the subject of numerous law review articles.

4

The case

has also spawned a significant transformation in the field of remedies,

reshaping the test for permanent injunctive relief in numerous areas outside

of patent law.

5

Despite its perceived importance, however, there has been little rigorous

empirical examination of eBay’s actual impact in patent litigation.

6

This is

significant because the eBay decision—which was unanimous—contains two

2. See Colleen V. Chien & Mark A. Lemley, Patent Holdup, the ITC, and the Public Interest, 98

C

ORNELL L. REV. 1, 8 (2012) (“The Supreme Court’s 2006 decision in eBay represented a sea change

in patent litigation.” (footnote omitted)); Ryan Davis, Top 15 High Court Patent Rulings of the Past 15

Years, L

AW360 (July 1, 2015, 8:27 PM), http://www.law360.com/articles/674205/top-15-high-court-

patent-rulings-of-the-past-15-years (ranking eBay as the second most important patent law decision since

2000).

3. A recent search of WestlawNext finds that eBay has been cited in over 2000 federal court

opinions. See Citing References for eBay Inc. v. MercExchange L.L.C., W

ESTLAWNEXT (last visited May 10,

2016); see also Dennis Crouch, Most Cited Supreme Court Patent Decisions (2005–2015), P

ATENTLY-O (Mar.

11, 2015), http://patentlyo.com/patent/2015/03/supreme-court-cases.html (listing eBay as the

second most cited U.S. Supreme Court patent case of the past decade).

4. For examples of significant eBay-related scholarship, see generally Andrew Beckerman-

Rodau, The Aftermath of eBay v. MercExchange, 126 S. Ct. 1837 (2006): A Review of Subsequent

Judicial Decisions, 89

J. PAT. & TRADEMARK OFF. SOC’Y 631 (2007); Michael W. Carroll, Patent

Injunctions and the Problem of Uniformity Cost, 13 M

ICH. TELECOMM. & TECH. L. REV. 421 (2007);

Bernard H. Chao, After eBay, Inc. v. MercExchange: The Changing Landscape for Patent Remedies, 9

M

INN. J.L. SCI. & TECH. 543 (2008); Chien & Lemley, supra note 2; Eric R. Claeys, The Conceptual

Relation Between IP Rights and Infringement Remedies, 22 G

EO. MASON L. REV. 825 (2015); Vincenzo

Denicolò et al., Revisiting Injunctive Relief: Interpreting eBay in High-Tech Industries with Non-

Practicing Patent Holders, 4 J.

COMPETITION L. & ECON. 571 (2008); Douglas Ellis et al., The

Economic Implications (and Uncertainties) of Obtaining Permanent Injunctive Relief After eBay v.

MercExchange, 17 F

ED. CIR. B.J. 437 (2008); Mark P. Gergen, John M. Golden & Henry E. Smith,

The Supreme Court’s Accidental Revolution? The Test for Permanent Injunctions, 112 C

OLUM. L. REV.

203 (2012); John M. Golden, “Patent Trolls” and Patent Remedies, 85 T

EX. L. REV. 2111 (2007)

[hereinafter Golden, Patent Trolls]; John M. Golden, Principles for Patent Remedies, 88 T

EX. L. REV.

505 (2010) [hereinafter Golden, Principles]; Ryan T. Holte, The Misinterpretation of eBay v.

MercExchange and Why: An Analysis of the Case History, Precedent, and Parties, 18 C

HAP. L. REV. 677

(2015) [hereinafter Holte, Misinterpretation of eBay]; Ryan T. Holte, Trolls or Great Inventors: Case

Studies of Patent Assertion Entities, 59 S

T. LOUIS U. L.J. 1 (2014) [hereinafter Holte, Trolls or Great

Inventors]; Sarah R. Wasserman Rajec, Tailoring Remedies to Spur Innovation, 61 A

M. U. L. REV. 733

(2012); Doug Rendleman, The Trial Judge’s Equitable Discretion Following eBay v. MercExchange,

27 R

EV. LITIG. 63 (2007); and Karen E. Sandrik, Reframing Patent Remedies, 67 U. MIAMI L. REV.

95 (2012).

5. See Gergen et al., supra note 4, at 205 (“[T]he four-factor test from eBay has, in many

federal courts, become the test for whether a permanent injunction should issue, regardless of

whether the dispute in question centers on patent law, another form of intellectual property,

more conventional government regulation, constitutional law, or state tort or contract law.”); see

also Shyamkrishna Balganesh, Demystifying the Right to Exclude: Of Property, Inviolability, and

Automatic Injunctions, 31 H

ARV. J.L. & PUB. POL’Y 593, 598–99 (2008) (discussing eBay’s impact

in real and personal property law); Jiarui Liu, Copyright Injunctions After eBay: An Empirical Study,

16 L

EWIS & CLARK L. REV. 215, 218 (2012) (examining “how much the eBay decision has guided,

and should guide, copyright cases”).

6. See infra Part III.C (discussing the existing empirical work on this subject).

A5_SEAMAN (DO NOT DELETE) 7/4/2016 4:32 PM

1952 IOWA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 101:1949

concurring opinions that express seemingly divergent perspectives regarding

the availability of permanent injunctions in future patent cases.

7

In particular,

it remains hotly contested whether so-called patent assertion entities

(“PAEs”)

8

—firms who principally exploit their patents through litigation

and/or licensing rather than directly practicing them and who are sometimes

pejoratively referred to as “patent trolls”

9

—should be able to obtain injunctive

relief.

10

This Article helps fill this significant gap in the literature by reporting the

results of an original empirical study of contested permanent injunction

decisions in the federal district courts for a 7.5 year period following eBay,

representing the most in-depth effort to date to assess the post-eBay landscape.

The data in this study reveal that, while the vast majority of patentees still

obtain injunctive relief following eBay, PAEs rarely do.

11

This finding remains

robust even after controlling for the field of technology of the infringed

patents and the district court that decided the case.

12

Furthermore, PAEs

7. See infra Part III.B.3.

8. See F

ED. TRADE COMM’N, THE EVOLVING IP MARKETPLACE: ALIGNING PATENT NOTICE

AND

REMEDIES WITH COMPETITION 220 n.21 (2011) (“This report uses the term ‘patent assertion

entity’ [or PAE] . . . to refer to firms whose business model focuses on purchasing and asserting

patents.”); Colleen V. Chien, From Arms Race to Marketplace: The Complex Patent Ecosystem and Its

Implications for the Patent System, 62

HASTINGS L.J. 297, 328 (2010) (explaining that PAEs “are

focused on the enforcement, rather than the active development or commercialization of their

patents,” and noting that PAEs “can be further divided into several types—large-portfolio

companies, small-portfolio companies, and individuals”); see also James Bessen & Michael J.

Meurer, The Direct Costs from NPE Disputes, 99 C

ORNELL L. REV. 387, 390 (2014) (defining a related

concept, non-practicing entities (“NPEs”), as “individuals and firms who own patents but do not

directly use their patented technology to produce goods or services, instead asserting their

patents against companies that do produce goods and services”).

9. See In re Packard, 751 F.3d 1307, 1325 (Fed. Cir. 2014) (Plager, J., concurring) (“Patent

trolls are also known by a variety of other names: ‘patent assertion entities’ (PAEs), [and] ‘non-

practicing entities’ (NPEs).”). For an informative history of the term “patent troll” and its

malleability, see Kristen Osenga, Formerly Manufacturing Entities: Piercing the “Patent Troll” Rhetoric,

47 C

ONN. L. REV. 435, 442–45 (2014). See also Edward Lee, Patent Trolls: Moral Panics, Motions in

Limine, and Patent Reform, 19 S

TAN. TECH. L. REV. 113, 117 (2015) (conducting “the first empirical

study of the use of the term ‘patent troll’ by U.S. media” and finding that “starting in 2006, the

U.S. media surveyed used ‘patent troll’ far more than any other term, despite the efforts of

scholars to devise alternative, more neutral-sounding terms”).

10. Compare F

ED. TRADE COMM’N, supra note 8, at 229 (explaining that when a PAE “seeks

to license broadly, denial of an injunction” may be appropriate), and Mark A. Lemley & Carl

Shapiro, Patent Holdup and Royalty Stacking, 85 T

EX. L. REV. 1991, 2035–36 (2007) (contending

that a “presumptive right to injunctive relief” should apply for patent holders who compete or

exclusively license to a party that does, with other patentees being subject to a less favorable rule),

with Golden, Patent Trolls, supra note 4, at 2148 (contending that “a categorically discriminatory

rule” against non-practicing patentees “is not needed”), and Richard A. Epstein, The Property Rights

Movement and Intellectual Property, R

EG. 58, 62 (2008) (criticizing eBay as creating a risk of

“systematic under-compensation during the limited life of a patent[, which] is likely to reduce

the level of innovation while increasing the administrative costs of running the entire system”).

11. See infra Part V.A.4.

12. See infra Part V.A.8.

A5_SEAMAN (DO NOT DELETE) 7/4/2016 4:32 PM

2016] PERMANENT INJUNCTIONS IN PATENT LITIGATION 1953

often cannot establish the type of injury deemed “irreparable” following eBay,

which is a prerequisite to obtaining a permanent injunction.

13

In sum, district

courts appear to have adopted a de facto rule against injunctive relief for PAEs

and other patent owners who do not directly compete in a product market

against an infringer—a rule which, ironically, is in tension with the Supreme

Court’s conclusion in eBay that “the District Court erred in its categorical

denial of injunctive relief” to a non-practicing patentee.

14

This Article also evaluates the impact of other considerations on

permanent injunction decisions after eBay. It finds that grant rates vary

significantly by field of technology, with injunctions nearly always granted in

cases involving patented drugs and biotechnology, but much less often for

disputes involving computer software.

15

The study also finds that grant rates

differ by district, even after controlling for the propensity of PAE litigants to

file lawsuits in particular courts.

16

Furthermore, it assesses whether several

other factors mentioned in the concurring opinions in eBay and the district

court’s decision after remand—such as the patentee’s willingness to license

the patented technology, whether the patented technology covers only a small

component of an infringing product, and a finding that the defendant

willfully infringed the patent—are correlated with injunction decisions.

17

Finally, this Article reports the results of a second, related dataset that

explores whether traditionally accepted indicators of patent value are

correlated with injunction decisions.

18

Somewhat surprisingly, it finds that

these indicators are not predictive of whether a patentee is likely to receive an

injunction.

19

The balance of this Article is organized as follows. Part II provides an

overview of the theoretical distinction between property rules and liability

rules for enforcing legal rights, focusing on their application to intellectual

property (“IP”) rights. Part III traces the historical development of the right

to exclude in patent law. It then analyzes the eBay litigation and concludes

with an overview of the existing literature on eBay’s impact in patent litigation.

Part IV describes the research questions considered in this empirical study

and the methodology used to address them. Part V reports the study’s findings

and assesses their implications for patentees, users of patented technology,

13. See infra Part V.A.6.

14. eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C., 547 U.S. 388, 394 (2006); see also MercExchange

L.L.C. v. eBay, Inc. (MercExchange I), 275 F. Supp. 2d 695, 712 (E.D. Va. 2003) (“In the case at

bar, the evidence of the plaintiff’s willingness to license its patents, its lack of commercial activity

in practicing the patents, and its comments to the media as to its intent with respect to

enforcement of its patent rights, are sufficient to rebut the presumption that it will suffer

irreparable harm if an injunction does not issue.”).

15. See infra Part V.A.2.

16. See infra Parts V.A.3, V.A.8.

17. See infra Part V.A.8.

18. See infra notes 202, 316–19 and accompanying text.

19. See infra Part V.B.

A5_SEAMAN (DO NOT DELETE) 7/4/2016 4:32 PM

1954 IOWA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 101:1949

and the patent system and innovation policy more generally. In particular, it

considers the impact of widespread denial of injunctive relief on non-

practicing patentees. Part VI concludes.

II. P

ROPERTY RULES, LIABILITY RULES, AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY:

A

N OVERVIEW

In their landmark article, Property Rules, Liability Rules, and Inalienability:

One View of the Cathedral, now-Judge Guido Calabresi and A. Douglas Melamed

developed an analytic framework for protecting “entitlements”—the right to

do something, or the right to prevent others from doing something.

20

An

entitlement is not self-executing. Rather, the legal system must establish some

mechanism to enforce entitlements.

21

Calabresi and Melamed distinguished

between two primary forms

22

of protection for an entitlement: property rules

and liability rules.

23

Under a property rule, an entitlement can only be taken or transferred

with a property owner’s consent.

24

As explained by Calabresi and Melamed,

20. See Guido Calabresi & A. Douglas Melamed, Property Rules, Liability Rules, and

Inalienability: One View of the Cathedral, 85 H

ARV. L. REV. 1089, 1090 (1972) (“The first issue which

must be faced by any legal system is one we call the problem of ‘entitlement.’ Whenever a state is

presented with the conflicting interests of two or more people . . . it must decide which side to

favor. . . . Hence the fundamental thing that law does is to decide which of the conflicting parties

will be entitled to prevail.”); see also Madeline Morris, The Structure of Entitlements, 78 C

ORNELL L.

REV. 822, 827–39 (1993) (describing in more detail the allocation and construction of legal

entitlements).

21. See Calabresi & Melamed, supra note 20, at 1090 (“Having made its . . . choice, society

must enforce that choice. Simply setting the entitlement does not avoid the problem of ‘might

makes right’; a minimum of state intervention is always necessary.”).

22. A third form of protection for entitlements, inalienable entitlements, exists when the

transfer of that entitlement “is not permitted between a willing buyer and a willing seller.” Id. at

1092. For purposes of this Article, inalienable entitlements are not at issue, as patent rights are

freely transferable to others through assignment and licensing. See 35 U.S.C. § 261 (2012)

(noting that patents and patent applications “shall be assignable in law by an instrument in

writing”); Isr. Bio-Eng’g Project v. Amgen, Inc., 475 F.3d 1256, 1264 (Fed. Cir. 2007) (“Under

long established law, a patentee or his assignee may grant and convey to another: (1) the whole

patent, (2) an undivided part or share of that exclusive right, or (3) the exclusive right under the

patent within and throughout a specified part of the United States.”).

23. Calabresi & Melamed, supra note 20, at 1092. Calabresi and Melamed correctly note

that “[t]he[se] categories are not . . . absolutely distinct.” Id. For instance, if monetary damages—

which usually embody a liability rule—are sufficiently high, they can operate more like a property

rule because potential takers of an entitlement would be deterred from doing so. See Ian Ayres &

Eric Talley, Solomonic Bargaining: Dividing a Legal Entitlement to Facilitate Coasean Trade, 104 Y

ALE

L.J. 1027, 1040–41 (1995) (explaining that with “relatively high damages, potential takers would

be deterred from nonconsensual takings, and the entitlement would be transferred only by

consensual agreement”). Some scholars have criticized the distinction between property rules

and liability rules as having little relationship to the normative judgments embedded in private

law remedies determinations. See Claeys, supra note 4, at 839–40 (contending that “‘Cathedral’-

style analysis raises normative questions more vexing than is often appreciated,” including

measures of efficiency and initial allocation of resource entitlements to parties).

24. See Calabresi & Melamed, supra note 20, at 1105 (“In our framework, much of what is

A5_SEAMAN (DO NOT DELETE) 7/4/2016 4:32 PM

2016] PERMANENT INJUNCTIONS IN PATENT LITIGATION 1955

“[a]n entitlement is protected by a property rule to the extent that someone

who wishes to remove the entitlement from its holder must buy it from him

in a voluntary transaction in which the value of the entitlement is agreed upon

by the seller.”

25

For instance, a property rule would require the user of an IP

right to obtain prior permission from its owner, which the owner would be

free to withhold.

26

Thus, the holder of an entitlement protected by a property

rule has the exclusive power to determine its value ex ante.

27

Injunctive relief

is the dominant means for enforcing a property rule.

28

In contrast, a liability rule exists when another party may violate an

entitlement “if [it] is willing to pay an objectively determined value for it.”

29

Thus, under a liability-rule regime, entitlements are protected, “but their

transfer or destruction is allowed on the basis of a value determined by some

[third-party authority] rather than by the parties themselves.”

30

For instance,

a liability rule applies when an IP right may be infringed in exchange for a

predetermined royalty rate, as is the case for several compulsory licensing

generally called private property can be viewed as an entitlement which is protected by a property

rule. No one can take the entitlement . . . unless the holder sells it willingly and at the price at

which he subjectively values the property.”).

25. Id. at 1092.

26. See Robert P. Merges, Of Property Rules, Coase, and Intellectual Property, 94 C

OLUM. L. REV.

2655, 2655 (1994) (“[A] property rule is a legal entitlement that can only be infringed after

bargaining with the entitlement holder.”).

27. See Calabresi & Melamed, supra note 20, at 1092 (explaining that a property rule “lets

each of the parties say how much the entitlement is worth . . . and gives the seller a veto if the

buyer does not offer enough”); see also Richard A. Epstein, A Clear View of The Cathedral: The

Dominance of Property Rules, 106 Y

ALE L.J. 2091, 2091 (1997) (“Because property rules give one

person the sole and absolute power over the use and disposition of a given thing, it follows that

its owner may hold out for as much as he pleases before selling the thing in question . . . .”).

28. See Merges, supra note 26, at 2655 (calling injunctions “the classic instance of a property

rule”); Henry E. Smith, Property and Property Rules, 79 N.Y.U.

L. REV. 1719, 1720 (2004) (“Such

‘property rules’ would include injunctions . . . .”). As my colleague Professor Doug Rendleman

has explained, however, an enjoined party “can violate an injunction and convert the plaintiff’s

[property] right into a cause of action for compensatory contempt, money,” and monetary

remedies are more characteristic of a liability rule. D

OUG RENDLEMAN, COMPLEX LITIGATION:

INJUNCTIONS, STRUCTURAL REMEDIES, AND CONTEMPT 128 (2010); see also John M. Golden,

Injunctions as More (or Less) than “Off Switches”: Patent-Infringement Injunctions’ Scope, 90 T

EX. L. REV.

1399, 1412–13 (2012) (“When any threat of being found in contempt is realistically limited to a

threat of civil contempt . . . [the] risk of being found in contempt can essentially amount to no

more than a risk of being subjected to heightened but still limited monetary sanctions.”).

29. Calabresi & Melamed, supra note 20, at 1092.

30. Id. Eric Claeys has criticized the “liability rule” concept as failing to fully reflect “private

law judgments about wrongs and rights” and thus “eras[ing] some of the stigma associated with”

certain forms of tortious conduct. Claeys, supra note 4, at 845–46; see also Jules L. Coleman & Jody

Kraus, Rethinking the Theory of Legal Rights, 95 Y

ALE L.J. 1335, 1340 (1986) (asserting that because

“liability rules neither confer nor respect a domain of lawful control, liability rules cannot, in this

view, protect rights. . . . The very idea of a ‘liability rule entitlement,’ that is of a right secured by

a liability rule, is inconceivable”).

A5_SEAMAN (DO NOT DELETE) 7/4/2016 4:32 PM

1956 IOWA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 101:1949

provisions in the Copyright Act.

31

As a result, “a liability rule denies the holder

of the asset the power to exclude others.”

32

There is a sizable body of literature analyzing the normative question of

whether property rules or liability rules are preferable for the enforcement of

IP rights.

33

Traditionally, the property rule of injunctive relief “has dominated

the law of intellectual property.”

34

Several rationales have been offered in

support of “the strong presumption” of property rules for IP rights.

35

First,

unlike most other forms of property (e.g., real property), intellectual property

is non-rivalrous and non-excludable absent effective legal protection.

36

This

prevents owners of intellectual property from restricting access to “free riders”

who have not incurred the costs of creation from exploiting it.

37

The difficulty

31. See, e.g., 17 U.S.C. § 111 (2012) (compulsory licensing of secondary transmission of

television programming by cable systems); id. § 114(d)–(f) (compulsory licensing of certain

digital audio transmissions); id. § 115 (compulsory licensing of previously-released nondramatic

musical works); see also Daniel A. Crane, Intellectual Liability, 88 T

EX. L. REV. 253, 259–63 (2009)

(discussing in further detail compulsory licensing provisions in the Copyright Act); Joseph P. Liu,

Regulatory Copyright, 83 N.C.

L. REV. 87, 108–22 (2004) (detailing the compulsory licensing

provisions’ depth and scope).

32. Epstein, supra note 27, at 2091; see also Andrew W. Torrance & Bill Tomlinson, Property

Rules, Liability Rules, and Patents: One Experimental View of the Cathedral, 14 Y

ALE J.L. & TECH. 138,

144 (2011) (“Under a liability rule, the owner of an entitlement is legally powerless to keep it

exclusively for herself.”).

33. See Mark A. Lemley & Philip J. Weiser, Should Property or Liability Rules Govern

Information?, 85 T

EX. L. REV. 783, 784 (2007) (arguing that liability rules are preferable to

traditional property rights in markets where injunctive relief cannot be narrowly tailored);

Merges, supra note 26, at 2664–65 (arguing property rights are generally preferable in protecting

intellectual property); Henry E. Smith, Intellectual Property as Property: Delineating Entitlements in

Information, 116 Y

ALE L.J. 1742, 1799–1806 (2007) (explaining how information costs help

explain why copyright law relies more on liability rights and patent law relies more on property

rights); Stewart E. Sterk, Property Rules, Liability Rules, and Uncertainty About Property Rights, 106

M

ICH. L. REV. 1285, 1304–08 (2008) (arguing that liability rules limit incentives to conduct

searches for the scope of property rights); see also Crane, supra note 31, at 255 (reframing the

“property–liability debate” by focusing more broadly on other rights inherent in intellectual

property).

34. Ben Depoorter, Property Rules, Liability Rules and Patent Market Failure, 1 E

RASMUS L. REV.

59, 61 (2008); see also Balganesh, supra note 5, at 598 (“[T]he right to exclude in the context of

both tangible and intangible property has come to be associated with an entitlement to

exclusionary (injunctive) relief.”); Kenneth W. Dam, The Economic Underpinnings of Patent Law, 23

J.

LEGAL STUD. 247, 255 (1994) (“Remedies for infringement of a patent are, with limited

exceptions, those appropriate for property. Injunctions, both permanent and temporary, are

available against infringers on proof of validity and infringement.”).

35. Merges, supra note 26, at 2667.

36. Smith, supra note 33, at 1744; see also R

OBERT P. MERGES, PETER S. MENELL & MARK A.

LEMLEY, INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY IN THE NEW TECHNOLOGICAL AGE 2 (6th ed. 2012) (“All

justifications for intellectual property protection . . . must contend with a fundamental difference

between ideas and tangible property. Tangible property . . . is composed of atoms, physical things

that can occupy only one place at a given time. This means that possession of a physical thing is

necessarily ‘exclusive’ . . . . Ideas, though, do not have this characteristic of excludability.”).

37. See Michael A. Carrier, Cabining Intellectual Property Through a Property Paradigm, 54 D

UKE

L.J. 1, 32–33 (2004). For the leading critique of the idea that eliminating free riding is a primary

A5_SEAMAN (DO NOT DELETE) 7/4/2016 4:32 PM

2016] PERMANENT INJUNCTIONS IN PATENT LITIGATION 1957

of valuing IP rights is another rationale advanced for a property rule.

38

“Because each asset covered by an [IP right] is in some sense unique,” it can

be “difficult for a court . . . to properly value the [IP] right-holder’s loss.”

39

However, some scholars have argued in favor of imposing liability rules

on IP rights, at least in certain circumstances.

40

One situation where liability

rules may be preferred is when private ordering—for instance, ex ante

licensing under a property rule—would result in an inefficient outcome. This

might occur, for example, if high transaction costs prevent the parties from

reaching an otherwise mutually beneficial agreement regarding the use of IP

rights.

41

High transaction costs may exist if numerous parties are involved in

the bargaining process, such as when IP rights to various aspects of a particular

technology are owned by disparate entities.

42

These difficulties may be

compounded by the uncertain scope of some IP rights, such as the meaning

of a patent’s claims.

43

Holdup is another reason advanced by some scholars for adopting

liability rules.

44

Holdup occurs when an IP owner uses the prospect of

goal of intellectual property law, see Mark A. Lemley, Property, Intellectual Property, and Free Riding,

83 T

EX. L. REV. 1031, 1032 (2005).

38. See T

HOMAS F. COTTER, COMPARATIVE PATENT REMEDIES: A LEGAL AND ECONOMIC

ANALYSIS 54 (2013) (“[T]he job of putting a value on patent rights is inherently difficult,

particularly in industries in which the technology itself is rapidly evolving.”); Golden, Patent Trolls,

supra note 4, at 2152 (explaining “[t]he difficulty of assessing [damages] has in fact been one of

the principal rationales for granting permanent injunctions” in patent cases).

39. Merges, supra note 26, at 2664. One common approach for valuing IP is to compare

“the advantages it confers . . . with the next-best available alternative.” C

OTTER, supra note 38, at

53–54; see also Christopher B. Seaman, Reconsidering the Georgia-Pacific Standard for Reasonable

Royalty Patent Damages, 2010 BYU

L. REV. 1661, 1711–15 (2010) (discussing the role of non-

infringing alternatives in determining royalty rates for patent rights).

40. See Crane, supra note 31, at 254 (“Intellectual property is incrementally moving away

from . . . . a property regime to a liability regime.”).

41. See Ian Ayres & J.M. Balkin, Legal Entitlements as Auctions: Property Rules, Liability Rules,

and Beyond, 106 Y

ALE L.J. 703, 706 n.9 (1996) (“[L]egal scholars have interpreted Calabresi and

Melamed to be saying that property rules are more efficient when transaction costs are low.”);

Merges, supra note 26, at 2655 (“Ever since Calabresi and Melamed, transaction costs have

dominated the choice of the proper entitlement rule, with a liability rule being the entitlement

of choice when transaction costs are high.”). Collective rights organizations have emerged as one

mechanism to mitigate this problem. See generally Robert P. Merges, Contracting into Liability Rules:

Intellectual Property Rights and Collective Rights Organizations, 84 CALIF. L. REV. 1293 (1996).

42. See Lemley & Weiser, supra note 33, at 793 (noting “that if a buyer must aggregate rights

from a number of different parties in order to achieve a useful end result, it will have to deal with

a number of different sellers,” thus raising transaction costs).

43. See J

AMES BESSEN & MICHAEL J. MEURER, PATENT FAILURE: HOW JUDGES, BUREAUCRATS,

AND

LAWYERS PUT INNOVATORS AT RISK 46–72 (2008) (arguing that patents fail to provide clear

notice of the scope of patent rights); Greg Reilly, Completing the Picture of Uncertain Patent Scope, 91

W

ASH. U. L. REV. 1353, 1353 (2014) (“Uncertain patent scope is perhaps the most significant

problem facing the patent system.”); see also Festo Corp. v. Shoketsu Kinzoku Kogyo Kabushiki

Co., 535 U.S. 722, 731 (2002) (“Unfortunately, the nature of language makes it impossible to

capture the essence of a thing in a patent application.”).

44. See Mark A. Lemley, Contracting Around Liability Rules, 100 C

ALIF. L. REV. 463, 468

A5_SEAMAN (DO NOT DELETE) 7/4/2016 4:32 PM

1958 IOWA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 101:1949

injunctive relief to extract compensation significantly in excess of the IP

right’s economic value.

45

Proponents of a liability rule in these situations

assert that “[i]njunction threats often involve a strong element of holdup in

the common circumstance in which the defendant has already invested

heavily to design, manufacture, market, and sell [a] product” that practices

the patented technology.

46

At that point, the infringer “would be willing to

pay much more than he rationally would have negotiated ex ante in order not

to pull the product from the shelves.”

47

Critics of property rules argue that

holdup operates as a “tax” on new high-tech products, which ultimately

impedes growth rather than promoting innovation.

48

Other scholars,

however, have questioned whether holdup is a significant problem on both

empirical and theoretical levels.

49

In sum, the theoretical literature has historically favored protecting IP

rights—particularly patent rights—through property rules. But as explained

(2012) (“The biggest risk of applying property rules in IP cases is holdup.”).

45. See F

ED. TRADE COMM’N, supra note 8, at 58 (“Under some circumstances, the grant or

threat of a permanent injunction can lead an infringer to pay higher royalties than it would pay

in a competitive market for a patented invention.”); see also C

OTTER, supra note 38, at 59

(“[P]atent[ed] holdup involves the strategic use of a patent . . . to extract ex post rents that are

disproportionate to the ex ante value of the invention in comparison with the next-best available

alternative.”); Alexander Galetovic, Stephen Haber & Ross Levine, An Empirical Examination of

Patent Holdup, 11 J.

COMPETITION L. & ECON. 549, 549–50 (2015) (“[T]he patent holdup

hypothesis asserts that patent holders charge licensing royalties to manufacturing firms that

exceed the true economic contribution of the patented technology, thereby discouraging

innovation by manufacturers and hurting consumers.”); Lemley & Shapiro, supra note 10, at 1993

(“[T]he threat of an injunction can enable a patent holder to negotiate royalties far in excess of

the patent holder’s true economic contribution.”).

46. Lemley & Shapiro, supra note 10, at 1993 (emphasis omitted); see also C

OTTER, supra

note 38, at 59 (explaining that the strategy of holdup “rests upon the patent owner’s ability to

obtain an injunction against the distribution of the end product, after the costs of designing,

producing, and distributing the end product have been sunk”).

47. C

OTTER, supra note 38, at 59; see also Lemley & Shapiro, supra note 10, at 1995–2008

(modeling how a patent holder can exploit the cost of switching technologies to obtain licensing

revenue greater than would have occurred in an ex ante negotiation). The holdup problem is

asserted to be particularly acute for widely-adopted technological standards, where a single patent

owner can use the threat of an injunction to “extract unreasonably high royalties from suppliers

of standard-compliant products and services.” Microsoft Corp. v. Motorola, Inc., 696 F.3d 872,

876 (9th Cir. 2012); see also Mark A. Lemley, Ten Things to Do About Patent Holdup of Standards

(and One Not to), 48 B.C.

L. REV. 149, 153–54 (2007).

48. Lemley & Shapiro, supra note 10, at 1993; see also

FED. TRADE COMM’N, supra note 8, at

26 (explaining that “[a]n injunction’s ability to cause patent hold-up . . . can deter innovation by

increasing costs and uncertainty for manufacturers” and “raise prices to consumers by depriving

them of the benefit of competition among technologies”).

49. See generally Einer Elhauge, Do Patent Holdup and Royalty Stacking Lead to Systematically

Excessive Royalties?, 4 J.

COMPETITION L. & ECON. 535 (2008); Golden, Patent Trolls, supra note 4,

at 2148–60; J. Gregory Sidak, Holdup, Royalty Stacking, and the Presumption of Injunctive Relief for

Patent Infringement: A Reply to Lemley & Shapiro, 92 M

INN. L. REV. 714 (2008); see also Galetovic et

al., supra note 45, at 552–54, 570–72 (finding no empirical evidence to support the claim of

holdup for standard-essential patents).

A5_SEAMAN (DO NOT DELETE) 7/4/2016 4:32 PM

2016] PERMANENT INJUNCTIONS IN PATENT LITIGATION 1959

in more detail in the balance of this Article, eBay represents a significant shift

away from a property rule approach, at least for certain types of patent owners.

III. P

ATENTS AND THE RIGHT TO EXCLUDE

This Part chronicles the historic right of patentees to a property rule

excluding others from practicing patented inventions. It then analyzes the

eBay litigation and the Supreme Court’s announcement of a four-factor test

to govern the district courts’ equitable power to grant injunctive relief. Finally,

it addresses the existing literature regarding eBay’s impact on the availability

of permanent injunctions in patent litigation.

A. H

ISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT

Property rules have long predominated in patent law.

50

As Chief Justice

Roberts noted in his concurrence in eBay, since “at least the early 19th

century, courts have granted injunctive relief upon a finding of infringement

in the vast majority of patent cases.”

51

The Patent Act of 1790, passed by the First Congress, granted inventors

“the sole and exclusive right and liberty of making, constructing, using and

vending to others to be used, the . . . invention or discovery.”

52

The earliest

patent laws provided only for remedies at law—that is, recovery of monetary

damages for infringing conduct.

53

Starting in 1819, however, Congress

expressly authorized injunctive relief to preclude future infringement:

[T]he circuit courts of the United States . . . shall have authority to

grant injunctions, according to the course and principles of courts

of equity, to prevent the violation of the rights of any . . . inventors,

secured to them by any laws of the United States, on such terms and

conditions as the said courts may deem fit and reasonable . . . .

54

The current statutory language in § 283 of the Patent Act is remarkably

similar, providing that “courts . . . may grant injunctions in accordance with

50. See supra note 34; see also Frank H. Easterbrook, Intellectual Property is Still Property, 13

H

ARV. J.L. & PUB. POL’Y 108, 109 (1990) (“Patents give a right to exclude, just as the law of

trespass does with real property.”).

51. eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C., 547 U.S. 388, 395 (2006) (Roberts, C.J., concurring).

52. An Act to Promote the Progress of Useful Arts, ch. 7, § 1, 1 Stat. 109, 110 (1790).

53. See 3 W

ILLIAM C. ROBINSON, THE LAW OF PATENTS FOR USEFUL INVENTIONS § 1082,

391–92 (1890) (“The acts of Congress, prior to 1819, made no provision for any suit in equity

by the owner of a patent, nor for his enjoyment of any form of equitable relief in connection with

his action for damages at common law.”); see also Elizabeth E. Millard, Note, Injunctive Relief in

Patent Infringement Cases: Should Courts Apply a Rebuttable Presumption of Irreparable Harm After eBay

Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C.?, 52 S

T. LOUIS U. L.J. 985, 992 (2008) (noting that “the earliest

patent statutes provided only for remedies at law”).

54. An Act to Extend the Jurisdiction of the Circuit Courts of the United States to Cases

Arising Under the Law Relating To Patents, ch. 19, 3 Stat. 481, 481–82 (1819).

A5_SEAMAN (DO NOT DELETE) 7/4/2016 4:32 PM

1960 IOWA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 101:1949

the principles of equity to prevent the violation of any right secured by patent,

on such terms as the court deems reasonable.”

55

Prior to eBay, courts routinely characterized patents as conferring a

property right on their owners.

56

In turn, the right to exclude has been widely

viewed as the “hallmark of a protected property interest”

57

and “one of the

most treasured strands in an owner’s bundle of property rights.”

58

As early as

1852, the Supreme Court declared that the rights conferred by a patent

include “the right to exclude [others] from making, using, or vending the

thing patented, without the permission of the patentee.”

59

The Court’s 1908 decision in Continental Paper Bag Co. v. Eastern Paper Bag

Co. confirmed that patents confer the right to exclude others, even if the

patentee itself has not practiced the patent.

60

In that case, the patent owner,

Eastern Paper Bag Co. (“Eastern”), had purchased a patent on an improved

machine for making paper bags, but Eastern did not use the improved

machine, nor did it license anyone else to do so, as it feared that a competitor

using the improved machine would erode its profits.

61

A competing

manufacturer, Continental Paper Bag Co. (“Continental”), started using a

55. 35 U.S.C. § 283 (2012).

56. See, e.g., Festo Corp. v. Shoketsu Kinzoku Kogyo Kabushiki Co., 535 U.S. 722, 730

(2002) (explaining that the patent laws provide “a temporary monopoly . . . [which] is a property

right”); Fla. Prepaid Postsecondary Educ. Expense Bd. v. Coll. Sav. Bank, 527 U.S. 627, 642

(1999) (noting that patents “have long been considered a species of property”); Dawson Chem.

Co. v. Rohm & Haas Co., 448 U.S. 176, 215 (1980) (noting “the long-settled view that the essence

of a patent grant is the right to exclude”); Hartford-Empire Co. v. United States, 323 U.S. 386,

415 (1945) (stating that it “has long been settled” that “a patent is property, protected against

appropriation both by individuals and by government”); Wilson v. Rousseau, 45 U.S. (4 How.)

646, 674 (1846) (explaining that “[t]he law has thus impressed upon [a patent] all the qualities

and characteristics of property”). The Patent Act provides that “patents shall have the attributes

of personal property.” 35 U.S.C. § 261 (2012).

57. Fla. Prepaid Postsecondary Educ. Expense Bd., 527 U.S. at 643.

58. Loretto v. Teleprompter Manhattan CATV Corp., 458 U.S. 419, 435 (1982); see also

Kaiser Aetna v. United States, 444 U.S. 164, 176 (1979) (describing “the right to exclude” as

“one of the most essential sticks in the bundle of rights that are commonly characterized as

property”); Lemley & Weiser, supra note 33, at 783 (“The foundational notion of property law is

that the ‘right to exclude’ is the essence of a true property right.”); Thomas W. Merrill, Property

and the Right to Exclude, 77 N

EB. L. REV. 730, 730 (1998) (“[T]he right to exclude others is more

than just ‘one of the most essential’ constituents of property—it is the sine qua non.”).

59. Bloomer v. McQuewan, 55 U.S. (14 How.) 539, 549 (1852); see also Herbert F. Schwartz,

Note, Injunctive Relief in Patent Infringement Suits, 112 U.

PA. L. REV. 1025, 1041–42 (1964) (“By the

middle of the nineteenth century, courts generally recognized that the plaintiff was entitled to . . . an

injunction against future infringements for the life of the patent.” (footnotes omitted)).

60. Cont’l Paper Bag Co. v. E. Paper Bag Co., 210 U.S. 405, 429 (1908).

61. Id. at 407, 427–28. According to the trial court, Eastern’s purpose in purchasing the

patent-in-suit was to “lock[ ] up” the technology and thus prevent competitors from using it for

the rest of the patent’s life. See E. Paper Bag Co. v. Cont’l Paper Bag Co., 142 F. 479, 487 (C.C.D.

Me. 1905) (“[Eastern] has never attempted to make any practical use of [the patent], either itself

or through licenses, and apparently its proposed policy has been to avoid this.”).

A5_SEAMAN (DO NOT DELETE) 7/4/2016 4:32 PM

2016] PERMANENT INJUNCTIONS IN PATENT LITIGATION 1961

machine that allegedly infringed on Eastern’s patent.

62

The trial court found

Eastern’s patent valid and infringed, and it granted permanent injunctive

relief.

63

On appeal, Continental argued the trial court erred in granting an

injunction because Eastern had unreasonably failed to use the patented

invention.

64

Continental’s argument was primarily based on the policy claim

that Eastern’s non-use did not promote the constitutional purpose of the

patent system “to promote the progress of science and useful arts.”

65

The

Court rejected this claim, holding that “patents are property” and thus are

“entitled to the same rights and sanctions as other property.”

66

Because a

patent is the “absolute property” of its owner, the Court reasoned, Eastern was

entitled to “insist upon all the advantages and benefits which [patent law]

promises,” including injunctive relief, despite its non-use.

67

It concluded by

explaining that the patent “right can only retain its attribute of exclusiveness

by a prevention of its violation. Anything but prevention takes away the

privilege which the law confers upon the patentee.”

68

After its creation by Congress in 1982, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the

Federal Circuit—which hears all appeals of patent infringement claims

69

—

continued to treat patents as conferring a strong property right to exclude.

70

For instance, it stated in one early decision that “the right to exclude

recognized in a patent is . . . the essence of the concept of property.”

71

Although recognizing that “a district court has discretion whether to enter an

injunction,”

72

the Federal Circuit declared “that an injunction should issue

once infringement has been established unless there is a sufficient reason for

denying it.”

73

In practice, this resulted in a “general rule that courts will issue

permanent injunctions against patent infringement.”

74

Only in rare instances,

62. Cont’l Paper Bag Co., 210 U.S. at 416.

63. Id. at 407. The court also ordered an accounting of Continental’s profits derived from

the infringement. Id.

64. Id. at 422.

65. Id. at 422–23 (citing U.S. C

ONST. art. I, § 8).

66. Id. at 425.

67. Id. at 424.

68. Id. at 430.

69. 28 U.S.C. § 1295(a)(1) (2012).

70. See In re Etter, 756 F.2d 852, 859 (Fed. Cir. 1985) (“The patent right is a right to exclude. . . .

The essence of all property is the right to exclude, and the patent property right is certainly not

inconsequential.”); Carl Schenck, A.G. v. Nortron Corp., 713 F.2d 782, 786 n.3 (Fed. Cir. 1983) (“The

patent right is but the right to exclude others, the very definition of ‘property.’”).

71. Connell v. Sears, Roebuck & Co., 722 F.2d 1542, 1548 (Fed. Cir. 1983) (citation

omitted); see also Dawson Chem. Co. v. Rohm & Hass Co., 448 U.S. 176, 215 (1980) (noting “the

long-settled view that the essence of a patent grant is the right to exclude”).

72. Trans-World Mfg. Corp. v. Al Nyman & Sons, Inc., 750 F.2d 1552, 1564 (Fed. Cir. 1984)

(citation omitted).

73. W.L. Gore & Assocs., Inc. v. Garlock, Inc. 842 F.2d 1275, 1281 (Fed. Cir. 1988).

74. MercExchange, L.L.C. v. eBay, Inc. (MercExchange II), 401 F.3d 1323, 1339 (Fed. Cir. 2005).

A5_SEAMAN (DO NOT DELETE) 7/4/2016 4:32 PM

1962 IOWA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 101:1949

such as to prevent harm to public health or welfare, did courts deny

permanent injunctions.

75

B. eBay v. MercExchange

This Subpart describes the eBay litigation, culminating with the Supreme

Court’s rejection of the “general rule” in favor of injunctive relief and its

replacement with a four-factor test. As explained in more detail below, the

application of this four-factor test represents a significant shift away from

property rules toward liability rules for the enforcement of patent rights.

1. Initial District Court Decision

MercExchange, L.L.C., a failed startup founded by the inventor of the

patent-in-suit,

76

asserted that eBay, Inc., infringed U.S. Patent No. 5,845,265

(“the ‘265 patent”), which claimed a method and apparatus “for an electronic

market designed to facilitate the sale of goods between private individuals by

establishing a central authority to promote trust among participants.”

77

After

a five-week trial, a jury found the ‘265 patent (and one other patent in the

same family as the ‘265 patent) was valid and infringed, and it awarded

MercExchange $35 million in damages.

78

MercExchange subsequently moved for entry of a permanent injunction,

which the district court denied.

79

While recognizing that “the grant of

injunctive relief against the infringer is considered the norm,” the district

court stated that it was required to consider “traditional equitable principles,”

including “(i) whether the plaintiff would face irreparable injury if the

injunction did not issue, (ii) whether the plaintiff has an adequate remedy at

75. See Rite-Hite Corp. v. Kelley Co., 56 F.3d 1538, 1547 (Fed. Cir. 1995) (“[C]ourts have

in rare instances exercised their discretion to deny injunctive relief in order to protect the public

interest.”); City of Milwaukee v. Activated Sludge, Inc., 69 F.2d 577, 593 (7th Cir. 1934) (denying

a permanent injunction that would have required closing Milwaukee’s sewage treatment plan and

dumping untreated sewage into Lake Michigan, thus endangering “the health and the lives of

more than half a million people”). One notable example of a pre-eBay denial of a permanent

injunction occurred in Foster v. American Machine & Foundry Co., where the Second Circuit

affirmed the trial court’s denial of a permanent injunction when a patentee who did not

manufacture a product using the patented technology sought to exclude a manufacturing

infringer. Foster v. Am. Mach. & Foundry Co., 492 F.2d 1317, 1324 (2d Cir. 1974).

76. For a detailed description of MercExchange and its founder, Thomas G. Woolston, who was

also the inventor of the ‘265 patent, see Holte, Trolls or Great Inventors, supra note 4, at 23–30.

77. eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C., 547 U.S. 388, 390 (2006).

78. MercExchange I, 275 F. Supp. 2d 695, 698–99 (E.D. Va. 2003). The district court struck $5.5

million from the jury’s award for eBay’s inducement of a third party to infringe the ‘265 patent,

concluding that it would result in impermissible double counting. Id. at 710. In addition, the jury’s $4.5

million verdict for infringement of another patent-in-suit (U.S. Patent No. 6,085,176) was subsequently

vacated on appeal because that patent was invalid as anticipated. MercExchange II, 401 F.3d at 1333–35

(referring to MercExchange I, 275 F. Supp. 2d at 698–99).

79. MercExchange I, 275 F. Supp. 2d at 710–15. For a summary of the parties’ briefing on

the issue of injunctive relief at the trial court level, see Holte, Misinterpretation of eBay, supra note

4, at 691–95.

A5_SEAMAN (DO NOT DELETE) 7/4/2016 4:32 PM

2016] PERMANENT INJUNCTIONS IN PATENT LITIGATION 1963

law, (iii) whether granting the injunction is in the public interest, and

(iv) whether the balance of the hardships tips in the plaintiff’s favor.”

80

After evaluating these factors, the district court found none of them

weighed in favor of granting an injunction. First, the district court pointed to

“evidence of the plaintiff’s willingness to license its patents, its lack of

commercial activity in practicing the patents, and its comments to the media

as to its intent with respect to enforcement of its patent rights” in concluding

that eBay had rebutted the presumption that MercExchange would suffer

irreparable harm absent an injunction.

81

Second, the district court relied on

MercExchange’s practice of “licens[ing] its patents to others in the past” and

“its willingness to license the patents to the defendants in this case” as

evidence that it had an adequate remedy at law.

82

Third, it held “the public

interest factor equally supports granting an injunction to protect

[MercExchange]’s patent rights, and denying an injunction to protect the

public’s interest in using a patented business-method that the patent holder

declines to practice.”

83

Finally, the district court concluded the balance of

hardships favored eBay because “[a]ny harm suffered . . . by the defendants’

infringement of the patents can be recovered by way of damages.”

84

2. Federal Circuit Decision

MercExchange appealed to the Federal Circuit, which affirmed the jury’s

findings that the ‘265 patent was valid and infringed by eBay in a published

decision in March 2005, but it reversed the district court’s denial of a

permanent injunction.

85

The Federal Circuit first recounted “the general

rule . . . that a permanent injunction will issue once infringement and validity

have been adjudged.”

86

It then concluded that the district court had failed to

“provide any persuasive reason to believe this case is sufficiently exceptional

to justify the denial of a permanent injunction.”

87

In particular, the Federal

Circuit criticized the district court’s reasoning that MercExchange’s

willingness to license its patents meant that it did not suffer irreparable harm

and that it had an adequate remedy at law, stating that offers to license

“should not . . . deprive [MercExchange] of the right to an injunction to

which it would otherwise be entitled. Injunctions are not reserved for

patentees who intend to practice their patents, as opposed to those who

80. MercExchange I, 275 F. Supp. 2d at 711.

81. Id. at 712.

82. Id. at 713.

83. Id. at 714.

84. Id.

85. MercExchange II, 401 F.3d at 1326.

86. Id. at 1338 (citing Richardson v. Suzuki Motor Co., 868 F.2d 1226, 1246–47 (Fed. Cir.

1989)).

87. Id. at 1339.

A5_SEAMAN (DO NOT DELETE) 7/4/2016 4:32 PM

1964 IOWA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 101:1949

choose to license.”

88

It also held that the district court’s “general concern

regarding business-method patents” were “not a sufficient basis for denying a

permanent injunction.”

89

On the issue of damages, the Federal Circuit

declined to overturn the $25 million award for past infringement of the ‘265

patent.

90

3. Supreme Court Decision

On November 28, 2005, the Supreme Court granted eBay’s petition for

writ of certiorari on the issue of permanent injunctive relief.

91

In particular,

the Court explicitly directed the parties to brief and argue “[w]hether this

Court should reconsider its precedents, including Continental Paper Bag Co. v.

Eastern Paper Bag Co., on when it is appropriate to grant an injunction against

a patent infringer.”

92

The appeal attracted significant media attention from

the popular press,

93

and numerous intellectual property scholars, bar

organizations, and high-technology firms filed amicus briefs with the Court.

94

On May 16, 2006, the Court unanimously reversed the Federal Circuit.

95

The Court’s opinion, delivered by Justice Thomas, is succinct—less than five

full pages in the official United States Reports. After summarizing the parties

and procedural history of the case, the Court announced that “[a]ccording to

well-established principles of equity, a plaintiff seeking a permanent

injunction must satisfy a four-factor test.”

96

Specifically, it held that the

patentee must show:

88. Id.

89. Id.

90. Id. at 1326; see also supra note 78 and accompanying text (explaining how the jury’s

verdict was reduced to $25 million).

91. eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C., 546 U.S. 1029 (2005) (granting writ of certiorari).

92. Id. (internal citation omitted).

93. See, e.g., Katie Hafner, Justices Will Hear Patent Case Against eBay, N.Y.

TIMES (Mar. 27, 2006),

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/03/27/technology/27ebay.html (noting that the eBay appeal “has

attracted an unusual amount of public attention in part because of recent attempts by large

corporations to change patent law to lessen the threat posed by so-called nonpracticing patent

holders”); see also Joan Biskupic, Supreme Court Hears eBay Patent Case, USA TODAY, (Mar. 29, 2006, 9:47

PM), http://www.usatoday30.usatoday.com/tech/news/2006-03-29-ebay-case_X.htm.

94. See, e.g., Brief Amici Curiae of 52 Intellectual Property Professors in Support of

Petitioners, eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C., 547 U.S. 388 (2006) (No. 05-130), 2006 WL

1785363; Brief of Various Law & Economics Professors as Amici Curiae in Support of

Respondent, eBay, 547 U.S. 388 (No. 05-130), 2006 WL 639164; Brief of the American Bar Ass’n

as Amicus Curiae Supporting Respondent, eBay, 547 U.S. 388 (No. 05-130), 2006 WL 639167;

Brief of American Intellectual Property Law Ass’n & Federal Circuit Bar Ass’n as Amici Curiae in

Support of Neither Party, eBay, 547 U.S. 388 (No. 05-130), 2006 WL 148639; Brief of Amicus

Curiae Yahoo! Inc. in Support of Petitioner, eBay, 547 U.S. 388 (No. 05-130), 2006 WL 218988;

Brief of I.B.M. Corp. as Amicus Curiae in Support of Neither Party, eBay, 547 U.S. 388 (No. 05-

130), 2006 WL 235006. A summary of the amicus briefs filed in the Supreme Court is available

at Holte, Misinterpretation of eBay, supra note 4, at 691–95.

95. eBay, 547 U.S. at 390.

96. Id. at 391. Several remedies scholars have persuasively argued that the four-factor test

A5_SEAMAN (DO NOT DELETE) 7/4/2016 4:32 PM

2016] PERMANENT INJUNCTIONS IN PATENT LITIGATION 1965

(1) that it has suffered an irreparable injury; (2) that remedies

available at law, such as monetary damages, are inadequate to

compensate for that injury; (3) that, considering the balance of

hardships between the plaintiff and defendant, a remedy in equity

is warranted; and (4) that the public interest would not be disserved

by a permanent injunction.

97

The Court then declared that this four-part test “appl[ied] with equal force to

disputes arising under the Patent Act.”

98

The Court’s opinion acknowledged that patents confer property rights

upon their owners, including “the right to exclude others from making, using,

offering for sale, or selling the invention.”

99

However, it rejected the Federal

Circuit’s reasoning that this right “justifies [the] general rule in favor of

permanent injunctive relief,” asserting—without citing to any authority—that

“the creation of a right is distinct from the provision of remedies for violations

of that right.”

100

Instead, it concluded that “injunctive relief ‘may’ issue only

‘in accordance with the principles of equity.’”

101

The Court held that neither the district court nor the Federal Circuit had

“fairly applied . . . traditional equitable principles in deciding

[MercExchange]’s motion for a permanent injunction.”

102

First, it criticized

the district court for apparently “adopt[ing] certain expansive principles

suggesting that injunctive relief could not issue in a broad swath of cases,”

including when a patent owner did not commercially practice the patented

invention or when it was willing to license the patent-in-suit to others,

declaring that these “categorical rule[s] . . . cannot be squared with the

principles of equity adopted by Congress.”

103

The Court specifically cited its

decision in Continental Paper Bag to support its conclusion that the district

court could not categorically deny injunctive relief to a non-practicing patent

holder.

104

At the same time, it rebuffed the Federal Circuit’s adoption of a

“general rule, unique to patent disputes, that a permanent injunction

[should] issue” absent “exceptional circumstances,” explaining that the

articulated in eBay was in fact not “well-established.” See DOUGLAS LAYCOCK, MODERN AMERICAN

REMEDIES: CASES AND MATERIALS 339 (4th ed. 2012) (concluding that “there was no ‘traditional’

four-part test” for permanent injunctions); Gergen et al., supra note 4, at 207 (explaining how

the eBay decision’s “four-factor test differs from traditional equitable practice in at least three,

and possibly four, significant ways”); Rendleman, supra note 4, at 76 n.71 (noting that

“[r]emedies specialists had never heard of the four-point test” announced in eBay).

97. eBay, 547 U.S. at 391.

98. Id.

99. Id. at 392 (quoting 35 U.S.C. § 154(a)(1) (2006)).

100. Id.

101. Id. (quoting 35 U.S.C. § 283 (2006)).

102. Id. at 393.

103. Id.

104. Id. (citing Cont’l Paper Bag Co. v. E. Paper Bag Co., 210 U.S. 405, 422–430 (1908)).

A5_SEAMAN (DO NOT DELETE) 7/4/2016 4:32 PM

1966 IOWA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 101:1949

Federal Circuit’s departure “in the opposite direction” also was incompatible

with the four-factor test.

105

The Court then vacated and remanded the case to

the district court to apply “the traditional four-factor framework.”

106

This unanimous opinion, however, only thinly veiled an apparent deep-

seated disagreement between the Justices regarding the proper circumstances

for granting permanent injunctions in future patent cases.

107

These diverging

views burst to the forefront in two concurring opinions. In a two-paragraph

concurrence, Chief Justice Roberts, joined by Justices Scalia and Ginsburg,

suggested trial courts would be wise to consider “a page of history” and

continue to grant injunctions in the “vast majority of patent cases” after

eBay.

108

In particular, the Chief Justice noted the difficulty of protecting the

right to exclude “through monetary remedies that allow an infringer to use an

invention against the patentee’s wishes.”

109

In a separate concurrence, Justice Kennedy, joined by Justices Stevens,

Souter, and Breyer, initially expressed agreement with the Chief Justice’s

statement that “history may be instructive in applying [the four-factor] test,”

but immediately proceeded to critique the Chief Justice’s assertion regarding

the difficulty of protecting the right to exclude without an injunction.

110

Justice Kennedy’s concurrence contended that “[b]oth the terms of the

Patent Act and the traditional view of injunctive relief accept that the

existence of a right to exclude does not dictate the remedy for a violation of

that right.”

111

It then asserted that modern patent cases often differed from

historical patent litigation in several important ways, including the role of

non-practicing patentees who employ injunctive relief “as a bargaining tool to

charge exorbitant fees to companies that seek to buy licenses to practice the

patent.”

112

Justice Kennedy’s concurrence also explained that injunctions may

be inappropriate “[w]hen the patented invention is but a small component of

the product the companies seek to produce and the threat of an injunction is

105. Id. at 393–94 (quoting MercExchange II, 401 F.3d 1323, 1339 (Fed. Cir. 2005)).

106. Id. at 394.

107. See James M. Fischer, The “Right” to Injunctive Relief for Patent Infringement, 24 S

ANTA

CLARA COMPUTER & HIGH TECH. L.J. 1, 20 (2007) (“The Court’s decision in eBay, although

presented as a unanimous decision . . . is sufficiently terse, pithy, and fractured by the two

concurrences as to provide some support to practically any conclusion one wishes to draw from

the decision.”); Paul M. Mersino, Note, Patents, Trolls, and Personal Property: Will eBay Auction Away

a Patent Holder’s Right to Exclude?, 6 A

VE MARIA L. REV. 307, 326 (2007) (“The generality in the

[C]ourt’s holding [in eBay] was compounded by the fact that, although it was technically

unanimous, the two concurring opinions were highly divergent on exactly how the holding

should be applied.”).

108. eBay, 547 U.S. at 395 (Roberts, C.J., concurring) (citation omitted).

109. Id.

110. Id. at 395–96 (Kennedy, J., concurring).

111. Id. at 396.

112. Id.

A5_SEAMAN (DO NOT DELETE) 7/4/2016 4:32 PM

2016] PERMANENT INJUNCTIONS IN PATENT LITIGATION 1967

employed simply for undue leverage in negotiations.”

113

Finally, Justice

Kennedy pointed to the “burgeoning number of patents over business

methods,” some of which suffer from “potential vagueness and suspect

validity,” as another reason to potentially deny injunctive relief.

114

4. After Remand

An important part of the eBay litigation—although sometimes

overlooked in the shadow of the landmark Supreme Court decision—is the

decision of the district court after remand. Applying the four-factor test

mandated by the Court’s decisions, the district court again denied injunctive

relief to MercExchange.

115

This opinion is instructive because the district

court’s reasoning has been widely adopted by subsequent courts when

declining to grant injunctive relief to prevailing patentees.

In a detailed written decision issued on July 27, 2007, the district court

found that three of the four eBay factors weighed against an injunction.

116

First, it concluded MercExchange could not demonstrate irreparable harm.

The district court explained that the traditional presumption of irreparable

harm following a finding of infringement did not survive the Supreme Court’s

decision, which “require[d] the [patentee] to demonstrate that it has suffered

an irreparable injury.”

117

MercExchange could not demonstrate such harm,

the court reasoned, because it had “acted inconsistently with defending its

right to exclude” by “follow[ing] a consistent course of licensing its patents to

market participants.”

118

In particular, MercExchange’s “consistent course of

litigating or threatening litigation to obtain money damages . . . indicates that

MercExchange has utilized its patents as a sword to extract money rather than

as a shield to protect its right to exclude.”

119

Thus, it concluded

MercExchange’s patent licensing practice “plainly weighs against a finding of

irreparable harm.”

120

For similar reasons, the district court found

MercExchange had an adequate remedy at law because it had demonstrated

a “consistent desire to obtain royalties in exchange for a license to its

113. Id.

114. Id. at 397.

115. MercExchange L.L.C. v. eBay, Inc. (MercExchange III), 500 F. Supp. 2d 556, 559 (E.D.

Va. 2007).

116. Id. at 569–91.

117. Id. at 569 (emphasis omitted); see also id. (“[E]ven though an affirmed jury verdict

establishes that eBay is a willful infringer . . . , a permanent injunction shall only issue if plaintiff

carries its burden of establishing that, based on traditional equitable principles, the case specific

facts warrant entry of an injunction.”).

118. Id.

119. Id. at 572.

120. Id. at 573. The District Court also noted that MercExchange’s failure to seek

preliminary injunctive relief and its business method patent also weighed against a finding of

irreparable harm. Id. at 574–75.

A5_SEAMAN (DO NOT DELETE) 7/4/2016 4:32 PM

1968 IOWA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 101:1949

intellectual property” and thus could be made whole through monetary

damages.

121

Third, the court found that the “balance of the hardships” factor favored

neither party due to a variety of uncertainties, including eBay’s claimed design

around, the possibility that the ‘265 patent would be invalidated in

reexamination, and the potential of eBay to lose customers if it was forced to

remove the infringing buy-it-now option from its website.

122

Fourth, the

district court determined that the final eBay factor, the public interest,

weighed slightly against entry of an injunction because the public interest

favored damages—a liability rule—rather than an injunction because

MercExchange was “merely seeking an injunction as a bargaining chip to

increase [its] bottom line.”

123

In the court’s judgment, this outweighed “the

public . . . benefits from a strong patent system.”

124

Following denial of a permanent injunction, the district court directed

entry of final judgment that the ‘265 patent was willfully infringed and valid,

and it confirmed the damages award.

125

eBay then launched a second appeal

to the Federal Circuit,

126

but the parties resolved their dispute in February

2008 through an out-of-court settlement in which eBay agreed to purchase

the ‘265 patent (and two other patents) for an undisclosed sum.

127

B. EXISTING LITERATURE ON EBAY’S IMPACT

In the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision, scholars and others

questioned how eBay would affect the availability of injunctive relief in patent

litigation.

128

The existing literature regarding eBay’s impact suggests that

121. Id. at 583 (emphasis omitted).

122. Id. at 583–86.

123. Id. at 588.

124. Id. at 587.

125. MercExchange, L.L.C. v. eBay, Inc. (MercExchange IV), 660 F. Supp. 2d 653, 658–59

(E.D. Va. 2007).

126. Notice of Appeal, MercExchange, L.L.C. v. eBay, Inc., No. 2:01-CV-00736 (E.D. Va.

Dec. 18, 2007), ECF No. 758. eBay’s appeal was docketed as No. 2008-1139.

127. See Press Release, eBay Inc. and MercExchange, L.L.C. Reach Settlement Agreement,

EBAY

(Feb. 28, 2008), http://investor.ebayinc.com/releasedetail.cfm?releaseid=296670.

128. See, e.g., F

ED. TRADE COMM’N, supra note 8, at 217 (noting that eBay “created significant

uncertainty concerning the circumstances under which courts would deny permanent

injunctions”); F. Scott Kieff, Removing Property from Intellectual Property and (Intended?) Pernicious

Impacts on Innovation and Competition, in C

OMPETITION POLICY AND PATENT LAW UNDER

UNCERTAINTY: REGULATING INNOVATION 416, 425 (Geoffrey A. Manne & Joshua D. Wright eds.,

2011) (“In the final analysis, the full impact of the eBay case remains an open question for

debate.”); Crane, supra note 31, at 264 (“In light of eBay, injunctions no longer issue as a matter

of course in infringement cases, but it remains to be seen just how wide the impact of eBay will

be.”); The Supreme Court, 2005 Term—Leading Cases, 120 H

ARV. L. REV. 125, 337 (2006) (asserting

that “eBay raises more questions about the grant of permanent injunctions than it answers” and

that “the opinion leaves patent holders to speculate whether fewer permanent injunctions against

infringers will issue in a post-eBay world”).

A5_SEAMAN (DO NOT DELETE) 7/4/2016 4:32 PM

2016] PERMANENT INJUNCTIONS IN PATENT LITIGATION 1969

while permanent injunctions are still commonly granted, certain types of

patent disputes have largely shifted from a property rule to a liability rule.

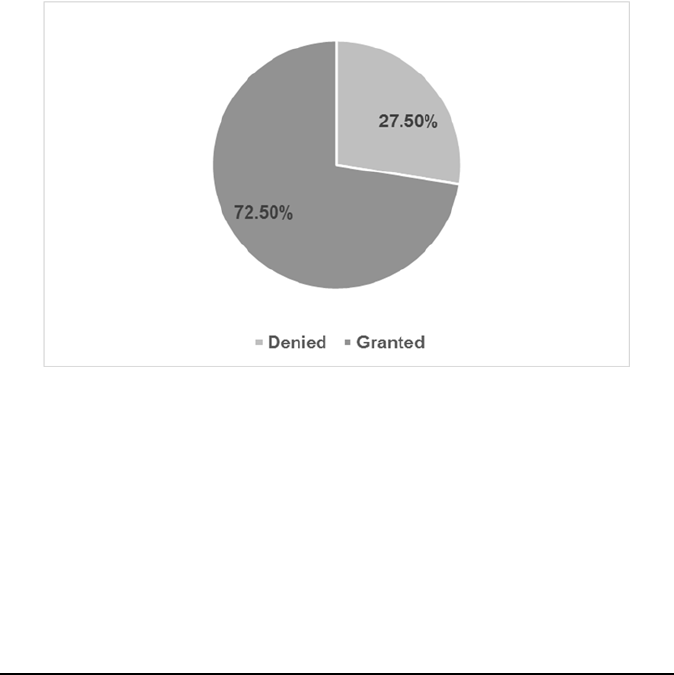

Several previous studies have found that prevailing patentees still receive

permanent injunctions approximately three-quarters of the time following

eBay. One article published in 2008 found that district courts awarded

permanent injunctions in approximately 78% of cases.

129

Another study of

injunction decisions through May 2009 disclosed that permanent injunctions

were granted 72% of the time.

130

Similarly, in a 2012 article, Colleen Chien

and Mark Lemley reported that “courts have granted about 75% of requests

for injunctions, down from an estimated 95% pre-eBay.”

131

A recent paper by

Kirti Gupta and Professor Jay Kesan found that permanent injunction

motions between eBay and 2012 were granted 80% of the time.

132

Finally, a

database of permanent injunction decisions hosted by the University of

Houston Law Center’s Institute for Intellectual Property and Information Law