NATIONAL 5-YEAR

STRATEGY FOR COMBATING

ILLEGAL, UNREPORTED, AND UNREGULATED FISHING

2022-2026

Report prepared by:

U.S. Interagency Working Group on IUU Fishing

Member Agencies:

National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration

U.S. Department of State

U.S. Coast Guard

Council on Environmental Quality

Director of National Intelligence, Representative of

National Security Council

Office of Management and Budget

Office of Science and Technology Policy

Office of the U.S. Trade Representative

U.S. Agency for International Development

U.S. Department of Agriculture

U.S. Department of Defense

U.S. Department of Homeland Security

U.S. Department of Justice

U.S. Department of Labor

U.S. Department of the Treasury

U.S. Federal Trade Commission

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement

U.S. Navy

REPORT TO CONGRESS

NATIONAL 5-YEAR STRATEGY FOR COMBATING

ILLEGAL, UNREPORTED, AND UNREGULATED

FISHING (2022-2026)

Developed pursuant to: National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020

(PUBLIC LAW No: 116-92, S.1790)

Janet Coit

Assistant Administrator for Fisheries

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Dr. Richard W. Spinrad

Under Secretary of Commerce

for Oceans and Atmosphere

and NOAA Administrator

THE NATIONAL DEFENSE AUTHORIZATION ACT FOR FISCAL YEAR 2020 (PUBLIC

LAW No: 116-92, S.1790) INCLUDED THE FOLLOWING LANGUAGE

(a) STRATEGIC PLAN.—Not later than 2 years after the date of the enactment of this title, the

Working Group, after consultation with the relevant stakeholders, shall submit to the Committee

on Commerce, Science, and Transportation of the Senate, the Committee on Foreign Relations of

the Senate, the Committee on Appropriations of the Senate, the Committee on Transportation

and Infrastructure of the House of Representatives, the Committee on Natural Resources of the

House of Representatives, the Committee on Foreign Affairs of the House of Representatives,

and the Committee on Appropriations of the House of Representatives a 5-year integrated

strategic plan on combating IUU fishing and enhancing maritime security, including specific

strategies with monitoring benchmarks for addressing IUU fishing in priority regions.

THIS REPORT RESPONDS TO THE ACT’S REQUEST.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

I.

Executive Summary

5

II.

Introduction

7

III.

Strategic Objective 1: Promote Sustainable Fisheries

Management and Governance

9

IV.

Strategic Objective 2: Enhance the Monitoring, Control, and

Surveillance of Marine Fishing Operations

14

V.

Strategic Objective 3: Ensure Only Legal, Sustainable, and

Responsibly Harvested Seafood Enters Trade

18

VI.

Conclusion

21

Appendix A: Priority Regions

A1-1

Appendix B: Priority Flag States

A2-1

Appendix C: Working Group Membership

A3-1

5

I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Maritime Security and Fisheries Enforcement Act of December 2019 (Maritime SAFE Act)

directed 21 federal agencies to establish an Interagency Working Group on Illegal, Unreported,

and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing to serve as the central forum to coordinate and strengthen their

efforts to counter IUU fishing and related threats to maritime security. This National Strategy

for Combating Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated Fishing establishes the Working Group’s

priorities to combat IUU fishing, curtail the global trade in seafood and seafood products derived

from IUU fishing, and promote global maritime security. This Strategy provides a framework

for coordination for the next five years among the relevant U.S. Government (USG) agencies, in

partnership with other governments and authorities, seafood industry, academia, and

nongovernmental (NGO) stakeholders that will be key in continuing to make tangible progress in

addressing IUU fishing and carrying out a shared vision for stewardship of marine resources. It

also supports the objectives outlined in the President’s National Security Memorandum on

Combating Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated Fishing and Associated Labor Abuses.

For decades, IUU fishing has been a global problem affecting ocean ecosystems, threatening

economic and food security, and putting law-abiding fishermen and seafood producers at a

disadvantage. The United States has been a leader in combating IUU fishing and will continue to

promote sustainable fisheries management, effective fisheries enforcement, and monitoring of

the trade of fish and fish products. We work at regional and international levels, including

through the use of key domestic tools, to improve fisheries management and combat IUU fishing

on the high seas and within other countries’ jurisdictions. This Strategy includes and builds on

existing activities with new initiatives to form a comprehensive set of actions to address IUU

fishing and associated forced labor, including preventing importation of IUU fish and fish

products or those associated with forced labor.

The Maritime SAFE Act charged the Working Group with developing priority regions and

priority flag states to be the focus of assistance coordinated by the Working Group. The Act

defines “priority regions” as those “at high risk for IUU fishing activity or the entry of illegally

caught seafood into the markets of countries in the region; and in which countries lack the

capacity to fully address the illegal activity.” A priority flag state is defined as a country whose

vessels are “actively engaged in, knowingly profit from, or are complicit in IUU fishing” and, at

the same time, “is willing, but lacks the capacity, to monitor or take effective enforcement action

against its fleet.”

Through the Working Group, the United States aims to employ a coordinated, cohesive, and

regionally appropriate approach to combating IUU fishing and related threats to maritime

security in priority regions and priority flag states. The Working Group developed a

comprehensive, tiered list of 12 priority regions intended to focus USG capacity building,

training, and information sharing efforts to combat IUU fishing and enhance maritime security.

Within these priority regions, the Working Group selected five priority flag states and

administrations with which to pursue new projects and initiatives to support ongoing counter-

IUU fishing efforts: Ecuador, Panama, Senegal, Taiwan, and Vietnam. These five flag states or

administrations were not selected as priorities because they are the worst IUU fishing offenders.

Rather, each flag state or administration has demonstrated a willingness to and interest in taking

6

effective action against IUU fishing activities associated with its vessels. The United States aims

to assist these governments and authorities to become self-sufficient, regional leaders in the fight

against IUU fishing. The United States will engage with additional flag states and continue in

this manner with the goal of building a coalition across the globe that works in tandem to prevent

and eliminate IUU fishing.

The United States will work to build positive, cooperative partnerships globally, but particularly

within the priority regions and with the priority flag states and administrations to support and

enhance both ongoing and new counter-IUU fishing efforts. These efforts are organized under

three strategic objectives we are advancing to combat IUU fishing:

1) Promote Sustainable Fisheries Management and Governance – We will continue to

collaborate with other countries, authorities, and stakeholders and within international

and regional organizations to ensure fisheries management and conservation practices are

effective and science-based. We will advance well-managed fisheries that support the

food security, livelihoods, and sustainable development of communities around the

world, particularly in developing countries. Through capacity building and other efforts,

we will promote comprehensive fisheries management and governance structures,

including enforcement mechanisms with robust and effective laws, to encourage

compliance and guard against IUU fishing.

2) Enhance the Monitoring, Control, and Surveillance of Marine Fishing Operations –

We will continue aggressively conducting at-sea monitoring, control, and surveillance

operations to compel compliance with U.S. law and international fisheries conservation

and management measures. We will improve coordination and information sharing

across intelligence, enforcement, and regulatory agencies, as well as foreign partners and

non-governmental organizations (NGOs), to increase enforcement effectiveness. We will

prioritize enforcement efforts against IUU fishing networks, including transnational

criminal organizations. We will promote the adoption of at-sea enforcement provisions

in multilateral agreements. We will help improve global enforcement efforts by

increasing partner capacity and through coordinated operations with like-minded nations.

3) Ensure Only Legal, Sustainable, and Responsibly Harvested Seafood Enters

Trade – We will use our position as a major seafood-consuming and fishing nation to

support collective efforts to ensure the effective conservation and management of

international fisheries. We will work to ensure that imported seafood is safe, legal, and

comes from sustainably managed fisheries. We will also work to identify and address

labor abuses, including forced labor, throughout the seafood supply chain.

This Strategy is a product of a series of interagency discussions among the Working Group

members, including planning sessions that focused on USG work that is underway or planned for

enhancing maritime security and combating IUU fishing in the priority regions and flag states

and administrations. It was also informed by comments from NGOs and industry associations

submitted in fall 2021. In this Strategy, we emphasize a broadening of USG efforts and

enhanced coordination and collaboration across the Working Group agencies, as well as

7

collaboration with foreign partners and nongovernmental organizations. For each of the three

strategic objectives, we identified a wide range of actions that can build on existing efforts or

that we plan to initiate in the next five years. These include specific programs that focus on

particular countries, territories, and entities, in priority regions and flag states as we seek to target

our work and build over time a global network that can support broad local, regional, and

international efforts to combat IUU fishing. We also include efforts that the USG continues to

undertake at a regional or international level, as well as identify the key domestic tools the

United States uses to bring about improvements in fisheries management in other countries or

prevent products of IUU fishing from being imported into the United States. Finally, we identify

monitoring benchmarks for the strategic objectives to help assess progress in the priority regions

and priority flag states and administrations. Progress on this Strategy within the five-year period

will depend on the availability of resources (both in terms of funding and personnel) of all

relevant agencies, as well as engagement by key private sector partners, partner governments and

authorities, and support from U.S. stakeholders.

II. INTRODUCTION

IUU fishing is a global problem that threatens ocean ecosystems and sustainable fisheries. It also

threatens our economic security and the natural resources that are critical to global food security,

deprives scientists of data needed to inform sound fisheries conservation and management

decisions, and puts law-abiding fishermen and seafood producers in the United States and abroad

at a disadvantage.

Over the past two decades, the United States has been a leader in building an expansive toolbox

for countries and partners—individually and collectively—to address IUU fishing, bringing

world-wide recognition to the issue through international fora and making progress through

major domestic initiatives such as the National Plan of Action of the United States of America to

Prevent, Deter, and Eliminate Illegal, Unregulated, and Unreported Fishing (NPOA-IUU)

1

and

the Presidential Task Force on Combating IUU Fishing and Seafood Fraud. Through this work,

we have improved our knowledge of how we, as the different components of the USG, need to

work collaboratively to understand and address IUU fishing. We recognize even more clearly

that addressing IUU fishing is not just about fish: it is a multi-faceted problem that covers other

core policy concerns, including human rights, food security, and maritime security.

Our improved knowledge and understanding has prepared us to fulfill a new mandate, the

Maritime SAFE Act, which became law on December 20, 2019 and supports a “whole-of-

government approach across the Federal Government to counter IUU fishing and related threats

to maritime security.” It seeks to achieve this through a number of means, including improving

data sharing that enhances surveillance, advancing effective enforcement and prosecution against

IUU fishing, supporting coordination and collaboration, increasing and improving global

transparency and traceability across the seafood supply chain, responding to poor working

conditions and labor abuses in the fishing industry, improving global enforcement operations,

and preventing the use of IUU fishing as a financing source for transnational organized groups.

1

https://2001-2009.state.gov/documents/organization/43101.pdf

8

Part II of the Maritime SAFE Act establishes a collaborative interagency Working Group to

strengthen maritime security and combat IUU fishing. In June 2020, this group met for the first

time (see Appendix C for additional details about the Working Group’s leadership and

membership). The Working Group created the following subgroups to carry out specific

activities to fulfill the Working Group’s mandated responsibilities:

Maritime Intelligence Coordination

Public-Private Partnerships

Labor in the Seafood Supply Chain

Gulf of Mexico IUU Fishing

Priority Regions and Flag States

As a part of the process for developing this Strategy, the Working Group first identified the

priority regions and priority flag states, as defined under section 3552(b) of the Maritime SAFE

Act. To select the priority regions, the Working Group assessed different regions around the

world through a framework that considered information about recent or egregious cases of IUU

fishing in each region; the diverse coastal countries’, territories’, and entities’ institutional and

operational capacity to deal with IUU fishing; and how the countries, territories, and entities

within the region participate in the seafood supply chain and global markets. Based on this

analysis, the Working Group developed a comprehensive, tiered list of 12 priority regions

intended to focus USG capacity building, training, and information sharing efforts to combat

IUU fishing and enhance maritime security (see Appendix A for the priority regions).

With an understanding of the global picture of IUU fishing, the Working Group evaluated

several additional criteria to better understand the IUU fishing problem in each of the flag states

and administrations within these 12 priority regions, including IUU fishing activities by their

vessels, their institutional and operational capacity to monitor and police their fleets and

exclusive economic zones (EEZs) effectively, and their willingness to work with the United

States to address IUU fishing activities by their vessels. Based on this analysis, the Working

Group selected the following five priority flag states and administrations from the priority

regions with which to pursue projects and initiatives to support counter-IUU fishing efforts:

Ecuador, Panama, Senegal, Taiwan, and Vietnam (see Appendix B). These five were not

selected as priorities because they are the worst IUU fishing offenders. Rather, each has

demonstrated a willingness and interest to take effective action against IUU fishing activities

associated with its vessels. Ongoing and new counter-IUU fishing efforts will be supported and

enhanced by a positive, cooperative partnership with the United States. The relationships with

these flag states and administrations are expected to lead directly to meaningful progress on

combating IUU fishing, as well as support future partnerships with other countries and partners

that expand the reach of U.S. efforts.

The United States has established the following three strategic objectives to combat IUU fishing

and to address related maritime security threats at a global level, with specific efforts under each

objective that are focused in the priority regions and flag states and administrations:

1. Promote sustainable fisheries management and governance.

2. Enhance monitoring, control, and surveillance of marine fishing operations.

9

3. Ensure only legal, sustainable, and responsibly harvested seafood enters trade.

Over the next 5 years, the United States will use these strategic objectives to develop projects

and initiatives to combat IUU fishing within the priority regions and in each of the priority flag

states and administrations. U.S. activities will be tailored to both the specific needs of each

region or flag state or administration and the range of U.S. projects and activities already

underway. We will also make full use of existing domestic tools, technologies, and our ongoing

efforts to advance guidance, conservation and management measures, and cooperation in

international fora to achieve these strategic objectives. Monitoring benchmarks are identified

within each strategic objective, which were designed to track progress in combating IUU fishing

and enhancing maritime security, particularly in the priority regions and flag states and

administrations.

The efforts of the Working Group align closely with the President’s National Security

Memorandum (NSM) on Combating Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated Fishing and

Associated Labor Abuses. Specifically, the NSM directs agencies to increase coordination

among themselves and with diverse stakeholders to work towards ending forced labor and other

crimes or abuses in IUU fishing; promote sustainable use of the oceans in partnership with other

nations and the private sector; and advance foreign and trade policies that benefit U.S. seafood

workers.

III. STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE 1: PROMOTE SUSTAINABLE FISHERIES

MANAGEMENT AND GOVERNANCE

The foundation for combating IUU fishing is ensuring that coastal and flag states have processes

and frameworks in place to manage the fish stocks they harvest sustainably. Because many fish

and other marine wildlife cross national boundaries, the manner in which other countries and

authorities manage shared marine resources can directly affect the status of fish stocks and

protected or endangered species of importance to the United States. The first step is ensuring

that, individually or collectively, countries and authorities have put in place the basic policies,

laws, and regulations for the responsible conservation and management of fisheries resources.

This requires multifaceted efforts, including determining and monitoring the biological status of

stocks, implementing science-based harvest limits and accountability measures, minimizing

bycatch, providing for adequate enforcement, and combining these efforts to implement

ecosystem-based fisheries management. Just because a fish stock is harvested legally may not

mean that it is harvested sustainably, and enforcement is only meaningful when there are

effective laws and regulations in place to begin with. We will undertake a range of actions to

accomplish this strategic objective. For some of these actions, we identify the country or

administration and the type of work, but we will also seek to implement them in additional

countries, where appropriate, as resources become available.

In priority regions and flag states or administrations

1. In partnership with academia and NGOs, assess the scientific, legal, regulatory, and

operational systems of the countries and authorities in the priority regions for managing

10

marine fisheries to understand their gaps and needs and where and how to focus technical

assistance.

a. Recent public attention and U.S. initiatives have focused on distant-water fishing

off the coastal states of South America, particularly around Ecuador. We will

organize periodic meetings to bring together U.S. entities involved in countering

IUU fishing in or near Ecuador, including agencies, NGOs, and academia, to

share information, successes, and failures; find areas of coordination; and avoid

duplicating efforts. Such meetings will include the government and other sectors

of Ecuador as appropriate. In addition, the United States is entering a

memorandum of understanding (MOU) for collaboration in the Eastern Tropical

Pacific Marine Corridor (CMAR) with the governments of Colombia, Ecuador,

Panama, and Costa Rica.

b. We will work with Panama, interested parties in academia, and NGOs to assess

the fishing (harvesting and carrier) vessel monitoring and control systems within

Panama and use the assessment to identify ways to help build the governance and

operational capacity of Panama.

c. Vietnam has demonstrated a commitment to improving its fisheries management

and governance structures despite challenges in policy coordination between its

central and regional governments. We will work with Vietnam to help develop

coordination mechanisms modeled on U.S. regional fishery management councils

to achieve better alignment and buy-in across all levels of government.

d. We will aim to replicate a recent Department of State Bureau of International

Narcotics and Law Enforcement project in the Caribbean, Central America, and

South America regions that provides baseline information on gaps in

understanding around country law enforcement and legislative capacity on IUU

fishing. The current project analyzes the scope of IUU fishing–related legislation

in the region, identifies government-backed malign actors perpetrating IUU

fishing, assesses crimes associated with IUU fishing, and collects local anecdotes

on the adverse impacts of IUU fishing in the region. Current priority countries

include Costa Rica, Ecuador, Panama, Guyana, Jamaica, Suriname, Chile,

Argentina, and Uruguay.

2. Enhance U.S. efforts to improve the capacity of coastal states and authorities to manage

their domestic fisheries and to combat IUU fishing, both by building the political will to

devote resources to these issues and by providing information, equipment, and expertise.

a. The United States and Taiwan have committed to explore opportunities to

conduct combined security and law enforcement operations in the Indo-Pacific

region through an MOU between the Taipei Economic and Cultural

Representative Office in the United States and the American Institute in Taiwan.

Under this MOU, we will increase professional exchanges between Taiwan Coast

Guard and U.S. Coast Guard law enforcement officers; explore similarities

11

between law enforcement teams, authorities, and jurisdictions; and jointly

contribute to combating the increasingly complex transnational IUU fishing

problem in the Indo-Pacific region.

b. We will help to improve fisheries management in Senegal through the U.S.

Agency for International Development (USAID) Feed the Future Dekkal Geej

(DG) project. The five-year $15 million project is improving the sustainability of

Senegal’s artisanal fisheries sector with an emphasis on co-management practices,

data collection and analysis, policy support, food security, and resiliency.

Additionally, the DG project helps Senegalese stakeholders from the national to

the village level to detect and deter IUU fishing.

3. Develop best practices for foreign licensing and recommendations on the contents of a

model fishing access agreement to ensure adequate oversight, transparency, and

accountability of foreign vessels. Robust access agreements and the capacity to monitor

them minimize the risk of IUU fishing and overexploitation by distant-water fleets

operating in coastal state EEZs. In the Tier 1 and Tier 2 priority regions, we will work

with coastal states and authorities to apply the best practices and model access

agreements to their respective EEZs by providing advice on laws and policies that will

enable effective governance and law enforcement in their EEZs. We will also encourage

nations to demarche the flag states that have foreign fishing fleets that violate fisheries

laws and regulations in their territorial seas and EEZs.

4. Partner with NGOs, media outlets, and academia to promote sound, fact-based journalism

and build journalistic capacity to report and educate the public on the importance of

sustainable fisheries management, expose known instances and actors involved in IUU

fishing, and highlight any clear and actionable intersections with distant water fishing,

flags of convenience, and forced labor.

5. Encourage nations in priority regions and priority flag states and administrations to adopt,

or update any existing, National Plan of Action on counter–IUU fishing and update our

own to serve as a model.

At the international and regional levels

6. Continue championing within regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs)

effective, science-based conservation and management measures and stronger and more

transparent compliance schemes.

a. RFMOs have put in place a range of conservation and management measures

intended to support the long-term sustainability of the resources under their

mandates, as well as monitoring, control, and surveillance (MCS) measures to

ensure compliance with these rules. We will press for RFMOs to fill any gaps in

management and MCS measures, or to strengthen and enhance those already in

place, particularly measures for fisheries data collection and reporting, monitoring

and controlling transshipment, mitigating bycatch of protected species, tracking

12

trade of fish and fish products, and enabling high seas boarding and inspection.

We will also work to ensure that RFMO port state measures schemes are

consistent with the Agreement on Port State Measures (PSMA). Where there are

gaps in management of particular species, we will seek to have the relevant

RFMO address the gaps or, where an RFMO is lacking, press for the formation of

a management body.

7. Advance policies and programs through the Food and Agriculture Organization of the

United Nations (FAO) that promote ecosystem-based fisheries management and ensure

the long-term sustainability of fisheries, both small-scale and industrial. Continue to lead

the development of voluntary and binding instruments that strengthen global fisheries

management.

a. Champion the implementation of the international guidelines on transshipment

recently developed by FAO that outline best practices and help to increase

monitoring to close loopholes that facilitate IUU fishing.

b. Continue to work toward full implementation of the Asia-Pacific Economic

Cooperation’s (APEC) Roadmap to Combat IUU Fishing through robust

participation in the Oceans and Fisheries Working Group (OFWG) of APEC.

Participate in the inter-sessional working group that OFWG established to address

current gaps in the implementation plan. Furthermore, the United States will

continue to demonstrate leadership on IUU fishing in APEC through the hosting

and co-sponsorship of projects that fall within the purview of the Roadmap to

Combat IUU Fishing. This leadership will be even more on display in 2023, when

the United States will be the APEC host country.

Use of existing domestic tools

8. Continue implementing the international provisions of the High Seas Driftnet Fishing

Moratorium Protection Act.

2

9. Continue implementing the international provisions of the Marine Mammal Protection

Act.

3

Monitoring Benchmarks: To assess progress in fisheries management frameworks within

priority regions, we will evaluate the extent of improvements in fisheries governance of coastal

states and authorities in the priority regions, including new fisheries laws, fisheries management

plans, application of effective MCS mechanisms, and the mechanisms for taking enforcement

actions. To assess priority flag states’ and administrations' progress in controlling their

respective distant water fleets, we will examine, where applicable, their improvements in

fisheries governance, with particular focus on new laws and application of effective MCS

mechanisms. We will select specific metrics for assessing progress in a given priority region or

2

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/international/international-affairs/report-iuu-fishing-bycatch-and-shark-catch

3

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/foreign/marine-mammal-protection/noaa-fisheries-establishes-international-

marine-mammal-bycatch-criteria-us-imports

13

priority flag state or administration that take into account the unique needs and circumstances

within each, including the variability in fisheries governance frameworks. These metrics will

draw from the following list, which may also be augmented by additional metrics appropriate to

a given priority region or flag state or administration:

Accession to and/or progress made in implementing international instruments, including,

but not limited to: PSMA,

4

NPOAs on combating IUU fishing, Regional Plans of Action

to Promote Responsible Fishing Practices, the Global Record of Fishing Vessels,

Refrigerated Transport Vessels and Supply Vessels (Global Record),

5

and the Agreement

to Promote Compliance with International Conservation and Management Measures by

Fishing Vessels on the High Seas (Compliance Agreement).

6

Increase in the number of countries joining or cooperating in bilateral and/or regional

fisheries management agreements, and bilateral or multilateral IUU fishing enforcement

agreements.

Increase in the uptake and implementation of vessel monitoring system (VMS) programs,

centralized VMS reporting, and/or other vessel monitoring systems.

Increase in the availability of information regarding the proportion of foreign-owned

fleets and/or flag vessels operating in EEZs (e.g., fishing access agreements, reports of

incursions, vessels flagged to states with known IUU fishing concerns).

In addition to the above quantitative metrics, we will also use qualitative assessment questions,

such as:

Have countries implemented or expressed an intention to join the PSMA?

Did U.S. activities result in new (or changes to existing) fishing access agreements so that

key coastal states and authorities have better oversight, transparency, and accountability

of foreign vessels?

Did support from the United States result in improvements in the regulation and

monitoring of transshipment activities in the Tier 1 and Tier 2 priority regions (such as

establishment of a transshipment monitoring regime with observers, pre-notification,

post-transshipment reporting, and VMS)?

We will also assess progress made within RFMOs to strengthen conservation and management

measures essential to sustainable fisheries management, such as comprehensive MCS measures,

bycatch mitigation measures, and trade-tracking mechanisms. Finally, we will take into account

fisheries management and enforcement improvements made within countries identified under the

High Seas Driftnet Fishing Moratorium Protection Act or improvements in bycatch mitigation

measures brought about by the import provisions of the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

4

https://www.fao.org/port-state-measures/en/

5

https://www.fao.org/global-record/en/

6

https://www.fao.org/iuu-fishing/international-framework/fao-compliance-agreement/en/

14

IV. STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE 2: ENHANCE THE MONITORING,

CONTROL, AND SURVEILLANCE OF MARINE FISHING OPERATIONS

In the vast open spaces of the world’s oceans, MCS of marine fishing operations is critical to

ensure compliance with national and international fishing rules, regulations, and conventions.

Without effective MCS programs, there is little deterrence against IUU fishing. We will improve

MCS coordination within the United States and with our international partners to increase the

risks and costs of IUU fishing, hold flag states and administrations accountable for the actions of

their fishing fleets, and improve the capacity of countries in priority regions to protect their

respective sovereignty. We will undertake a range of actions to accomplish this strategic

objective.

In priority regions and flag states and administrations

1. Collaborate and coordinate with foreign navies, coast guards, and other enforcement

agencies to optimize our collective capacity to design and implement effective MCS

programs and improve the process for receiving and responding to reports of illicit

activity, investigations, and the legal infrastructure to adjudicate IUU fishing cases.

a. Prioritize fisheries enforcement trainings in priority regions and flag states or

administrations to build comprehensive enforcement programs, including any

necessary legal mechanisms, for conducting investigations, the use of information

from whistleblowers, and electronic evidence collection and computer forensics

techniques.

b. Deliver training to improve the capability of partner law enforcement personnel

involved in complex investigations related to IUU fishing that include

international matters including demarches, financial issues, government

corruption, and other enforcement actions.

c. Continue to leverage the Code of Conduct Concerning the Repressing of Piracy,

Armed Robbery against Ships, and illicit Maritime Activity in West and Central

Africa (Yaoundé Code of Conduct)

7

to address fisheries governance issues in the

Gulf of Guinea region and seek opportunities to replicate the Yaoundé Code of

Conduct and associated African Maritime Law Enforcement Partnership

(AMLEP)

8

phased trainings, exercises, and legal interoperability studies, as well

as regional information sharing centers, in other Tier 1 as well as Tier 2 priority

regions.

7

https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/OurWork/Security/Documents/code_of_conduct%20signed%20from%20

ECOWAS%20site.pdf

8

https://www.africom.mil/what-we-do/security-cooperation/africa-maritime-law-enforcement-partnership-amlep-

program#:~:text=The%20African%20Maritime%20Law%20Enforcement,combined%20maritime%20law%20enfor

cement%20operations.

15

d. Continue to support ongoing work that focuses on information gathering and law

enforcement and legislation/law-making capacity building in the maritime

security space, including building capacity to address crimes associated with IUU

fishing.

2. Prioritize establishing new bilateral enforcement agreements, commonly referred to as

“shiprider agreements,” with key countries and authorities in Tier 1 and Tier 2 priority

regions, as well as with priority flag states and administrations. Similarly, add counter-

IUU fishing provisions to existing shiprider agreements.

a. The existing U.S.-Senegal bilateral enforcement agreement presents an

opportunity for the United States to partner with a priority flag state to

demonstrate commitment in the Tier 1 priority region of the Gulf of Guinea where

IUU fishing has historically occurred relatively unopposed. The United States

will find opportunities to use this bilateral agreement to help protect Senegalese

fisheries resources and, in turn, display to the region the value of collaboration

with the United States in the fight against IUU fishing.

3. Continue to seek opportunities to include counter–IUU fishing aspects in multilateral at-

sea exercises with partner navies and coast guards.

a. Maximize opportunities to conduct multi-agency training sessions to reinforce the

United States’ position on combating IUU fishing and translate best practices

across partner agencies. This effort will include synchronizing IUU fishing

training materials among agencies to form a consistent, whole-of-government

message when engaged in capacity building operations.

b. Incorporate counter–IUU fishing subject matter experts and relevant personnel

from partner agencies into the multinational, security-focused, multi-dimensional

exercises that take place globally.

c. Incorporate counter–IUU fishing subject matter experts and relevant personnel

from partner agencies into the multinational Maritime Training Activities (MTA),

for example, as was done for the 2021 MTA exercise Sama between the

Philippines, Japan, France, and the United States. Look for opportunities to share

complex at-sea training to strengthen multilateral forces’ ability to work together,

building partnerships and interoperability between foreign navy and coast guard

ships and aircraft.

To leverage technologies and information sharing

4. Improve information sharing within and among our foreign partners by building a strong

international network to share information that supports maritime enforcement efforts.

a. Pursue the use of existing multilateral organizations—such as RFMOs, regional

coast guard forums, UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), and the

16

International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL)—as platforms for

sharing information for maritime enforcement.

b. Develop standards and, where necessary, bilateral and multilateral agreements to

advance information sharing.

c. Promote the Maritime Information Sharing (MIS) initiatives led by the National

Maritime Intelligence-Integration Office (NMIO) to develop unclassified

collaborative data sharing processes and capabilities that enhance regional

maritime domain awareness and maritime security. Also, build consensus in the

interagency on the best U.S.-sponsored IT systems and tools for better uniformity

and consistency in international collaboration efforts worldwide.

d. Use the Department of Defense’s Maritime Security Initiative to enhance

maritime detection capabilities of eligible countries within their EEZs, increase

maritime domain awareness in Tier 1 and Tier 2 priority regions, and develop a

common operating picture for regional information sharing.

5. Establish and improve the legal and infrastructure frameworks to allow for sharing of

information and data with civil society, NGOs, and the private sector, as appropriate, on

IUU fishing and other connected transnational organized illegal activities, so that we can

better leverage external resources. This could involve setting up memoranda of

understanding or information sharing agreements with particular entities to be able to

share information, as appropriate.

To enhance coordination and collaboration within the USG

6. Maintain IUU fishing as an intelligence collection priority within the U.S. intelligence

community. Intelligence collection efforts will focus on vessels and economic activity

connected to transnational criminal networks engaged in IUU fishing and associated

threats to maritime security including piracy, narcotics smuggling, and human trafficking,

including forced labor.

7. Coordinate law enforcement operations and investigations across U.S. federal agencies,

combining unique capabilities, resources, and authorities into a whole-of-government

effort to identify, track, and target IUU fishing operations and actors most effectively and

efficiently. Coordinate and focus Department of Defense, Department of State, Coast

Guard, and USAID international capacity building authorities and resources on counter–

IUU fishing priority outcomes and objectives. Make use of established region-specific

working groups on IUU fishing and maritime domain awareness to interface regularly

with regional partners—such as the working groups hosted by Combatant

Commanders—and thereby synchronize to make standardized and more efficient

engagement with our partners on these topics.

Monitoring Benchmarks: To assess progress in combating IUU fishing in priority regions and

deterring IUU fishing by vessels of priority flag states and administrations, we will evaluate

17

whether or how the capacity to monitor and take enforcement action has improved due to USG

efforts. In general, we will assess improvements in MCS and enforcement capacity through the

mechanisms for information sharing established or improved upon within a region,

improvements in enforcement cooperation, establishment of multilateral enforcement

arrangements, and reduced incidences of IUU fishing and crimes associated with IUU fishing.

We will select specific metrics for assessing progress in a given priority region or priority flag

state or administration that take into account the unique needs and circumstances within each,

including the variability in MCS and enforcement capacity among them. These metrics will

draw from the following list, which may also be augmented by additional metrics appropriate to

a given priority region or priority flag state or administration:

Increase in the number of bilateral enforcement agreements and similar regional

cooperation arrangements related to IUU fishing and maritime security.

Increase in the number of partner-led counter–IUU fishing operations, particularly in

priority regions and flag states or administrations.

Increase in partner countries’ and authorities’ patrol assets deployed in support of USG-

led operations.

Increase in the number of information sharing agreements with partner countries and

authorities in priority regions.

Increase in the regularity of MCS and other fisheries enforcement training events

conducted in priority regions and with priority flag states or administrations.

Increase in the frequency of joint agency training sessions to strategic partners.

In addition to the above examples of quantitative metrics, we will also develop qualitative

assessment questions such as:

Were USG foreign engagements appropriately focused in priority regions and with

priority flag states or administrations as directed by this Strategy for combating IUU

fishing?

Did the USG, in coordination with INTERPOL and other enforcement bodies, generate

actionable intelligence, information, or analysis that effectively identified vessels, flag

states or administrations, beneficial owners, or criminal organizations engaged in IUU

fishing?

Did the USG disseminate unclassified systems for the sharing of information with top tier

foreign partners or nongovernmental organizations, with built-in collaborative analytic

tools?

Did USG-generated intelligence, information, or analysis effectively support the

identification of vessels, flag states or administrations, beneficial owners, or transnational

criminal organizations engaged in IUU fishing?

Did USG-generated intelligence, information, or analysis effectively support U.S.

investigations against IUU fishing networks or perpetrators?

Did USG-generated intelligence, information, or analysis result in foreign port access

denials levied against IUU fishing networks or perpetrators?

Did the USG improve the capability of partner countries or authorities or entities to

receive and disseminate IUU fishing–related information?

18

Did the USG increase authorities and opportunities to conduct at-sea enforcement

operations in areas where there is no applicable RFMO high seas boarding and inspection

scheme?

Did USG operations and reporting result in meaningful sanctions against IUU fishing

networks and perpetrators?

V. STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE 3: ENSURE ONLY LEGAL,

SUSTAINABLE, AND RESPONSIBLY HARVESTED SEAFOOD ENTERS

TRADE

The seafood sector plays an important role in the U.S. economy, generating approximately 1.5

million jobs and providing a nutritious source of protein to the American public and elsewhere

around the world. Trade in this sector is also vital, as the United States is one of the largest

importers and exporters of seafood in the world. The United States currently imports

approximately 80 percent of the seafood it consumes.

Because the United States is a large seafood-consuming, importing, and fishing nation, we must

take an active role in shaping the conservation and management regimes of fisheries across the

globe. We will continue to work to meet U.S. consumer demand for imported seafood that is

safe, legal, responsibly harvested, and sustainable. IUU fishing undercuts the competitiveness of

the U.S. seafood sectors that operate in some of the most sustainably managed and heavily

regulated fisheries in the world. We address these challenges by engaging other countries and

authorities internationally, both directly and through various multilateral organizations.

Within priority regions and flag states or administrations

1. Continue to assist countries and authorities in working toward adopting and

implementing the PSMA and help implement programs that support robust port state

measures and capacity to prevent IUU fishing products from entering global seafood

markets.

a. Work with and support PSMA Parties through the existing PSMA sub-bodies,

including the Part 6 Working Group, which focuses on and provides funding for

capacity building for PSMA Parties, and the Technical Working Group on

Information Exchange, which will make key information sharing provisions of the

PSMA possible.

b. Support capacity building through trainings conducted by NOAA in partner

countries and authorities to build legal and operational capacity to implement the

PSMA, including with Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, Colombia,

Ecuador, and Peru.

2. Engage with key governments and authorities, industry, and NGOs to develop actions to

improve transparency of seafood supply chains, including implementing new or

strengthening existing traceability schemes and developing related RFMO trade-tracking

19

measures where needed. For traceability schemes, we will promote the use of

standardized, secure, electronic data throughout the seafood supply chain for managing

chain-of-custody, facilitating compliance with legal requirements, and improving

enforcement cases. We will also promote data sharing across traceability schemes and

international databases, including standardization of key data elements that are collected

as a part of these schemes.

3. Work to increase knowledge within governments and industry about U.S. transparency

and traceability standards for imports of seafood and seafood products.

4. Initiate discussions with countries and authorities, bringing in any relevant local or

regional coordination bodies, as well as academia and NGOs, to identify labor abuses and

human trafficking, including forced labor concerns in the fishing industry, and to address

those concerns, including any technical assistance that could be provided.

At the regional and international levels

5. Continue to identify and address poor working conditions and labor abuses.

a. Initiate discussions on labor standards in the seafood supply chain within

international organizations, such as RFMOs and FAO, and, as appropriate,

advance measures to address any identified cases of labor abuses and human

trafficking, including forced labor.

b. Engage the FAO, International Labor Organization (ILO), and the International

Maritime Organization (IMO) Joint Working Group on IUU Fishing, among

others, to promote decent work and advance initiatives to identify and deter

forced labor across each of the three organizations.

6. Facilitate public-private partnerships with civil society, including industry, to support

efforts to prevent labor abuses in the recruitment phases of the seafood supply chain, as

well as efforts to improve data collection and reporting on potential labor abuses aboard

vessels and in seafood processing facilities.

7. Continue to advocate at the World Trade Organization for comprehensive and effective

disciplines that prohibit certain forms of fisheries subsidies that contribute to

overcapacity and overfishing. We will also continue to pursue additional transparency

with respect to the use of forced labor on fishing vessels.

8. Convene seafood traceability workshops for stakeholders, inviting a diverse array of

experts from a range of countries and authorities, to identify pragmatic and tangible ways

to optimize, and coordinate across, traceability schemes and apply the outputs to

traceability schemes within the priority regions.

9. Assess financial flows and the use of financial institutions to launder profits related to

IUU fishing.

20

Use of existing domestic tools

10. Under the Seafood Import Monitoring Program,

9

develop a modernized information-

systems approach to identify shipments most at risk of containing IUU fish and fish

products using predictive analytics, artificial intelligence, machine learning, and cloud

technology.

11. Continue to use existing and future trade agreements (e.g., the U.S.-Panama Trade

Promotion Agreement), including environmental cooperation agreements and work plans

to combat IUU fishing and address forced labor in fishing.

12. Expand and enhance the coordinated use within the USG of Customs and Border

Protection’s (CBP) Commercial Targeting and Analysis Center (CTAC) and Agriculture

and Prepared Products Center of Excellence to take enforcement action at ports that

target IUU fish and fish products; for products that may have improper documentation,

mislabeling, or suspect origins; and conduct trade security operations that prevent

illegally harvested seafood from entering U.S. commerce.

13. Continue the use of intelligence on seafood trade in the priority regions and flag states

generated from the Global Agricultural Information Network (GAIN), U.S. Department

of Agriculture’s (USDA) market intelligence reporting system, and the reports from

USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service officers to stay abreast of developments, as

information becomes available that are relevant to IUU fishing or this Strategy, and

identify responsive actions as needed.

14. Establish additional ad hoc mechanisms, as warranted, to coordinate investigations of the

sources, trade flows, seafood labeling, or advertising/marketing of seafood products with

a high vulnerability to IUU fishing or seafood fraud and refer the results to the

appropriate enforcement agencies, such as NOAA, Coast Guard, CBP, Food and Drug

Administration, or Federal Trade Commission. Such coordination could also include

private entities, as appropriate.

15. CBP, Coast Guard, and NOAA will develop collaborative mechanisms to share timely

information on IUU fishing and its relationship to human trafficking and other illicit

activities, to enhance coordination to address these illicit activities.

16. Collaborate among the members of the IUU Fishing Working Group with the relevant

competences to share timely information on transnational organized illegal activity,

including human trafficking and illegal trade in narcotics and arms that may be tied to

IUU fishing.

Monitoring Benchmarks: To assess progress in ensuring that only legal, sustainable, and

responsibly harvested seafood enters trade, we will evaluate the increase in availability or

implementation of trade monitoring and controls with catch documents or certification programs,

9

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/international/seafood-import-monitoring-program

21

primarily within the priority regions. In addition, steps in developing and coordinating

traceability or catch documentation programs adopted in other key seafood markets (e.g., Japan

and the European Union) could also contribute to progress, as these markets can drive

improvements in the countries and authorities in the priority regions. We will also examine how

international fisheries organizations and other international organizations are contributing at the

global level to improving working conditions and ending labor abuses in the seafood supply

chain. We will select specific metrics for assessing progress in a given priority region or priority

flag state or administration that take into account the unique needs and circumstances within

each, including the variability in the status of seafood trade monitoring frameworks. These

metrics will draw from the following list, which may be augmented by additional metrics

appropriate to a given priority region or priority flag state or administration, some of which may

be informed from the textile, logging, or mining sectors:

Increase in dialogues within priority regions where governments, authorities, industry,

and NGOs can discuss establishing traceability schemes.

Increase in trade monitoring and/or controls with catch documents or certification

programs as well as increased or improved interoperability across multiple programs.

Increase or improvements in implementing PSMA.

Increase in trade monitoring programs with procedures that examine reports of potential

labor abuses aboard vessels and in processing facilities.

Increase in the availability of processes for data collection and reporting on potential

labor abuses aboard vessels and in processing facilities.

Increase in the number of conservation and management measures, programs, or

instruments addressing labor standards in the seafood supply chain adopted by

international organizations, such as RFMOs, FAO, and ILO.

In addition to the above quantitative metrics, we will also develop qualitative assessment

questions, such as:

Did internal USG information sharing and coordination result in preventing the entry of

products that are associated with IUU fishing into the United States?

Did USG-generated intelligence, information, and analysis result in economic sanctions

in the United States (i.e., CBP’s Withhold Release Orders and NOAA seafood import

restrictions)?

Did implementation of U.S. trade agreements bring about progress in achieving this

strategic objective?

VI. CONCLUSION

Through this Strategy, we are reinforcing our efforts to combat IUU fishing so that marine

ecosystems are conserved and the food security, livelihoods, and sustainable development of

communities around the world are supported. Our approach is to focus now on the identified

priority regions and flag states and administrations with an intent to shift to other geographic

regions and flag states or administrations as we build the coalition that works in harmony to

stamp out IUU fishing. The IUU Fishing Working Group will take stock of progress regularly,

22

using the monitoring benchmarks tailored to the assessments of progress in particular areas or

countries and authorities. Such assessments may determine where or how we should adjust a

course of action to achieve the strategic objectives. They may also point to areas for improved

coordination, either across the federal agencies, with other governments and authorities, or with

nongovernmental organizations and the private sector.

Step by step, we will build science-based, intelligence-driven fisheries management with

monitoring, enforcement, and real consequences, incorporating innovative technologies and

increased collaborative international and private sector information sharing. We will make

seafood supply chains transparent and tackle forced labor in the fisheries sector. We recognize

that our task will extend beyond the 5-year period of this Strategy, as we will continue building

real law enforcement and diplomatic consequences for those operating outside of accepted

maritime rules–based order. We are driving toward meaningful progress in isolating those that

engage in IUU fishing and creating an environment where IUU fishing fleets and their owners no

longer benefit economically. In all of our endeavors, we will foster and strengthen partnerships

with other governments and authorities, the nonprofit conservation community, and the private

sector to turn the tide of this global scourge. It is only by working together that we can make

strides in collective and sound fisheries management and maritime governance.

A1 - 1

APPENDIX A: PRIORITY REGIONS

Section 3552 (b) of the Act charges the Maritime SAFE Act Interagency Working Group on

IUU Fishing with developing a list of priority regions at risk for IUU fishing. The work is

intended to help focus and prioritize work through the Department of State’s overseas Missions

to support capacity building, training, and information sharing to combat IUU fishing, as well

as a wide range of activities by all of the Maritime SAFE Act Working Group agencies and the

equities they represent.

The Maritime SAFE Act defines “priority regions” as “at high risk for IUU fishing activity or

the entry of illegally caught seafood into the markets of countries in the region; and in which

countries lack the capacity to fully address the illegal activity.”

The Working Group assessed different regions through a framework that evaluated information

about recent or egregious cases of IUU fishing in each region, the diverse coastal countries’

institutional and operational capacity to deal with IUU fishing, and how the countries within the

region participate in the seafood supply chain and global markets.

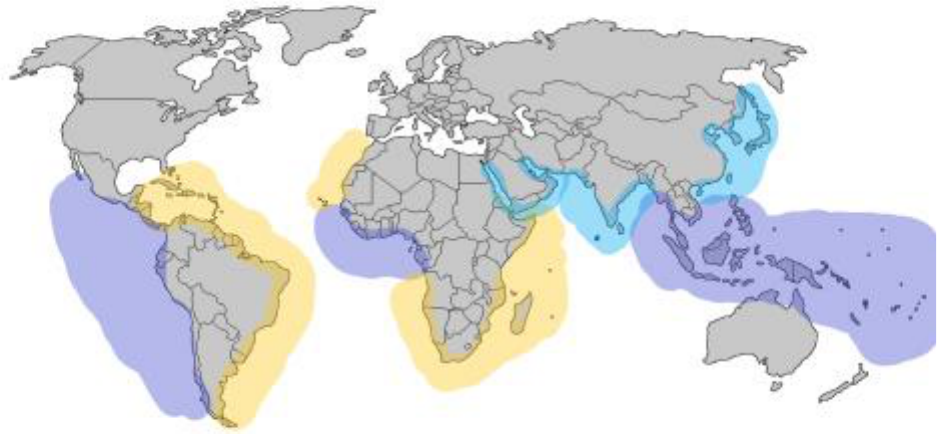

Figure A1. Priority regions categorized into three tiers. Tier 1 priority regions are shown in purple, Tier 2 in

yellow, and Tier 3 in blue.

Based on this analysis, the Working Group developed the following list of priority regions,

along with an illustrative list of the countries, territories, and entities with coastlines in or near

each region, tiered to help prioritize U.S. activities to address the risks of IUU fishing (Figure

A1). Regions are not ranked within each tier.

A1 - 2

Tier One

These are regions where there was both clear information about the challenges resulting from

IUU fishing and ample existing opportunities for U.S. partnerships and activities that could

address those challenges.

South and Central America (Pacific Ocean)

Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico,

Panama, Peru.

Gulf of Guinea

Benin, Cameroon, Cabo Verde, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo, Equatorial

Guinea, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Nigeria, Republic of Congo, São

Tome & Principe, Sierra Leone, Togo.

Southeast Asia (Gulf of Thailand, Java Sea, Banda Sea, Celebes Sea)

Brunei, Burma, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, Philippines,

Singapore, Thailand, Timor Leste, Vietnam.

Pacific Islands

Australia, Cook Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, French Polynesia, Kiribati,

Nauru, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Niue, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Pitcairn Islands,

Republic of the Marshall Islands, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu,

Vanuatu, Wallis and Futuna.

Tier Two

While we had some specific information and known opportunities for cooperative work in the

regions in Tier Two, we could improve our understanding of the situation. U.S. agencies and our

partners are looking for opportunities to build law enforcement cooperation, share information,

and support training and capacity building within these regions.

Central America and Caribbean (Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea)

Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Colombia, Cuba, Costa Rica, Dominica,

Dominican Republic, France (Guadeloupe, Martinique, Saint-Barthélemy, Saint Martin,

French Guiana), Grenada, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Kingdom of the

Netherlands (Aruba, Bonaire, Curaçao, Saba, Sint Eustatius, and Sint Maarten), Mexico,

Nicaragua, Panama, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines,

Trinidad and Tobago, United Kingdom (Cayman Islands, British Virgin Islands, Anguilla,

Montserrat, Turks and Caicos Islands), Venezuela.

South America (Atlantic Ocean)

Argentina, Brazil, French Guiana, Guyana, Suriname, and Uruguay.

Northwest Africa (Atlantic Ocean)

The Gambia, Mauritania, Morocco, Senegal.

Southern and Central Africa (Atlantic and Indian Ocean)

Angola, Madagascar, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa.

East Africa (Indian Ocean)

Comoros Islands, Djibouti, Eritrea, Kenya, Madagascar, Mozambique, Mauritius,

Seychelles, Somalia, Sudan, Tanzania.

A1 - 3

Tier Three

IUU fishing has been raised as a concern in these regions, though details are limited. With this

designation, the Working Group aims to get a better understanding of the IUU fishing problem in

each of these regions.

Middle East and Gulf States (Persian Gulf, Gulf of Oman, Gulf of Aden, Red Sea)

Bahrain, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Oman, Palestinian Territories, Qatar,

Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Yemen.

South Asia (Bay of Bengal)

Bangladesh, India, Maldives, Pakistan, Sri Lanka.

East Asia Pacific (East China Sea, Sea of Japan, Sea of Okhotsk)

China (including Hong Kong and Macau), Japan, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea

(DPRK), Republic of Korea, Russian Federation, Taiwan.

A2 - 1

APPENDIX B: PRIORITY FLAG STATES

Section 3552 (b) of the Maritime Security and Fisheries Enforcement (SAFE) Act charges the

Interagency Working Group on Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing with

developing a list of “priority flag states” to be the focus of U.S. assistance. According to the Act,

a priority flag state’s vessels: “actively engage in, knowingly profit from, or are complicit in IUU

fishing” and, at the same time, the priority flag state “is willing, but lacks the capacity, to

monitor or take effective enforcement action against its fleet.”

The Working Group looked at the countries and authorities within the priority regions it had

previously determined and considered several criteria to understand the full picture of the IUU

fishing problem within those regions better, including:

● Available information about IUU fishing activities by different fleets;

● Authorities’ institutional and operational capacity to monitor and police their fleets and

waters effectively; and

● Willingness to work with the United States to remedy IUU fishing activities by their

vessels.

Based on this analysis, the Working Group selected five priority flag states and authorities to be

the focus of its engagement, assistance, and resources to strengthen efforts against IUU fishing:

Ecuador, Panama, Senegal, Taiwan, and Vietnam (Figure B1).

Figure B1. Priority flag states and administrations overlaid with the tiered priority regions

Each of the five has demonstrated a clear willingness and interest to take effective action against

IUU fishing activities associated with their vessels. Their counter-IUU fishing efforts will be

supported and enhanced by a positive, cooperative partnership with the United States. The

A2 - 2

Working Group will identify diplomatic, military, law enforcement, economic, and capacity-

building tools and provide technical assistance to counter IUU fishing such as:

● Law enforcement training and coordination

● Implementation of the Port State Measures Agreement

● Capacity building, including for investigations and prosecution, developing strong access

agreements, and improving information sharing

● Developing and implementing comprehensive seafood traceability systems

● Promoting and encouraging the mandated use of vessel tracking technologies, such as

vessel monitoring systems

● Negotiating, amending, and/or improving implementation of shiprider agreements

● Engaging in other collaborative international fisheries, maritime security, and marine

conservation initiatives

● Promoting and supporting efforts to combat labor abuses in the seafood sector

FAQs

Q: What are the next steps?

A: The Department of State will develop resources for U.S. missions in priority flag states and

administrations and other countries within the priority regions to support the development of

projects and initiatives to combat IUU fishing. Activities will reflect the IUU fishing concerns

and needs specific to a region or flag state or administration and will take into account U.S.

projects and activities already underway. The United States will engage with the priority flag

states and administrations in the coming months to determine how best to provide support.

Q: What is the difference between the priority regions and priority flag states?

A: While both “priority” designations reflect concerns about a lack of capacity to address IUU

fishing, priority regions are geographic areas where there is a high risk of IUU fishing occurring,

or of illegally caught seafood entering the local and regional markets. Priority flag states or

administrations are those that have issues of IUU fishing occurring with their fleets and have

demonstrated a willingness to address those issues, but may lack capacity. Priority regions

struggle with the problem of IUU fishing from a coastal state and market state perspective, and

priority flag states or administrations struggle with IUU fishing by their flagged vessels. All the

priority flag states or administrations are also located within a priority region; they will benefit

from cooperative activities to prevent and deter IUU fishing in the priority regions’ waters.

Q: Why aren’t all flag states known to engage in IUU fishing included on this list?

A: The Act's criteria call for more than just determining which flag states have vessels that

actively engage in IUU fishing; priority flag states or administrations must have the political will

to address the problem and lack the capacity to do so effectively. As such, some nations that are

also known to have vessels engaging in IUU fishing are not priority flag states in this context

because they have the necessary operational and institutional capacity to prevent and deter these

activities, though they are not effectively using it.

A2 - 3

Q: Will this list be updated or revised (i.e., how long is the “priority” designation valid)?

A: Yes, the list will be updated and revised. The process used to develop this list is an iterative

one; the Task Group will continue to update both the components of the framework used to

determine the priority flag states or administrations and the list itself.

A3-1

APPENDIX C: WORKING GROUP MEMBERSHIP

The Maritime Security and Fisheries Enforcement Act (Maritime SAFE Act) was passed in

December 2019 to provide a whole-of-government approach to counter illegal, unreported and

unregulated (IUU) fishing and related threats to maritime security. Section 3551 of the Act

requires the establishment of a Working Group, consisting of 21 relevant U.S. federal agencies,

to strengthen maritime security and combat IUU fishing.

The 21 U.S. agencies of the Working Group each carry out different activities to confront and

deter impacts and consequences of IUU fishing activities. With today’s interconnected fisheries

and seafood markets, combating IUU fishing requires a coordinated and comprehensive

approach by the U.S. government. The member agencies of the Working Group are: National

Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (current chair until June 2023), U.S. Coast Guard,

Department of State, Department of Defense, United States Navy, United States Agency for

International Development, United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Department of Justice,

Department of the Treasury, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, U.S. Immigration and

Customs Enforcement, Federal Trade Commission, Department of Agriculture, Food and Drug

Administration, Department of Labor, Director of National Intelligence appointee, National

Security Council, Council on Environmental Quality, Office of Management and Budget, Office

of Science and Technology Policy, and the Office of the United States Trade Representative.

The Working Group sets up mechanisms for the agencies to share information, pool their

expertise and efforts, provide technical assistance, and collectively work with governments,

authorities, and the private sector to combat IUU fishing and strengthen maritime security. The

Working Group has currently established four subworking groups to assist in carrying out its

responsibilities: Gulf of Mexico IUU Fishing; Maritime Intelligence Coordination; Labor in the

Seafood Supply Chain, Including Forced Labor; and Public-Private Partnerships. In addition, the

Working Group has convened shorter term task groups to address specific tasks such as the

identification of priority regions and flag states and development of this Strategy.

THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK