THE

BUSINESS

ASSOCIATION

DEVELOPMENT

GUIDEBOOK

A practical

guide

to

building

organizational

capacity

@

US

AID

'-'

.......

oco,..""".

The

EDGE

Project

is

implemen

ted by BearlngPolnt

and

funded

by

USAIO

.

2

THE BUSINESS ASSOCIATION DEVELOPMENT GUIDEBOOK

A Resource for Chambers of Commerce and Business Associations

This electronic guidebook was developed by Mark T. McCord, a Senior Manager for

BearingPoint who has more than twenty years of experience in organizational

management, as a mechanism for Chambers of Commerce and business associations to

have access to international best practices. Through narrative, practical examples and

sample documents, the guidebook provides specific information on critical developmental

areas, as well as addressing the methodology used by high-capacity organizations to

achieve sustainability. EDGE created this resource to assist organizational leaders around

the world in transcending theory in favor of a practical approach to sustainable association

development. It is published due to the support of the United States Agency for

International Development, through the Economic Development and Growth for

Enterprises (EDGE) project in Cyprus.

In addition to the guidebook, this compact disc also contains specific samples of

concepts discussed in the narrative. The samples come from Chambers of Commerce and

business associations around the globe, from both developed economies and those that are

in various stages of development. They are just a few examples of programs, services, and

initiatives that are being implemented successfully by organizations around the world. For

more information about this guidebook or to submit examples for future editions, please

contact:

Mark T. McCord, CCE (Certified Chamber Executive)

Senior Manager, BearingPoint

Chief of Party

Economic Development and Growth for Enterprises (EDGE)

Nicosia, Cyprus

3

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction: The Role of Business Associations in Society

Chapter One: Business Association Development Methodology

Chapter Two: Governance: The Foundation of Sustainability

Chapter Three: Strategic Planning and its Role in Organizational Development

Chapter Four: The Business Association Membership System

Chapter Five: Business Associations and Public Policy Advocacy

Chapter Six: Communications and Marketing for Business Associations

Chapter Seven: Developing Effective Programs and Services

Chapter Eight: Financial Reporting

Chapter Nine: Developing Professional Proposals

Epilogue: Top Ten Ways to Build Organizational Capacity

Examples: Global Examples of Business Association Best Practices

4

INTRODUCTION

THE ROLE OF BUSINESS ASSOCIATIONS IN SOCIETY

SECTION ONE: OVERVIEW OF THE BUSINESS ASSOCIATION’S ROLE

Introduction: Changes in the Business Association Paradigm

Business associations have evolved over thousands of years into organizations that

promote the collective good of their members. The roots of these associations can be

traced to ancient times, when merchants in the Middle East and China joined together to

form cooperatives in order to increase their power in the marketplace. These cooperatives

eventually morphed into merchant guilds that created local monopolies. Eventually, these

guilds gave way to business associations more like those with which we are familiar today.

Modern associations still retain some of the core elements of their forerunners in that they

continue to defend the interests of business and promote economic prosperity. The

evolution of these associations, however, has shaped them into dramatically different

institutions than their predecessors. This evolution has never been more profound than it

has been over the last thirty years, as significant changes have taken place in the structure

and mission of business associations as well as in the services they provide.

With this in mind, the history of business associations as entities promoting

collaborative action is less interesting than the significant changes that have transformed

and continue to transform these organizations into powerful and dynamic engines for

economic growth. New associations are being formed every day, and their relative

strength is measured not by the size of their budgets but by the results they achieve. The

trend in the growth of associations worldwide will continue to rise over the coming years,

which will make the competitive environment even more challenging.

Not so many years ago, success could be measured by the mere existence of

associations. For instance, beginning in the mid-19

th

century, business associations such

as Chambers of Commerce began to proliferate throughout the United States. The

Chambers were widely considered to represent the business community and they served as

the focal point for economic growth and prosperity. Over the years, a paradigm developed

within the Chamber profession as to how the organizations should be managed and what

services they should provide. In some communities, the Chamber of Commerce attempted

to “be all things to all people” by providing a cornucopia of programs and services. It can

be said that these associations took a “shotgun” approach to the business of promoting

business; meaning that they tried to respond to every request of the business community

regardless of need or prioritization. Other Chambers evolved into little more than social

clubs that were run by the elite of the community. Many of these organizations, while

meaning well, initiated programs and services based on factors that had little to do with the

needs of members. Even though membership in the Chamber was voluntary, as they were

developed using the private law model, many of the organizations failed to realize the

importance of marketing their programs and services because, quite simply, there was no

5

competition for members’ money and time.

1

The leaders within a community typically

gravitated to these organizations, but relatively few built strong grassroots support for their

programs and services, as many of the members, while still paying their annual dues, were

detached from the day-to-day operations.

Even so, private law Chambers of Commerce continued to flourish in America

largely due to perceived lack of other options. Because they were not highly regulated by

the state of federal governments, they had maximum flexibility to design and launch

demand-driven programs. The market dictated the success or failure of these programs

that required organizations to remain focused on member needs. In some cases, the

Chambers failed to position themselves to serve the greater business community, which

precipitated the creation of new business organizations that focused on gender, race,

business sector, or geographic area. Since 1980, over hundreds of thousands of business

associations have been created in the United States alone, which generated competition for

the business community’s money and time.

Many private law Chambers use a combination of volunteers and paid staff

members to conduct their programs.

2

This provides for effective implementation of

programs and services, but it also creates a need within the organization to remain vital

through marketing its programs and services. Many of these Chambers have found a niche

in public policy advocacy, using a reform mentality to recruit and retain their membership

base. In the private law system, government cannot regulate the type of programs

associations provide, nor can they “assign” to them tasks that must be implemented.

In Europe, Chambers of Commerce and other business associations have been in

existence for hundreds of years. In most European countries, Chambers of Commerce are

organized according to public law, under which businesses are required to pay annual

dues.

3

It should be said the public law status does not necessarily dictate mandatory

membership, but under the Continental Model, law requires obligatory membership for all

self-employed persons and legal entities that run businesses within a legal district.

4

Obligatory membership includes a regular and mandatory financial contribution to the

Chamber. While this provides stable income to the organization, it also requires Chambers

to fulfill certain tasks defined by law and it sometimes includes supervision of the

organization’s activities by the government.

1

Private Law Chambers are those that exist not through a law passed by government, but rather through

demand of the business community. Membership is voluntary, which requires these associations to provide

programs and services based on member demand in order to remain competitive. The private law model is

most usually referred to as the Anglo Saxon model. For more information, refer to chapter two of this

guidebook.

2

Volunteers in this context are defined as business owners, managers, and/or entrepreneurs that provide their

time free of charge to serve on committees or otherwise assist in the implementation of programs.

3

Public Law Chambers are those that exist under law. Membership is usually mandatory and the

organizations usually serve a geographic area that is set by statute. Many have advisory status, vis-à-vis the

government and are supervised in some form by the government.

4

The Continental Model is a term widely used to define the public law chambers of commerce on the

European continent.

6

Outside of Europe, and especially in developing countries, the public law model

has proliferated. This is especially true in countries that formerly maintained tight control

on all aspects of society. In Latin America, for instance, some governments have

negotiated broad-ranging agreements with unions and business groups that establish

targets for wages, prices and other economic indicators. While these agreements promote

stability within the economy, they at the same time restrict markets from responding to

changing conditions. Under the close scrutiny of the government, many business

associations are reluctant to adopt a reform mentality, even if the business community

supports such a position.

This is not to say that public law organizations are inherently opposed to economic

reforms or are incompatible with a market-based economy. However, their role as agents

for the State must be balanced so as to diminish any anti-reform tendencies they may have.

In Western Europe, and increasingly in other countries as well, balance between State

control of associations and the demand for reform is achieved by the emergence of private,

voluntary-membership associations that represent their members’ interests.

In addition to the Anglo-Saxon (private law) and Continental (public law) models,

there is rapidly emerging a hybrid form of business association that contains certain

elements of each model. Two of these sub-models are the Eurasian and Asian Models.

Most of the organizations utilizing these models embrace voluntary membership but differ

from the traditional Anglo-Saxon model in that they have a law that protects their interests.

Also, they have protection of territory (meaning that no other Chamber or business

association can compete with them in their own region). The Russian Federation Chamber

of Commerce is an example of the Eurasian Model, while the Chamber of Commerce

systems in Indonesia and Japan are examples of the Asian Model.

While organizational models of global business associations tend to vary, one clear

trend has emerged that affects organizations regardless of their geography or governance.

This trend, simply, is one of member demand. Even in countries where public law

Chambers are prevalent, they have come under constant pressure from emerging private

sector associations that are winning the hearts and minds of the business community. It is

as if members in these countries are saying, “You can force us to give you our money, but

you can’t force us to give you our support”. This trend has been prevalent in countries

with private law Chambers for years, but it is now emerging even in transitional countries.

As business communities become more empowered both educationally and economically,

this trend will only increase, putting increasing pressure on aging and outdated

organizations, as well as those that for whatever reason cannot adapt to changing market

conditions.

For years, business executives in transitional countries have regaled the lack of

business association mentality that exists within the business community. While this

complaint makes sense on a tertiary level, in reality it cannot be substantiated, as even in

countries such as Bhutan and Afghanistan, where business associations were virtually

unknown until recent times, the private sector quickly embraced them once it was provided

with a basic understanding of their purpose. It has become obvious that the problem was

7

not within the business community as much as it was within the organizations themselves.

While they struggled to understand their own purpose, the private sector was left twisting

in the wind of change only to eventually anchor itself to the first organization that could

provide significant services.

SECTION TWO: ESTABLISHING A PURPOSE

Many business associations have difficulty because they lack an understanding of

why they exist. Because they don’t understand this basic element of organizational

development, they fail to develop demand-driven programs and thus cannot recruit

members. Organizations that don’t understand their purpose are like rudderless ships that

pound through an angry sea with little sense of direction or accomplishment. This being

said, regardless of a business association’s age or size, it must have a complete

understanding of why it exists. This is the foundation on which success is built.

There is little doubt concerning the importance of business associations to private

sector growth. The question, then, is why are they so important? When analyzing global

organizations, the following factors emerge as the most common reasons why business

associations must exist:

Strong business associations harness the capacity of private businesses.

Owners and managers of private businesses have realized for many years that there

is strength in numbers. Few companies, even those that are considered large by

global standards, can accomplish their goals without the assistance of outside

sources, such as business associations. That’s why companies like Compaq,

Microsoft, and Coca Cola are great supporters of business associations around the

world. They realize that associations provide them the best opportunity to network

with each other and to enhance their economic, social and political interests. The

capacity of small and medium-sized companies is also increased because of the

services that business associations provide, and due to the fact that associations

provide them a collective strength that they do not have on their own. In other

words, the power of “me” becomes the power of “us”.

Strong business associations create business opportunities. One of the major

reasons for the growth of business associations is that they provide business

opportunities for their members. Whether through contacts with companies in a

specific region or around the world, business associations are one of the best

conduits for information and collaboration. This collaboration is a key component

to the development of business opportunities.

Strong business associations protect the interests of both companies and

employees. By harnessing the collective power of their members, business

associations protect the interests of the private sector by developing dialogue with

government. Until recently, many business associations believed that public policy

advocacy (the process of defining issues, developing a position on them, and

advocating this position) was not a service that they could or should provide.

8

However, over the last several years, this attitude has changed as business

associations have come to realize that government simply will not respond to

businesses unless they have an advocate. Business associations are natural

advocates for the private sector, and have learned to use the collective strength of

their members to ensure the views of businesses are heard, and that pro-business

legislation is passed. When this occurs, business associations gain credibility

because they have provided a valuable service to their member companies;

companies benefit because their interests have been protected and pro-business

legislation has been passed; and employees win because stronger companies

provide better job security and more opportunities for advancement. Around the

world, governments are beginning to respond to this approach because they have

come to realize that business pays all the bills, meaning that when businesses

prosper, workers prosper and when workers prosper the government prospers

through increased tax collections, decreased need for social and benevolence

programs, and growing societal harmony. The taxes paid by companies and

workers provide the revenue for government to fund its operations and to provide

assistance for the less fortunate in society. From this standpoint, business really

does pay all the bills, and therefore needs business associations to serve as its

advocate.

Strong business associations promote civil society. For many years, researchers

have sought to develop a link between the strength of business associations and the

development of civil society. The strongest argument in favor of this assertion is

that when business associations provide services to their members, including

encouraging the government to be open and transparent, the framework of civil

society is strengthened. Business associations provide a mechanism in which

legitimate businesses can work together to benefit society.

Strong business associations enhance the business climate. Associations around

the world are embracing public policy advocacy as a way to enhance the business

climate. Movement toward this reform mentality has been largely generated from

member demand for an organization that will protect their interests.

Strong business associations combat corruption: Increasingly, business

associations have become involved in anti-corruption programs, realizing that

corruption costs countries hundreds of millions of dollars while at the same time

eroding competitiveness. The Institute for Private Enterprise and Democracy

Foundation (affiliated with the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Poland)

established a Business Fair Play program that encourages transparency and ethics

in business. Other organizations, such as Confecamaras in Colombia, are battling

corruption in both the public and private sectors through public policy advocacy

campaigns and informational programs.

9

SECTION THREE: FUTURE TRENDS

It has been said that humans can never change the way they act until they change

the way they think. Analysis of business associations over the last twenty years has

proved the applicability of this statement to organizational development as well. In

countries around the world, associations have either progressed or been marginalized

because of their ability to adapt to changing economic, political and social circumstances.

Embracing change is typically not as difficult for young associations, as long as they are

formed because of demand and adopted an appropriate governance structure, but it is

sometimes traumatic for older, more established associations that have spent years either

under State control or mired in an archaic governance process.

Over the past ten years, an effective method has been developed to conduct a

thorough analysis of business associations using an evaluation model based on

international best practices.

5

Through this analysis, it has become apparent that the

emerging paradigm for business association success will focus on the following core

principles:

1. Embracing strategic planning as a value added process. Increasingly,

successful business associations are viewing strategic planning as a necessary value

added commodity to the development process. A strategic plan, which is most

often defined as a three to five year compendium of an organization’s goals and

action steps, is a “roadmap” to achieve specific and measurable results.

Strategic planning typically involves five primary steps. First, comes the

development of a vision statement, which defines the end state that the association

wants to achieve during the planning period. Secondly, it is the development of a

mission statement that briefly outlines the association’s purpose. The third step is

the development of quantifiable goals and objectives in order to determine the

results to be achieved during the time covered in the strategic plan. The fourth step

is the development of action steps to achieve the goals and objectives and the fifth

step is evaluating the results achieved.

Through utilization of a strategic planning mechanism, successful business

associations can achieve significant results within a specific timeframe. It is

essential, of course, that associations gain input from their members prior to the

development of the strategic plan, and it is likewise important for the organizations

to segment the three to five year strategy into one year increments, sometimes

called a “Program of Work”. Some of the most successful business associations in

5

This model, called the Business Association Diagnostic, assesses organizational strength in ten essential

developmental areas. The evaluation, while not a test, does allow for comparison of business associations to

an international best practices model. The diagnostic focuses on 1) mission and objectives; 2) governance;

3) organizational structure; 4) programs and services; 5) organizational staff; 6) financial planning and

reporting; 7) membership development and retention; 8) communication; 9) public policy advocacy and 10)

information management. It was developed by the Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE) and

adapted for use in transitional economies.

10

the world use strategic planning as their first and most important building block for

success. As one association executive in the Czech Republic stated, “It only makes

sense to know where you want to go before you start the trip”. Strategic planning

allows associations to know where they want to go and how they are going to get

there.

2. Changing the membership development paradigm. Few changes in the

business association arena over the last twenty years have been more dramatic than

those in membership development. This is especially true for organizations in

countries that have adopted the private law model, since this usually assumes that

membership is voluntary. Changing demographics and processes have also

affected organizations in countries that favor the public law model, in that private

sector organizations have used new approaches in membership development to

create an important niche within the business community.

Within the last twenty years, the membership paradigm has changed from a

“campaign” mentality to a “process” mentality. Through the mid-1980s, business

association executives in the United States were trained to conduct a membership

campaign every year in order to “recruit” new members. These campaigns, which

typically ranged from a few days to a few weeks, used focused marketing,

testimonials, and other sales tactics to “convince” members to join the

organization. In the late 1980s, organizational executives such as Jerry Bartels,

who at the time was President of the Atlanta, Georgia Chamber of Commerce,

began to view membership in a different way.

6

Over time, other organizational

executives joined the discussion and by the mid-1990s the trend in membership

development for the most aggressive business associations swung toward the

implementation of an overall membership system.

The membership system establishes membership recruitment, retention and non-

dues income generation as a tripartite process for organizational growth. Through

this system, membership is “institutionalized” through the involvement of every

facet within the organization. From the President to the receptionist, membership

development is considered of paramount importance and it becomes everyone’s

“job” to increase the organization’s support. Within this system, membership

retention has the highest priority, while the old paradigm of membership

campaigns is relegated to just one of many processes that may be used to recruit

members. Non dues income, defined as income generated by any source other than

membership fees, is the third element for success, as it generates revenue and

support to augment membership dues.

6

Jerry Bartels was one of the initiators of the “Total Resources” strategy, which focused on membership

retention, recruitment, and non-dues income generation as a way for business associations to obtain the “total

resources” necessary to conduct their operations, programs, and services at one time during the year, versus

using the old paradigm of raising funds all year long. This method is still used by many business

associations today.

11

Business associations around the globe have adopted this system to adapt to

changes in marketplace. Even organizations that have mandatory membership are

using elements of the system to upgrade services and to create more revenue

through non dues sources. This system will provide successful business

associations in the twenty-first century with a mechanism to sustain membership

and financial growth.

3. Establishing transparent financial systems. In transitional countries, where

financial systems even at the highest levels of government have been suspect at

best, business associations have struggled to implement financial processes that are

both transparent and effective. The reasons for this are numerous, but the lack of

adherence to international accounting standards is one of the most obvious. Also,

technological limitations in some countries have made the establishment of such a

system fraught with challenges.

Increasingly, however, donors, association leaders and members have pressured

associations to adhere to international standards as far as financial reporting is

concerned. In response, many associations developed a financial system that

includes the approval of an annual budget, the generation of monthly financial

statements, the allocation of expenses through a general ledger, and the creation of

an income statement to track assets. In addition, many have adopted financial

procedures manuals that outline specific processes that must be used to ensure

financial accountability and transparency. Successful associations rely on

transparent financial practices to instill member confidence and to build credibility

within the business community.

4. Embracing public policy advocacy in support of member demand. Within the

last twenty years, there has been an explosion in the number of business

associations that are involved in public policy advocacy. In fact, after the breakup

of the former Eastern Bloc, a number of emerging associations within Eastern and

Southern Europe made a focus on advocacy a priority item in their strategic plans.

In doing so, they determined, quite rightly, that advocacy is a major reason for

businesses to join associations. On their own, businesses may have little access to

information and little recourse against government regulations, but as part of an

association, they have a collective voice.

As new associations emerged around the world and existing associations made the

transitions necessary to address private sector demands, they benefited from a new

paradigm in public policy advocacy that was developed and promulgated based on

research conducted by a number of organizations. Known as the “advocacy

system” this thirteen-step process institutionalized public policy involvement

within the associations’ strategy. In many countries significant structural changes

in government resulted from the ability of business associations to use this process.

In this century, success in advocacy will no longer be measured by whether or not

an organization is involved, but how successful it is and what process it uses.

12

5. Focusing on economic development as an economic building block. The term

“economic development” has been overused and over analyzed. In its most basic

form, economic development simply means “the creation of wealth”. Any function

that creates wealth develops the economy and increases competitiveness.

It is clear that successful business associations in the twenty-first century will

continue to focus on creating wealth within communities. In January 2002, Juan

Camilo Restrepo, a conservative candidate for President of Columbia, stated,

“Today the name of peace is employment….” In other words, business

associations must play a role in developing the overall economy and providing

jobs.

6. Becoming a broker of information. It has often been said that information is

power. However, it has become apparent that simple access to information does

not create power, but rather the use of this information in promoting economic

growth. Throughout the globe, successful organizations are serving as information

brokers to the business community by compiling, interpreting, distributing and

evaluating data. These organizations will come to understand that information is

not only power, it is also a source of revenue and prestige.

7. Embracing community trusteeship as a core value. Community trusteeship, in

its simplest form, is the safeguarding and/or enhancement of the community for

future generations. Community trusteeship has become a core value within strong

business associations, in that they realize their economic, social and educational

responsibility to future generations. Through trusteeship, these associations have

built grassroots support and credibility to enhance private sector development

through individual initiative.

8. Becoming a driving force in educational and workforce initiatives. According

to Luis Jorge Garay, “Poverty, inequalities of income, ownership and opportunity,

the exclusion of large segments of the population from the benefits of modern life,

amongst other things….The elimination of just some of these would be enough to

achieve true peace”.

7

This statement is becoming increasingly meaningful for

business organizations within transitional and post-conflict countries, but it is also

applicable to those in the developed world. Successful business associations are

heightening their involvement in education and workforce issues as a way to

address social unrest and societal fissures.

9. Celebrating diversity as a way to foster social and political change.

Associations such as the Afghanistan International Chamber of Commerce have set

a standard for diversity that is indicative of successful business associations. In

valuing diversity, business associations can expand their breadth of knowledge as

well as their baseline of support.

10. Using technology to build visibility and grassroots support. Technology or lack

thereof, continues to be a significant factor in business association development.

7

Garay, Luis Jorge. Para donde va Columbia? Bogota. February 1999.

13

While technology offers exponential opportunities, severe gaps in infrastructure in

transitional and post-conflict countries have made this medium inaccessible to

many business associations. Future success will depend on the ability to

communicate with members to gather input and garner support. This means that

technological gaps must be bridged through coordinated assistance from

governments, donors and the private sector. Associations must also harness the

power of technology by investing resources in hardware and software, as well as in

technical assistance for staff members and key volunteers. Currently, for all too

many business associations, the technology super highway is a dirt road.

11. Focusing on marketing strategies to reinforce organizational purpose and

message. It has often been said that “It doesn’t matter what you do if no one

knows you did it”. This is especially true of business associations, which depend

on marketing to increase membership, volunteer support and credibility. Even in

organizations with mandatory membership, marketing of programs and services is

critical to maintain connection with the business community. Future success will

depend on associations’ ability to create, market, and evaluate demand-driven

programs and services, as well as to build an organizational brand that denotes

excellence.

12. Adopting a team-oriented management style. Within the association arena, the

paradigm of management has changed significantly over the last twenty years.

Organizations that operated with a top down management style that limited

empowerment opportunities for staff members have been forced to reassess their

management strategies. A growing number of associations have adopted team

approaches to management, which focus on empowerment and individual

initiative. This paradigm is especially foreign to associations in former totalitarian

countries where hierarchical management was accepted as a cultural norm.

However, even associations with a background in top-down management are

beginning to accept the team approach, as they realize it provides them with

maximum ability to adapt to a changing business climate.

13. Employing and empowering professional staff members. The metamorphosis

of organizations in the West was initiated through a variety of factors, not the least

of which was the acceptance of organizational management as a profession.

Organizations are now harnessing the experience of paid professionals in order to

increase their power and influence. These organizations spend significant

resources on training in order to develop specialists in areas that are important to

their members. It is clear from trends within business associations around the

world that the days of volunteer management are coming to an end.

14. Involving the business community. Even in organizations that possess a highly

trained and profession staff, a significant amount of work is conducted through

volunteers that donate their time to assist in the organizations efforts.

Organizations around the world are beginning to recognize that the involvement of

the business community, first through payment of membership dues and then

14

through involvement in the organization’s programs, is critical to sustained growth.

Again, the concept of volunteerism is foreign to many cultures in that no historical

basis exists for its acceptance as a societal norm. However, in countries such as

Romania, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Russia, volunteers are being

welcomed into associations and they are coming in droves. In fact, volunteerism

within associations is rapidly becoming the rule instead of the exception.

There is no doubt that successful associations are built on a foundation of

knowledge.

However, it is apparent in a changing world that knowledge is not enough to sustain

growth. Rather, it is the use of this knowledge in adapting to change that will create

powerful and sustainable business associations. The remainder of this guidebook will

focus on international best practices in business association management, using examples

from around the world. These examples, while important to an overall understanding of

core organizational management principles will impact associations only if they are used

in combination with strong leadership, vision, and strategy. By changing the way their

leaders think, the paradigm of association management will shift toward more sustainable

organizations and more invigorated business communities.

SECTION FOUR: CONSTRAINTS FACED BY BUSINESS ASSOCIATIONS IN

DEVELOPING/TRANSITIONAL COUNTRIES

Business association development in any part of the world is not easy, as

competition, changing economic structures, and challenging advocacy environments are

forcing even well-established organizations to change the way they conduct business. In

developing and transitioning economies, however, associations face additional constraints

that can be quantified into five basic categories.

The first, and arguably the most complex of these constraints is a lack of a business

association mentality. In many transitional economies, there is a lack of a business

association culture created by the ideology of former governmental regimes. This was the

case throughout most of Eastern Europe, Russia and Central Asia. While virtually every

country in these regions had a history of business associations, most were either controlled

or ended by repressive regimes. When coupled with the transition of most private

enterprises to the State, the years took a toll on the business association mentality and

eventually eroded their ability to be effective. The associations that did survive tended to

be tightly controlled by the State, with most serving as public relations conduits for the

government’s economic policies. Once these regimes changed, the countries were left

with a large number of state owned enterprises, a lack of understanding concerning the

market economy, and relatively little enthusiasm for the support of business associations.

The latter stemmed largely from the belief that associations either could not provide

demand-driven programs and services or that they were merely extensions of government

as had been the norm in many of these countries for over 40 years.

This lack of understanding of the need for business associations created a second

constraint, which was lack of trust. In many transitional countries, oppressive regimes had

15

eroded trust in institutions as a whole. Since many existing organizations, usually national

Chambers of Commerce, had been used by governments to promote specific economic and

social policies, the business community was slow to put their trust in them. This was

especially true since the leadership of a number of these organizations did not change.

With the same people in control and government in transition, little trust could be

developed between the existing associations and the private sector. This eventually led to

either the creation of new demand-driven business associations or the reform of the

existing institutions. The former was perceived to be the path of least resistance in many

countries, as the existing institutions were considered to have too much “baggage” to be

effective even with new leadership. Romania typified many transitional countries by

proliferating new business associations while at the same time undertaking reform of the

Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Romania and Bucharest (CCIRB). CCIRB is

today a growing and progressive organization that is meeting the needs of Romania’s

private sector.

The proliferation of new associations, combined with the restructuring of existing

ones led to a third constraint, which was lack of communication between organizations and

their members. The first hurdle for associations to clear was to create a need within the

private sector to become members. This was a daunting task that many organizations had

not mastered even ten years removed from the change in government. Of course, success

in this endeavor was based on an organization’s ability to develop demand driven

programs and services, while at the same time marketing the benefits of association

membership to the private sector. Associations that were able to develop an effective

communications strategy, such as the Brno Chamber of Commerce in the Czech Republic,

benefited through membership growth. Those that could not communicate effectively

either remained as small and low-capacity organizations or focused on a different method

of achieving sustainability, such as mandatory membership. The latter alleviated the need

for the associations to communicate effectively, while still providing them with a

consistent source of income.

Eventually, though a large number of associations created communications and

marketing strategies in order to reach their potential members. The most successful of

these strategies focused on the matching of customized benefits and services to the needs

of specific members. For instance, manufacturing companies have different needs than

retail trading firms, so the programs and services offered to them should also be different.

Many organizations also created communications products such as newsletters, magazines,

advocacy reports and websites. These products not only provided a variety of ways for

them to market their activities, but they also allowed the organizations to collect member

input and data.

In addition to dealing with external communication issues, a majority of the

associations also dealt with imperfect internal systems that caused chaos within the

management structure. Once internal communications broke down, the associations were

unable to establish a consistent message for the private sector. Over time a number of

these associations were able to improve their internal communications systems by

instituting weekly staff meetings, networking events, and modern management techniques.

16

Lack of effective internal communication led to an overall inability to adjust to a

management style that is conducive to peak organizational effectiveness. This fourth

constraint was exacerbated by the ideology and/or culture within the transitioning

countries. Many had been governed by oppressive regimes for decades, causing a

generation of managers to adopt a top-down management style. This higherarchical style

created bureaucracy and was not compatible with the ability of associations to meet market

demand. This being the case, association leaders had to change their own management

paradigms to adapt to new circumstances. This process moved painfully slow in many

developing nations, and even today the higherarchical management style is prevalent in a

number of transitional countries. Organizations such as the Dhaka, Bangladesh Chamber

of Commerce and Industry have instituted new participatory management systems, though,

which are becoming the more prevalent in transitional countries. DCCI not only

empowers its employees to perform at peak efficiency, but also keeps past volunteer

leaders involved in an advisory council to assist the president and board of directors in

addressing important private sector issues.

A fifth constraint faced by associations in transitional economies was either lack of

a legal infrastructure or the adherence to an archaic law(s) that governed organizational

development. Many countries in transition had laws on the books that specifically

acknowledged one or more business associations (usually a national Chamber of

Commerce or industrialists organization) as the government’s “official” representative on

economic issues. Few of these laws were repealed quickly, which left new business

associations in a kind of legal limbo, which led to a lack of legitimacy for most demand-

driven organizations. When coupled with the lack of a legal framework for doing

business, this led to the proliferation of scores of business associations that lacked

credibility with the government and had little legitimacy within the private sector.

Eventually, a majority of transitional countries repealed their archaic business association

and/or non-governmental organization laws, but some were replaced with new laws that

put different types of restrictions on the development of business associations. There is

still much debate within transitional countries as to the legal framework within which

organizations should operate.

In many transitional countries, non-existent or inconsistent legal frameworks led to

government’s lack of interest in acknowledging the right of associations to advocate on

behalf of their members. While some governments simply ignored the associations, others

actively pursued a “containment policy” whereby one association or group of associations

would be allowed access, while the others remained on the fringe of the policy debate.

After several years of focused attention from private sector organizations, governments in

many transitional countries are becoming more inclusive and supportive of a wide variety

of institutions.

Many of the constraints noted above are being favorably addressed by aggressive

and forward-looking business associations. The most successful organizations are

focusing on making a business case for membership and are ensuring participation from

businesses of all sizes. By tailoring programs and services to companies of different sizes

17

and types, associations in transitional countries have been able to create significant return

on investment for their members, which of course has led to increased member support.

While difficulties remain, these associations are examples for their counterparts around the

world.

18

CHAPTER ONE

THE BUILDING BLOCK METHODOLOGY: DEVELOPING HIGH CAPACITY

ORANIZATIONS

The key to building the capacity of business associations is an understanding of the

developmental model that allows for the creation of sustainable organizations.

BearingPoint has used the following model extensively to build the capacity of Chambers

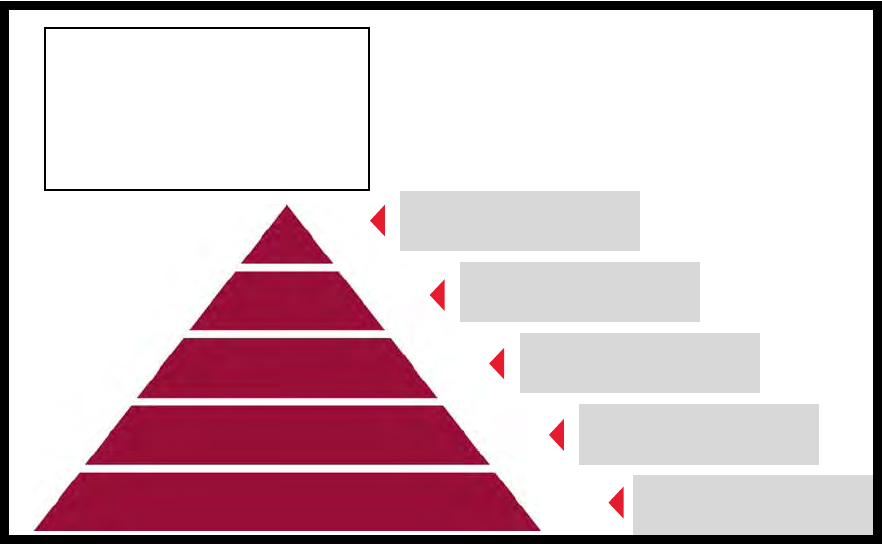

of Commerce and business associations around the globe. The pyramid in Figure 1.1

outlines the model’s major components, which are:

Governance: Organizational strength flows from the development of a fair and

transparent governance system. This is the foundation on which capacity is built.

Programs and Services: Capacity is also built through the development and

implementation of demand-driven programs and services that meet the private

sector’s needs. Membership input is critical in order for these programs and

services to be truly demand-driven, which typically necessitates an ongoing series

of surveys, focus groups and communication in order to assess member attitudes.

Visibility: Visibility is often confused with effectiveness. However, there are

multitudes of associations around the world that are visible but not effective. The

danger in transitional and post-conflict countries is that donor support will

artificially create visibility that cannot be sustained by the organization due to its

overall lack of capacity. True visibility, which leads to credibility and ultimately to

sustainability, is built on a foundation of good governance and progressive

programs/services that promote member involvement. Visible organizations are

ones that tell their story effectively, utilizing both media and word-of-mouth to

create awareness.

Credibility: It may take a number of years for a business association to build

credibility with its members, the community and the government, as this only

happens through sustained focus on governance, programs/services and

communications.

Sustainability: Credibility over a number of years establishes a sustainable

organization. Sustainability must not be considered only in economic terms, but

also including other factors that contribute to overall organizational health, such as

effective leadership. A sustainable organization is one that has power, both with its

members and with stakeholders in government and the private sector.

It should be noted that these levels are not mutually exclusive, meaning that one

has to accomplish one before moving on to the other. In fact, it is common for business

associations to work on governance, programs/services and visibility at the same time.

However, it is important that an association not “skip a level”. For instance, it would be

counter productive to focus on programs/services and visibility and ignore governance.

19

Figure 1.1 The Organizational Sustainability Pyramid

Movement up the sustainability pyramid requires customized intervention within

the following four activity areas. Each one of these areas should contain demand-driven

and practical objectives and activities that focus on building organizational capacity:

1. Foundational Resources: These are resources that assist business associations in

developing strong and transparent governance structures based on international

best practices. Some of these resources include effective bylaws, election

procedures, strategic planning processes and ethical guidelines. (Governance)

2. Informational Resources: These are resources that provide ongoing, customized

information to business association leaders in order to build their knowledge and

effectiveness. Some of these resources include technical assistance, publications

and networking. (Governance/Programs and Services)

3. Developmental Resources: These are resources that actually build capacity within

business associations by establishing programs and services and internal

management capacity. Some of these resources include staff development and

mentorship. (Programs and Services/Visibility)

4. Financial Resources: These are resources that business associations need to sustain

their operations as well as to manage growth. In transitional countries, this may

require short-term financial assistance through temporary external financing in

order to establish a firm financial foundation. (Credibility/Sustainability)

T

h

Credibility

Sustainability

Visibility

Programs

/

Services

Governance

Must be powerful

Must be believable

Must be noticed

Must be strategic and

demand-driven

Must be transparent

The

Sustainability

P

y

ramid

20

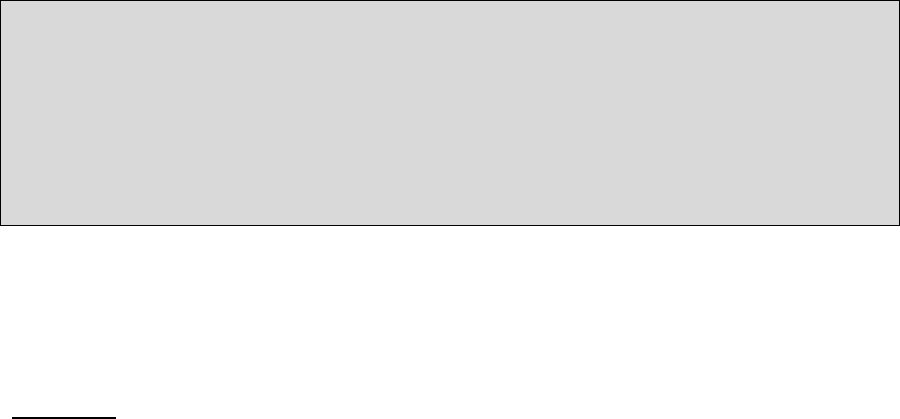

As an association moves toward sustainability, it is buoyed by increased

membership support, which leads to empowerment. The higher an organization moves up

the sustainability pyramid, the higher its members will move up the empowerment

pyramid shown below in Figure 1.2. Those members at the pinnacle of the pyramid, who

are considered to be committed and empowered, are virtual “customers for life”, meaning

that it would take an almost apocalyptical situation to erode their support for the

organization. This being the case, the higher the percentage of members that are in these

two categories, the more sustainable an association becomes. The empowerment pyramid

is shown below, and outlines the process required to turn an “uninformed” businessperson

into an “empowered” member. Graduation of members from “uninformed” to

“empowered” is directly proportional to the organization’s success in moving up the

sustainability pyramid described earlier. The more an association moves toward

sustainability, the more its members will be committed to its success.

Figure 1.2 The Membership Empowerment Pyramid

These pyramids operate parallel to each other, meaning that as an organization

creates a transparent governance structure, institutes demand-driven programs, and

becomes more visible, the business community responds by increasing its monetary and

emotional support, until becoming “empowered”. Reaching the “empowerment” level

essentially means becoming a “customer for life”. At this level, members have so much of

themselves invested in the organization that they would not leave except under virtually

apocalyptic circumstances. While a majority of members in any organization, regardless

of where it is in the world, never reach the “empowered” level, a strong, sustainable

Committed

Empowered

Involved

Interested

Uninformed

E

m

Value representation and

sustain it.

Believe in representation and

are willing to support it.

Acknowledge representation

and become part of it.

Acknowledge representation

but don’t know how it works.

Want representation but

don’t know how to get it.

The

Empowerment

Pyramid

21

organization will strive to ensure that a large majority of its members are at least at the

“committed” level.

The relationship between these two pyramids is at the core of organizational

success, as they show the relationship between strategic governance, programming, and

communications to member involvement. It should be noted that increased funding is not

specifically mentioned in the sustainability pyramid, though it is assumed that a

sustainable organization will also be one that has a funding level that is appropriate to

conduct it operations, communications, and programming. The reason it is not a specific

part of the pyramid is that as members move up the pyramid, and especially when they get

to the “committed” and “empowered” tiers, they are willing to support the organization

with their finances as well as their time. This being the case, there is a corollary between

“empowered” members and a financially “sustainable” organization.

22

CHAPTER TWO

GOVERNANCE: THE FOUNDATION OF SUSTAINABILITY

“The problem with business association governance is that everyone wants to ride

the roller coaster, but few want to design or fix it”. There is a great deal of truth to this

statement in that it is exhilarating to ride a roller coaster….the ups and downs of the trip

are exciting and at the same time somewhat frightening. Yet, at the end of the ride, one

feels excited, even refreshed, by the experience. Those who design or repair roller

coasters enjoy none of the thrill of the ride, but are arguably the most important people in

the process as they keep the train from jumping the tracks. The establishment of good

governance within a business association does the same thing….it keeps the organization

from losing direction, getting off-course, and eventually “jumping the track” into chaos.

For business associations in a growing number of countries, governance has

become more than just a step in the organizational process. It has become one of the most

important aspects of building organizational capacity. In fact, according to the

sustainability pyramid discussed in the last chapter, governance is the foundation on which

the entire organization is built. It is virtually impossible to build a strong association on a

weak foundation, so focus on governance is of critical importance to business associations.

Definition of Governance

In order to discuss governance, it first must be defined. For purposes of this

guidebook, governance is defined as “the development of transparent and fair governing

structures that adhere to international best practices”. “Transparent” is defined as “a

governance structure that is supported by policies and procedures created with the

involvement of organizational members and that are communicated to these members in a

way that ensures understanding and accountability”. Transparency comes when everyone

within the organization has input into the governance structure, understands it, and is

accountable for it. In a transparent organization, everyone from the President down to the

smallest member firms understands the governance structure and is held accountable for

their actions regarding it.

Increasingly, business associations around the world are gravitating toward a

governance system based on international best practices. When evaluating some of the

world’s most successful organizations, one finds common elements within their

governance structures that provide a model for associations in transitional countries.

These structures can be consolidated into three primary categories: legal, organizational

and accountability.

Legal structures are those that are established by law and/or by internal governance

procedures. In many countries, Chambers of Commerce and business associations are

governed by one or more laws that outline the scope of their authority and activities. In

others, associations are governed primarily by market forces that determine their success

23

or failure. Typically, business associations fall into one of three broad models, two of

which establish organizations under public law. They are known as the State, Anglo-

Saxon and Continental models. The following text box contains a brief explanation of

each model:

Figure 2.1 Global Business Association Models

State Model (Public Law): The state model is one where the Chamber of Commerce is controlled either

directly or de-facto by the central government (public sector). Funding typically comes from mandatory

membership or a quasi-mandatory system that provides the Chamber of Commerce with guaranteed income.

While these organizations are typically well funded, most are ineffective representatives of the private sector.

In addition, most do not undertake advocacy activities as they are controlled in whole or in part by

government interests. Countries using the State Model include Libya, China, Vietnam, Iran, and Saudi

Arabia. Its strengths are that it provides stability, sufficient financial resources, little or no competition, and

legal protection from competition. Its weaknesses are that it provides little or no incentive to advocate for

private sector interests and miniscule motivation to provide services. Also, the organization may not be

viewed as professional but rather a government agency and be governed by individuals that may not

necessarily be advocates for the private sector but rather party officials put in place by government leaders.

Anglo-Saxon Model (Private Law): The Anglo-Saxon model is prevalent in the United States, Great Britain,

India and other constitutional democracies. Membership in these associations is voluntary and income is

generated both from membership dues and non-dues income in the form of events, publications, and

services. Many of these Chambers of Commerce have strong advocacy programs to support the interests of

the business community. Countries using the Anglo-Saxon Model include the United States, United

Kingdom, Australia, Argentina, South Africa, and Chile. The model’s strengths are that competition requires

these organizations to provide top-notch programs and services, voluntary membership ensures a focus on

private sector initiatives, they are usually led by professional staff members that are trained in organizational

management, they typically serve as strong advocates for the private sector, and are typically managed by a

board of directors consisting of private businessmen and women.

Continental Model (Public Law): The Continental model is prevalent in Western Europe and parts of

Central and Eastern Africa (in countries that were former colonies of Western European powers). These

Chambers of Commerce usually have mandatory membership and thus have little incentive to launch

sweeping advocacy initiatives. Most of the Chambers operate under the principle of “social responsibility”,

which essentially means their focus is more on employee’s rights than those of employers. Countries using

this model include Germany, France, United Arab Emirates, Portugal, Austria and Turkey. Major strengths

of this model include guaranteed funding through mandatory membership, negligible competition, and

legislative protection. The major weaknesses of this model are that organizations may have little or no

incentive to meet member needs, lack of focus on volunteerism and professional staff, and programs/services

that are not based on member demand. Also, they may be considered advocates for government policy

instead of private sector initiatives.

Those organizations that are established by law under either the State or

Continental models are usually empowered with a specific mission, scope of activities and

structure that is defined within sections of the law. There are instances where more than

one law governs the establishment and operation of business associations. This is an

anomaly, however, as most countries have no more than one law that governs the

establishment and operation of business associations, or at the most two….one for the

Chamber of Commerce system and another for other business organizations including

trade associations. An increasing number of countries are consolidating archaic business

association legislation into singular laws that provide the basis for activities by either

chambers of commerce or business associations. Pakistan’s business association law is

24

included in the appendix as an example of one that unifies all applicable legislation under

one representative law.

As in Pakistan’s legislation, several areas are typically addressed within laws that

govern business associations. Typically, these areas fall into the following broad

categories:

Figure 2.2 Major Functional Areas of Laws Governing Business Associations

Legal Framework: Business association laws typically outline the legal parameters under which an

association or group of associations can operate. This may include registration procedures as well as legal

authority to represent the private sector within and outside the country.

Scope of Responsibilities: Business association laws also typically outline the scope of responsibilities that

organizations have relative to the government and the international community. Some national chambers of

commerce, for instance, are authorized by law to “officially” represent a country’s private sector in

international economic forums, trade exhibitions and trade missions.

Membership: In most but not all cases, laws governing business associations establish mandatory or quasi-

mandatory membership. Mandatory membership requires that all registered businesses (in the case of a

chamber of commerce) or all those within a sector (in the case of a trade association) become members of the

organization. In some cases, this is enforced by providing the chamber of commerce or sectoral association

with the right to license, certify or oversee the standards of registered businesses. In other cases, the

organizations are not provided this right and therefore have no enforcement authority if companies do not

join as required by law.

Organizational Structure: Laws governing business associations usually establish a required structure under

which the organizations must operate. This is most common in cases where the law established a federation

model (such as in Pakistan). In some cases, the law acts almost in the capacity of organizational bylaws as it

outlines specific governance practices to which the organization(s) must adhere.

Programs and Activities: It is typical for laws governing business associations to establish at least a partial

list of programs and services that the organizations should or may provide. In many cases, the government

may even “outsource” services such as business licensing, issuance of certificates of origin, and export

certification to an organization(s) as a way to provide them with consistent revenue. In other cases, the law

provides only broad categories under which programs and services should be constructed.

Relationship to Government: It is also common for these laws to establish guidelines under which an

association(s) may interact with government. Some, especially those under the State Model, are restrictive

and provide few opportunities for business associations to advocate for the interests of the business

community. Others provide ample opportunities for public-private dialogue.

Dissolution: Over the last ten years, it has become popular for laws to address the dissolution of assets

should an organization(s) cease to operate. This is especially the case in countries where Chambers of

Commerce own property and other assets that would require liquidation should the organization cease to

function.

In recent years, there has been a clear trend away from the establishment of

business associations under public law, meaning that more and more organizations are

changing to a voluntary membership system that is driven by market forces versus legal

authority. Countries such as Poland, Hungary and Zambia terminated mandatory

membership in favor of a voluntary, market-oriented approach to development. It is clear,

however, that business associations can thrive under either the public law or private law

systems if they institute sound, transparent governance systems that allow for a focus on

private sector needs.

Organizational structures focus on how an association is organized internally.

This is usually identified on an organizational chart similar to the one contained in the

25

chart below, which outlines the organization of the Bethlehem Chamber of Commerce

(Palestine):

Figure 2.3 Bethlehem, Palestine Chamber of Commerce and Industry Organizational Chart

This chart establishes the members (General Assembly) as the organization’s focal

point and provides it the authority to elect a board of directors in the number and

qualifications established in the bylaws. It also provides the board of directors with

authority to elect a chairman of the board (chief non-paid executive) as well as to hire a

managing director (chief paid executive) that reports to the Chairman and ultimately to the

board as a whole. The managing director is responsible for overseeing the implementation

of the organization’s programs and services through the departments established beneath

his/her authority. In other words, the managing director is a paid, professional

organizational executive that is responsible for the association’s day-to-day operation

including personnel, materials, financial reporting and membership services. He/she is

empowered, according to this organizational chart, to employ professional staff members

to manage each department under his/her authority. The managing director employs an

executive secretary that reports directly to him/her but has no oversight authority relative

to the rest of the staff.

It is not uncommon for business associations to have counselors that provide input

into their strategy and activities. For instance, the Jerusalem Chamber of Commerce has a

legal counselor as well as an economic advisor to provide input into issues that may be

outside the expertise of the organization’s board of directors and staff. In addition, many

26

business associations have affiliate or federated organizations with which they either

interact or are obligated to acknowledge. The Jerusalem Chamber of Commerce is aligned

with a group of four or more organizations that have no oversight authority but do

represent partners with which the Chamber collaborates.

For associations that are organized under a federation, the following model from

the Palestinian Chamber of Commerce provides an overview of an organizational structure

that contains many elements of international best practices:

Figure 2.4 Overview of Federation Organizational Structure

General Assembly:

The general assembly compromises all elected directors of the constituent chambers. It comprises 109

businessmen freely elected by their respective business communities representing collectively all economic

activities of the Palestinian business community. The elected boards of each chamber internally elect a

chairman who automatically becomes a member of the federation council.

Federation Council:

The elected chairmen of the constituent chambers form the Federation Council, which internally elects the

Federation’s president and three vice presidents, one from Gaza and two from the West Bank. The Chairman

of the Jerusalem Chamber of Commerce was elected by consensus as President of the Federation Council.

The following officers were also elected: Chairman of the Gaza Chamber as a first vice president, Chairman

of the Hebron Chamber as a vice president, Chairman of the Nablus Chamber as a vice president, Chairman

of the Ramallah Chamber as treasurer and chairman of the Bethlehem Chamber as a vice treasurer. The rest

of the elected Chamber chairmen are members of the Federation Council.

The Federation Council’s main task is to create harmony and synergy between the constituent Chambers, to

unify the business community behind issues of economic importance, and to provide ongoing capacity

building support for its members. The Council has a regular rotating monthly meeting at the constituent

chambers. The president of the Federation may call for emergency sessions upon his or any member’s

request in order to address any urgent issues that may arise.

Secretariat General:

General Assembly

(

Member Association’s Boards

)

Federation Council

(

Elected b

y

Federation Members

)

Secretariat

(

Chief Paid Executive/Mana

g

ement Staff

)

Administrative (Operational) Directorate

Directorate of Economic Affairs

27

The Federation President nominates a Secretary General, but the appointment has to be approved by the

Council. This also applies to the Secretary General’s assistant. The Secretary General is responsible for the

Federation’s day-to-day operation. He is also responsible for implementing the Council’s policies.

Operational Directorates:

The Federation’s structure in terms of operational staff is not completed. Currently, only ten staff members

are working for the Federation. This includes the Secretary General and his assistant along with two

secretaries, a chief economist, a senior researcher, two junior researchers and two information technology

specialists.

Directorate of Economic Affairs

The Directorate of Economic Affairs serves as the Federation’s backbone and has a staff of five headed by a

senior researcher. In the future, the plan is to strengthen this directorate to have two main departments;

private sector strategies/policies department and department of services & technical assistance. The private

sector strategies/polices department will consist of three subordinate units; research & studies, foreign trade

and credit & investment. These units will be vertically integrated into the department of strategies and

policies to advocate for better involvement of the private sector in legislation, trade agreements and

economic development initiatives. Additionally, it will be horizontally integrated into the business advisory

& consultation services in order to promote capacity building, marketing & trade promotion and access to

credit and the provision of business development services.

Delivery of these services will be done by the Federation at the constituent chamber level. The main task of

these Federation units is to coordinate activities among the chambers, initiate the process of learning from

success stories, and institutionalize international best practices within constituent organizations.

While there are certainly other organizational models that are appropriate, the two

noted above are common (with variations) for use by local and national business

associations as well as federations. Regardless of the ultimate design, the important

elements of an organizational structure are:

1. The establishment of members as the ultimate governing authority. In both of

these examples, the organizations’ membership elected the governing boards and

thus had input into the overall structure.

2. The establishment of a pro-active governing board. The board of director’s size is

not as important as the criterion established to elect organizational leaders, but

international best practices dictate that boards function at a higher level when

containing no more than 21 members. Board members should be visionary leaders

that are committed to the organization’s success and are willing to act in a

constructive, transparent, and collective manner.

3. The establishment of transparency as organizational culture. The organizational

structure must be supported by transparent bylaws and other regulations that

establish election procedures, ethical behavior, and constructive member input.

4. The employment and empowerment of paid staff: In both of these examples, paid

staff form the critical nexus between the governing board, which is responsible for

strategy, and the members, which expect effective, demand-driven services.

Regardless of their location on the organizational chart, the employment of

professional, highly-motivated staff members is critical to organizational success.

28

An association’s organizational structure is critical in its overall development, as

structural difficulties in the area of governance are often the cause of problems in other

areas such as membership, programming and communications. For this reason,

organizations should take full advantage of international best practices models such as

those outlined above.

Accountability structures focus on the establishment of internal regulations that

promote accountable behavior on behalf of members, staff, directors and other leaders.

This structure includes but is not limited to the following:

Figure 2.5 Accountability Structures Utilized by Progressive Business Associations

Bylaws: Bylaws establish the framework under which an organization exists. It outlines the structure,

operational procedures, and other governance principles under which the organization operates. Bylaws are

considered by most highly-functioning organizations to be their most important governance document. Two

sample bylaws are included in the appendix and provide an overview of the types of information contained

therein.

Codes of Ethics: As an increasing number of business associations focus on transparency, codes of ethics

have become widely used in order to ensure accountability among members, directors and staff. Codes of

ethics usually contain language that addresses conflict of interest, director and staff ethics, gifts, and

guidelines for interaction with public officials among others. A sample code of ethics from the Afghanistan

International Chamber of Commerce is included in the appendix. In AICC’s case, every staff member and

elected director (from the Chairman on down) signed the code of ethics and was bound by its accountability

structure.

Personnel, Policy and Procedures Manual: As organizations grow, operational guidelines become

increasingly important, which is why a number of organizations have created personnel, policy and