0

OCTOBER 16, 2012

Annual Report of the

CFPB Student Loan

Ombudsman

1

Table of Contents

Executive Summary....................................................................................... 2

About this Report .......................................................................................... 3

Annual Report of the CFPB Student Loan Ombudsman ............................ 4

Introduction ........................................................................................... 4

Part One: Issues Faced by Student Loan Borrowers ............................ 5

Part Two: Ombudsman’s Discussion .................................................. 13

Part Three: Recommendations ........................................................... 18

Appendix ............................................................................................. 21

Contact Information..................................................................................... 22

2

Executive Summary

In the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, Congress

established an ombudsman for private student loans within the Consumer Financial

Protection Bureau. In its first year of operation, the CFPB entered into a memorandum of

understanding with the Department of Education to coordinate on student loan

complaints, began accepting student loan complaints at ConsumerFinance.gov in March

2012, and released a number of consumer education tools to assist borrowers.

Outstanding student loan debt is now over $1 trillion, with private student loans

accounting for more than $150 billion. There are at least $8 billion of private student

loans in default, representing more than 850,000 individual loans. Private student loans

are issued by banks and credit unions, state-affiliated and non-profit agencies, schools, and

other financial companies. Like in the mortgage market, creditors often employ third-

party servicers to collect payments from private student loan borrowers. Many of these

servicers are also active in the federal student loan market.

In less than seven months, the CFPB has handled approximately 2,900 private student

loan complaints. For complaints where companies report monetary relief, the median

amount of relief reported was $1,572. The vast majority of the complaints were related to

loan servicing and loan modification issues.

Eighty-seven percent of all student loan complaints were directed at just seven companies.

This is not surprising, given that the private student lending and servicing markets are

highly concentrated.

The complaints and input received by the CFPB resemble many of the same issues

experienced by mortgage borrowers, such as improper application of payments,

untimeliness in error resolution, and inability to contact appropriate personnel in times of

hardship. Many borrowers feel overburdened by paperwork and other requirements to

activate incentives marketed prior to loan origination.

Similar to the mortgage market, active-duty servicemembers and their families sometimes

experience difficulty exercising their rights under the Servicemembers Civil Relief Act.

Like mortgage borrowers, student loan borrowers face challenges when attempting to

refinance or modify their debt. Many borrowers are unable to take advantage of low

interest rates due to a lack of refinance options, while others have been unable to secure

modified payment plans during the difficult labor market environment.

3

About this Report

October 2012

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act established an ombudsman

within the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Pursuant to the Act, the ombudsman shall

prepare an annual report and make appropriate recommendations to the Secretary of the

Treasury, the Director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the Secretary of Education,

and Congress. This report is the first annual report meeting the requirement set forth in the Act.

Rohit Chopra

Student Loan Ombudsman

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau

4

Introduction

Student loans have now surpassed credit cards as the largest source of unsecured consumer

debt.

1

Before the financial crisis, the private student loan market boomed, and many consumers

borrowed significantly to pay for postsecondary education expenses. This report offers analysis,

commentary, and recommendations to address issues reported by consumers in the student loan

marketplace.

Unlike federal student loans, borrowers seeking assistance with private student loans needed to

identify an appropriate state or federal regulatory agency that had oversight over a specific lender

or servicer. In the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, Congress

established a student loan ombudsman within the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau to

assist borrowers with private student loan complaints. This function is now fully operational.

Last year, the CFPB entered into a memorandum of understanding with the Department of

Education to coordinate and share information on student loan complaints. In March, the

CFPB began accepting student loan complaints, allowing consumers to log onto the secure

“consumer portal” on the CFPB’s website or to call a toll-free number in order to file a

complaint, receive status updates, provide additional information and review company responses.

Since March, the CFPB received approximately 2,900 complaints about private student loans.

TABLE 1: PRIVATE STUDENT LOAN COMPLAINT SUMMARY STATISTICS

The CFPB also launched a suite of consumer tools for student loan borrowers, which tens of

thousands of consumers have used.

2

These tools provide borrowers with information on how to

identify a payment plan, determine what loans they have, and get out of default.

1

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and Department of Education, Report to Congress on Private Student Loans (July

2012).

2

Available at www.consumerfinance.gov/students

Complaints received March 2012 to September 2012 2,857

Median age of consumer filing complaint (of those with disclosed age) 29

Highest amount of relief (as reported by company) $83,671.59

Median amount of relief (as reported by company) $1,572

Note: Highest and median amounts of relief reported by company are based on those cases for which a company

reports relief.

5

Part One: Issues Faced by Student Loan

Borrowers

Sources of Information

To identify the range of issues faced by borrowers with their student loans, the report relies

primarily on the complaints the CFPB has received. In addition to this information, we reviewed

other sources of data, such as the comments submitted by the public in response to the CFPB’s

request for information on private student loans,

3

submissions to the “Tell Your Story” feature

on the CFPB’s website, input from town halls and discussions with consumers, and comments

submitted by organizations that receive complaints on student loans in response to a request for

information on private student loan complaint data.

4

Limitations

The report does not attempt to present a statistically significant picture of issues faced by

borrowers. It is, by design, not a random sample and not intended to communicate the

frequency to which certain practices exist. While the market information we receive from

consumers, schools, and industry yields a broad range of input, readers should recognize the

inherent limitations of the underlying data. However, the information provided by borrowers

can help to illustrate where there is a mismatch between borrower expectations and actual service

delivered. Representatives from industry and borrower assistance organizations will likely find

the inventory of borrower issues helpful in further understanding the diversity of customer

experience in the market.

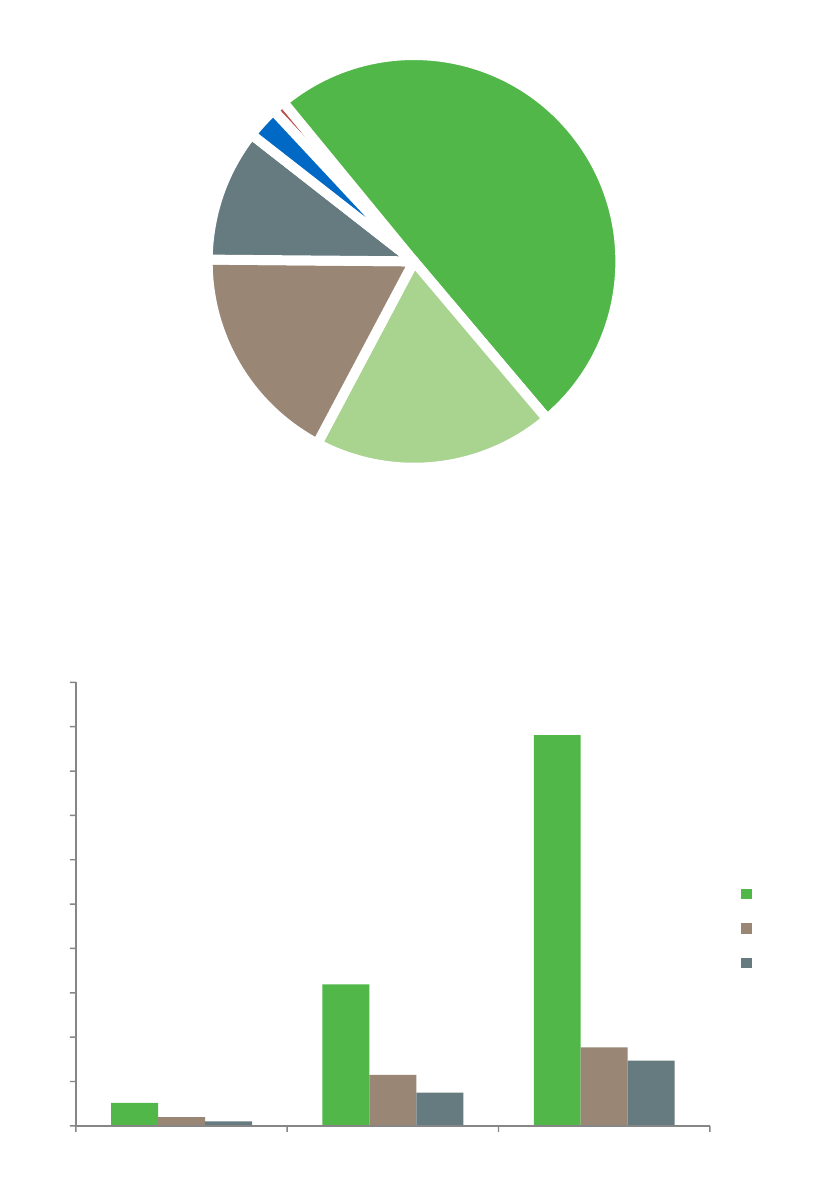

TABLE 2: PRIVATE STUDENT LOAN COMPLAINTS BY COMPANY

MARCH 2012 – SEPTEMBER 2012

3

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Request for Information Regarding Private Education Loans and Private Educational

Lenders, Docket ID CFPB-2011-0037, Federal Register (November 17, 2011).

4

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Request for Information Regarding Complaints From Private Education Loan Borrowers,

Docket ID CFPB-2012-0024, Federal Register (June 14, 2012).

Company % N

Sallie Mae 46% 1145

American Education Services (PHEAA) 12% 296

Citibank 8% 198

Wells Fargo 7% 176

JPMorgan Chase 5% 123

ACS Education Services 5% 116

KeyBank 4% 90

Others 13% 329

Total 100% 2473

Note: This chart comprises complaints that have been matched to a company on the CFPB’s “company portal.” For

commentary on the distribution of complaints by company, see part two of this report.

6

Issue Highlights

Borrowers overwhelmingly report issues that relate to the servicing of their loans.

TABLE 3: PRIVATE STUDENT LOAN COMPLAINTS BY ISSUE TYPE

MARCH 2012 – SEPTEMBER 2012

Below, we describe some of the types of issues that borrowers face, along with some illustrative

examples:

5

Responsible Borrowers Stymied

Inability to speak with personnel empowered to negotiate a repayment plan. By far, the

most common concern communicated by borrowers has been the difficulty negotiating a

repayment plan with their servicer in periods of unemployment, underemployment, or financial

hardship. Many borrowers report frustration that they are unable to identify appropriate

personnel that can make a determination about their repayment options.

Inability to refinance. Many student loan borrowers have a limited credit history when applying

for a private student loan— and their interest rate reflects a high level of risk. But as borrowers

build a credit profile, graduate, and earn income, they are often unable to refinance existing

student debt at a lower rate— in stark contrast to the market for mortgage refinance products.

We have heard from borrowers who say they are looking for loans with more attractive terms,

but many have been unable to take advantage of today’s historically low rates.

We heard from a borrower who reported that he had $40,000 in private student loans and large

monthly payments, reflecting the high interest rates for his loans. He reported that his credit

profile is “leaps and bounds” better than when the borrower applied for these loans.

Nevertheless, he said that his servicer informed him that they do not offer any opportunity to

refinance and urged him to seek alternative financing elsewhere in the marketplace. But the

borrower reported that alternative financing was not readily available.

5

Some parts of this discussion may reference a specific complaint submitted to the CFPB. In these cases, the

consumer provided consent to include some details of their complaint. In other cases, this discussion may reference

other input, such as comments submitted by the public in response to the CFPB’s request for information on private

student loans.

Issue %

Getting a loan

(Confusing terms, rate, denial, confusing advertising or marketing, sales tactics

or pressure, financial aid services, recruiting)

5%

Repaying your loan

(Fees, billing, deferment, forbearance, fraud, credit reporting)

65%

Problems when you are unable to pay

(Default, debt collection, bankruptcy)

30%

Total 100%

7

Inability to access repayment plans previously advertised. Many private student loan

borrowers are able to enroll in alternative repayment arrangements included in the terms and

conditions of their loans. However, some borrowers note that enrolling in a new repayment

arrangement is a difficult process. Some servicing personnel may not be fully aware of all

policies or incentive plans available to private student loan borrowers.

We heard from one borrower who reported that he made full payments each month for six

years. He said that his loan was transferred from one servicer to another. According to the

borrower, when he informed his new servicer that he wished to enroll in an alternative payment

plan available under the terms of his loan he was informed by his new servicer that his original

payment option was not available through the new servicing platform and that he could not be

enrolled.

“Good faith” partial payments leading to default. When borrowers are unable to negotiate a

new repayment plan, many make “good faith” payments for less than the full payment amount.

Many borrowers report that they send their servicers checks for what they can afford each

month, including letters explaining their situation. In some cases, borrowers note that they send

in more than 50 percent of their take-home income. However, these payments still resulted in

delinquency and default on their private student loans. Some borrowers worry that, after

defaulting because of inability to make full, monthly payments, their defaulted loans will become

due in-full—presenting an even larger obstacle. Some borrowers express frustration that servicer

personnel encourage them to pay what they can afford without informing them that they will still

be on a path toward default.

Servicing Surprises

Bankruptcy-triggered defaults. Included, but perhaps not well understood, in the terms and

conditions of some private student loan contracts are provisions that put a loan in default when

borrowers file for bankruptcy.

We heard from one borrower who reported that he was paying his loan as agreed, but normal

billing statements suddenly stopped. He later learned that because a parent filed for bankruptcy

after a recent divorce, the loan was put in default because the parent was a co-signer. He stated

that he is unable to get clear information about his options to fix the situation. He expressed

concern that his credit report is now badly damaged, despite being a responsible borrower.

Another consumer sought to restructure his other debts through bankruptcy in order to free up

cash to make student loan payments. The consumer never sought to restructure his student loan

debt. But after the bankruptcy filing, the private student loan servicer placed the loan in default,

and it was subsequently sent to a debt collector.

Unexpected checking account transactions. In some cases, borrowers have deposit accounts

with the same financial institution that handles their private student loan. If the borrower has not

paid his scheduled student loan payments in full, the lender might deduct funds from the

borrower’s checking account.

Consolidation in the banking industry and changes in ownership of private student loans may

mean that borrowers are unaware that the owner of their loans and their checking account

provider are part of the same financial institution. In these cases, a checking account offset can

catch borrowers unaware, leading to overdraft fees in addition to the surprise transaction.

Handling of payments. We heard from borrowers who were concerned about how their

payments were applied to their accounts. Some expressed frustration that they were unable to

8

reach the appropriate staff member with their servicer in order to correct a mistake in how a

payment was applied to their account.

One borrower described issues with a loan he thought he had paid off many years ago; however,

his servicer sent him a statement that may not have reflected an accurate payoff balance. He said

that he received no additional communication from his servicer until years later, when he was

informed that he owed a small remaining sum in principal and accrued interest on that amount,

on an account he believed to be closed.

Another borrower reported that she made her payment on-time and in full each month. She

described experiencing problems with payment application and timing and being charged

unexpected fees. She stated, “I am set up for automatic payment through the lender’s site and I

still incur late fees.”

Confusion when loans and servicing rights are bought and sold. Many student loan

borrowers have found that their loans have been sold or their servicer has changed. Some of

these borrowers report experiencing lost paperwork and changes in terms.

One borrower reported that she took out a loan in 2003 with a large commercial bank and that,

in 2010, her loan was sold to another lender. One day, she stopped receiving paper statements

entirely. In the absence of monthly statements, she has had to call to confirm her payment

amount each month. She has experienced payment processing delays and has been charged late

fees several times since her loan was sold.

Crediting of overpayments. Over the course of multiple terms or years, many borrowers take

out multiple student loans with different terms and conditions.

If multiple loans are held by the same servicer and borrowers attempt to repay more than the

minimum monthly payment, according to borrowers, their excess funds are sometimes applied in

two unusual methods: the servicer may apply the excess payment to future minimum payments

rather than paying down principal. Borrowers have cited the task of constantly having to ask to

apply the excess payments to the principal as taxing, as they believe servicers should

automatically do that. Another method cited by a borrower is the application of excess payments

to the principal of the loans with the lowest interest rate rather than to those with the highest.

Limited access to account information. Borrowers indicate that they may not be able to

easily obtain access to their full student loan payment history. After requesting an amortization

schedule, some borrowers explain that they have difficulty obtaining a full payment history with

a clear explanation of how payments have been applied to interest and principal. Some

borrowers also note that website functionality to retrieve this information is unhelpful.

Conflicting instructions. Some borrowers have described that different employees of the

same servicer give conflicting answers to questions about their loans. In some cases, the

information may not match information provided on consumer-facing websites.

Difficulty enrolling in incentives. It is common for lenders to offer various incentives to

borrowers in marketing materials prior to origination. These might include interest rate or

principal reductions for engaging in activities that increase the likelihood of repayment, such as

degree completion or enrollment in an auto-debit program.

We have seen in complaints and heard directly from borrowers that they are confronted with

hurdles to activate these incentives. We heard from one borrower who described how a servicer

did not process her auto-debit incentive enrollment paperwork because it was submitted “too

early.”

9

We heard from another borrower who had signed up for automatic payments upon entering

repayment. She had 36 consecutive monthly payments debited from her checking account.

After her 36

th

payment, she applied to have her co-signer released from her loan—a benefit that

was advertised at the time she took out the loan. Her lender denied her application, stating that

some payments debited from her account were “late,” and did not comply with the terms of her

co-signer release benefit. She told CFPB that her lender said “it could take up to three days for

the payments to post and some of them posted late.”

Barriers to co-signer release. Some private student loan originators describe that co-signers

can be released from responsibility after a period of consecutive on-time payments. However,

this release is not automatic. Some borrowers describe that it is difficult to activate this option,

which often requires additional credit checks.

Payment processing timelines. Borrowers report that some servicers take multiple days to

post submitted payments and sometimes charge borrowers interest on outstanding principal

during the processing period. Some servicers take between two and four days to process a

payment submitted online, without a retroactive posting date from the time the funds were

debited from the borrower’s account. Some borrowers complain that this processing delay is

atypical relative to the procedures used by servicers for other financial products.

Loss of benefits due to servicer personnel-suggested action. Many private student loans

offer incentives to borrowers to encourage on-time monthly payments. These include interest

rate reductions for a fixed number of on-time payments, interest rate reductions for the use of

auto-debit and co-signer release after a set number of on-time monthly payments. Changing

payment plans sometimes revokes eligibility for benefits otherwise available to borrowers under

the terms of their loans.

We heard from multiple borrowers who applied to have their co-signers released from their

private student loans, following the remittance of a set number of consecutive, on-time monthly

payments. These borrowers’ loan terms stipulate that co-signer release is only available for

borrowers who make their first series of consecutive payments on-time. These borrowers filed

complaints claiming that their servicers informed them that they were ineligible for co-signer

release because they enrolled in interest-only repayment plans—options they selected at the

suggestion of servicer employees two years prior. These borrowers report that, at the time, they

were not informed that this decision would cause them to forfeit their co-signer release benefit.

Frustration Faced by Struggling Borrowers

Debt collection practices. Many borrowers in default voice concerns about certain tactics

employed by private student loan debt collectors. According to some borrowers, private student

loan debt collectors may attempt to exploit borrowers’ confusion between the collection tools

available to recover private loans and the extraordinary powers granted to federal student loan

debt collectors. For example, borrowers report that debt collectors have claimed the authority to

garnish wages without a court order, seize Social Security checks, and offset tax refunds. These

tactics may make borrowers more likely to remit a payment on a loan in default.

We heard from a delinquent borrower who was told that if he signed up for $250 monthly,

automatic payments, he would be able to avoid default. After beginning these payments, he was

contacted and informed that his loan had been charged-off—his balance of almost $50,000 was

due immediately, in full. He described his payment arrangement, but was told “it doesn’t

matter.”

10

Death of primary borrower. Some borrowers describe that the process for handling a loan

when the primary borrower dies is not always clear. The death of the primary borrower may

trigger a default, accelerating the balance due and leaving a co-signer, often the parent or

grandparent of the deceased borrower, legally responsible for payment. However, much like

with federal student loans, some private student lenders allow co-signers to apply to have the

outstanding debt cancelled. Co-signers complain that information about discharge or alternative

arrangements in the case of death of the primary borrower is not readily available and that

decisions are made on a case-by-case basis, giving co-signers little understanding of how the

process works or if they will be successful.

We heard from family members of deceased borrowers who had been contacted by debt

collectors seeking to recover private student loan debt. When families inquired about loan

cancellation or other arrangements, some were unable to obtain answers either by phone or by

sending written requests directly to debt collectors.

Disability issues. In contrast to federal student loans, some borrowers who have become

totally and permanently disabled subsequent to entering repayment may be unable to have their

private student loans forgiven. Some borrowers did not realize this difference between private

and federal student loans existed.

We heard from a borrower who said that his private student lender informed him that disability

discharge was unavailable. The borrower is suffering from kidney failure and has no income

other than his disability checks. He is unable to afford his monthly payments and has no choice

but to default on his loan. The difference between federal and private student loans in periods

of disability was not well-understood.

Off-hour collection calls and do-not-contact notices. Some borrowers report receiving

collection calls late in the evening or early in the morning, outside of the ordinary window for

permissible calls as specified by applicable laws.

Borrowers report attempting to request a third-party debt collector cease collection calls, only to

have the written request, sometimes submitted by certified mail, unprocessed by the collector.

6

Accuracy of credit reports. Typically after navigating a special circumstance of loan repayment,

such as bringing a defaulted loan current, borrowers complain that there is a lag or lack of

resolution to an inaccurate credit report filed by the servicer or debt collector.

We heard from a borrower who described that she requested forbearance by phone, only to

discover months later that the request was never processed and that a 90-day past-due balance

had appeared on her credit report. After contacting her servicer, the borrower paid off the past-

due balance on her loan and successfully placed the loan in forbearance. Ninety days later, a

second past-due balance appeared on her credit report. After contacting her servicer again, she

discovered that she was provided with an incorrect loan balance and the negative credit notation

reflected unpaid interest.

Forbearance fees. Some lenders and servicers charge a fee for forbearance. The borrowers

who request forbearance on their loans are typically those who cannot afford to make their

payments. Correspondingly, a monthly charge for forbearance forces borrowers to come up with

money as they attempt to demonstrate that they are experiencing financial hardship.

6

The Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (FDCPA) requires third-party debt collectors to cease attempts to collect a

debt by phone if notified in writing by a borrower to halt collection calls. This does not change the borrowers’

obligation to repay, but guarantees that the borrower will no longer receive collection calls.

11

We heard from borrowers who believe that paying a fee to have their servicer temporarily

alleviate them from making payments is in conflict with the underlying purpose of the

forbearance—these borrowers feel that there are not realistic policies in place to assist borrowers

when they are financially troubled.

Challenges Faced by Military Families

Barriers to accessing SCRA rate cap. Many borrowers entering active-duty service have

reported obstacles to obtaining their interest rate cap afforded by the Servicemembers Civil

Relief Act (SCRA). These obstacles may include unclear instructions, lost paperwork and

conflicting information about the status of their accounts and terms of their loans.

We heard from a borrower who reported that he has been attempting to obtain his SCRA rate

cap for four years—receiving potentially incorrect and conflicting information from his private

student loan servicer. According to the borrower, his servicer has also declined to provide him

with a payment history that reflects the retroactive application of the rate cap to the start of his

active-duty military service, a requirement under the SCRA.

Errors when processing the SCRA rate cap. Many borrowers have multiple loans with

different lenders and servicers, disbursed at different times and possibly at different rates. One

borrower with several loans stated that the interest rate on one of the loans was increased up to

the rate cap, when instead the rate cap should have no impact on the loan because it was already

less than six percent.

Difficulty determining whether the SCRA rate cap was retroactively credited. For pre-

service obligations, a servicemember should generally receive the six percent rate cap applied

starting from the date they entered active-duty service. Borrowers have told us that they cannot

easily determine whether the rate cap was applied at the appropriate date, since they do not

receive a detailed statement about any overpayments they may have made and how these

overpayments were credited to the account.

Barriers to retaining the SCRA rate cap. Once a servicemember receives an interest rate cap

under the SCRA, this benefit is guaranteed for the duration of his or her active-duty military

service. However, servicemembers may be asked by their servicers to submit additional

documentation in order to retain this benefit as they continue to serve on active-duty, rather than

making use of other means to verify their service status.

Other Concerns

For-profit college affiliated loans. Many borrowers filing complaints and providing input to

the CFPB obtained loans to attend for-profit colleges. Some consumers described how school

representatives provided information on loan programs in order for the borrower to quickly

obtain financing for enrollment. Some borrowers report that they have been unable to find

adequate employment in order to service the debt offered by parties affiliated with the school,

despite assurances to the contrary.

Overall confusion between private and federal student loans. Some borrowers note directly

that they were never advised on the difference between a federal and private student loan. This

issue has arisen for borrowers at both the origination and repayment stages of their loans. Once

in repayment, many private student loan borrowers ask for a form of Income-Based Repayment,

a program only available for federal student loans.

12

While lenders do provide the terms of agreement in promissory notes, including associated

benefits and protections, many borrowers state they were unaware of the categorical differences

between federal and private protections.

13

Part Two: Ombudsman’s Discussion

Based on the issues and themes described in Part One, the ombudsman offers commentary

relevant to various market participants. This discussion represents the ombudsman’s

independent judgment and does not necessarily represent the view of the Consumer Financial

Protection Bureau.

----------------------

In March, the CFPB began accepting student loan complaints. The CFPB has been able to

facilitate handling of student loan complaints asserting servicer or lender errors, as well as

provide guidance through various interactive web tools about how borrowers can responsibly

manage debt. The CFPB worked with private student lenders and servicers, as well as the

Department of Education, to which the CFPB directs a substantial volume of consumers.

It is critically important to articulate that the summary of issues is not intended to measure the

prevalence of certain practices. Furthermore, this first annual report likely includes complaints

about problems borrowers faced well before the establishment of the CFPB, but these

borrowers did not have a clear place to seek assistance. In all likelihood, many of the borrowers

filing complaints have loans originated prior to the use of special disclosures for private student

loans with underwriting standards far different than those used today.

Complaints filed by consumers range in complexity. Consumers might file a simple inquiry in

the system when they doubt the quality of the information they receive from the lender or

servicer call center representative, while others provide details of serious issues they have been

unable to resolve.

Generally speaking, the distribution of complaints by company is not surprising given our

estimates of relative market shares. The company that received the most complaints was Sallie

Mae, which operates large platforms engaged in origination, servicing, and collections. The

number of complaints per company does not seem particularly disproportionate to their number

of loans.

But while the complaints and input to the CFPB are not and should not be interpreted as a

representative sample, the insights from these data do raise concerns. Specifically, the breadth of

potential servicing errors and the inability to easily modify a loan bear an uncomfortable

resemblance to experiences faced by homeowners in the mortgage market.

Some of the deficiencies identified in the mortgage servicing industry might also exist in

student loan servicing. Mortgage borrowers have complained, among other things, about

inappropriate application of payments, timeliness in error resolution, and inability to contact

appropriate personnel when facing economic hardship. Many of these complaints are strikingly

similar to the input provided by and complaints received from student loan borrowers.

In particular, some of the issues raised by borrowers related to processing of payments and

paperwork could be caused by issues with information technology systems and operational

processes that have the potential to impact many more borrowers beyond those filing

complaints.

Improper foreclosure can cause major harm to a consumer, as can an avoidable default on a

student loan. Recent experience in the mortgage market is a clear reminder that low quality

servicing practices for large consumer credit markets can harm both consumers and the

economy more broadly.

14

Borrowers also noted difficulty enrolling in alternative repayment options, incentives, and other

benefits that were advertised prior to origination. Many lenders publicly adopted a Code of

Conduct requiring them to take reasonable steps to assure that borrower benefits be preserved

even if a loan is sold or servicing is transferred. Others entered consent decrees with the

Attorney General of New York. If these benefits were included in contractual loan terms but

not honored by the lender or the lender’s representative, this response may raise legal concerns.

It is important to note that consumers do not actively choose their student loan servicers. The

servicer’s customer is generally the lender or the owner of the loans. Given this structure, it is

difficult for borrowers to exert market discipline that ensures appropriate customer service.

Student loan borrowers cannot easily modify or refinance their debt. Many of the

complaints the CFPB receives come from consumers who borrowed private student loans just

before the financial crisis. A substantial portion of these loans might have been directly

marketed to students without the benefit of counseling from the school, potentially with rates

and terms far less favorable than those available for federal student loans.

Some consumers expressed regret about their borrowing decisions, and many report that they

actively explored ways to reduce their payments. Many borrowers are employed, but are paying

rates with large margins over the index rate. Like the concerns heard by responsible

homeowners today, many student loan borrowers and their families are frustrated at their

inability to take advantage of their improved credit profile and today’s low rates. It is worth

noting that this concern was communicated by borrowers with all types of student loans.

Many consumers with private student loans accrued debt prior to the recession, but graduated

afterward. The difficult labor market has led many to be unable to make their payments. A

common theme found in the data is the difficulty that borrowers face when seeking to obtain

clear and accurate information regarding alternate payment plans. Those who were able to

secure a response from their servicer were generally unsuccessful in securing a modification,

except for a short-term forbearance period.

Few borrowers were seeking to have their loans forgiven when facing hardship— most seem to

be searching for a clear answer on whether options might exist, but struggled to get an answer

from their lender or servicer.

If these loans remain in distress without the opportunity to modify or restructure, the level of

default and distress in the student loan market might further compromise many young adults

from full economic participation.

Lenders

The consequences of default are painful, particularly for a young consumer. The CFPB would

welcome creative efforts by lenders to help borrowers restructure their debt prior to or after

default. While there may be limitations and challenges, such as legacy IT systems, the need for

clarity on accounting treatment of novel repayment plans (for portfolio lenders), and restrictions

of bond documents and rating agencies (for lenders funded in the capital markets), it is unlikely

that these challenges are insurmountable.

The CFPB believes that lenders can identify and execute successful loan modification strategies

that are beneficial to the consumer and lead to higher overall collections. While these programs

might not be able to reach every distressed borrower, there may be opportunities to pursue in

the short-term for a substantial segment of borrowers.

15

Other Industry Participants

Many industry participants have remarked that borrowers are not well-informed about the

features and options of their loans, even if they receive extensive documentation and paperwork.

The desire of several incumbents to reduce customer confusion and restore customer trust is

admirable, and there are many short-term opportunities to actualize this goal.

First, existing market participants might consider updating their commonly-used terminology.

Based on the data analyzed for this report, some of the confusion experienced by borrowers may

be related to the usage by private student lenders of terminology more commonly associated

with federal student loans, as well as the inconsistent definitions of similar terms used by various

private student lenders and servicers.

For example, the most common student loan by number of consumers borrowing each year is

the Subsidized Stafford Loan.

7

Incumbents may have customers who hold both federally-

guaranteed subsidized loans, as well as private student loans. However, terms like “deferment,”

“grace period,” and “forbearance” have different meanings for each of these products.

Incumbent private student lenders and servicers may be able to reduce confusion by modifying

this federal student loan terminology and potentially developing new terms in order to increase

clarity when there are meaningful differences between loan types.

Another idea raised by some industry participants is to leverage existing technology to replace

excessive paperwork burden placed on borrowers when activating various loan incentives. For

example, a servicer might require the completion of a paper application to activate the immediate

interest rate reduction incentive for auto-debit, which may not process for two billing cycles.

This is surprising to many observers, since it is common practice for online servicing platforms

to allow electronic funds to transfer from a bank account in a very short period of time. As with

other issues identified above, there may be modest changes to systems and settings or relatively

simple process improvements that could benefit a large number of borrowers.

The CFPB has heard from consumers describing that they were required to submit

documentation (such as transcripts and diplomas) to apply their graduation incentive to their

loan. However, there are existing data sharing systems already in place between schools, lenders,

and servicers that identify whether a student has completed the degree program.

Some consumers interpret this excess paperwork as an obstacle employed by incumbents to

reduce adoption of rate reductions. Process improvement and reduction of burdensome

requirements for borrowers to activate incentives might aid in correcting this perception.

Many incumbent market participants have noted that the majority of complaints they receive are

initially filed with the CFPB. However, private student lenders, servicers, and collectors might

consider emulating federal student loan program guidelines that require disclosure of instructions

on filing a complaint with an ombudsman.

Continued dialogue with the CFPB and incumbent market participants to identify short-term and

long-term opportunities to enhance servicing quality might prove to be beneficial.

8

Proactive

attention to these emerging issues might mitigate the need for additional regulatory attention.

7

Also known as a Direct Subsidized Loan.

8

The CFPB’s Office of Installment & Liquidity Lending and Office for Students plan to convene these discussions in

upcoming months. Please consult the contact information at the end of the report to seek further information.

16

Investors and Entrepreneurs

Since opening last year, the CFPB has heard from investors and entrepreneurs eager to explore

opportunities in the student loan market. Interest from these parties is very encouraging, since

the market would benefit from greater competition and innovation.

The largest actors in the market operate businesses largely designed for the discontinued Federal

Family Educational Loan Program. These participants leveraged a school-based marketing

infrastructure to market private student loans, as well. But this school-based model need not be

the primary use of private financing for higher education.

Investors and entrepreneurs evaluating the private student lending market might find that private

lending might reach larger volumes at more attractive risk-adjusted returns when targeted to

employed college graduates seeking to refinance student loans. Should this business model

prove viable, there could be substantial benefits to consumers, who could refinance out of loans

with high rates or poor servicing once they have secured stable employment. Given the potential

for significant scale in this business beyond today’s origination volume, borrowers might be able

to choose products that still retain certain federal student loan benefits. Of course, to the extent

that borrowers are refinancing federal student loans, borrowers should be aware if they are

ceding any protections or giving up a fixed interest rate for a more risky variable rate. The CFPB

looks forward to continued engagement with market participants exploring these opportunities.

Community Banks and Credit Unions

A number of leaders from small financial institutions have expressed interest in developing long-

term relationships with young customers but note that many of them are unable to enter the

mortgage market due to their student loans. One way that small financial institutions might

assist younger customers to get closer to homeownership is to offer products that allow them to

refinance any student loans they might have with rates in excess of their perceived repayment

risk. Small financial institutions might even be able to assist customers worried about falling

behind on student loans by offering products that might allow them to be successful.

The CFPB received very few complaints from borrowers with private student loans from small

financial institutions. Increased participation by small financial institutions might benefit the

market.

Institutions of Higher Education and Assistance Providers

Colleges and universities have an opportunity to promote successful debt management strategies

for students and recent graduates. Financial aid professionals might conduct analyses to identify

student segments at risk of financial distress. For example, students borrowing substantial

amounts of private student loans would be well-served by individual counseling, potentially with

third parties, on how to enroll in alternative payment programs to comfortably service their debt.

School alumni associations might also have a role to play in management of student debt.

Recent graduates might value options for refinancing student loan debt, and alumni associations

might identify appropriate mechanisms to facilitate the offering of these options.

Legal assistance and counseling organizations have increased their service offerings to assist

struggling student loan borrowers. In fact, many of these organizations have referred consumers

to our online consumer tools and to our complaint system. The CFPB welcomes additional

17

community, religious, and charitable organizations to make use of our offerings to provide

greater assistance to student loan borrowers.

9

It will also be important for military service organizations, veterans service organizations, and

members of the Judge Advocate General Corps to pay particular attention to military families

with student loan debt. It appears that active-duty servicemembers are not always provided with

clear information about their rights under the Servicemembers Civil Relief Act, which provides

for a six percent rate cap applicable to both federal and private student loans accrued prior to

active-duty service.

10

The CFPB’s Office for Students and Office of Servicemember Affairs will

conduct training sessions and provide additional information for service organizations to assist

military families.

9

Organizations wishing to receive periodic information on tools and resources for struggling borrowers can subscribe

to updates at ConsumerFinance.gov.

10

Servicemembers and their families can learn more about their benefits under the SCRA by visiting Ask CFPB and

the Student Debt Repayment Assistant at ConsumerFinance.gov.

18

Part Three: Recommendations

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act requires the ombudsman to

make appropriate recommendations to the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban

Affairs, the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, the House

Committee on Financial Services, the House Committee on Education and the Workforce, the

Secretary of the Treasury, the Director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and the

Secretary of Education.

----------------------

Recommendations for the Senate Committee on Banking,

Housing, and Urban Affairs, the Senate Committee on Health,

Education, Labor, and Pensions, the House Committee on

Financial Services, and the House Committee on Education and

the Workforce

Identify opportunities to spur the availability of loan modification and refinance

options for student loan borrowers

The inability to modify or lock in lower rates might impede student loan borrowers from

participating in more economically productive endeavors, such as household formation or small

business creation. In its most recent report to Congress, the Treasury Department’s Office of

Financial Research acknowledged that conditions in the student loan market could “significantly

depress demand for mortgage credit and dampen consumption.”

With 40 percent of households headed by an individual under 35 having student loan debt,

11

the

economy may already be feeling some of the effects. Census data reveals that 6 million

Americans ages 25-34 lived with their parents in 2011, a sharp increase from just a few years

ago.

12

The National Association of Realtors estimates that people aged 25-34 made up 27

percent of all home buyers in 2011, the lowest share in the past decade.

13

Like with mortgages, many borrowers with private and federal student loans have been unable to

take advantage of today’s historically low interest environment. While these borrowers may not

be in financial distress, they may be paying interest rates that are not commensurate with their

risk profile.

Input provided to the CFPB reveals that many recent graduates are seeking to pay less in interest

on private and federal student loans, so they can one day purchase a home or otherwise

economically progress. Many entrepreneurs and small financial institutions are eager to serve

these borrowers, and these market entrants could provide needed innovation and competition to

a concentrated market. However, they may face capital constraints or other impediments to

offer refinance products. Addressing these impediments to refinance options may prove to be

valuable not just for individual borrowers, but for the housing market and the broader economy.

Federal student loan borrowers have options for emerging from financial distress that private

student loan borrowers generally do not. If a borrower’s private student loan was sold or

11

Survey of Consumer Finance (2010), Pew Research Center

12

U.S. Census Bureau: Families and Living Arrangements, Table AD-1, Young Adults Living at Home: 1960 to

Present (2010).

13

National Association of Realtors: Profile of Homebuyers and Sellers (2011).

19

packaged into asset-backed securities, there may be additional complications stemming from

these changes in ownership.

Given the severe impacts that defaulting on student loans can have on young consumers,

policymakers might consider identifying potential opportunities for facilitating student loan

modifications and helping student borrowers emerge from financial distress.

Recommendations for the Secretary of the Treasury, the Director

of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and the Secretary of

Education

Assess whether efforts to correct problems in mortgage servicing could be

applied to improve the quality of student loan servicing

As seen in other product verticals, ordinary market forces may not apply in loan servicing. The

servicer’s customer is often a lender or group of investors— not the actual borrower. Since it is

inordinately difficult to refinance, borrowers cannot easily take their business elsewhere.

We have seen that inadequate investment in servicing processes can cause harm to consumers in

the mortgage market. For example, many families dealt with damaged credit and improper

foreclosures due to poor servicing practices. In the mortgage servicing market, policymakers and

regulators found it necessary to provide for more adequate oversight over servicers, as well as

more specific guidance to ensure reasonable levels of customer service.

Given the negative impact a servicing error can have on a consumer’s financial future, it would

be prudent to validate the existence of any systemic issues in the student loan servicing market,

14

correct and contain servicing errors, and further determine whether additional guidelines are

necessary.

Continue initiatives to increase adoption of the Income-Based Repayment

program for federal student loans

Many private student loan borrowers struggling to manage their debt have also borrowed federal

student loans. Since borrowers have generally been unable to obtain loan modifications of

private student loans, one way they might be able to better meet the obligations of their private

student loan debt is to reduce their payments on the federal student loans through Income-Based

Repayment (IBR).

The Department of Education’s collaboration with the Department of the Treasury and the

Internal Revenue Service to streamline the IBR application process is a helpful development.

15

Additional enrollment options and further simplification could drive further adoption, leading to

positive spillovers in the private student loan market.

Agencies might also consider working with non-profit organizations on distressed borrower

hotlines to increase awareness of IBR and other programs. Similar efforts in the mortgage

market have provided critical information to millions of distressed homeowners.

14

In some cases, the CFPB may be unable to supervise certain nonbank student loan servicers without first defining

“larger participants” in the market subject to Section 1024 of the Dodd-Frank Act.

15

Direct Loan borrowers will be able to electronically import their tax data into their IBR applications, reducing the

need for manual submissions and data entry.

20

APPENDIX

FIGURE 1: PRIVATE STUDENT LOAN COMPLAINTS BY AGE COHORT

MARCH 2012 – SEPTEMBER 2012

Note: Consumers filing a complaint may be co-signers.

FIGURE 2: PRIVATE STUDENT LOAN COMPLAINTS BY ISSUE TYPE AND AGE COHORT

MARCH 2012 – SEPTEMBER 2012

18-21

n=18

22-29

n=894

30-34

n=340

33-49

n=312

50-64

n=187

65+

n=45

52

319

881

20

115

177

10

75

147

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

900

1000

Getting a loan Problems when you are

unable to pay

Repaying your loan

18-34

35-49

50+

21

Contact Information

TO REACH THE CFPB’S OFFICE FOR STUDENTS

OR OFFICE OF INSTALLMENT & LIQUIDITY LENDING:

Mailing Address:

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau

1700 G Street NW

Washington, DC 20552

TO FILE A COMPLAINT:

Webpage: http://www.consumerfinance.gov/complaint

Toll-Free: (855) 411-CFPB (2372)

Español : (855) 411-CFPB (2372)

TTY/TDD: (855) 729-CFPB (2372)

Fax: (855) 237-2392

Mailing Address:

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau

PO Box 4503

Iowa City, Iowa 52244

PRESS & MEDIA REQUESTS

Email: press@consumerfinance.gov