Assessing

fitness to drive

for commercial and

private vehicle drivers

2022 EDITION

Medical standards for

licensing and clinical

management guidelines

A web version of the medical standards is available from the Austroads website: www.austroads.com.au

Help for professionals

For guidance in assessing a patient’s fitness to drive contact your State or Territory driver licensing authority

(seeAppendix 9 for details). Information is also available from the Austroads website: www.austroads.com.au

Assessing Fitness to Drive

First Published 1998

Second Edition 2001

Third Edition 2003

Reprinted 2006

Fourth Edition 2012

Reprinted 2013

Fifth Edition 2016

Reprinted 2017

Sixth Edition 2022

© Austroads Ltd 2022

This work is copyright. Apart from any use as

permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part

maybe reproduced by any process without the

priorwritten permission of Austroads.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-

Publication data

Assessing Fitness to Drive 2022

ISBN: Hardcopy 978-1-922700-17-9;

PDF 978-1-922700-21-6

Austroads Publication Number: AP-G56-22

Published by Austroads Ltd

Level 9, 570 George Street

Sydney NSW 2000 Australia

Phone: +61 2 8265 3300

Email: [email protected]

www.austroads.com.au

Austroads believes this publication to be correct at the

time of printing and does not accept responsibility for

any consequences arising from the use of information

herein. Readers should rely on their own skill and

judgement to apply information to particular issues.

Assessing

fitness to drive

for commercial and

private vehicle drivers

2022 EDITION

Medical standards for

licensing and clinical

management guidelines

About Austroads and the NTC

Austroads

Austroads is the collective of the Australian and

New Zealand transport agencies, representing

all levels of government. Austroads’ purpose

is to support its member organisations to

deliver an improved Australasian road transport

network. To succeed in this task, Austroads

undertakes leading-edge road and transport

research which underpins its input to policy

development and published guidance on the

design, construction and management of the

road network and its associated infrastructure.

Austroads also supports its members to achieve

consistency and improvements in the application

of registration and licensing practices, processes

and systems.

National Transport Commission

The NTC is a national land transport reform

agency that supports Australian governments to

improvesafety, productivity and environmental

outcomes, provide for future technologies and

improve regulatory eciency.

The NTC has a legislative requirement to

develop, monitor and maintain uniform or

nationally consistent regulatory and operational

arrangements for road, rail and intermodal

transport.

As a key contributor to the national

reform agenda, the NTC is accountable to

Commonwealth, state and territory ministers who

are responsible for transport and infrastructure

and make up membership of the Infrastructure

and Transport Ministers’ Meeting (ITMM). The

NTC works closely with ITMM’s advisory body,

the Infrastructure and Transport Senior Ocials’

Committee, which includes the headsof

Commonwealth, state and territory agencies.

ii

About Austroads and the NTC

Acknowledgements

Setting these standards involved extensive

consultation across a wide range of stakeholders

including regulators, employers and health

professionals. The NTC and Austroads gratefully

acknowledge all contributors including the

members of the Advisory Group, the Medicinal

Cannabis Working Group, the project team and

consultants. In particular, the contributions of

various health professional organisations and

individual health professionals are invaluable to

the review process.

Advisory Group

Derise Cubin Access Canberra

Rebecca Wilson Access Canberra

Bill McKinley Australian Trucking Association

Dr Ramu Nachiappan Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine

Adam Cameron Department for Infrastructure and Transport

Scott Swain Department for Infrastructure and Transport

Amie Buisman Department of Transport (WA)

Karen Webb Department of State Growth

A/Prof. Sjaan Koppel Monash University Accident Research Centre

Andreas Blahous National Heavy Vehicle Regulator

Emily Hicks Oce of Road Safety

Parik Lumb Road Safety Commission

Prof. Nigel Stocks Royal Australian College of General Practitioners

Lee Cheetham Transport for NSW

Irene Siu Transport for NSW

Yessenia Pineda-De Leon Transport and Main Roads

Fiona Morris Department of Transport (Vic)

Dr Marilyn DiStefano Department of Transport (Vic)

Dr Sanjeev Gaya Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine

iiiii

About Austroads and the NTC Acknowledgements

Medicinal Cannabis Working Group

Dr Shruti Navathe Access Canberra

David Sutton Department for Infrastructure and Transport

Scott Swain Department for Infrastructure and Transport

Sharon Wishart Department of Transport (Vic)

Tim Umbers Department of Transport (Vic)

Amie Buisman Department of Transport (WA)

Sussan Osmond Department of Transport and Main Roads

Prof. Iain McGregor Lambert Initiative for Cannabinoid Therapeutics, USYD

Dr Tamara Nation National Institute of Integrative Medicine

A/Prof. Vicki Kotsirilos NICM, University of Western Sydney

Adelaide Jones Oce of Road Safety

Prof. Edward Ogden St Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne

Prof. Yvonne Bonomo St Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne

Sally Millward Transport for NSW

Dr Sanjeev Gaya Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine

Contributing health professional

organisations

The following organisations contributed

substantially to the review process:

• Australian and New Zealand Association of

Neurologists

• Australian Diabetes Society

• Australasian Sleep Association

• Cardiac Society of Australia and New

Zealand

• Cognitive Dementia and Memory Service

• Epilepsy Society of Australia

• Occupational Therapy Australia

• Optometry Australia

• Orthoptics Australia

• Stroke Society of Australasia

• The Royal Australian and New Zealand

College of Ophthalmologists

• The Royal Australian and New Zealand

College of Psychiatrists.

iv

Acknowledgements

Endorsements

These standards are endorsed by:

• Australasian Faculty of Occupational and Environmental Medicine

• Australasian Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine

• Australasian Sleep Association

• Australian and New Zealand Association of Neurologists

• Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine

• Australian Diabetes Society

• Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand

• Occupational Therapy Australia

• Royal Australian College of Physicians

Accepted Clinical Resource

Royal Australian College of General Practitioners

Legal disclaimer

These licensing standards and management

guidelines have been compiled using all

reasonable care, based on expert medical

opinion and relevant literature, and Austroads

believes them to be correct at the time of

publishing. However, neither Austroads nor

the authors accept responsibility for any

consequences arising from their application.

Health professionals should maintain an

awareness of any changes in healthcare

and health technology that may aect their

assessment of drivers. Health professionals

should also maintain an awareness of

changes in the law that may aect their legal

responsibilities.

Where there are concerns about a particular

set of circumstances relating to ethical or legal

issues, advice may be sought from the health

professional’s medical defence organisation or

legal advisor.

Other queries about the standards should be

directed to the relevant driver licensing authority.

viv

EndorsementsAcknowledgements

Foreword

In 2020, 1,106 people were killed on Australian

roads, and many tens of thousands were

hospitalised with serious injuries. The annual

economic cost of road crashes in Australia

is estimated to be $30 billion, which is

accompanied by devastating social impacts.

While many factors contribute to safety on the

road, driver health and fitness to drive is an

important consideration. Drivers must meet

certain medical standards to ensure their health

status does not unduly increase their crash risk.

Assessing fitness to drive is a joint publication

of Austroads and the National Transport

Commission (NTC) and details medical standards

for driver licensing purposes for use by health

professionals and driver licensing authorities.

The standards are approved by Commonwealth,

state and territory transport ministers and were

first published in their current form in 2003. The

previous edition was published in 2016.

Since its last publication, medical, legal and

social developments have required that the

medical criteria within the guidelines are

updated to ensure they are accurate and

reflect current practices. To this end, the NTC

reviewed the guidelines, taking into account

feedback from stakeholders, including medical

professionals and expert consultants.

This review produced revised guidelines in

draft form, for public consultation in May 2021.

Doctors, other health professionals, members

of the public, consumer groups, commercial

operators and drivers, transport peak bodies

and governments submitted comments to the

draft guidelines.

Austroads and the NTC acknowledge the

significant contribution of health professionals to

road safety. Health professionals, in partnership

with drivers, the road transport industry and

governments, play an essential role in keeping

all road users safe. Together we are working

towards further reducing, and eventually

eliminating, deaths and injuries from vehicle

crashes on Australian roads.

Dr Geo Allan

Chief Executive

Austroads

Dr Gillian Miles

Chief Executive Ocer and Commissioner

National Transport Commission

vi

Foreword

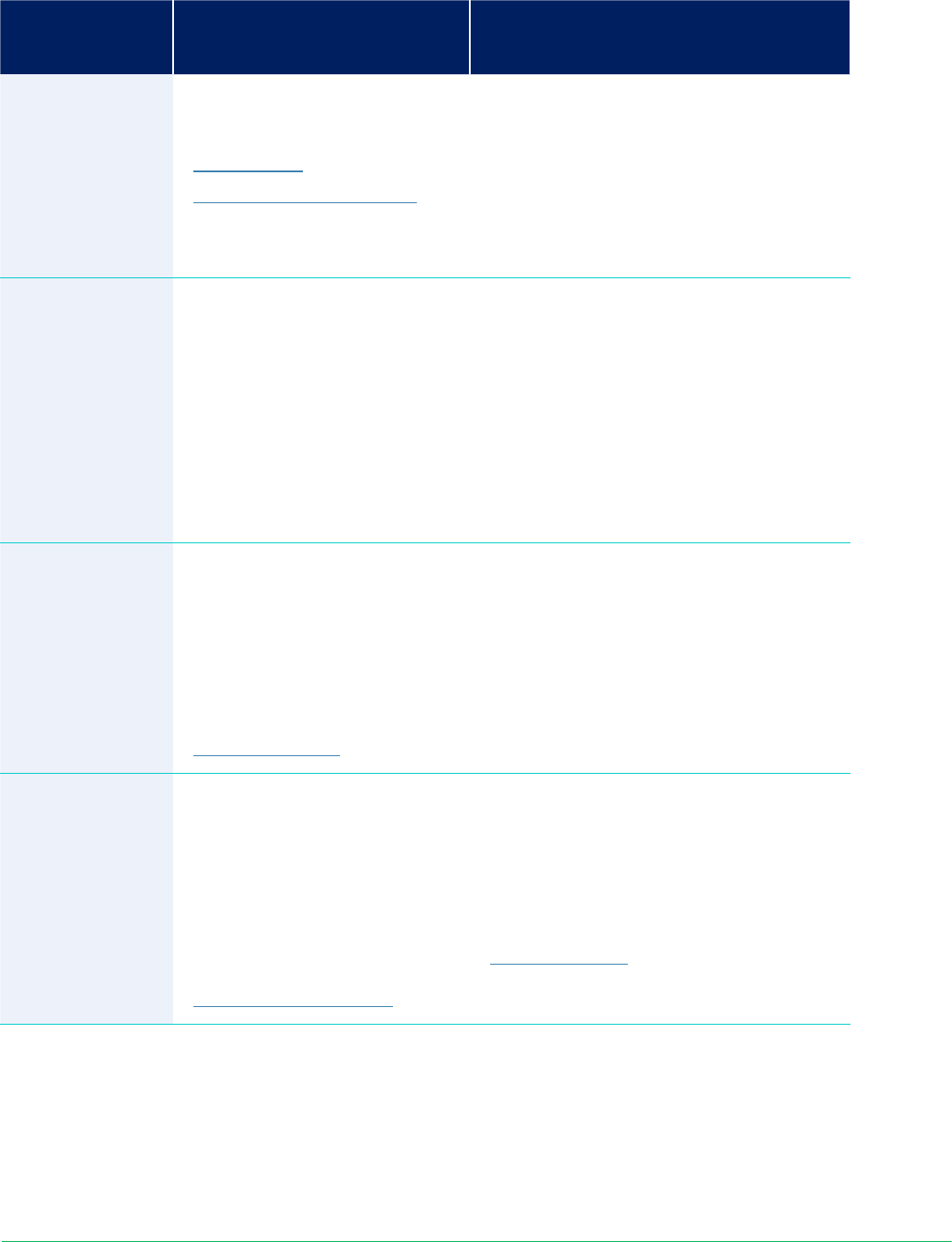

Contents

A web version of the medical standards is available from the Austroads website: www.austroads.com.au

Part A. Fitness to drive principles and practices 1

1. About this publication 2

1.1. Purpose 2

1.2. Target audience 3

1.3. Scope 3

1.4. Content 4

1.5. Development and evidence base 5

2. Assessing fitness to drive

–

generalguidance 7

2.1. The driving task 7

2.2. Impact of medical conditions on driving 10

2.3. Assessing and supporting functional driver capacity 21

3. Roles and responsibilities 25

3.1. Roles and responsibilities of driver licensing authorities 27

3.2. Roles and responsibilities of drivers 27

3.3. Roles and responsibilities of health professionals 28

4. Licensing and medical fitness to drive 34

4.1. Medical standards for private and commercial vehicle drivers 34

4.2. Considerations for commercial vehicle licensing 35

4.3. Prescribed periodic medical examinations for particular licensing/authorisation classes 37

4.4. Conditional licences 37

4.5. Reinstatement of licences or removal or variation of licence conditions 41

5. Assessment and reporting process

–

stepby step 42

5.1. Steps in the assessment and reporting process 43

5.2. Which forms to use 50

Part B. Medical standards 54

Fitness to drive assessment 55

1. Blackouts 57

1.1. Relevance to the driving task 57

1.2. General assessment and management guidelines 57

1.3. Medical standards for licensing 58

2. Cardiovascular conditions 63

2.1. Relevance to the driving task 63

2.2. General assessment and management guidelines 63

2.3. Medical standards for licensing 71

viivi

ContentsForeword

3. Diabetes mellitus 92

3.1. Relevance to the driving task 92

3.2. General assessment and management guidelines 92

3.3. Medical standards for licensing 99

4. Hearing loss and deafness 105

4.1. Relevance to the driving task 105

4.2. General assessment and management guidelines 106

4.3. Medical standards for licensing 109

5. Musculoskeletal conditions 112

5.1. Relevance to the driving task 112

5.2. General assessment and management guidelines

2

114

5.3. Medical standards for licensing 117

6. Neurological conditions 120

6.1. Dementia 121

6.2. Seizures and epilepsy 128

6.3. Other neurological and neurodevelopmental conditions 152

7. Psychiatric conditions 170

7.1. Relevance to the driving task 170

7.2. General assessment and management guidelines 171

7.3. Medical standards for licensing 175

8. Sleep disorders 179

8.1. Relevance to the driving task 179

8.2. General assessment and management guidelines 179

8.3. Medical standards for licensing 185

9. Substance misuse 190

9.1. Relevance to the driving task 190

9.2. General assessment and management guidelines 193

9.3. Medical standards for licensing 196

10. Vision and eye disorders 201

10.1. Relevance to the driving task 201

10.2. General assessment and management guidelines 202

10.3. Medical standards for licensing 209

viii

Contents

Part C. Appendices 214

Appendix 1. Regulatory requirements fordriver testing 215

Appendix 2. Forms 223

Appendix 3. Legislation relating to reporting 227

Appendix 4. Drivers’ legal BAC limits 235

Appendix 5. Alcohol interlock programs 237

Appendix 6. Disabled car parking and taxiservices 241

Appendix 7. Seatbelt use 243

Appendix 8. Helmet use 245

Appendix 9. Driver licensing authoritycontacts 247

Appendix 10. Specialist driver assessors 251

ixviii

ContentsContents

PART A.

Fitness to drive

principles and practices

1

PART A. Fitness to drive principles and practices

1

1. About this publication

1.1. Purpose

Driving a motor vehicle is a complex task

involving perception, appropriate judgement,

adequate response time and appropriate

physical capability. A range of medical

conditions, disabilities and treatments may

influence these driving prerequisites. Such

impairment may adversely aect driving ability,

possibly resulting in a crash causing death

orinjury.

The primary purpose of this publication is to

increase road safety in Australia by assisting

health professionals to:

• assess the fitness to drive of their patients in

a consistent and appropriate manner based

on current medical evidence

• promote the responsible behaviour of their

patients, having regard to their medical

fitness

• conduct medical examinations for the

licensing of drivers as required by state and

territory driver licensing authorities

• provide information to inform decisions on

conditional licences

• recognise the extent and limits of their

professional and legal obligations with

respect to reporting fitness to drive.

The publication also aims to provide guidance

to driver licensing authorities in making

licensing decisions. With these aims in mind the

publication:

• outlines clear medical requirements

for driver capability based on available

evidence and expert medical opinion

• clearly dierentiates between national

minimum standards (approved by the

Infrastructure and Transport Ministers’

Meeting) for drivers of commercial and

private vehicles

• provides general guidelines for managing

patients with respect to their fitness to drive

• outlines the legal obligations for health

professionals, driver licensing authorities

and drivers

• provides a reporting template to guide

reporting to the driver licensing authority

ifrequired

• provides links to supporting and

substantiating information.

Routine use of these standards will ensure the

fitness to drive of each patient is assessed in

a consistent manner. In doing so, the health

professional will not only be contributing to road

safety but may minimise medico-legal exposure

in the event that a patient is involved in a crash

or disputes a licensing decision.

This publication replaces all previous

publications containing medical standards

for private and commercial vehicle drivers

including Assessing fitness to drive

2001, 2003, 2012, 2016 (and its 2017

amendment) and Medical Examinations

for Commercial Vehicle Drivers 1997.

2

About this publication

1

PART A. Fitness to drive principles and practices

1

1.2. Target audience

This publication is intended for use by

any health professional who is involved

in assessing a person’s fitness to drive or

providing information to support fitness-to-

drivedecisionsincluding:

• medical practitioners (general practitioners

and specialists)

• optometrists

• orthoptists

• occupational therapists

• psychologists

• physiotherapists

• diabetes educators

• nurse practitioners and primary health care

nurses

• case workers.

The publication is also a primary source of

requirements for driver licensing authorities in

making determinations about medical fitness to

hold a driver licence.

1.3. Scope

1.3.1. Medical fitness for driver

licensing

This publication is designed principally to guide

and support assessments made by health

professionals regarding fitness to drive for

licensing purposes. It should be used by health

professionals when:

1. Treating any patient who holds a

driver licence whose condition may

aect their ability to drive safely.

Most adults drive, therefore a health professional

should routinely consider the impact of a

patient’s condition on their ability to drive safely.

Awareness of a patient’s occupation, licence

category (e.g. commercial, passenger vehicle)

or other driving requirements (e.g. shift work) is

also helpful.

2. Undertaking an examination at the

request of a driver licensing authority

or industry accreditation body.

Health professionals may be requested to

undertake a medical examination of a driver for

a number of reasons. This may be:

• for initial licensing of some vehicle classes

(e.g. multiple combination heavy vehicles)

• as a requirement for a conditional licence

• for assessing a person whose driving the

driver licensing authority believes may be

unsafe (i.e. ‘for cause’ examinations)

• for licence renewal of an older driver (in

certain states and territories)

• for licensing or accreditation of certain

commercial vehicle drivers (e.g. public

passenger vehicle drivers)

• as a requirement for Basic or Advanced

Fatigue Management under the National

Heavy Vehicle Accreditation Scheme (refer

to www.nhvr.gov.au).

This publication focuses on long-term health-

and disability-related conditions and their

associated functional eects that may impact

on driving. It sets out clear minimum medical

requirements for unconditional and conditional

licences that form the medical basis of decisions

made by the driver licensing authority. This

publication also provides general guidance with

respect to patient management for fitness to

drive. It does not address general management

of clinical conditions unless it relates to driving.

This publication outlines two sets of medical

standards for driver licensing or authorisation:

private vehicle driver standards and commercial

vehicle driver standards.

3

PART A. Fitness to drive principles and practices

The standards are intended for

application to drivers who drive within the

ambit of ordinary road laws. Drivers who

are given special exemptions from these

laws, such as emergency service vehicle

drivers, should have a risk assessment

and an appropriate level of medical

standard applied by their employer. At

a minimum, they should be assessed to

thecommercial vehicle standard.

1.3.2. Short-term fitness to drive

This publication does not attempt to address

the full range of health conditions that might

impact on a person’s fitness to drive in the

short term. Some guidance in this regard

is included in section 2.2.3. Temporary

conditions. In most instances, the non-driving

period for short-term conditions will depend

on individualcircumstances and should be

determined by the treating health professional

based on an assessment of the condition and

the potential risks.

1.3.3. Fitness for duty

The medical standards contained in this

publication relate only to driving. They cannot

be assumed to apply to fitness-for-duty

assessments (including fitness for tasks such

as checking loads, conversing with passengers

andundertaking emergency procedures)

without first undertaking a task risk assessment

that identifies the range of other requirements

for aparticular job.

1.4. Content

This publication is presented in three parts.

Part A comprises general information including:

• the principles of assessing fitness to drive

• specific considerations including:

− the assessment of people with multiple

medical conditions or age-related

change

− the management of temporary

conditions, progressive disorders and

undierentiated illness

− the eects of prescription and over-the-

counter drugs

− the role of practical driver assessments

and driver rehabilitation

• the roles and responsibilities of drivers,

licensing authorities and health professionals

• what standards to apply (private or

commercial) for particular driver classes

• the application of conditional licences

• the steps involved in assessing fitness

todrive.

Part B comprises a series of chapters relating to

relevant medical systems/diseases. The medical

requirements for unconditional and conditional

licences are summarised in a tabulated format

to dierentiate between the requirements

for private and commercial vehicle drivers.

Additional information, including the rationale for

the standards, as well as a general assessment

and management considerations, is provided in

the supporting text of each chapter.

Part C, the appendices, comprises further

supporting information including:

• regulatory requirements for driver

assessment in each jurisdiction

• guidance on forms for the examination

process and reporting to the driver

licensingauthority

• legislation relating to driver and health

professional reporting of medical conditions

4

About this publication

3

PART A. Fitness to drive principles and practices

• legislation relating to blood alcohol, seatbelt

use, helmet use and alcohol interlocks

• contacts for services relating to disabled

parking and transport, occupational therapist

assessments and driver licensing authorities.

1.5. Development and

evidence base

The evidence that underpin the licensing criteria

and guidance are sourced from medical and

fitness-to-drive studies, medical guidelines and

expert opinion. A reference list of important

studies is provided at the end of each chapter.

In addition to evidence regarding crash risk and

the eects of medical conditions on driving,

evidence has also been sought regarding best

practice approaches to driver assessment and

rehabilitation.

A key input in terms of evidence for the licensing

criteria remains the Monash University Accident

Research Centre report Influence of chronic

illness on crash involvement of motor vehicle

drivers: 3rd edition. This is an update of the

second (2010) edition of the report and provides

a comprehensive review of published studies

involving drivers of private and commercial

motor vehicles. The report investigates the

influence of selected medical conditions and

impairments on crash involvement, in the context

of condition prevalence and quality of evidence

of crash involvement.

1,2

In compiling this report, the Monash University

Accident Research Centre led an international

research consortium to compile, review and

interpret the best available evidence on each

topic. Nevertheless, for most conditions, the

report acknowledges the limited evidence

available and that the quality of evidence is

variable. In interpreting the research, there is

therefore a need to consider several sources of

potential bias including the following:

• There is a ‘healthy driver’ eect whereby

drivers with a medical condition may

recognise that they are not able to fully

control a car and may either cease driving

or restrict their driving. Their opportunity to

be in a crash is therefore reduced, and this

contributes to a lower crash risk than may

otherwise be expected.

• The definition and incidence of crashes

when driving often depends on self-

reporting, which may lead to over- or under-

reporting in some studies.

• The definition of a ‘medical condition’ is

by self-report in some studies and may not

beaccurate.

• The ‘exposure metric’ (i.e. kilometres

travelled) is often not controlled for, yet is

crucial for determining the risk of a crash.

• Sample sizes may be small and not

represent the general population of drivers.

• The control group may not be properly

matched by age and sex.

• Commercial drivers are rarely considered

as a separate cohort, and generalisations

based on evidence from private motor

vehicle drivers may not be appropriate.

• Studies rarely identify whether and how

drivers are treated/untreated – for example,

corrected vision for those with vision

impairments and hearing aids for those with

hearing impairments.

• Comorbidities may not be adjusted for

(e.g.alcohol dependence).

5

PART A. Fitness to drive principles and practices

The implications are that false-negative results

may occur whereby the condition appears

to have no eect or minimal eect on driving

safety. The authors acknowledge that care

should be taken in interpreting the literature

and that professional opinion plus other

relevant data should be taken into account

in determining the risks posed by medical

conditions. The authors also note that the

review focused on published peer-reviewed

literature. There was no inclusion of technical

reports, conference presentations or abstracts,

case studies, coroner reports or studies, cohort

studies (without a control group) or reviews of

consensus-based medical standards for any of

the medical conditions reviewed.

For the purposes of this publication the term

‘crash’ refers to a collision between two or

more vehicles, or any other accident or incident

involving a vehicle in which a person or animal is

killed or injured, or property is damaged.

Health professionals should also keep

themselves up to date with changes in medical

knowledge and technology that may influence

their assessment of drivers, and with legislation

that may aect the duties of the health

professional or the patient.

6

About this publication

5

PART A. Fitness to drive principles and practices

2. Assessing fitness to drive

–

generalguidance

The aim of determining fitness to drive is to

achieve a balance between:

• minimising any driving-related road safety

risks for the individual and the community

posed by the driver’s permanent or long-

term injury or illness,

• maintaining the driver’s lifestyle and

employment-related mobility independence.

The key question is: Is there a likelihood

the person will be unable to control the

vehicle and/or unable to act or react

to the driving environment in a safe,

consistent and timely manner?

The main considerations in making this

assessment are:

• the driving task, including the person’s

individual driving requirements and mobility

needs (refer to section 2.1. The driving task)

• the potential impacts of medical conditions,

disabilities and treatments (refer to section

2.2. Impact of medical conditions on

driving)

• the driver’s functional abilities including their

capacity to compensate and the need for

rehabilitation (refer to section 2.3. Assessing

and supporting functional driver capacity).

The general guidance provided in this section

should be considered in conjunction with the

specific criteria and management guidelines for

individual conditions outlined in Part B of this

publication.

In light of the information gathered across these

areas, the health professional may advise the

patient regarding their fitness to drive and

provide advice to the driver licensing authority

(refer to section 3. Roles and responsibilities).

The threshold tolerance is much less for

commercial vehicle drivers where there is the

potential for more time on the road and more

severe consequences in the event of a crash

(refer to section 4.1. Medical standards for

private and commercial vehicle drivers). In

cases where a person may only be fit to drive in

some circumstances or requires periodic review

to monitor the progression of their condition, the

health professional may advise conditions under

which driving could be performed safely (refer to

section 4.4. Conditional licences).

Detailed steps for performing the assessment

and managing the outcome are found in section

5. Assessment and reporting process – stepby

step.

2.1. The driving task

An understanding of the driving task, both

generally and for the specific driver, underpins

the assessment of fitness to drive and guides

the determination of risk associated with

impairment due to ill health.

Driving is a complex instrumental activity of daily

living, characterised by a rapidly repeating cycle

in which:

• Information about the vehicle and road

environment is obtained via the visual and

auditory senses.

• The information is operated on by several

cognitive processes, which leads to

decisions about driving.

• Decisions are put into eect via the

musculoskeletal system, which acts on

the various controls to alter the vehicle in

relation to the road (refer to Figure 1).

7

PART A. Fitness to drive principles and practices

This repeating sequence depends on:

Sensory input

• vision

• visuospatial perception

• hearing

• proprioception

• kinesthesia

Motor function

• muscle power

• coordination

Cognitive function

• attention and concentration

• comprehension

• memory

• insight

• judgement

• decision making

• reaction time

• sensation.

Given these requirements, it follows that many

body systems need to be functional to ensure

safe and timely execution of the skills required

for driving.

Furthermore, the demands of the specific driving

task can vary considerably depending on a

range of factors including those relating to the

driver, the vehicle, the purpose of the driving

task and the road environment (Box 1). For

commercial drivers in particular these demands

can be significant, as can be the consequences

for public safety.

Assessing health professionals should

document the individual’s driving

requirements and driving history as part

ofthe assessment process.

8

Assessing fitness to drive – generalguidance

7

PART A. Fitness to drive principles and practices

Figure 1. The driving task

Box 1. Factors aecting driving

Driving tasks occur within a dynamic system influenced by complex driver, vehicle, task,

organisational and external road environment factors including:

• the driver’s experience, training and attitude

• the driver’s physical, mental and emotional health – for example, fatigue and the eect of

substance misuse including illicit, prescription and non-prescription drugs

• the road system – for example, signs, other road users, trac characteristics and road layout

• legal requirements – for example, speed limits and blood alcohol concentration

• the natural environment – for example, night, extremes of weather and glare

• vehicle and equipment characteristics – for example, the type of vehicle, braking

performance and maintenance

• mental workload and distraction due to in-vehicle technologies (e.g. GPS, vehicle warning/

alert systems, driver assistance systems) and communication systems (hands-free phone/

email systems)

• personal requirements, trip purpose, destination, appointments, navigation tasks and time

pressures

• passengers, in-vehicle communication/entertainment devices and their potential to distract

the driver.

For commercial or heavy vehicle drivers there is a range of additional factors including:

• business requirements – for example, rosters (shifts), driver training and contractual demands

• work-related multitasking – for example, interacting with in-vehicle technologies such as a

GPS, job display screens or other communication systems

• legal requirements – for example, work diaries and licensing procedures

• vehicle issues including size, stability and load distribution

• passenger requirements/issues – for example, duty of care, communication requirements

and potential for occupational violence

• risks associated with carrying dangerous goods

• additional skills required to manage the vehicle – for example, turning and braking

• endurance/fatigue and vigilance demands associated with long periods spent on the road.

Sensory input

Musculoskeletal actions

Vehicle–road interaction

Cognitive input

9

PART A. Fitness to drive principles and practices

2.2. Impact of medical

conditions on driving

2.2.1. Assessing medical conditions

Reflecting the requirements of the driving

task (section 2.1. The driving task), the key

domains to consider when assessing the

impact of medical conditions and disabilities

ondrivingare:

• impairment of:

− sensory function (in particular, visual

acuity and visual fields but also

cutaneous, muscle and joint sensation)

− motor function (e.g. joint movements,

strength, endurance and coordination)

− cognition (e.g. attention, concentration,

memory, problem-solving skills, thought

processing, visuospatial skills, insight and

judgement)

• the risk of sudden incapacity (leading to

sudden loss of control of the vehicle).

Such impacts may be associated with a range of

medical conditions. Conditions with the potential

to cause significant impairment and/or sudden

incapacity are the focus of this publication and

include:

• blackouts

• cardiovascular conditions

• diabetes

• hearing loss and deafness

• musculoskeletal conditions

• neurological conditions

• psychiatric conditions

• substance misuse/dependency

• sleep disorders

• vision problems.

The impairments/impacts associated with

medical conditions may be framed in a number

of ways. For example, impairments may:

• Be persistent (e.g. visual impairment) or

episodic (e.g. seizure, severe hypoglycaemic

event). Drivers with persistent impairments

can be assessed based on observations and

measures of their functional capacity. Those

with episodic impairment must be assessed

based on a risk analysis that considers the

probability and consequence of the episode,

as well as any triggering factors and whether

they can be avoided.

• Fluctuate, for example, the capacity of

people living with dementia can fluctuate

both day to day and within a 24-hour period.

It is important that the assessor considers

the potential of fluctuating capacity and

theimpact these factors may have on

drivingability.

• Be progressive (e.g. dementia, progressive

neurological conditions, end-organ

aects associated with diabetes) or

static (permanent disabilities), which has

implications for ongoing monitoring (refer

to section 2.2.5. Progressive conditions).

Many people with a long-term condition

or disability may have developed coping

strategies to enable safe driving (refer

to section 2.2.6. Congenital conditions,

disability and driving).

• Become introduced through use of

medications that eect cognition and

reaction time (refer to section 2.2.9. Drugs

and driving).

• Resolve with treatment (e.g. following

rehabilitation for stroke), which has

implications for reinstating of unconditional

licences (refer to section 4.5. Reinstatement

of licences or removal or variation of

licence conditions).

10

Assessing fitness to drive – generalguidance

9

PART A. Fitness to drive principles and practices

2.2.2. Conditions not covered

explicitly in this publication

This publication does not attempt to define

all clinical situations that may influence safe

driving ability.

It is accepted that other medical conditions or

combinations of conditions may also be relevant

and that it is not possible to define all clinical

situations where an individual’s overall function

would compromise public safety. A degree of

professional judgement is therefore required in

assessing fitness to drive.

The examining health professional should

follow general principles when assessing

these patients including consideration of the

driving task and the potential impact of the

condition on requirements such as sensory,

motor and cognitive skills. Episodic conditions

need consideration regarding the likelihood of

recurrence. A more stringent threshold should

be applied to drivers of commercial vehicles

than to private vehicle drivers. An appropriate

period should be advised for review, depending

on the natural history of the condition.

2.2.3. Temporary conditions

This publication does not attempt to address

every condition or situation that might

temporarily aect safe driving ability.

There are a wide range of conditions that

temporarily aect the ability to drive safely.

These include conditions such as post-surgery

recovery, severe migraine or injuries to limbs.

These conditions are self-limiting and hence do

not aect licence status; therefore, the licensing

authority does not need to be informed.

The treating health professional should

provide suitable advice to such patients

about driving safely including recommended

periods of abstinence from driving, particularly

for commercial vehicle drivers. Such advice

shouldconsider the likely impact of the patient’s

condition and their specific circumstances on

the driving task as well as their specific driving

requirements. Table 1 provides guidance on

some common conditions that may temporarily

aect driving ability.

2.2.4. Undierentiated conditions

A patient may present with symptoms that could

have implications for their licence status but

where the diagnosis is not clear. Investigating

the symptoms will mean there is a period of

uncertainty before a definitive diagnosis is made

and before the licensing requirements can be

confidently applied.

Each situation will need to be assessed

individually, with due consideration given to the

probability of a serious disease or long-term

injury or illness that may aect driving, and to

the circumstances in which driving is required.

However, patients presenting with symptoms

of a serious nature – for example, chest pains,

dizzy spells, blackouts or delusional states

– should be advised not to drive until their

condition can be adequately assessed. During

this interim period, in the case of private vehicle

drivers, no formal communication with the driver

licensing authority is required unless there is

significant risk to public health (refer to section

3.3.1. Confidentiality, privacy and reporting to

the driver licensing authority). After a diagnosis

is firmly established and the standards applied,

normal notification procedures apply.

In the case of a commercial vehicle driver

presenting with symptoms of a potentially

serious nature, the driver should be advised to

stop driving and to notify the driver licensing

authority. The health professional should

consider the impact on the driver’s livelihood and

investigate the condition as quickly as possible.

11

PART A. Fitness to drive principles and practices

Table 1. Examples of how to manage temporary conditions

Condition and impact on driving Management guidelines

Anaesthesia and sedation

3

Physical and mental capacity may be impaired for some

time post anaesthesia (including general anaesthesia,

local anaesthesia and sedation). The eects of general

anaesthesia will depend on factors such as the duration

of anaesthesia, the drugs administered and the surgery

performed. The eect of local anaesthesia will depend

on dosage and the region of administration. Analgesic

and sedative use should also be considered.

In cases of recovery following surgery or procedures

under general anaesthesia, local anaesthesia or

sedation, it is the responsibility of the surgeon/dentist

and anaesthetist to advise patients not to drive until

physical and mental recovery is compatible with safe

driving.

• Following minor procedures under local anaesthesia

without sedation (e.g. dental block), driving may be

acceptable immediately after the procedure.

• Following brief surgery or procedures with short-

acting anaesthetic drugs or sedation, the patient may

be fit to drive after a normal night’s sleep.

• After longer surgery or procedures requiring general

anaesthesia or sedation, it may not be safe to drive

for 24 hours or more.

Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

While deep vein thrombosis may lead to an acute

pulmonary embolus, there is little evidence that

such an event causes crashes. Therefore there is no

licensing standard applied to either condition. Non-

driving periods are advised. If long-term anticoagulation

treatment is prescribed, the standard for anticoagulant

therapy should be applied (refer to Part B section 2.2.8.

Long-term anticoagulant therapy).

Private and commercial vehicle drivers should be

advised not to drive for at least 2 weeks following a

deep vein thrombosis and for 6 weeks following a

pulmonary embolism.

Medications or other treatments

Adaptation to new drug/medication regimens or

undergoing some treatments (e.g. radiation therapy or

haemodialysis) may require a non-driving period.

The non-driving period should be determined by the

treating health professionals based on a consideration

of the requirements of the driving task and the impact of

medications or treatments on the capacity to undertake

these tasks, including responding to emergency

situations. A practical driver assessment may be helpful

in determining fitness to drive (refer to section 2.3.1.

Practical driver assessments).

Post-surgery

Surgery will aect driving ability to varying degrees

depending on the location, nature and extent of

theprocedure.

The non-driving period post-surgery should be

determined by the treating health professionals based

on a consideration of the requirements of the driving

task and the impact of the surgery on the capacity

to undertake these tasks, including responding to

emergency situations. A practical driver assessment

may be helpful in determining fitness to drive (refer to

section 2.3.1. Practical driver assessments).

12

Assessing fitness to drive – generalguidance

11

PART A. Fitness to drive principles and practices

Condition and impact on driving Management guidelines

Pregnancy

Under normal circumstances pregnancy should not be

considered a barrier to driving. However, conditions that

may be associated with some pregnancies should be

considered when advising patients. These include:

• fainting or light-headedness

• hyperemesis gravidarum

• hypertension of pregnancy

• post caesarean section.

A caution regarding driving may be required depending

on the severity of symptoms and the expected eects of

medication.

Seatbelts must be worn (refer to Appendix 7. Seatbelt

use).

Temporary or short-term vision impairments

A number of conditions and treatments may impair

vision in the short term – for example, temporary

patching of an eye, use of mydriatics or other drugs

known to impair vision, or eye surgery. For long-term

vision problems, refer to Part B section 10. Vision and

eye disorders.

People whose vision is temporarily impaired by a

short-term eye condition or an eye treatment should be

advised not to drive for an appropriate period.

2.2.5. Progressive conditions

Often diagnoses of progressive conditions

are made well before there is a need to

question whether the patient remains safe to

drive (e.g. multiple sclerosis, early dementia).

However, it is important to raise issues relating

to the likely eects of these disorders on

personal independent mobility early in the

managementprocess.

The patient should be advised appropriately

where a progressive condition is diagnosed that

may result in future restrictions on driving. It is

important to give the patient as much lead time

as possible to make the lifestyle changes that

may later be required (e.g. adaptation to using

public transport and/or a motorised mobility

device). Assistance from an occupational

therapist may be valuable in such instances

(refer to Part B section 6.1. Dementia).

2.2.6. Congenital conditions,

disability and driving

Congenital conditions and long-term or

permanent disabilities may have an impact on a

person’s ability to drive safely. The physical and

cognitive implications of such conditions may

include (but are not limited to):

• diculty sustaining concentration or

switching attention between multiple

drivingtasks

• reduced cognitive and perceptual

processing speeds, including reaction times

• reduced performance in complex situations

(e.g. when there are multiple distractions)

• reduced information processing and

judgement

• diculty anticipating and responding to

other road users

• diculty controlling movement

• reduced joint range of motion and

musclestrength.

These impacts vary and many people develop

coping strategies to enable safe driving.

13

PART A. Fitness to drive principles and practices

Individual assessment is therefore required

based the general principles, the stability of the

disability and bodily systems that underpin any

adaptive behaviours for driving.

Legal obligations for reporting to the driver

licensing authority apply (refer to section 3.2.

Roles and responsibilities of drivers). This

may trigger the need to provide a medical

report and/or an occupational therapy driving

assessment. An occupational therapist driver

assessor can provide information about how

a condition or disability may aect driving or

learning to drive. They can also oer advice

about potential aids, vehicle modifications or

training strategies that may assist the individual.

The outcomes of the assessment may result in

the requirement of a conditional licence relating

to the driver (e.g. prosthesis must be worn) or

the vehicle (e.g. can only drive a vehicle with

certain modifications); refer to section 4.4.

Conditional licences. If the condition or disability

is assessed as static, then it is unlikely to require

periodic review.

Learning to drive

People with a disability that may impact their

ability to drive can seek the opportunity to gain

a driver licence. This opportunity is increasingly

available through the National Disability

Insurance Scheme. To ensure they receive

informed advice and reasonable opportunities

for training, it is helpful if they are trained by a

driving instructor with experience in teaching

drivers with disabilities. An initial assessment

with an occupational therapist specialised in

driver evaluation may help to identify the pre-

requisite functional capacity requirements to

realistically aspire to driving independence,

need for adaptive devices, vehicle modifications

or special driving techniques.

National Disability Insurance Scheme

There are support options to help drivers with

a disability through the National Disability

Insurance Scheme (NDIS). The NDIS provides

all Australians under the age of 65 who have

a permanent and significant disability with

reasonable and necessary supports.

The NDIS may provide assistance with the

medical review process including obtaining a

driver licence, medical reports, occupational

therapist driving assessments, driver training and

vehicle modifications. Further information about

the support provided by the NDIS and how to

access the services can be found on the NDIS

website at www.ndis.gov.au.

2.2.7. Older drivers and age-related

changes

While advanced age in itself is not a barrier to

safe driving, age-related physical and mental

changes will eventually aect a person’s

ability to drive safely. Given the association

between health outcomes, mobility and social

connectedness, fitness to drive should be

proactively managed, with the goal of enabling

older people to continue to drive for as long as it

is safe to do so.

Crash data points to some of the vulnerabilities

of older drivers, showing that they are more

likely to crash at intersections and with other

vehicles (multi-vehicle crashes). Frailty of older

drivers is also associated with higher risk of

injury and death. At the same time, safety

risks for older drivers may be mitigated by

their extensive driving experience and their

tendency to modify their driving to suit their

capabilities, including avoiding peak-hour trac,

poor weather and night driving, and driving at

slowerspeeds.

14

Assessing fitness to drive – generalguidance

13

PART A. Fitness to drive principles and practices

Management approach

A proactive approach to management of older

drivers encompasses primary, secondary and

tertiary prevention.

Discussions about mobility and driving

Talking with an older person about their driving

can be dicult, particularly if it is delayed until

the conversation is about ceasing driving.

Early conversations focused on maintenance

of driving ability in the context of their general

health, mobility needs and other activities of daily

living can help build self-awareness, enable self-

monitoring and normalise the eventual transition

to non-driving. Driver licensing authorities

provide resources to support conversations with

older drivers and their carers/families.

Active observation and screening

Routine care of the older person should

include monitoring for decline in the functions

necessary for driving, including vision, cognition

and motor/sensory functions (see below). This

is also an opportunity to pick up on ‘red flags’

such as falls, memory problems, confusion,

caregiver concerns or a sudden change in social

circumstances. Annual checks, such as through

the Medicare 75 Plus health check, provide an

opportunity for screening and for considering

the overall impacts of ageing and multiple

medical conditions on driving.

Early intervention

Early identification of functional decline can

provide opportunities to address driving

skills and capabilities in at-risk drivers. This

may involve referral for relevant assessment

and management (e.g. allied health, driver

assessment), including treatments, driving

rehabilitation, vehicle modifications and driving

restrictions (refer to section 2.3. Assessing and

supporting functional driver capacity). In cases

where an older person is not fully fit to drive

in all circumstances, the health professional

may advise conditions under which driving

could be performed safely (refer to section 4.4.

Conditional licences). Referral to a geriatrician

may also assist if there is doubt about a patient’s

fitness to drive or about remedial strategies.

Considering the impact of medical conditions

on driving

Most older adults have at least one chronic

medical condition. The most common conditions

include cardiovascular disease, stroke,

Parkinson’s disease, sleep disorders, cataracts,

glaucoma, musculoskeletal impairments

including arthritis, depression, dementia

and diabetes. The overall impact of multiple

conditions on driving will need to be considered

(refer to section 2.2.8. Multiple medical

conditions). A new diagnosis or change in any

condition, or an acute medical event, is a trigger

to revisit driving, so too is the addition of a new

medication or treatment. Older adults often take

multiple medications, and this is associated with

increased crash risk. Counselling regarding

medications should specifically address

potential safety concerns for driving, including

any age-associated eects such as changed

drug metabolism (refer to section 2.2.9. Drugs

and driving).

Transition to alternative means of transport

Ultimately, when a person’s functioning is no

longer compatible with safe driving, they will

need to be supported in relinquishing their

licence and seeking alternative modes of

transport. There is a role for ongoing monitoring

of health and social consequences and

compliance with advice not to drive. Caregivers

play an important role in encouraging the

older person to cease driving and to help the

individual find alternatives.

15

PART A. Fitness to drive principles and practices

Assessing older drivers

Age-related physical and mental changes

vary greatly between individuals. The three

main functional areas to consider for the

assessment and routine care of older drivers are

described below. Health professionals should

be mindful that a driver may have several minor

impairments that alone may not aect driving but

when taken together may make risks associated

with driving unacceptable (refer to section 2.2.8.

Multiple medical conditions).

Some driver licensing authorities require regular

medical examination or assessment of drivers

beyond a specified age. These requirements

vary between jurisdictions and may be viewed

inAppendix 1. Regulatory requirements

fordriver testing.

Vision

Various aspects of vision may decline with

age, including acuity, visual fields and contrast

sensitivity. Eye conditions such as cataracts,

glaucoma and macular degeneration are also

more common in older people. The gradual

changes associated with ageing and the gradual

onset of eye conditions may not be noticed

by the driver. Regular eye health checks may

facilitate early detection and management for

changes in vision. Diculty driving at night and

problems with glare may be early signs of age-

related visual decline and may be investigated

in routine conversations. Driving restrictions/

conditions such as no-night driving can help

maintain safe driving, while removal of cataracts

can eectively restore vision for driving. (Refer

also to section 4.4. Conditional licences and

Part B section 10. Vision and eye disorders).

Cognition

Various aspects of cognitive processing

required for safe driving can decline with

age, including memory, working memory,

visual processing, visuospatial skills, attention

functioning, executive functioning and insight.

These impairments can aect a person’s ability

to process and respond to the complex road

environment. The impairments can vary from

day to day, which can present a challenge for

definitive assessment in relation to driving.

Dementia is a particular concern as older adults

with dementia often lack insight into theirdeficits

and may be more likely to drive when it is unsafe

(refer also to Part B section 6.1. Dementia).

Motor and somatosensory function

Ageing generally results in a decline in muscle

strength and endurance, as well as reduced

flexibility, range of movement and joint stability.

Musculoskeletal conditions such as arthritis

are also more prevalent in older adults. These

and other general health conditions may be

associated with chronic pain and fatigue.

Proprioception may also be an issue.

Older adults with these impairments may have

diculties getting in and out of the car, using the

seatbelt and ignition key, adjusting mirrors and

seats, steering, turning to reverse, and using foot

pedals. Adaptative equipment, some requiring

professional recommendation, is available to

support drivers experiencing pain, reduced

reach or reduced strength. Rehabilitative

therapies may improve the older driver’s

functioning and endurance (refer to section

2.3.2 Driver rehabilitation, Part B section

5. Musculoskeletal conditions).

16

Assessing fitness to drive – generalguidance

15

PART A. Fitness to drive principles and practices

More information

Reference to the Royal Australian College

of General Practitioners’ Guidelines for

preventative activities in general practice (the

‘Red Book’) and the Aged care clinical guide

(the ‘Silver Book’) may assist in assessing older

drivers.

3,4

Additional resources and references

that may support assessment are provided in

Part A, References and further reading.

5–11

2.2.8. Multiple medical conditions

Where a vehicle driver has multiple conditions

or a condition that aects multiple body systems,

there may be an additive or a compounding

detrimental eect on driving abilities – for

example in:

• congenital disabilities such as cerebral palsy,

spina bifida and various syndromes

• multiple trauma causing orthopaedic and

neurological injuries as well as psychiatric

sequelae

• multi-system diseases such as diabetes,

connective tissue disease, multiple sclerosis

and systemic lupus erythematosus

• dual diagnoses involving psychiatric illness

and drug or alcohol addiction

• ageing-related changes in motor, cognitive

and sensory abilities together with

degenerative disease

• chronic pain.

Although these medical standards are designed

principally around individual conditions, clinical

judgement is needed to integrate and consider

the eects on safe driving of any medical

conditions and disabilities that a patient may

present with. However, it is insucient simply

to apply the medical standards contained in

this publication for each condition separately

because a driver may have several minor

impairments that alone may not aect driving but

when taken together may make risks associated

with driving unacceptable. Therefore, it is

necessary to integrate all clinical information,

bearing in mind the additive or compounding

eect of each condition on the overall capacity

of the patient to drive safely.

Where one or more conditions are progressive,

it may be important to reduce driving exposure

and ensure ongoing monitoring of the patient

(refer to section 2.2.5. Progressive conditions).

Conditional licences that may limit the driver (e.g.

no night driving) or place requirements on the

vehicle (e.g. automatic transmission only) are an

option in these circumstances (refer to section

4.4. Conditional licences). The requirement

for periodic reviews can be included as

recommendations on driver licences.

Periodic reviews are also important for drivers

with conditions likely to be associated with

future reductions in insight and self-regulation.

If lack of insight may become an issue in the

future, it is important to advise the patient to

report the condition(s) to the driver licensing

authority. Where lack of insight already appears

to impair self-assessment and judgement,

public safety interests should prevail, and the

health professional should report the matter

directly to the driver licensing authority and, if

appropriate, seek the support of the patient’s

family members.

2.2.9. Drugs and driving

Any drug that acts on the central nervous system

has the potential to adversely aect driving

skills. Central nervous system depressants,

for example, may reduce vigilance, increase

reaction times and impair decision making

in a very similar way to alcohol. In addition,

drugs that aect behaviour may exaggerate

adverse behavioural traits and introduce risk-

takingbehaviours.

Where medication is relevant to the overall

assessment of fitness to drive in managing

specific conditions such as diabetes, epilepsy

and psychiatric conditions, this is covered in

17

PART A. Fitness to drive principles and practices

the respective chapters. Prescribing doctors

and dispensing pharmacists do, however, need

to be mindful of the potential eects of all

prescribed and over-the-counter medicines and

to advise patients accordingly. Patients receiving

continuing long-term drug treatment should be

evaluated for their reliability in taking the drug

according to directions. They should also be

assessed for their understanding that medicines

can have undesired consequences that may

impair their ability to drive safely and this may be

unexpectedly aected by other factors such as

drug interactions.

General guidance for prescription drugs

and driving

While many drugs have eects on the central

nervous system, most, with the exception of

benzodiazepines, tend not to pose a significantly

increased crash risk when the drugs are used

as prescribed and once the patient is stabilised

on the treatment. This may also relate to drivers

self-regulating their driving behaviour. When

advising patients and considering their general

fitness to drive, whether in the short or longer

term, health professionals should consider:

• the balance between potential impairment

due to the drug and the patient’s

improvement in health on safe driving ability

• the individual response of the patient –

some people are more aected than others

• the type of licence held and the nature of

the driving task (i.e. commercial vehicle

driver assessments should be more

stringent)

• the added risks of combining two or more

drugs capable of causing impairment,

including alcohol

• the added risks of sleep deprivation on

fatigue while driving, which is particularly

relevant to commercial vehicle drivers

• the potential impact of changing medications

or changing dosage

• the cumulative eects of medications

• the presence of other medical conditions

that may combine to adversely aect

drivingability

• other factors that may exacerbate risks such

as known history of alcohol or drug misuse.

Acute alcohol and drug intoxication

Acute impairment due to alcohol or drugs

(including illicit, prescription and over-the-

counter drugs) is managed through specific

road safety legislation that prohibits driving

over a certain blood alcohol concentration

(BAC), with the presence of certain drugs in

bodily fluids, or when driving is impaired by

drugs (refer to Appendix 4. Drivers’ legal

BAC limits). This may include requirements

for using alcohol interlocks, the application

of which varies between jurisdictions (refer

to Appendix 5. Alcohol interlock programs).

This is a separate consideration to long-term

medical fitness to drive and licensing, therefore

specific medical requirements are not provided

in this publication. Dependency and substance

misuse, including chronic misuse of illicit,

non-prescription and prescription drugs, is a

licensing issue and standards are outlined in

Part B section 9. Substance misuse.

Further guidance for prescribing drugs of

dependence can be found in the Royal

Australian College of General Practitioners’

guide Prescribing drugs of dependence in

general practice (visit www.racgp.org.au).

18

Assessing fitness to drive – generalguidance

17

PART A. Fitness to drive principles and practices

The eects of specific drug classes

13,14

Medicinal cannabis (cannabinoids)

15–25,36,37

Medicinal cannabis refers to medically

prescribed cannabis preparations intended

for therapeutic use, including pharmaceutical

cannabis preparations with set amounts of

cannabinoids such as oils, tinctures, sprays and

other extracts. The main active components of

cannabis (medicinal or recreational) are delta-

9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol

(CBD). THC, the psychoactive ingredient in

cannabis (including medicinal), can cause

cognitive and psychomotor impairments that

degrade the ability to drive safely including

attention and concentration deficits, mild

cognitive impairment, dizziness and anxiety.

These deficits can begin at low doses and are

highly individualised.

The pharmacokinetics of cannabinoids are

complex, making it dicult to predict the severity

of impairment. Other influencing factors include

the history of use, frequency of dose, ratio

of cannabinoids and route of administration

(vaporised, oral, oral-mucosal, transdermal). The

onset and duration of impairing eects can vary

significantly between individuals. The eects can

typically last for three to six hours after inhalation

or five to eight hours after oral administration,

but may be significantly longer for either route

of administration and should be determined

individually. Further information on the route

of administration and THC pharmacokinetic/

pharmacodynamics can be found in the TGA’s

Guidance for the use of medicinal cannabis in

Australia – overview (https://www.tga.gov.au/

publication/guidance-use-medicinal-cannabis-

australia-overview).

Based on current evidence, CBD does not

cause psychomotor or cognitive impairment or

strong psychoactive eects. CBD may produce

side eects including sedation or fatigue, which

can be more pronounced at higher doses. CBD

may interact with other prescribed medication,

potentially increasing the risk of driving

impairment. The eects of other cannabinoids

have not been systematically studied.

Managing medicinal cannabis and driving

Strategies to mitigate or manage THC

impairments include a ‘start low, go slow’

approach to treatment and administration during

periods when an individual is unlikely to drive

(e.g. at night before sleep). A period of restricted

or non-driving, generally a minimum of four

weeks, may be considered while adaptation

to medication and treatment outcomes

aredetermined.

Medicinal cannabis (THC and CBD) can

interact with other medications, impairing

the metabolism of other drugs or causing

cumulative eects such as sedation, which can

increase the road safety risk. Alcohol should

be avoided when taking medicinal cannabis

due to the significant additive eects and the

increased risk of having a crash. CBD may eect

the metabolism of certain antiseizure drugs,

elevating plasma levels of other drugs, including

some benzodiazepines.

Assessing fitness to drive

Fitness-to-drive assessments for the underlying

chronic medical condition or disability treated

with medicinal cannabis can be undertaken as

per the applicable standards. The assessment

should consider the nature of the driving task,

impairment of cognitive, visuospatial and

motor control functions from the condition

or medications, and treatment outcomes.

Conditions with specific standards, such as

seizures (Part B section 6.2. Seizures and

epilepsy) or chronic pain (Part B section 5.

Musculoskeletal conditions), may consider

medicinal cannabis under the existing criteria.

Conditions without specific criteria in Part B.

Medical standards may be assessed according

to section 2. Assessing fitness to drive –

generalguidance.

19

PART A. Fitness to drive principles and practices

Medicinal cannabis and commercial

licenceholders

Assessments against the commercial licensing

medical standards are more stringent than the

private standards and reflect increased driver

exposure and the increased risk associated with

motor vehicle crashes involving these vehicles.

Sleep deprivation or fatigue while driving are

common risks among commercial vehicle

drivers. Particular attention should be paid to the

commercial vehicle driving task. Considerations

may include the vehicle type, the nature of

goods transported, the distances and roads

being travelled, the cumulative time driving over

a work period, and whether driving will occur at

night or disrupt normal sleep patterns. Impacts

of driving patterns on dosage requirements

mayalso be relevant.

Medicinal cannabis and drug driving laws

Drug driving and enforcement laws for cannabis

are established through state and territory

legislation and can vary. In general, it is against

the law for a person to drive with any amount

of THC present in their bodily fluids (blood,

saliva or urine). In most states and territories

there are no exceptions to these laws, including

therapeutic use. Tasmanian law provides a

medical defence for driving with the presence of

THC in bodily fluids. The medical defence only

applies if the medicinal cannabis is obtained and

administered in accordance with the Poisons

Act 1971 (Tas). It remains illegal for these patients

to drive if impaired by THC and they must still

comply with directions given by law enforcement

regarding roadside testing.

Drivers prescribed medicinal cannabis in one

jurisdiction may be treated dierently if driving in

another. The individual’s driving needs, including

interstate travel and licensing classes, should

be discussed when considering prescribing

medicinal cannabis, and it is critical to identify if

driving is required as part of their occupation.

Point-of-prescription advice regarding

medicinalcannabis and driving

The implications of drug driving regulations

and THC should be discussed at the point

of prescription and reviewed routinely with

the patient as part of good fitness-to-drive

medical management. In addition to the legal

consequences, there may also be insurance

implications for patients who are convicted of

drug driving oences. CBD is not subject to

these controls and can be used while driving, so

long as treatment is free of side eects or drug

interactions that may cause impairment. Specific

information can be sourced from local driver

licensing authorities, health departments or law

enforcement agencies and should be consulted

alongside the information presented here.

Possible drug-seeking behaviour in those

directly requesting cannabis as an alternative

to, or to supplement, medicinal cannabis should

be kept in mind. Medically prescribed cannabis

is distinct from other sources of cannabis that

people may access for illicit or unregulated

medicinal purposes. These other products are

highly variable in their cannabinoid content and

can significantly increase the road safety risk.

More information can be found in Part B section

9. Substance misuse.

Benzodiazepines

26

Benzodiazepines are well known to increase

the risk of a crash and are found in about 4

per cent of fatalities and 16 per cent of injured

drivers taken to hospital. In many of these cases

benzodiazepines were either abused or used

in combination with other impairing substances.

If a hypnotic is needed, a shorter acting drug is

preferred. Tolerance to the sedative eects of

the longer acting benzodiazepines used to treat

anxiety gradually reduces their adverse impact

on driving skills.

20

Assessing fitness to drive – generalguidance

19

PART A. Fitness to drive principles and practices

Antidepressants

Although antidepressants are one of the more

commonly detected drug groups in fatally

injured drivers, this tends to reflect their wide

use in the community. The ability to impair is

greater with sedating tricyclic antidepressants

(e.g. amitriptyline and dothiepin) than with the

less sedating serotonin and mixed reuptake

inhibitors such as fluoxetine and sertraline.

However, antidepressants can reduce the

psychomotor and cognitive impairment caused

by depression and return mood towards normal.

This can improve driving performance.

Antipsychotics

This diverse class of drugs can improve

performance if substantial psychotic-related