Local development

tax incentives in

northeastern Illinois

Contents

Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 5

Fiscal principles of development incentives ............................................................................. 8

Overall incentive use in northeastern Illinois ......................................................................... 12

How much are incentives used in northeastern Illinois? ............................................................... 12

Which communities are most likely to use incentives? ............................................................... 14

What types of properties are incentivized? ................................................................................. 16

Use of specific incentives ....................................................................................................... 22

Sales tax rebates ........................................................................................................................... 22

Property tax abatements .............................................................................................................. 29

Cook County incentive classification ............................................................................................ 31

Tax increment financing ................................................................................................................ 38

Implementing ON TO 2050 .................................................................................................... 44

Moving forward ..................................................................................................................... 48

Local development

Page 4 of 48 tax incentives

Local development

Page 5 of 48 tax incentives

Introduction

ON TO 2050 — northeastern Illinois’ long-range, comprehensive plan — calls for economic

development that enables more communities to thrive. Greater collaboration to reduce

inequity, leverage our existing assets, and develop talent-driven, export-oriented businesses

can sustain and broaden the region’s prosperity. But current policies often fail to provide

communities with adequate supports to address local needs and align local development with

regional goals. Many local governments are left with few options but to compete for limited

growth through the use of local development tax incentives — offered in pursuit of private

investment, a larger tax base, and jobs.

Incentives are in active use in more than three-quarters of northeastern Illinois’ municipalities

(218 out of 284). Elected officials and economic developers representing several types of taxing

districts turn to these tools in response to competition with other communities, proximity to

lower-tax areas, and substantial variation in development demand across the region. In the face

of revenue and staff constraints, local governments often find that tax incentives are one of the

few accessible, functional tools available to achieve their development goals. They can be

especially useful for promoting aims like infill development or remediating brownfields, where

desired locations have extraordinary costs.

Reflecting national trends, incentive use in the region is expanding.

1

The number of

municipalities in the region with active local incentives has increased by 5 percent since 2013.

Today, local tax incentives impact the revenue-generating capacity of 26 percent of the region’s

commercial and industrial development.

With limited resources, local governments are looking for strategies to effectively meet local

needs. This is particularly true in places that have experienced a marked decline of public and

private investment over decades. Disinvested communities can fall into cycles of slow growth if

a weakening tax base leads to gaps in local tax burdens and the funding available to provide

public services. But incentives often provide more transactional than transformational results,

closing the financial gap for certain developments rather than addressing underlying issues.

Inclusive economic growth depends on the drivers that create real value in our economy, like a

skilled workforce, racial integration and equity, a robust industry mix, the ecosystem to support

new ideas, and the infrastructure to effectively deliver goods and services. The practice of

incentivizing local growth does little to improve these fundamental assets while leaving less

room for collaborative, regional approaches to economic development.

1

Terry F. Buss, “The Effect of State Tax Incentives on Economic Growth and Firm Location Decisions: An Overview of the

Literature,” Economic Development Quarterly 15, no. 1 (February 2001): 92, https://doi.org/10.1177/089124240101500108;

Timothy J. Bartik, “A New Panel Database on Business Incentives for Economic Development Offered by State and Local

Governments in the United States” (Prepared for the Pew Charitable Trusts, 2017), https://research.upjohn.org/reports/225;

Mary Donegan, T. William Lester, and Nichola Lowe, “Striking a Balance: A National Assessment of Economic Development

Incentives,” Working Paper (Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute, 2018), 3, https://doi.org/10.17848/wp18-291.

Local development

Page 6 of 48 tax incentives

Local incentives also present risks. Poorly targeted incentives can lead to high costs, diminishing

returns, and intraregional competition. Despite their widespread use, nearly all academic

evidence shows that incentives produce no significant benefits for long-term regional growth.

While tax incentives can fill certain financial gaps for businesses, recent research estimates that

many agreements make no impact on business location decisions.

2

State and local taxes

represent on average less than 2 percent of total business costs in the U.S., and major expenses

like employee compensation or freight transportation tend to factor more into overall

production costs.

3

Many incentivized developments also fail to generate net fiscal gains or improve the quality of

life for existing local residents.

4

And indirect and longer-term effects of incentive use — like

increased burdens on public infrastructure and intraregional competition on tax rates — can

diminish the benefits of incentivized development, often most of all in communities with the

greatest need for new growth.

Public dataset available

This report is based on a dataset of public records compiled by the Chicago Metropolitan

Agency for Planning (CMAP) from many sources. Alongside this report, CMAP has published

much of the related data for further analysis. Learn more and access the data online on the

CMAP Data Hub at https://datahub.cmap.illinois.gov/dataset/local-tax-incentives-

prevalence-by-municipality.

Decisionmakers should pursue programs, policies, and reforms that equitably support all

communities, improve regional cooperation, and enhance northeastern Illinois’ overall

economic position. CMAP is providing new analysis on the prevalence and distribution of local

development tax incentives to support such structural solutions. Regional and state actions,

including modernizing tax policies and reinvesting in disinvested areas, are needed to enable

more communities to work together and improve local outcomes. This report details four

recommendations defined in ON TO 2050 and connects them to incentive use in the region:

2

Timothy J. Bartik, “‘But For’ Percentages for Economic Development Incentives: What Percentage Estimates Are Plausible

Based on the Research Literature?” (W.E. Upjohn Institute, July 1, 2018), https://doi.org/10.17848/wp18-289; Stephan J Goetz

et al., “Sharing the Gains of Local Economic Growth: Race-to-the-Top versus Race-to-the-Bottom Economic Development,”

Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 29, no. 3 (June 2011): 428–56, https://doi.org/10.1068/c1077r.

3

CMAP analysis of U.S. Internal Revenue Service and the Council on State Taxation data.

4

Cailin Slattery and Owen Zidar, “Evaluating State and Local Business Tax Incentives” (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of

Economic Research, January 2020), https://doi.org/10.3386/w26603; Timothy J. Bartik, “Who Benefits From Economic

Development Incentives? How Incentive Effects on Local Incomes and the Income Distribution Vary with Different Assumptions

about Incentive Policy and the Local Economy,” Technical Report (Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute, March 1, 2018),

https://doi.org/10.17848/tr18-034; Mark D Partridge and Dan S Rickman, “Do We Know Economic Development When We See

It?,” Review of Regional Studies 33 (2003): 17–39.

Local development

Page 7 of 48 tax incentives

Modernize tax policies to sustain communities of all types, including expanding the

state sales tax base, reforming the state’s approach to disbursing state revenues to local

governments, and phasing out the Cook County property tax classification system.

Invest in disinvested areas, including developing creative approaches to supporting

fiscally constrained communities, supporting catalytic public investments, and

developing new programs to enable strategic investments in weak market areas.

Reform incentives for economic development, including encouraging state and local

governments to use incentive best practices like conducting fiscal impact analyses and

establishing terms and conditions that limit taxing districts’ financial liability.

Institute stronger standards for transparency and accountability of incentives,

including requiring consistent and comprehensive public reporting, regular program

audits, and sunset provisions that enable periodic program reevaluation.

Implementing these changes will help make northeastern Illinois a national leader in effective

incentive use while enhancing the region’s economic and fiscal positions. CMAP supports taking

steps that will improve the effectiveness and transparency of local development incentive

programs and encourage more inclusive economic growth. This will, in turn, reduce the need to

incentivize local development.

This report focuses on four types of incentives common in northeastern Illinois: sales tax

rebates, Cook County’s incentive classification system, property tax abatements, and tax

increment financing. These tools are all locally controlled, are enabled by county ordinances

and state law, and have potentially large impacts on community finances.

5

The report begins

with a review of key fiscal principles that underpin local incentive use. The following two

sections review new findings on incentive use in the region, first overall and then by incentive

type. The final section details recommendations and next steps for moving forward.

Guidance for local governments on effective incentive use

Local governments can improve the administration of incentives to enhance their impact.

CMAP’s best practices guide, Improving local development incentives, provides

recommendations and strategies tailored to the needs and experiences of local governments

in northeastern Illinois. Published in September 2020, it identifies principles, strategies, and

practices to better align incentives with local and regional goals, including how to approach

incentive policy design, negotiations with businesses, and program evaluation. Learn more at

https://www.cmap.illinois.gov/programs/innovation/local-incentives.

5

Governments use many tools to influence development outcomes. This report does not address state and federal programs —

such as River Edge Development Zones and federal Opportunity Zones — which are less likely to affect local government

finances and many of which are not administered locally. This report also does not address non-tax local incentives like

streamlined permitting processes, entrepreneurial supports, and job training. Although these are often best practices for

attracting growth, no reporting structures exist to track their use.

Local development

Page 8 of 48 tax incentives

Fiscal principles of development incentives

The actual fiscal impacts of development incentives are complex. Incentives benefit recipients

through lower tax bills, reimbursed tax payments, or publicly financed improvements on the

promise of bringing development and fiscal returns to the community. This trade-off — upfront

financial outlays for the chance at long-term gains — is core to incentives’ logic and structure.

But incentives do not necessarily reduce the revenue that local governments collect, nor are

they guaranteed to enhance local tax bases through greater development. Measuring the

actual impact of incentive use requires both an understanding of how they interact with tax

structures, as well as assumptions about what would have occurred in their absence.

Types of local development tax incentives

Local governments raise revenue from multiple sources, including taxes, user fees, and

intergovernmental transfers. The typical municipality in northeastern Illinois relies on property

taxes for 22.6 percent of their revenues and on state and local sales taxes for 17.5 percent.

6

The box on page 9 describes these two major revenue sources. Each of the four incentives

discussed in this report affects either the amount of revenue collected from the sales or

property tax, or the distribution of tax burden among taxpayers.

Sales tax rebates are revenue-sharing agreements that municipalities or counties form

with businesses and developers to refund a portion of the local share of the state sales

tax, any local option sales tax, or any business district sales tax.

Property tax abatements provide a discount on a property’s final tax bill. Any local

government that extends a property tax can abate its taxes in various contexts.

Incentive classification decreases a property’s assessed value for tax purposes by

lowering its assessment ratio. It is only available in Cook County, which assesses

commercial and industrial property at a higher rate than residential property.

Tax increment financing (TIF) freezes property values within a blighted area or area that

may become blighted, and taxes any new value in that area separately. Property tax

rates applied to increases in value (the increment) generate revenues that can be used

to fund eligible public and private redevelopment projects.

6

CMAP analysis of Illinois Office of the Comptroller data. Analysis includes only general, special revenue, capital project, and

debt service funds.

Local development

Page 9 of 48 tax incentives

Understanding municipal revenues

Sales tax

What is commonly known as the “sales tax” is

actually a complex combination of taxes.

7

In

general, the Illinois state sales tax rate is 6.25

percent for most merchandise and 1 percent

for sales of qualifying food, drugs, and

medical devices. Very few services are taxed

in Illinois. Municipalities receive 1 percentage

point of the 6.25 percent rate on general

merchandise sold within their borders, and

the full amount collected from qualifying

goods. Counties receive a quarter of a

percentage point of the state rate on general

merchandise, and the municipal portion of

either rate in unincorporated areas. Revenues

from remote sales are distributed based on

the point of delivery.

In addition to the state rate, municipalities

and counties can impose taxes on some

general merchandise sales. Excluded are

qualifying food, drugs, and medical devices, as

well as items titled or registered with the

state. For municipalities, these local option

sales taxes range between 0.25 to 2 percent.

Across the region, 67 percent of municipalities

impose this additional tax, most often using a

1 percent rate.

Municipalities can also establish business

development districts (BDDs) in blighted

commercial areas and impose an additional

sales tax to fund redevelopment within the

district. This sales tax can range from 0.25 to

1 percent, with most BDDs in the region

imposing the maximum 1 percent rate.

Property tax

The property tax is a local tax charged on

the estimated value of land and any

permanent improvements (e.g., buildings)

located on it. In Illinois, property tax rates

are recalculated every year to cover each

taxing district’s extension — that is, the

amount of revenue that the district needs

and is authorized to collect.

8

Approximately

1,200 taxing districts — including counties,

townships, municipalities, school districts,

and many others — impose a property tax in

the region, generating $22.8 billion in total

revenue in 2019.

To calculate property taxes in Illinois, county

assessors first estimate the fair market

value of all properties, then apply an

assessment ratio to that market value to

determine each property’s assessed value.

The Illinois Department of Revenue then

calculates an equalization factor for each

county to ensure a consistent ratio and

uniform assessments across the state.

Counties apply their equalization factor to

assessed values to produce an equalized

assessed value (EAV). The sum of EAV in

each taxing district, minus any exemptions,

is the district’s tax base. Tax rates are

calculated by dividing each district’s

extension by their tax base.

County clerks then multiply a property’s

taxable value by each district’s tax rate and

sum the resulting amounts due across taxing

districts, resulting in its final tax bill.

7

In Illinois, “sales tax” generally refers to the following taxes levied on certain goods and services: retailers’ occupation tax, use

tax, service occupation tax, service use tax, and hotel operators’ occupation tax.

8

In Illinois, most property tax extensions are limited by PTELL: the Property Tax Extension Limitation Law. See 35 ILCS 200/18-

185.

Local development

Page 10 of 48 tax incentives

The ‘but for’ test

Individual incentives are often validated and evaluated against a standard referred to as “but

for”: would this or a similar development have occurred but for the incentive given? Meeting

this standard is a statutory requirement of using tax increment financing, business

development districts, and Cook County incentive classification.

For example, a municipality could offer a property tax incentive to a developer to convert an

abandoned facility into a distribution center. In theory, because the facility would not have

contributed much toward the local tax levy without being redeveloped, the initial cost of the

incentive is largely neutral to the taxing districts and other taxpayers, and future economic

gains provide a net fiscal benefit. If the “but for” standard does not hold — if the recipient

would have located in the district anyway or if another developer would have invested in the

facility without assistance — then the incentive only constrains the tax base unnecessarily. This

would likely result in lower tax revenues or higher effective tax rates district-wide.

The “but for” test is difficult to evaluate in practice. Full visibility into a business’ priorities,

resources, and constraints is not always possible, and local government staff cannot know the

alternative futures of any specific parcel with certainty. Careful review of the developer’s

financial reports and the use of third-party advisory services can help. But the standard remains

elusive: recent research suggests that 75 percent or more of incentive use nationally does not

impact firm location decisions.

9

‘But for’ in communities facing market challenges

Market dynamics can substantially impact the incentive negotiation process. When adjacent

communities compete for growth, businesses may use their negotiating position to reap

benefits beyond those necessary to close financial gaps in their development plans. In this case,

passing the “but for” test becomes increasingly about outbidding peers, all of whom want to

generate development. Individual agreements may then meet this standard but nonetheless

remain suboptimal for communities, because more revenues or a larger tax base would have

been possible.

Disinvested communities in our region face particular market challenges. Taxing districts in

these areas often need to impose higher tax rates to balance their financial needs on a smaller

tax base. These conditions are likely to weaken their competitive position when negotiating

with businesses. Disinvested and lower-capacity communities may therefore offer more than

their wealthier peers to attract similar opportunities. Deals that provide greater incentives

relative to their promised benefits can decrease any project’s long-term contribution to the

community. Examples include an increase in incentive value relative to jobs created, the need

for large packages to recruit key community assets like grocery stores, or the inability to

negotiate for the mitigation of any negative side effects of growth. This dynamic hurts the

residents of under-resourced places and reflects larger, structural inequities in the region.

9

Bartik, “‘But For’ Percentages for Economic Development Incentives.”

Local development

Page 11 of 48 tax incentives

Other factors driving fiscal impact

Other factors also contribute to the net fiscal impact of incentive use. Local governments need

to balance potential new revenues with the costs of servicing any new development. Questions

need to be asked on a per-project basis. Local governments should determine whether the

development will raise tax revenues enough to cover new and existing costs without increasing

rates, whether expected spillover effects (like additional local due to new residents and jobs)

will materialize, and whether development will benefit current residents or newcomers.

10

The

impacts are also multijurisdictional: development, especially near municipal borders, may

provide benefits or create costs for neighboring taxing districts.

11

Local governments’ willingness to use incentives to compete within the region can also lead to

diminishing revenues if incentives become increasingly expected and incentive values get larger

over time. Research links this sort of competition to more incentive agreements and lower

public sector revenues,

12

and shows that both the number and average value of incentives have

increased over the last three decades.

13

Some incentives impact the tax base, not revenues

Sales tax rebates and property tax abatements impact final tax revenues: taxing districts that

offer these incentives collect less than those able to attract similar development without

incentives. Tax increment financing and Cook County incentive classification, on the other hand,

impact the property tax base by altering the equalized assessed value (EAV) that districts have

available to tax. Their effects are more complex, determined by how local growth patterns

interact with the structure of the Illinois property tax system.

Incentives that discount a property’s EAV can appear fiscally neutral to the taxing district

because they do not change its tax extensions or reduce tax collections. But actual fiscal

impacts depend on a new development’s net effect on public costs, even if the investment

would not have occurred but for an incentive. If the post-incentive increase in the tax base is

greater than the increase in related service costs, the result is lower property tax rates and bills

district-wide. If the incentive was not necessary to achieve comparable development or if the

cost of new services outpaces the gain in EAV, the result is higher rates and bills in the district.

10

One recent study finds that TIF districts in Illinois, for example, appear to have had a negative impact on job growth: Joshua

Drucker, Geon Kim, and Rachel Weber, “Did Incentives Help Municipalities Recover from the Great Recession? Evidence from

Midwestern Cities,” Growth and Change 50, no. 3 (September 2019): 894–925, https://doi.org/10.1111/grow.12318.

11

For additional analysis, see Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, “Sales Tax Rebates Remain Prevalent in Northeastern

Illinois,” Policy Update, May 2016, https://www.cmap.illinois.gov/updates/all/-/asset_publisher/UIMfSLnFfMB6/content/sales-

tax-rebates-remain-prevalent-in-northeastern-illinois.

12

Stephan J Goetz et al., “Sharing the Gains of Local Economic Growth: Race-to-the-Top versus Race-to-the-Bottom Economic

Development,” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 29, no. 3 (June 2011): 428–56,

https://doi.org/10.1068/c1077r; Jia Wang, “Strategic Interaction and Economic Development Incentives Policy: Evidence from

U.S. States,” Regional Science and Urban Economics 68 (January 2018): 249–59,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2017.11.007.

13

Timothy J. Bartik, Making Sense of Incentives: Taming Business Incentives to Promote Prosperity (W.E. Upjohn Institute,

2019), 7–8, https://doi.org/10.17848/9780880996693; Donegan, Lester, and Lowe, “Striking a Balance,” 3.

Local development

Page 12 of 48 tax incentives

Overall incentive use in northeastern Illinois

Although local development tax incentives are used regularly across northeastern Illinois,

assessing their prevalence is difficult. Different structures, fiscal impacts, and reporting

requirements limit comparison across incentive types. Existing studies tend to focus on a single

type of tax incentive — for example, sales tax rebates or tax increment financing. However,

local governments may use different (or multiple) tools to pursue similar results: separate

incentive negotiations may lead to one community granting a property tax abatement and

another creating a TIF district to attract the same business. Comprehensive analysis can reveal

more about the full extent of incentive use and who uses which tools.

To provide this comprehensive analysis, this report assesses the market value of commercial

and industrial properties with tax revenues reduced, impacted, or restricted by any local

incentive. This approach uses the limited available data about incentives to provide an effective

basis for calculating rates of incentive use.

14

A parcel-level analysis allows for summaries across

any geography, and — because the dollar amount of each incentive deal is usually unavailable

and difficult to compare across incentive types — weighting properties by market value

approximates their relative significance and impact.

15

This approach has limits. First, it does not take into account the total size of incentive packages.

Second, it does not evaluate which incentive agreements in the region adhere to best practices,

such as including job quality, clawback, and reporting provisions. Third, it is not suitable for

making comparisons about the prevalence of TIF versus other incentive types, because the

manner in which TIF affects properties within a district is different from the other incentive

types. Analysis based on actual revenues collected and expended would provide better

comparisons, but the necessary data for this analysis are not consistently available.

How much are incentives used in northeastern Illinois?

Local development tax incentives impact tax revenues from 26.3 percent of commercial and

industrial development in northeastern Illinois, as measured by market value. Estimates are

driven by TIF districts, which are drawn to include 21.7 percent of the region’s commercial and

industrial properties. By comparison, 6.6 percent of business properties are incentivized

through a property tax abatement, Cook County incentive classification, or sales tax rebate.

16

While many communities incentivize a large portion of their commercial and industrial

14

This analysis combines publicly available data, third-party reporting, and information obtained through data use agreements

with other public agencies. Analysis uses data from each county’s assessor to estimate each property’s market value and land

use for tax purposes.

15

The use of market value-weighting assumes that the geographies in question have relatively internally consistent real estate

market dynamics (e.g., that land values are roughly constant within highly infill-supportive areas or within any specific freight

cluster) but does not require consistency across geographies.

16

Throughout this report, the total rate of incentive use is often slightly lower than the sum of its component parts (rates of use

of specific incentives) due to properties that are impacted by multiple types of incentives.

Local development

Page 13 of 48 tax incentives

properties, preferred incentive tools vary by location and reflect both historical development

patterns and current market pressures.

Figure 1 shows that Chicago currently has no sales tax rebates or property tax abatements but

has placed nearly 40 percent of commercial and industrial market value in a TIF district —

substantially more than the average for communities in the rest of the region. Incentive

classification is more prevalent in suburban Cook County (13.5 percent of business property)

than in Chicago (5.6 percent). Both sales tax rebates and property tax abatements are used

more heavily in the collar counties, where large-format, high-sales volume shopping centers

and vehicle dealerships make up a larger portion of total commercial and industrial market

value with incentives. Kendall County, home to the region’s lowest rate of TIF use, has the

highest rates of sales tax rebates and property tax abatements of any county. Property tax

abatements are the least prevalent region-wide, used for only $506 million of property value

(0.3 percent of the regional total).

Figure

1.

I

ncentive use differs across the region, with suburban communities using a wider variety of

incentive types

Share of commercial and

industrial property

market value affected by

local tax

incentives by

location, 2019-20

Note:

Totals reflect properties

that receive multiple incentives

.

Source: CMAP analysis of data

from county assessors, Illinois

Department of Revenue, and

other sources.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

Sales tax rebate Property tax

abatement

Incentive

classification

Tax increment

financing

Any incentive

City of Chicago Suburban Cook County Collar counties

Local development

Page 14 of 48 tax incentives

Which communities are most likely to use incentives?

The vast majority of incentive use occurs within the region’s municipalities, reflecting their

regulatory and practical role in incentive agreements. Over $7 billion of the region’s commercial

and industrial property is in unincorporated areas, but only 0.3 percent of this property is

incentivized, compared to 27.4 percent in villages, towns, and cities. The most common tool in

unincorporated areas is incentive classification, as enabled by Cook County ordinance.

Several factors drive municipalities to use incentives and increase intraregional competition.

State revenue disbursement policies reward municipalities for attracting sales tax-generating

businesses. Public and private disinvestment in older job centers has resulted in a lower tax

base, higher tax rates, and difficulty attracting new development in some communities.

Property classification raises tax rates on commercial and industrial property in some areas of

Cook County relative to neighboring counties. And communities near Indiana and Wisconsin

face competition across state lines.

Of the 218 municipalities in the region that use incentives, the rate of incentivization ranges

from less than 1 percent of commercial and industrial market value up to 100 percent. Figure 2

shows that 29 communities incentivize more than 60 percent of their commercial and industrial

property; an additional 40 incentivize between 40 and 60 percent. Significant incentive use

appears throughout the region, but it is most common in south and west Cook County.

Greater use of incentives is associated with multiple indicators of economic disadvantage and

vulnerability. Figure 3 shows that as the rate of incentive use rises, median household income

and property tax base per capita decrease on average. Meanwhile, the percent of residents

living in communities with high concentrations of people of color with low income tend to

increase.

17

For example, only 7 of the 69 municipalities with over 40 percent incentivization

have median household incomes over $100,000, compared to 74 of the 213 municipalities with

a lower rate of incentive use. Although there is substantial variation across communities, these

findings suggest that the use of development incentives — and the negative impacts of long-

term reliance on them to achieve growth — is concentrated among lower-capacity and lower-

tax-base communities of color, where they may be used to offset structural challenges.

17

Measured using CMAP’s economically disconnected areas, an ON TO 2050 analysis that identifies census tracts with a higher

concentration of people of color with low income or non-English speakers with low income. See page 18 for more details about

this data.

Local development

Page 15 of 48 tax incentives

Figure

2.

The prevalence of

local tax incentives varies by municipality. Incentives impact a smaller

proportion of property in collar county communities, with some exceptions.

Local development

Page 16 of 48 tax incentives

Figure

3.

Higher incentive use is more prevalent in communities with lower incomes and larger

concentrations of residents of color

with low income

Average characteristics

of municipalities by

share of commercial

and industrial

property

market value affected

by local tax incentives,

2019

Note:

Analysis includes local

sales tax rebates, property tax

abatements, Cook County

incentive classification, and

tax

i

ncrement financing districts.

Averages are weighted by

population.

Economically

disconnected areas

are census

tracts with large concentrations

of residents of color

with low

income

and populations with

limited English proficiency

.

Source: CMAP analysis of data

from county assessors, Illinois

Department of Revenue, and

other sources.

What types of properties are incentivized?

Using incentives to encourage growth in targeted geographies — especially economically

distressed areas — may be a bright spot for incentive use.

18

ON TO 2050 calls for focusing

redevelopment in infill-supportive areas; in economically disconnected and disinvested areas;

and near existing freight assets. The plan identifies geographies to support these goals. This

section analyzes incentive use in each of these three areas. Figure 4 shows the distribution of

infill supportiveness and economically disconnected and disinvested areas, while Figure 7 (page

21) identifies the region’s six freight clusters.

18

Bartik, “Who Benefits From Economic Development Incentives?”; Timothy J. Bartik, “Should Place-Based Jobs Policies Be

Used to Help Distressed Communities?,” Working Paper (Kalamazoo, MI: Upjohn Institute, August 1, 2019),

https://research.upjohn.org/up_workingpapers/308/; Joseph Parilla and Sifan Liu, “Examining the Local Value of Economic

Development Incentives: Evidence from Four U.S. Cities” (Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings, 2018),

https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/report_examining-the-local-value-of-economic-development-

incentives_brookings-metro_march-2018.pdf.

$0 $20 $40 $60 $80 $100 $120 $140

No incentives

Under 39.9%

40.0% - 59.9%

Over 60.0%

Thousands of dollars

Median household income Property tax base per capita

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70%

No incentives

Under 39.9%

40.0% - 59.9%

Over 60.0%

Share of population in economically disconnected areas

Local development

Page 17 of 48 tax incentives

Infill supportiveness

Infill development is growth that occurs in areas already serviced by existing infrastructure, like

roads, water mains, and sewers. The construction and maintenance of this infrastructure are a

major expense for municipalities, and growth that requires new facilities is more likely to

generate ongoing future costs. Infill development can therefore generate higher net fiscal

benefits than projects in undeveloped areas.

19

Additionally, increased density from infill can

help to promote transit ridership, provide residents better access to jobs and services, and

reinvigorate older commercial corridors and residential neighborhoods.

20

In preparing ON TO

2050, CMAP conducted the baseline assessment of infill supportiveness shown in Figure 4,

placing every part of the region on a three-tier scale from minimally to highly supportive. As the

necessary infrastructure is built, development in areas that had less access to existing

infrastructure, housing, and jobs in 2000 is likely to contribute to ongoing new costs.

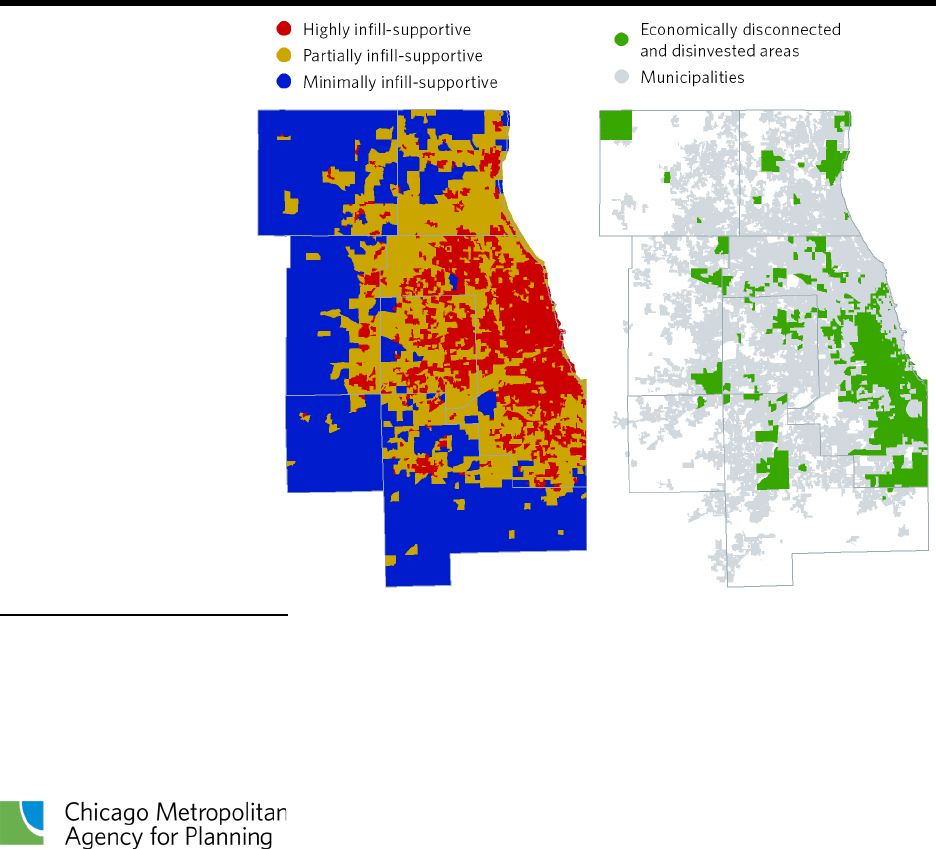

Figure

4.

Two g

eographic analyses completed for ON TO 2050 provide helpful bases for evaluating the

spatial

targeting of incentives

Infill supportiveness

and economically

disconnected

and

disinvested areas,

developed

for ON TO

2050

Note: Infill supportiveness

is a

baseline measure of

locations

with

sufficient infrastructure

like

roads and water systems in

2000

to support development.

Economically disconnected

areas are census tracts

that had

large concentrations of

residents of color

with low

income

in 2014. Disinvested

areas

are non-residential census

tracts that have experienced

declines of business investment

between

1970 and 2015. See

ON TO 2050 for additional

details.

19

Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, “Fiscal and Economic Impact Analysis of Local Development Decisions,” January

2014, https://www.cmap.illinois.gov/documents/10180/82875/Fiscal+Econ+Impacts+Dev+FINAL.pdf.

20

Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, “Reinvestment and Infill,” ON TO 2050 Strategy Paper, June 2017,

https://www.cmap.illinois.gov/documents/10180/517111/Reinvestment+and+Infill+Strategy+Paper/f075aca4-49d1-450a-9af5-

097bfdb12ac4.

Local development

Page 18 of 48 tax incentives

Figure 5 shows that incentive use is most prevalent in highly infill-supportive areas, with 31

percent of commercial and industrial market value impacted by at least one incentive type.

However, over 16 percent of development in minimally infill-supportive areas is also

incentivized. New construction near the region’s edge may be the right fit for certain growth

and may necessitate incentives due to site-specific challenges. But the use of tax incentives in

these areas may also contribute to development patterns that do not achieve regional goals.

Better economic development practices can help to reduce the climate impacts and financial

costs of transportation and conserve lands for critical agricultural and ecosystem services.

The prevalence of specific incentive tools varies substantially across these three tiers. Figure 5

shows that tax increment financing is the most common incentive tool in highly infill-supportive

areas, while other tools are more common in less developed parts of the region. In particular,

property tax abatements, which are relatively non-existent closer to the region’s core, are

much more common in areas identified as the least supportive of redevelopment and infill.

21

Figure

5.

Incentives are more prevalent in infill

-supportive areas near the region’s historic core, but a

sizeable amount of development in minimally

infill-supportive areas is incentivized as well

Share of total

commercial and

industrial property

market value affected

by local tax incentives,

by levels of infill

supportiveness,

2019-20

Note:

Totals reflect properties

that receive multiple

incentives.

Source: CMAP analysis of data

from county assessors, Illinois

Department of Revenue, and

other sources.

21

This report generally refrains from comparing actual incentivized market value across geographies, because market dynamics

and inequities in the appraisal industry contribute to substantially different valuations of property across the region. However,

more than twice as much commercial and industrial property (as measured by market value) in minimally infill-supportive areas

receives a property tax abatement than in partially and highly supportive areas combined, despite the presumption that the

value of like property decreases with greater distance from other dense existing development.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

Sales tax rebate Property tax

abatement

Incentive

classification

Tax increment

financing

Any incentive

Highly supportive Partially supportive Minimally supportive

Local development

Page 19 of 48 tax incentives

Economically disconnected and disinvested areas

CMAP has defined economically disconnected areas (EDAs) and disinvested areas (DAs), where

local and state governments should concentrate investment to address the needs of vulnerable

populations and offset declines over time.

22

EDAs and DAs often face particular market

challenges that limit developer interest, including a high number of brownfield and dilapidated

properties. Targeted incentives can be an effective tool to close genuine neighborhood- and

property-specific financing gaps related to these issues.

Figure 6 shows that incentives are approximately twice as prevalent in EDAs and DAs as in the

rest of the region. This variation is driven by Chicago and suburban Cook County’s respective

use of tax increment financing and incentive classification. Both incentive types are about twice

as prevalent in these communities as in other, more advantaged areas. Incentive use is lower in

EDAs and DAs across the collar counties. Sales tax rebates are notably less present in EDAs and

DAs, where developers may overlook local purchasing power and where there has been less

retail investment historically.

Figure

6.

Local tax i

ncentives, particularly tax increment financing and incentive classification, are used

more frequently in economically disconnected and disinvested areas

Share of total

commercial and

industrial property

value affected by

local

tax

incentives in

economically

disconnected and

disinvested areas, 2019

-

20

Note:

Totals reflect properties

that receive multiple incentives

.

Source: CMAP analysis of data

from county assessors, Illinois

Department of Revenue, and

other sources

.

22

Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, “Economically Disconnected and Disinvested Areas,” ON TO 2050, 2018,

https://www.cmap.illinois.gov/2050/maps/eda.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

Sales tax rebate Property tax

abatement

Incentive

classification

Tax increment

financing

Any incentive

Economically disconnected and disinvested areas Other areas

Local development

Page 20 of 48 tax incentives

More contextual information about specific businesses and developments is needed to fully

evaluate the impacts of incentive use in vulnerable areas.

23

These patterns point to both the

challenges of revitalizing legacy commercial corridors and historic job centers, as well as the

need for structural reforms to support reinvestment. CMAP supports the strategic use of

incentives in these areas. Agreements should reward the creation of high-quality jobs and

target businesses prepared to be effective community partners or provide important local

services. But, as discussed on page 10, the negative consequences of widespread use of local

incentives can limit taxing districts’ long-term capacity to generate revenue. Other business

supports can pursue these goals without relying on the loss or redistribution of local revenues.

Freight clusters

Northeastern Illinois is the nation’s preeminent intermodal freight hub, with 10 interstate

highways, six of the seven Class I railroads, the top international air cargo hub by value in North

America, and the only direct maritime connection between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi

River network. Freight-reliant firms tend to co-locate around shared resources, and although

industrial lands with existing access to freight infrastructure are among the region’s most

significant assets, evolving economies and aging or outdated infrastructure create barriers to

their effective ongoing use.

24

Enhancing the competitiveness of the region’s freight network —

including bolstering productivity and business activity on freight-supportive land — is an

important regional goal. ON TO 2050 identifies six freight clusters to help direct strategic

investment in the freight network.

Figure 7 illustrates incentive use across these freight clusters. Unlike most of the other analyses

in this report, this map shows industrial property only. Industrial development in the freight

clusters outside of Cook County is between 10 and 20 percent incentivized, a rate much lower

than in clusters within Cook County. The heavy use of incentives in the core/Midway and south

Cook County freight clusters (92.5 and 89.1 percent, respectively) may reflect the area’s

structural challenges, such as higher tax rates, expensive redevelopment costs, or freight assets

in need of upgrades.

25

The use of fiscally prudent and well-structured incentives can help to

encourage investments in key components of the freight network, concentrate related

development near existing facilities, and mitigate the negative impacts of freight movement on

vulnerable populations. This analysis does not consider whether the incentives used in freight

clusters meet these goals or were necessary to promote development.

23

For example, incentivizing development in EDA/DA areas can revitalize older commercial and industrial corridors, provide

important amenities to neighborhoods where they are lacking, and create new employment opportunities proximate to

communities with higher-than-average unemployment and lower-than-average transit connectivity. On the other hand, new

development may also harm the communities in which they locate: some commercial and industrial growth may create new

sources of pollution and congestion, adding to existing environmental justice concerns; create jobs that are unsafe or do not

provide living wages or access to professional growth; or sell products that do not improve existing residents’ quality of life.

24

Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, “Local Freight Clusters and Bottlenecks,” ON TO 2050, 2018,

https://www.cmap.illinois.gov/2050/maps/freight.

25

Industrial development in the Greater O’Hare freight cluster, located primarily in Cook and DuPage counties, is 42.1 percent

incentivized. Industrial development in the north Chicagoland, Will County, and Fox River Valley clusters are 19.7, 13.3, and

10.1 incentivized, respectively.

Local development

Page 21 of 48 tax incentives

Figure

7.

I

ncentive use for industrial development in freight clusters is greatest in legacy industrial areas

near the region’s core with existing access to freight facilities

Local development

Page 22 of 48 tax incentives

Use of specific incentives

Although it is important to assess the overall prevalence of local development incentives, each

incentive tool is enabled by distinct legislation, enacted in a specific manner, and unique in how

it impacts taxation. Different data are available for analysis due to the nature and structure of

different incentive types, as well as their disclosure requirements. This section documents

specific findings related to the use, context, and prevalence of each incentive type CMAP

studies: sales tax rebates, property tax abatements, Cook County incentive classification, and

tax increment financing.

Sales tax rebates

In Illinois, sales of most tangible goods are subject to state and local sales taxes, and part of the

revenue is disbursed to local governments. This structure has given rise to a development

incentive called a sales tax rebate, in which local governments are authorized to share a portion

of the sales tax revenue generated by a development back to individual businesses. There are

327 sales tax rebates currently active in northeastern Illinois.

Municipalities and counties can sign sales tax rebate agreements with retailers or developers.

26

Rebates can affect revenues from three categories of sales taxes: the local government’s share

of the state sales tax, any local option sales tax imposed by the county or municipality, and any

additional sales tax imposed in a business district (see box on page 9 for more information on

sales taxes). Without sufficient revenue options, some local governments use these incentives

to pursue sales tax-generating development to increase the total revenue they can collect. As a

result, these rebates often target high-value retailers, such as vehicle dealerships.

Public Act 97-0976 and the lack of information on sales tax rebate agreements

In August 2012, Illinois enacted Public Act 97-0976, which requires municipalities and

counties to report information on sales tax agreements to the Illinois Department of Revenue

within 30 days of execution. This includes the business location, the manner in which the

rebate amount will be determined, and the duration of the agreement, as well as a copy of

the agreement. Despite these requirements, the resulting database is inconsistent and

incomplete. Some agreements are missing entirely from the database. Other key details —

like total sales figures, the sales tax amount collected, and the final revenue amount rebated

— are redacted and exempt from the other public disclosure and transparency laws. Further

reforms are needed to ensure residents and researchers can access the data required to

accurately assess or evaluate sales tax rebates. More information on local governments’

reporting requirements is available at:

https://www2.illinois.gov/rev/questionsandanswers/pages/rebatesharing.aspx.

26

Illinois Municipal Code, 65 ILCS 5/8-11-21; Counties Code, 55 ILCS 5/5-1014.3

Local development

Page 23 of 48 tax incentives

Sales tax rebates use a wide range of terms to obligate funds

The region’s 327 active sales tax rebate agreements are located in 123 municipalities across

northeastern Illinois, according to data provided by municipalities to the Illinois Department of

Revenue (IDOR).

27

Around half of these records (180) have a maximum rebate amount listed in

the database or, in some cases, CMAP knew the maximum through past research. If every

business receives their maximum possible rebate, $447 million could be paid over the life of

these agreements. But actual totals could well exceed these estimates: 147 rebates either have

a maximum that was redacted or unreported in the IDOR database or have no maximum at all.

At least 10 municipalities have active agreements totaling more than $10 million, and 36 have

an agreement that will be in effect for more than 20 years with no known maximum.

The use of sales tax rebates has declined slightly in recent years, with some communities

foregoing new agreements as others have expanded their use. CMAP last analyzed the IDOR

database in 2015 and found 359 agreements across 132 local governments, with reported

maximums totaling $495.9 million.

28

Among the 58 municipalities in the region that executed

new agreements since 2015, three-quarters already had others in effect. By comparison, 24

local governments allowed all their rebates to expire without instituting new ones.

Although the terms can range widely, the typical sales tax rebate returns 50 percent of local

disbursements from the state’s sales taxes for 15 years or up to a specified maximum amount.

Although the lack of consistent public information makes it difficult to characterize their use in

great detail, available data do reveal a number of findings:

How long are the rebates available? All rebates specify a duration, which ranges widely

from two to 100 years. Three-quarters of agreements (242) have durations between 10

and 20 years, with 53 lasting more than 20 years.

Which taxes are rebated? The most common structure is to refund only revenues from

the local allocation of the state sales tax (83 agreements). Figure 8 shows that 63

agreements rebate a portion of the local option sales tax, either instead of or in addition

to those on the state taxes. This includes 19 records of municipalities committing to

rebate revenues from a business development district, as discussed later in this section.

However, 181 records in the IDOR database do not specify which tax will be rebated.

27

Analysis is based on IDOR data retrieved in November 2020, review of news articles about developments, and other

independent research. Analysis excludes sales tax sharing agreements between local governments.

28

Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, “Sales Tax Rebates Remain Prevalent in Northeastern Illinois.”

Local development

Page 24 of 48 tax incentives

0 30 60 90 120 150 180

Local allocation of state sales tax Both state and local sales taxes

Local option sales tax Business district sales tax with other sources

No information

Figure

8.

Most sales tax rebate agreements share the municipality’s allocation of the state sales tax,

sometimes along with other taxes

Number of sales tax

rebate agreements by

type of tax

revenue

rebated, 2020

Note: A

ll agreements that

rebate business district sales

taxes also rebate

state or local

sales taxes.

Source: CMAP analysis of Illinois

Department of Revenue data.

How are the rebate amounts determined? In additional to specified maximums, slightly

over one-third of agreements (121) include minimum sales thresholds, where the rebate

does not begin until the local government first receives a certain amount of revenue.

Between any thresholds and maximums, local governments rebate anywhere from 25 to

100 percent of the sales tax subject to the agreement. Most agreements (144) offer 50

percent of taxes collected, while 101 agreements rebate more than half, including 27

that rebate all eligible taxes after any thresholds. Thirty records do not specify the

proportion rebated.

How many rebates include maximums? Because incentives are meant to close gaps in

developer financing, it is a best practice to cap rebates once the business has recouped

a set dollar amount. Figure 9 shows that 210 agreements include maximum rebate caps,

30 of which are redacted. Maximums range from $48,000 to $30 million, with an

average rebate of $2.5 million.

The benefits and costs of sales tax rebate agreements depend heavily on these terms. Like

other incentive types, sales tax rebates are tax expenditures — they effectively lower tax

revenues rather than increase public spending. Nonetheless, they are direct financial outlays to

private businesses and developers. Agreements with large terms or no maximum rebate

commit communities to providing funds that could reach well beyond those offered through

other incentive types.

Local development

Page 25 of 48 tax incentives

Figure

9.

Rebate maximums

— which average $2.5 million — limit local governments’ obligations to

refund sales tax revenue to businesses if their total sales rise

Maximum rebate

amounts of active sales

tax

rebate agreements

in

northeastern Illinois,

2020

Note: Analysis excludes 117

agreements where data

reported to

the Illinois

D

epartment of Revenue (IDOR)

mak

e no mention of a

maximum rebate and research

using other sources did not

reveal one. These rebates could

have no reba

te cap or caps that

are unreported.

Source:

CMAP analysis of IDOR

data

and other sources.

State tax structure encourages sales tax rebates for retail

The structure of Illinois’ tax and revenue disbursement system encourages communities to

pursue specific types of commercial development for fiscal gain. Municipalities in the region

collected $2.3 billion in sales tax revenue in fiscal year 2019, about 17.5 percent of all municipal

revenues.

29

Local governments in Illinois do not have the authority to impose a local income

tax, and Illinois’ narrow sales tax base is focused on tangible goods and few services, which is

out of sync with increasing market demand for consumer services.

30

Together, these issues

leave many municipalities — especially communities without significant sales tax-generating

development, and those with weak property values and already high property tax burdens —

with few stable options for gathering revenue.

31

29

CMAP analysis of Illinois Office of the Comptroller data. Analysis includes only general, special revenue, capital project, and

debt service funds.

30

Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, “The Benefits of Adding More Services to Illinois’ Sales Tax Base,” Policy Update,

March 2019, https://www.cmap.illinois.gov/updates/all/-/asset_publisher/UIMfSLnFfMB6/content/the-benefits-of-adding-

more-services-to-illinois-sales-tax-base.

31

Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, “Tax Policies and Land Use Trends,” ON TO 2050 Strategy Paper, March 2017,

https://www.cmap.illinois.gov/documents/10180/517351/Tax+Policy+and+Land+Use+strategy+paper/30b90429-1af9-4903-

ad29-b75ed1dc94e0.

0

10

20

30

40

50

$500,000 and

lower

$500,001 -

$1,000,000

$1,000,001 -

$2,000,000

$2,000,001 -

$5,000,000

$5,000,001 -

$30,000,000

Redacted

maximum

Local development

Page 26 of 48 tax incentives

Tax collections from retail businesses and other commercial developments tend to exceed the

cost of servicing them and provide greater fiscal benefits than other property types like office

or industrial sites.

32

Without greater revenue options, state policies reward municipalities for

actively recruiting sales tax-generating businesses within their borders, including by offering

sales tax rebates.

33

This can lead to high levels of retail vacancy and lower overall sales tax

collections due to intraregional competition. Figure 10 shows that municipalities with active

sales tax rebate agreements are typically 10 percentage points more reliant on sales tax

revenues than those without agreements.

The types of businesses receiving sales tax rebates provide further evidence that agreements

tend to promote development that provides more fiscal than economic benefits. Figure 11

indicates that one-third (115) of sales tax rebates go to vehicle dealerships, where high-value

sales can have a large impact on the size of a municipality’s share of state sales tax.

34

Figure

10.

Local governments with active

sales tax rebate agreements are typically 10 percentage points

more reliant on sales tax revenues than those without agreements

Range of municipal

reliance on sales tax

revenue by use of sales

tax rebates, 2019-20

Note: Analysis reflects data

from the

278 of northeastern

Illinois’ 284 municipalities with

sufficient data available.

Source: CMAP analysis of Illinois

Office of the Comptroller and

Illinois Department of Revenue

data.

32

Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, “Fiscal and Economic Impact Analysis of Local Development Decisions.”

33

In 2015, 60 percent of active rebates in suburban areas were given to developments located on or near a municipal border,

compared to 47 percent of all retail businesses. Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, “Sales Tax Rebates Remain

Prevalent in Northeastern Illinois.”

34

Illinois statute does not enable local option sales taxes on titled or registered purchases, so competition for vehicle

dealerships only impacts disbursements of the state sales tax to municipalities. Local governments can implement a use tax on

titled purchases, but this tax is collected based on the purchaser’s home address, not purchase location.

72.6%

62.4%

19.8%

32.1%

7.1%

16.5%

12.4%

22.2%

0%

25%

50%

75%

No active agreements Active agreements

How to read this chart

Maximum

75th percentile

Median

25th percentile

Minimum

Local development

Page 27 of 48 tax incentives

Another 171 rebates (more than half) are awarded to retail establishments like shopping

centers, gas stations, grocery stores, drug stores, and restaurants. Rebates with the highest

maximums also tend to subsidize vehicle dealerships or entire shopping centers.

Although sales tax-generating businesses like grocery or hardware stores can offer important

local amenities, those businesses would mostly exist in the area regardless of incentives

because residents buy these products locally. Municipalities offer sales tax rebates intending to

impact which local government within a market area can collect sales taxes, but not whether

the amenities and tax revenue will exist in that area.

35

These businesses also provide smaller

economic spillovers — such as increased local spending or hires that result from new business

activity — than other firms, like those in manufacturing, transportation and logistics, or

professional services. For example, manufacturers in northeastern Illinois provide an average

wage ($79,200) nearly double that of retailers ($38,500) and regularly source materials and

component parts within the region, helping to localize direct and indirect spending.

36

Figure

11.

Sales tax rebates are

principally awarded to retail and vehicle dealerships

Number of active sales

tax

rebate agreements

by type of business or

development, 2020

Source: CMAP analysis of Illinois

Department of Revenue data

and other sources.

These data show how sales tax-driven economic development can drive diminishing returns

unless they are carefully targeted. The increasing use of sales tax rebates may benefit specific

businesses without providing net benefits to the region or its residents. This happens when

rebates reduce tax revenues, when intraregional competition undermines the apparent fiscal

35

Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, “Examination of Local Economic Development Incentives in Northeastern Illinois,”

August 2013, https://www.cmap.illinois.gov/documents/10180/82875/FY14-

0009+LOCAL+ECONOMIC+INCENTIVES+REPORT.pdf.

36

CMAP analysis of Economic Modeling Specialists International data (Emsi 2021.2).

Vehicle

dealerships

115

Sales and

distribution offices

33

Other

8

Retail

171

Local development

Page 28 of 48 tax incentives

benefits to municipalities with retail development, and when recipients would have located in

the area anyway due to existing market factors.

Sales tax rebates also operate in business development districts

State statute authorizes municipalities to designate business development districts (BDDs),

impose additional sales taxes within them, and rebate the collected tax, among other eligible

uses. Per statute, rebates should reimburse project costs that conform to the BDD’s adopted

redevelopment plan.

37

Twelve municipalities have reported 19 rebate agreements to the Illinois

Department of Revenue (IDOR) that draw from business district sales taxes.

Sales tax rebates in BDDs generally reflect standard sales tax agreements in terms of durations,

sales thresholds, and caps. But they also differ in important ways. They are more likely to return

all of the applicable sales tax revenues that a recipient originates — 12 of the 19 agreements

rebate 90 to 100 percent — and are more likely to draw on multiple revenue sources to pay

businesses or developers. Agreements in BDDs also target more substantial redevelopment

projects: half of the reported agreements are for large shopping centers or adjacent gas

stations, drug stores, and large-format grocery stores.

How prevalent are business development districts?

Use of business district sales taxes has grown rapidly over the past decade. Thirty

municipalities in northeastern Illinois collected $10.7 million across 46 districts in fiscal year

2020, tripling the $3.4 million received by just nine municipalities in fiscal year 2012. This can

be a source of ample revenue over time, with districts in the region averaging around

$229,000 per year since 2007. This could amount to $7 million over their 23-year allowed

lifespan, if revenues grew 2.5 percent annually.

37

BDDs are similar in statutory intent and function to tax increment financing districts, with parallel requirements on criteria,

including qualifying blighted areas, preparation of a redevelopment plan, a maximum term of 23 years, and eligible expenses,

among others. But the statutory process to establish a BDD is generally less stringent because it does not affect the collection

or distribution of property taxes, nor the tax base of other units of governments. See 65 ILCS 5/11-74.3 and 74.4.

Local development

Page 29 of 48 tax incentives

Property tax abatements

Any Illinois district that extends a property tax can reduce this tax for certain properties. Most

abatements take a specified percent off the final tax bill for a period of years, with the discount

staying flat over time or decreasing annually. The most common property tax abatements are

statutorily limited to $4 million and 10 years. Abatements are less common than other types of

local incentives in the region.

38

The box below summarizes different types of abatements that

are authorized in the Illinois Property Tax Code.

39

Although municipalities or counties often take a lead in working with businesses and

developers on new economic development projects, individual taxing authorities must approve

property tax abatements. Municipalities often represent a relatively small portion of properties’

overall tax bill, so businesses and developers often solicit abatements from multiple local taxing

districts at once.

Property tax abatement eligibility

State statute enables property tax abatements in various contexts. Property currently eligible

for abatements include:

40

Up to $4 million over 10 years for any commercial or industrial firm’s property. The

abatement period may be renewed if the firm had originally expanded its facility or

increased the number of employees.

Up to $4 million over two years for a business that locates in a facility that was vacant

for at least two years.

Up to $12 million over 20 years for commercial or industrial development of at least

500 acres or those of at least 225 acres designated as a high impact business.

Any amount over 10 years for a property located in a business corridor created by an

intergovernmental agreement between two adjoining disadvantaged municipalities.

Any amount over 10 to 15 years for qualifying facilities owned by an electric vehicle,

vehicle component, or vehicle power supply manufacturer and subject to a state

incentive agreement.

38

Municipalities in Cook County tend to use incentive classes as an alternative way to achieve a similar outcome for recipients

(lower property tax bills) with significantly different fiscal implications for local governments.

39

See 35 ILCS 200/18-165, 35 ILCS 200/18-184.5, 35 ILCS 200/18/184.10, and Illinois Public Act 102-0669.

40

Some abatements can be granted under other circumstances, including horse and auto racing facilities; academic and

research institutes; affordable senior and low-income housing; new single-family residential buildings in an “area of urban

decay”; properties in Enterprise Zones or River Edge Redevelopment Zones; and properties subject to annexation. Authority to

Local development

Page 30 of 48 tax incentives

Abatements are concentrated in a few communities, primarily for

industrial uses

In 2019, 48 businesses and developers received just over $5 million in total abatements for the

year. The typical agreement includes a 50 percent reduction in annual property taxes, with

many abating as much as 95 to 100 percent. On average, recipients — most often industrial

properties — paid $104,000 less than they would have in 2019 due to the incentive, although

the actual abated amount ranges from a few hundred dollars to $625,000 for the year.

41

Some

agreements also specify commitments in exchange for the abatements, such as minimum

capital investments, new or retained jobs, or square footage of completed improvements.

Industrial properties represent more than 81 percent of the market value of all properties with

abatements but 55 percent of the total abated tax payments. Non-industrial abatements

accounted for fewer agreements (20 out of 48), but the abatement amount tended to be higher

on average. Other types of properties with abatements included nursing home and senior

facilities, retail establishments, movie theaters, and hotels.

Although property tax abatements are not particularly prevalent in the region, their use tends

to be concentrated in communities that favor them over other incentive types. These

agreements are present in just 22 municipalities within the region, and four municipalities

account for nearly half of the 48 agreements. Country Club Hills, Joliet, University Park, and

Wilmington together provided 21 abatements totaling $1.9 million in 2019.

Although municipalities typically lead the incentive negotiation process, they are only one of

many taxing districts with a property tax levy, and larger incentives can be assembled by

arranging simultaneous rebates from multiple districts. Twenty of the 48 abatement incentives

include abatements from multiple districts. These incentives are on average more than three

times the size of single-district abatements.

Because school districts account for the largest share of the overall property tax extension in

the region, they can often offer the largest property tax abatements. School districts are

sought-after partners in abatement negotiations: all but one multi-district abatement includes

at least one elementary, unit, or high school district, and over 20 percent of single-district

agreements were abatements made by school districts. Of the 64 taxing districts with active

abatements in 2019, 28 were school districts compared to 15 municipalities and two counties.

provide abatements to certain corporate headquarters relocating from out of state expired August 1, 2006, but since the

abatement period could last up to 20 years, some may remain active.

41

Small abatements may be a function of development (or reassessment of new development) that has not yet occurred.

Percentage-based property tax abatements — which account for the vast majority of the region’s abatements — become

increasingly valuable as the assessed value of the incentivized property increases.

Local development

Page 31 of 48 tax incentives

Cook County incentive classification

Cook County uses a property assessment approach that differs from the rest of Illinois,

assessing commercial and industrial properties at a higher rate than other property. This system

has led to the practice of designating incentive classifications for certain eligible properties to

provide reduced assessment ratios, lower taxable values, and smaller tax bills for a fixed period

of time. The use of incentive classification is significant and expanding in Cook County. This tool

is used primarily to spur investment in industrial lands and disinvested communities.

Classification drives the use of incentives to reduce tax burdens

Property classification in Cook County results in larger tax bills for businesses and smaller bills

for owners of residential property. The extent of this shift varies across the county based on the

breakdown in each taxing district between commercial or industrial property value and other

property value, like residential; in many communities, the impact can be significant.

42

In parts

of suburban Cook County, commercial and industrial properties experience substantially higher

effective tax rates — usually greater than 5 percent and sometimes above 10 percent — than

residential properties, which typically have rates below 5 percent.

43

This burden shift does not

exist in the collar counties, driving a differential that can adversely affect businesses.

The substantial prevalence of incentive classification reflects the challenges created by the

county’s approach to property assessment. Higher assessment ratios — and higher effective tax

rates — for businesses drive the use of incentive classes to support certain commercial and

industrial properties. Doing so counteracts the systemic challenges unevenly and inconsistently:

the select commercial and industrial properties with incentive classification can contribute to

an overall decrease in the local tax base, resulting in higher tax rates district-wide and a shift in

tax burden onto other property owners. These rate changes will vary based on the land use

makeup of the district and the percentage of properties receiving incentive classification.

Industrial development receives most incentive classification

In 2019, 8.8 percent of the county’s total market value in commercial and industrial properties

received a Class 6b, 7a, 7b, 8, or C incentive classification.

44

Most municipalities (95 out of 134

total), as well as portions of unincorporated Cook County, use these tools. The practice has