The Mandarin Model of Growth

Wei Xiong

y

September 2019

Abstract

This paper expands a standard growth model to analyze the roles played by

the government system in the Chinese economy, with a particular focus to include

the agency problem between the central and local governments. The economic

tournament among local governors creates career incentives for them to develop

local economies. The powerful incentives also lead to short-termist behaviors,

which explain a series of challenges that confront the Chinese economy, such as

overleverage through shadow banking and unreliable economic statistics.

I am grateful to Jianjun Miao, Yingyi Qian, Tao Zha, Li-An Zhou and seminar participants at the 2018

Hong Kong-Shenzhen Summer Finance Conference, the 2018 NBER Chinese Economy Meeting, the 2018

SAIF Symposium on Frontiers of Macroeconomics, the 2019 IMF Conference, Princeton, SWUFE and UIBE

for helpful discussions and comments, to Lunyang Huang and Chang Liu for able research assistance, and in

particular to M ichael Song for highly constructive suggestions.

y

After four decades of rapid growth, the Chinese economy has slowed down in the recent

years with a wide range of concerns about China’s …nancial stability.

1

To systematically

analyze these concerns requires an economic framework that accounts for China’s unique

economic structure. Despite that China’s highly successful economic reforms in the past

forty years have made it the second largest economy in the world, its economic structure

and policy making processes are still distinctively di¤erent from a typical western economy,

such as the U.S. These di¤erences dictate that China faces di¤erent risks and its p olicy

makers may adopt di¤erent policy responses to potential risks. This paper aims to expand

a standard macroeconomic framework to account for some of the di¤erences.

A large strand of the literature emphasizes that career incentives created by the economic

tournament among regional government o¢ cials as a key mechanism to explain China’s rapid

economic growth, e.g., Qian and Roland (1998), Maskin, Qian and Xu (2000), Blanchard

and Shleifer (2001), and Li and Zhou (2005). As nicely summarized by Xu (2011) and

Qian (2017), China has a complex government system with the central government working

along with regional governments at several levels: province, city, county, and township.

Regional governments are major players in China’s economic development. First, regional

governments carry out over 70% of …scal spending in China, and they are responsible for

developing economic institutions and infrastructure at the regional levels, such as opening up

new markets and constructing roads, highways, and airports. Second, despite their autonomy

in economic and …scal issues, regional government leaders are appointed by the central

government, rather than being elected by the local electorate. To incentivize regional leaders,

the central government has established a tournament among o¢ cials across regions at the

same level, promoting those achieving fast economic growth and penalizing those with poor

performance. The powerful incentives may lead to not only rapid growth but also short-

termist behaviors of regional governors, which have profound implications about China’s

…nancial stability. A key ongoing concern is related to China’s leverage rising to an alarming

level in recent years. As recognized by Bai, Hsieh and Song (2016) and Chen, He and Liu

(2017), this leverage boom was primarily driven by China’s local governments.

This paper develops an economic framework to analyze a range of short-termist behaviors

induced by the powerful incentives of regional governors. Speci…cally, my framework expands

the growth model of Barro (1990) to incorporate this institutional structure of China’s gov-

1

See Song and Xiong (2018) for a review of these concerns .

1

ernment system. As described in Section 1, the model considers an open economy with a

number of regions. In each region, the representative …rm has a Cobb-Douglas production

function with three factors: labor, capital, and local infrastructure. The …rm hires labor

from local households at a competitive wage and rents capital at a given interest rate from

an open capital market. By creating more infrastructure in the region, the local govern-

ment can boost the productivity of the local …rm. Infrastructure investment thus serves

the key channel for the local government to directly stimulate the local economy. However,

the local government faces a tradeo¤ in allocating its …scal budget into local infrastructure

and consumption by government employees. As the local government do es not internalize

household consumption, it has a tendency to underinvest in infrastructure relative to the

…rst-best benchmark, in which a social planner makes the infrastructure investment decision

to maximize the social welfare of not only government employees but also the households.

This underinvestment problem re‡ects a key agency problem between the central and local

governments, which motivates the central government to establish the economic tournament

among regional governors.

I introduce the economic tournament in Section 2. The central government uses the

output from all regions at the end of each period to jointly assess the ability and determine

career advancement of all regional governors. As more investment on infrastructure improves

regional output, the tournament generates an implicit incentive for each governor to invest in

infrastructure through the “signal-jamming mechanism”coined by Holmstrolm (1982), due

to the inability of the central government to fully separate the contribution of a governor’s

ability and infrastructure investment to the regional output. This incentive serves as a

powerful mechanism to drive China’s economic growth, as discussed above.

More interestingly, the powerful incentives induced by the tournament may also lead local

governments to engage in short-termist behaviors, which help to explain various challenges

that currently confront the Chinese economy. First, despite its advanced information tech-

nology, China still lacks reliable statistics about its economy. As discussed by Chen et al.

(2018), the sum of China’s provincial GDP has been routinely higher than the national GDP

by a substantial amount— around 5 percent— since 2004. This enormous discrepancy cannot

simply be attributed to measurement errors. Instead, it is deeply rooted in the government

bureaucracy, as regional governments can in‡uence regional statistics bureaus, which report

regional economic statistics. In Section 3, I extend the model to capture this phenomenon

2

by making the central government reliant on regional governors to report regional output,

which is, in turn, used to evaluate their performance and to determine the region’s tax

transfer to the central government. Consequently, career concerns motivate each regional

governor to overreport regional output, at the expense of a higher tax transfer to the central

government. This mechanism is similar in spirit to overreporting of earnings by executives

of publicly listed …rms, e.g., Stein (1989).

The tournament among regional governors also helps to explain the rising leverage across

China. To address this issue, I further expand the model in Section 4 to allow each regional

government to use debt …nancing to expand its …scal budget. The regional governor faces an

intertemporal tradeo¤ in using more debt to …nance more infrastructure investment. On one

hand, by taking advantage of a high growth rate of regional productivity, debt bene…ts the

households (a social motive) and boosts the governor’s personal career (a private motive).

On the other hand, it requires a higher debt payment in the next p eriod. While a certain

level of debt is socially bene…cial when the local productivity growth rate is su¢ ciently high,

my model also shows that a governor’s career concerns can lead to overinvestment by using

excessive leverage.

My model also o¤ers an intricate mechanism of spillover of excessive leverage from one

region to other regions. Under the assumption of rational expectations, the central govern-

ment is able to fully anticipate short-termist behaviors of each regional government, such

as output overreporting and excessive use of leverage, and thus insulate the relative per-

formance evaluations of other governors from such behaviors. By adopting a more realistic

assumption that the central government can only realize local governments’short-termist

behaviors with a delay, as consistent with China’s gradualistic approach to economic reform,

Section 5 shows that short-termist behaviors of one governor adversely a¤ect the relative

performance evaluation of other governors, which, in turn, leads to a rat race between the

governors in using leverage.

Overall, this “Mandarin” model is de…ned by two key features of the Chinese economy.

First, the government takes a central role in driving the economy through its active invest-

ment in infrastructure, which can be interpreted more broadly as measures and policies by

the government to stimulate economic development. Second, agency problems in the gov-

ernment system can lead to a rich set of phenomena— not just economic growth propelled

by the tournament among regional governors, but also short-termist behaviors of regional

3

governors that directly a¤ect China’s economic and …nancial stability.

Section 6 provides several stylized facts. In particular, by using local government leverage

reported by the national audit of the Ministry of Finance and provincial GDP overreporting

estimated by Chen et al. (2018), I show that across provinces, there is a positive relation-

ship between GDP overreporting and local government leverage. This curious relationship

suggests that these two types of short-termist behaviors might be driven by the same force,

lending support to a key notion of my model that career incentives lead regional governors

to pursue both GDP overreporting and excessive leverage.

My work builds on the literature that studies China’s institutional reform. Qian and

Roland (1998) model the competition among local governments for mobile production factors

(such as capital and labor) and the central government’s resource allocation, albeit not lo cal

o¢ cials’career incentives, and show that the competition helps harden local governments’

soft budget constraints. Lau, Qian and Roland (2000) analyze the optimality of the dual-

track reform approach adopted by China in allowing private …rms to coexist and compete

with state …rms. The work of Maskin, Qian and Xu (2000) is particularly close to mine as it

justi…es the e¤ectiveness of the tournament competition in motivating local o¢ cials. There

is also substantial empirical evidence showing that local economic performance, such as GDP

growth, is signi…cantly correlated with career incentives of local o¢ cials, e.g., Li and Zhou

(2005) and Yu, Zhou and Zhu (2016). Building on these insights, my model embeds local

governors’career incentives into a macroeconomic framework and expands this literature by

highlighting various short-termist behaviors induced by such incentives.

This unique focus also di¤erentiates my model from other work analyzing China’s macro-

economy. Brandt and Zhu (2000) highlight the government’s commitment to support em-

ployment in ine¢ cient state …rms through money creation as a key driver of in‡ationary

pressure in China. Song, Storesletten and Zilibotti (2011) develop a macroeconomic model

for how …nancial frictions cause banks to favor state …rms and discriminate against more

e¢ cient private …rms, leading to a puzzling observation of a fast-growing country exporting

capital to other countries. Li, Liu and Wang (2015) develop a general equilibrium model to

show how state …rms, despite being less e¢ cient, managed to earn more pro…ts than private

…rms by monopolizing upstream industries and extracting rent from more liberalized down-

stream industries. Hsieh and Klenow (2010) measure misallocation of capital and labor in

China. Young (2003) and Zhu (2012) provide growth accounting of China. Hsieh and Song

4

(2015) analyze the transformation of state …rms during China’s economic reform. Chere-

mukhin et al. (2017) use a neoclassical two-sector growth model with wedges to analyze

growth in China’s pre-reform years in 1953–1978.

1 The Basic Setting

I consider an economy with M regions and in…nitely many periods t = 0; 1; 2::: In each region,

I employ a standard setting of Barro (1990) with infrastructure as public goods provided by

the regional government. In region i (i = 1; :::; M), the local output is determined by the

production of a representative …rm:

Y

it

= A

it

K

it

L

1

it

G

1

it

;

where A

it

is the local productivity, K

it

is the capital used for production, L

it

is the local

labor input. The parameters 2 (0; 1) and 1 are the output shares of capital and

labor, respectively. In this section, I simply assume that the local pro ductivity A

it

in one

region is identically and independently distributed over time, without imposing any structure

on the productivities across regions. From the next section on, I will specify a particular

structure with the local productivity determined by the local governor’s ability and a common

productivity shock that a¤ects the productivities of all regions, in order to analyze the local

governors’career incentives.

The third factor G

it

is infrastructure created by the local government. It serves as a

public good that boosts the local productivity. One may interpret G

it

as electricity, roads,

bridges, ports, and highways.

2

One may also broadly interpret G

it

as other measures and

policies taken by the government to support and stimulate the lo cal market and economy.

As I will show, the …rm chooses capital and labor based on the level of local infrastructure.

G

it

thus serves as a direct channel for government investment to drive the economy. After

accounting for …rms’ capital and labor choices, the regional economy displays a constant

return with respect to G

it

; a feature that resembles the endogenous growth model of Romer

(1986).

2

Bai and Qian (2010) provide a detailed account of China’s development of infrastructure in three sec-

tors: electricity, highways, and railways. Zhang and Barnett (2014) show that infrastructure investment

contributed to nearly 15% of China’s GDP in 2008–2012.

5

1.1 Firms and Households

In each period, the representative …rm in region i …rst observes the current period produc-

tivity A

it

and then hires capital and labor to maximize its pro…t:

max

fK

it

;L

it

g

A

it

K

it

L

1

it

G

1

it

it

L

it

RK

it

;

where

it

is the competitive wage and R is the rental rate of capital, which is equal to the

interest rate. Throughout the paper, I assume that each region has small open economy so

that the …rm in each region can rent capital from the global capital market at an exoge-

nously given interest rate R: Suppose that labor is not mobile and each region has a …xed

labor supply L

it

= 1. Then, the …rst-order condition implies that the competitive wage is

determined by the marginal product of labor:

it

= (1 ) A

it

K

it

G

1

it

: (1)

Equating the marginal product of capital with the rental rate of capital gives the …rm’s

optimal capital:

K

it

=

A

it

R

1=(1)

G

it

; (2)

which depends on the …rm’s productivity, the capital rental rate, and the local infrastructure.

By substituting L

it

and K

it

back to the output and market wage, I have

Y

it

=

R

=(1)

A

1=(1)

it

G

it

: (3)

The …rm’s optimal capital choice and output are both proportional to local infrastructure

G

it

; which is developed by the local government. Thus, by developing local infrastructure,

the local government can directly stimulate …rms to expand their capital investment and raise

the labor wage.

3

Furthermore, the production technology of the local economy is essentially

an AK technology with respect to infrastructure stock G

it

.

In each region, there are overlapping generations of households, as in Diamond (1965).

Each generation of households lives for two periods, and each individual born at t has

identical preferences represented by

ln(C

t

it

) + ln(C

t

it+1

);

3

Allowing labor to be mobile across regions would further amplify the tournament competition among

the regional governors as their infrastructure investment may also attract labor from other regions.

6

where C

t

it

and C

t

it+1

represent consumption chosen by the individual across his lifetime at

t and t + 1. The parameter 2 (0; 1) is the individual’s time discount rate for the next

period’s consumption. This OLG speci…cation with logarithmic utility simpli…es household

decisions, but is inconsequential to our key insight.

Each individual supplies one unit of labor when he is young, i.e., L

it

= 1, at a competitive

wage and divides his wage income between consumption C

t

it

and savings S

t

it

:

C

t

it

+ S

t

it

(1 )

it

L

it

;

where

it

is the competitive wage and is the tax rate on both labor and capital income.

The savings are invested in the capital market at the constant gross interest rate R > 1 for

the next p eriod’s consumption:

C

t

it+1

= (1 ) RS

t

it

:

The standard result for log utility implies that the individual consumes a …xed fraction of

his labor income in the current period and saves the rest for the next perio d:

C

t

it

=

1

1 +

(1 ) (1 )

it

L

it

=

1

1 +

(1 ) (1 )

R

=(1)

A

1=(1)

it

G

it

;

C

t

it+1

=

1 +

R (1 ) (1 )

2

R

=(1)

A

1=(1)

it

G

it

:

1.2 Local Government

I assume that the country adopts a system of …scal federalism. Speci…cally, the local govern-

ment of each region collects tax and uses the tax revenue for developing local infrastructure

and funding its own consumption. For simplicity, this paper ignores the …scal spending of

the central government, as well as other policy interventions of the central government in

the economy.

Tax is collected from labor and capital income at a rate of : Thus, the local government’s

tax revenue in period t is (

it

L

it

+ RK

it

) = Y

it

; which contributes to its budget at the

end of perio d t:

W

it

= Y

it

+ (1

G

) G

it

; (4)

with

G

2 [0; 1] as the depreciation rate of infrastructure and (1

G

) G

it

as the infrastruc-

ture stock after depreciation. As the government employs a large number of employees, a

7

fraction of this budget has to be spent for the bene…t of government employees. Thus, the

local governor needs to allocate the budget between infrastructure for the following p eriod

G

it+1

and consumption by government employees E

G

it

> 0 in the current period:

G

it+1

+ E

G

it

= W

it

: (5)

For simplicity, I ignore other types of government spending. Note that E

G

it

bene…ts govern-

ment employees,

4

but does not directly serve the households. In contrast, the infrastructure

G

it+1

serves the welfare of both government employees and households as it increases the

productivity of the local economy. This budget allocation of the local government between

infrastructure investment and consumption of government employees serves as the key agency

problem in our model.

5

I assume that the local government aims to maximize the following Bellman equation:

V (G

it

; A

it

) = max

G

it+1

E

t

ln

C

t

it

+ ln(C

t1

it

)

+ ln (W

it

G

it+1

) + V (G

it+1

; A

it+1

)

;

(6)

subject to the budget constraint in (5). In this speci…cation, the local government assigns

a weight of 2 [0; 1] to the consumptions of the households and a weight of > 0 to

the consumption of government employee. For comparison, we assume that in the …rst-

best benchmark, which we analyze in the next subsection, household consumption carries a

weight of 1. The expectation operation E

t

[] represents the conditional expectation at time

t after the current-period productivity A

it

and output Y

it

are observed. The government

uses the same discount rate as households. The value function V () captures the welfare

of the households and the government employees from period t onwards, with both G

it

and

A

it

as the state variables to capture the infrastructure level and productivity shock for the

current period. In choosing the current period consumption E

G

it

, the local government faces a

dynamic tradeo¤ as a higher level of E

G

it

reduces the infrastructure level and thus the output

in the following period.

6

4

Note that the government consumption may also include corruption and embezzlement in the government

system.

5

An alternative setting is to introduce an e¤ort choice by the local government, which would also induce

an agency problem between the central and local governments. I prefer the agency problem induced by the

budget allo cation because it allows me to introduce leverage as an additional choice to the local government,

which I will examine later.

6

While the households live for two periods, I assume that the government lives forever in order to highlight

the notion that the bureacracy aims to maximize the welfare of government employees, as opposed to the

social welfare.

8

Note the following remarks on the setting: First, in this section, the government cannot

borrow or save and must spend its budget in each period on either infrastructure investment

or government consumption. I relax this restriction in Sections 4 and 5 by allowing the

government to use debt. Second, the government’s investment decision at time t determines

the level of infrastructure at t + 1. This feature is realistic as infrastructure usually takes

time to build. Third, throughout the paper, I assume that the local government faces a hard

budget constraint and cannot lobby for any additional budget or bailout from the central

government.

7

Fourth, I ignore the multiple layers of subnational governments in China to

focus on the potential distortions induced by the agency problem in one layer.

8

Finally, this

paper simply assumes that the local government can carry out its infrastructure investment,

without introducing state owned enterprises, which are often responsible for infrastructure

investment in practice.

As the governor is constrained from borrowing or saving, he faces an intertemporal trade-

o¤ in allocating his current-period budget on either infrastructure investment or government

consumption. If he allocates more to infrastructure investment (i.e., a higher G

it+1

), the

local output and tax revenue in the next period are higher, trading o¤ less current-period

government consumption. This dynamic tradeo¤serves as the key mechanism throughout the

paper for discussing the career incentives and short-termist behaviors of the local government.

By directly solving the Bellman equation, Proposition 1 summarizes the governor’s optimal

investment rule.

Proposition 1 In each period, the local government allocates a fraction of its budget to local

infrastructure:

G

it+1

=

1

(1 )

+

[Y

it

+ (1

G

) G

it

] :

This simple setting captures a mixed economic structure— the local government drives the

regional economy by building up local infrastructure, while local …rms make capital and labor

choices in response to the government’s infrastructure investment. Thus, by investing more

into local infrastructure, the local government can stimulate more investments from local

…rms. One may broadly interpret infrastructure in this model as including not only physical

7

See Qian and Roland (1998) for a thorough analysis of how …scal competition among local governments

under factor mobility can harden their soft budget constraints.

8

See Li et al. (2017) for a model that speci…cally analyzes distortions in a multi-layered tournament-

based organization. Their analysis illustrates a top-down ampli…cation of economic growth targets along the

jurisdiction levels.

9

infrastructure, such as roads and ports, but also intangible infrastructure such as policies

and systems that local governments develop to improve the local economic and business

environment. Proposition 1 highlights a tension in the infrastructure development. The

fraction the local government assigns its budget to infrastructure

1

(1)

+

is increasing

with but decreasing with . The intuition is simple. As the local government puts a greater

weight on household consumption, it allocates more budget to infrastructure. On the other

hand, a greater weight on consumption of government employees leads to a lower budget

to infrastructure.

1.3 The First-Best Benchmark

Since the local government’s infrastructure choice does not fully account for the welfare of

the households, it may not b e socially optimal. For comparison, I now analyze the …rst-best

benchmark. Speci…cally, I consider a social planner, who aims to maximize the welfare of

the households in addition to that of the government employees. In each period, I let the

social planner, rather than the local government, make the infrastructure decision. Then,

given the infrastructure level, the representative …rm makes its capital and labor choices, as

in the main setting. That is, at time t; the …rm chooses its capital after observing the local

government’s infrastructure choice G

it

and the local productivity A

it

as given in (2), and

o¤ers a competitive wage, as given in (1), so that L

it

= 1: Consequently, the output is given

by (3).

The social planner allocates the aggregate social budget in the local economy

W

planner

it

= Y

it

+ (1

G

) G

it

to the young generation consumption C

t

it

, to the old generation consumption C

t1

it

, to the

government consumption E

G

it

, and to infrastructure G

it+1

:

W

planner

it

= C

t

it

+ C

t1

it

+ E

G

it

+ G

it+1

(7)

to maximize

V

W

planner

it

= max

C

t

it

;C

t1

it

;E

G

it

;G

it+1

E

t

h

ln

C

t

it

+ ln(C

t1

it

) + ln E

G

it

+ V

W

planner

it+1

i

; (8)

subject to the budget constraint in (7). Di¤erent from the objective of the local government,

the planner assigns a weight of 1 to household consumption, rather than .

The following proposition states the result from solving the planner’s Bellman equation:

10

Proposition 2 In the …rst-best benchmark, the social planner allocates a …xed fraction of

the aggregate social budget to infrastructure:

G

it+1

= [Y

it

+ (1

G

) G

it

] :

A comparison of Propositions 1 and 2 shows that the local government underinvests

in infrastructure relative to the …rst-best level if is su¢ ciently small. As & 0, the

local budget to infrastructure goes to G

it+1

= [Y

it

+ (1

G

) G

it

], which is strictly lower

than the …rst-best level. This is because the local government does not fully internalize the

consumption of the households in its infrastructure choice. This underinvestment re‡ects a

fundamental agency problem between the central and local governments.

The central government cannot resolve this underinvestment problem by standard …s-

cal policies. First, as the central government controls taxation, it is tempting to use an

optimal tax rate to solve the underinvestment problem. Comparing Propositions 1 and 2

reveals that optimizing the tax rate cannot lead to the …rst-best outcome. Suppose that the

agency problem is severe with = 0, then G

it+1

= [Y

it

+ (1

G

) G

it

] : In this situation,

setting the tax rate to 100% could lead the local government to choose the …rst-best level

of infrastructure. However, this tax rate is clearly not feasible as it leaves nothing to the

households, and thus cannot be socially optimal.

Second, the central government may choose to subsidize infrastructure investment, for ex-

ample by providing loans at subsidized interest rates to local governments for infrastructure

projects. Such …scal subsidies are able to boost infrastructure investment. However, under-

investment in infrastructure is just one of many possible distortions caused by the agency

problems of local governments. Fiscal subsidies cannot remedy all of such distortions, such

as corruption. Thus, the central government needs to give local governors incentives to do

the right things in numerous decisions they make, which we discuss in the next section.

2 Career Incentives

Di¤erent from the typical federal government system in other countries, regional governors

in China are appointed by the central government rather than elected by a local electorate.

As eloquently summarized by Xu (2011) and Qian (2017), by giving local governments

large …scal independence and evaluating them based on a common set of criteria that weigh

heavily on local economic performance, regional governors are greatly incentivized to become

11

helping hands, rather than grabbing hands, in developing local economies. This economic

tournament is widely recognized as a key mechanism contributing to China’s rapid growth

over the past 40 years.

In typical western countries, career concerns of politicians who aim to win local elections

may also generate incentives to develop local economies. Such incentives vary across regions

depending on the preferences and interests of local electorates. For example, voters in one

region may care more about economic growth, thus leading to greater incentives for the

local politicians to develop local economy, while voters in another region may care more

about the environment, leading the local politicians to give lower priority to developing the

economy. Having the central government as the common evaluator of all regional governors

in China dictates that they all share the same career incentives and thus compete directly

with each other. Maskin, Qian and Xu (2000) argue that the relatively homogenous economic

structures across di¤erent regions in China also make this economic tournament an e¤ective

institutional arrangement.

To incorporate the tournament, I adopt the following speci…cation of the productivity of

region i:

A

it

= e

f

t

+a

it

+"

it

;

where f

t

N

f;

2

f

represents a countrywide common shock with Gaussian distribution

of mean

f and variance

2

f

, a

it

N (a

i

;

2

a

) represents the governor’s ability in developing

the local economy, which has Gaussian distribution of mean a

i

and variance

2

a

; and "

it

N (0;

2

"

) is an idiosyncratic noise component, again with Gaussian distribution of mean 0

and variance

2

"

. These components are independent of each other, and neither of them is

publicly observable. Furthermore, their distributions are common knowledge to all agents.

I assume that a new governor, randomly drawn from the distribution N (a

i

;

2

a

), is as-

signed to a region in each period. The governor works in the region for only one period

and is concerned about the central government’s perception of his ability after observing his

performance and his peers’performance. Speci…cally, suppose that a governor takes over

region i at the end of period t after Y

it

is realized, and chooses E

G

it

and G

it+1

. As the gov-

ernor’s ability a¤ects the local productivity at t + 1, the local output Y

it+1

provides useful

information about his ability when he is evaluated by the central government at t + 1. That

is, his performance is determined by

ba

it+1

= E

h

a

it+1

j fY

it+1

g

i=1;:::;M

i

:

12

By substituting in Y

it+1

from (3), I obtain a linear expression for the log output:

y

it+1

ln (Y

it+1

) = ln

R

=(1)

A

1=(1)

it+1

G

it+1

=

1

1

(f

t+1

+ a

it+1

+ "

it+1

) +

1

ln

R

+ ln (G

it+1

) : (9)

Thus, the local output ln (Y

it+1

) provides a useful signal about the governor’s ability a

it+1

.

As the governor can boost the local output by taking on more infrastructure investment, his

career incentives motivate him to invest more in infrastructure, overcoming the preference

for more government consumption. This implicit incentive to invest in local infrastructure

is in the spirit of Holmstrolm (1982) and Gibbons and Murphy (1992).

To analyze this mechanism, I assume that the central government cannot observe the

stock of local infrastructure (i.e., G

it+1

) and other input in local production. Instead, it

observes only the output level Y

it+1

. This assumption is realistic for several reasons. First, the

central government has to rely on lo cal statistics bureaus to report local statistics. As local

governments have strong in‡uences on local statistics bureaus, they have ample ‡exibility

to manage or even distort local statistics. Second, the National Bureau of Statistics devotes

a great deal of e¤ort to auditing and verifying regional output, as it is a key variable for

many policy decisions of the central government. As a result, it is harder to distort output

statistics than other factor statistics.

9

Motivated by these observations, I assume for the

rest of the paper that the central government can only use regional output to evaluate the

performance of local governors. Note that I will further modify the setting to examine

how lo cal governors may overreport regional output in Section 3 even though output is not

manipulatable in other sections.

Following Holmstrolm (1982), I assume that the central government has rational expecta-

tions and anticipates the local governor’s choice. That is, even though the central government

does not observe the local governor’s choice G

it+1

, it anticipates that the local governor will

choose G

it+1

equal to the equilibrium level G

it+1

. As a result, in interpreting the observed

output, the central government would simply deduct the anticipated level ln

G

it+1

from

9

One might still argue that it is easier to observe infrastructure than GDP. As argued by Pritchett (2000),

adding up investment may not be an accurate measure of actual installed capital because of cream-skimming

and corruption. For the same reason, the observed infrastructure may not represent quality of infrastructure

and thus cannot be used as a reliable measure of regional performance.

13

the observed log output y

it+1

; by constructing the following su¢ cient statistic:

z

it+1

(1 )

y

it+1

1

ln

R

+ ln

G

it+1

= f

t+1

+ a

it+1

+ "

it+1

+ (1 )

ln (G

it+1

) ln

G

it+1

: (10)

From the central government’s perspective in interpreting the information content of this

statistic, G

it+1

= G

it+1

and thus

z

it+1

= f

t+1

+ a

it+1

+ "

it+1

: (11)

Due to the common shock in each region’s productivity, the central government will use

the outputs from all regions to jointly infer each governor’s ability. This joint evaluation

leads to a tournament in which each governor’s performance is compared with that of other

governors. By directly applying the Bayes Theorem based on the composition of z

it+1

given

in (11), I obtain the following learning rule for the central government:

^a

it+1

= E

h

a

it+1

j fz

it+1

g

i=1;:::;M

i

= a

i

+

2

a

2

a

+

2

"

+ (M 1)

2

f

(

2

a

+

2

"

)

2

a

+

2

"

+ M

2

f

(z

it+1

z

it+1

)

2

a

2

f

(

2

a

+

2

"

)

2

a

+

2

"

+ M

2

f

X

j6=i

(z

jt+1

z

jt+1

) :

From the governor’s perspective, z

it+1

depends on his own choice G

it+1

in (10). As a

result, the governor can in‡uence the central government’s perception ^a

it+1

by choosing a

higher level of G

it+1

at time t. By substituting in z

it+1

from (10), I have

^a

it+1

a

i

(12)

=

2

a

2

a

+

2

"

+ (M 1)

2

f

(

2

a

+

2

"

)

2

a

+

2

"

+ M

2

f

f

t+1

f

+ (a

it+1

a

i

) + "

it+1

+ (1 )

ln G

it+1

ln G

it+1

2

a

2

f

(

2

a

+

2

"

)

2

a

+

2

"

+ M

2

f

X

j6=i

f

t+1

f

+ (a

jt+1

a

j

) + "

jt+1

+ (1 )

ln G

jt+1

ln G

jt+1

:

This expression shows that choosing a higher G

it+1

a¤ects the central government’s percep-

tion, because the central government cannot fully separate the local governor’s ability from

its infrastructure investment. This is the basic insight of the signal-jamming mechanism

coined by Holmstrolm (1982).

Under rational expectations, the central government rationally anticipate that each local

governor j chooses G

jt+1

= G

jt+1

. Consequently, the performance evaluation of governor i

14

in (12) is not a¤ected by the infrastructure investment choice of any other governor. That is,

each governor’s career concerns are insulated from other governors’behaviors, because the

central government is able to fully …lter out any e¤ect induced by other governors. In Section

5, I will relax this rational expectations assumption to consider a more realistic setting in

which the central government can only realize the infrastructure and debt choices of local

governments with a delay.

To capture the governor’s career incentives induced by the tournament, I introduce an

additional term into the local government’s Bellman equation previously speci…ed in (6):

V (G

it

; A

it

) = max

G

it+1

E

t

ln

C

t

it

+ ln(C

t1

it

)

+ ln (W

it

G

it+1

) (13)

+

i

(^a

it+1

a

i

) + V (G

it+1

; A

it+1

)g

where

i

(^a

it+1

a

i

) is the new term with

i

> 0 as the weight assigned to the governor’s

career incentives.

10

The budget constraint remains the same as in (5). In formulating this

Bellman equation, I implicitly assume that while the governor changes in each period, other

employees of the local government will remain. As these government employees care about

their future consumption, their internal bargaining with the governor in the bureaucracy will

ensure that the governor’s infrastructure choice accounts for their future welfare, as re‡ected

by the last term in the Bellman equation.

With the additional career concern term, the relevant terms in the governor’s objective

for choosing G

it+1

on the right-hand side of the Bellman equation (13) are

max

G

it+1

E

t

ln C

t

it

+ ln (W

it

G

it+1

) +

i

ln G

it+1

+ V (G

it+1

; A

it+1

)

where

i

=

2

a

2

a

+

2

"

+ (M 1)

2

f

(

2

a

+

2

"

)

2

a

+

2

"

+ M

2

f

(1 )

i

: (14)

These terms are almost the same as those from the Bellman equation in (6), except for the

additional term

i

ln G

it+1

, which addresses the governor’s career incentives. By solving the

Bellman equation, I obtain the optimal infrastructure as summarized in the next proposition:

Proposition 3 The governor’s career incentives lead to greater infrastructure investment:

G

it+1

=

1

(1 )

+

i

+

(Y

it

+ (1

G

) G

it

) :

10

One may micro-found this term by assuming that the central government randomly pairs each governor

with another governor and promotes the one with better perception. Linearizing the expected promotion

probability leads to the linear term speci…ed in the objective.

15

Proposition 3 shows that career incentives motivate the governor to choose a greater

level of infrastructure investment. In particular, a governor with a higher

i

coe¢ cient

invests more into infrastructure. Thus, the tournament helps to overcome the underinvest-

ment problem to infrastructure, as derived in Proposition 1. This simple insight provides a

key mechanism for China’s rapid growth, as recognized by the literature mentioned in the

introduction.

Career incentives for local governors had already existed in China’s government system

even during China’s Great Famine in 1959-1961. What make the incentives so much more

e¤ective in the recent years than before? To address this important question, one needs

to recognize the development of the market sector as a result of the economic reforms that

started in late 1970s. Before the economic reforms, China had a central-planning economy

with government o¢ cials managing every aspect of the economy at all levels. In this en-

vironment, the career incentives of local governors were not enough to overcome pervasive

frictions and incentive problems that confronted every part of the Chinese economy, such as

the incentive problems of workers. The economic reforms have greatly changed the structure

of the Chinese economy by letting a substantial fraction of the economy driven by market

forces. My model also captures this market sector through the representative …rm in each

region. With the …rms driven by market forces, these forces also guide local governors’ca-

reer incentives to improve infrastructure and other market conditions that would e¤ectively

boost local productivities. This integration of local governors’career incentives with market

forces did not exist before the economic reforms.

11

Career incentives not only motivate development of local infrastructure but also short-

termist behaviors. In the subsequent sections, I analyze such short-termist behaviors, which

are important for understanding various challenges currently faced by the Chinese economy.

12

11

While my model focuses on local governors’career incentives, it is useful to note that they might also be

driven by other incentives, such as corruption. To the extent that China’s recent anti-corruption campaign

has uncovered a large number of corrupted o¢ cials, one may infer that a certain fraction of the government

o¢ cials take payments from corruption. I would argue that the presence of corruption does not necessarily

invalidate the incentive mechanism highlighted by my model and, to the contrary, may reinforce it. To the

extent that a governor may be able to extract greater side payments from local …rms when th e …rms are

more productive, the side payments give another source of incentives that motivate the governor to invest

more to infrastructure. In fact, one can eas ily expand my framework to capture such incentives by adding

another utility term to the Bellman equation for the governor’s personal gain from side payments that are

proportional to local output.

12

Based on the local governor’s optimal infrastructure investment derived in Proposition 3, it is possible

for the central government to d esign an incentive program, i.e., a suitable coe¢ cient

i

, to fully impleme nt

the …rst-best investment level in Prop osition 2. The choice of

i

would need to adjust for the governor’s

career stage, as re‡ected by the prior variance regarding his ability, and the local economic structure, as

16

3 Output Overreporting

China has a multilayered structure for reporting economic statistics. The National Bureau of

Statistics (NBS) reports national statistics, while local statistics bureaus, which are subject

to strong in‡uence from local governments, report local statistics. Chen et al. (2018) and

Hortacsu, Liang and Zhou (2017) report that the sum of provincial GDP has been routinely

higher than the national GDP by an amout in the order of …ve percent of national GDP. This

substantial gap, which is also illustrated in Section 6, suggests that local statistics bureaus

in aggregate overreport provincial GDP. Furthermore, Chen et al. (2018) provide forensic

analysis of overreporting of provincial GDP and capital investment.

In this section, I analyze overreporting of regional output induced by the career concerns

of local governors. To examine this issue, I modify the model setting by assuming that

the central government does not directly observe the regional output in the current period.

Instead, each governor reports the output of his region to the central government. This gives

each governor the ‡exibility to overreport his performance. To discipline overreporting, the

central government takes away a fraction of the reported output as tax revenue to fund

central government spending. This assumption is consistent with the split tax arrangement

between the central government and local governments in China. Thus, from the perspective

of a regional governor, overreporting the local output comes at the cost of a larger tax transfer

to the central government.

Speci…cally, I assume that a governor is free to report Y

0

it

as the output of his region,

which may be di¤erent from the actual output Y

it

. Or equivalently, the governor may choose

to overreport the log output y

0

it

by an amount '

it

:

y

0

it

= y

it

+ '

it

:

With the actual olog utput given by (9), the reported log output is

y

0

it

=

1

1

(f

t

+ a

it

+ "

it

) +

1

ln

R

+ ln (G

it

) + '

it

:

In interpreting the reported output, the central government anticipates the governor to invest

re‡ected by the noise structure of the local output and the composition of the local tax revenue and the

infrastructure stock. One would also need to account for the short-termist behaviors induced by the career

incentives. It is not the objective of this paper to analyze this optimal design. Instead, I take the ince ntive

program as given and analyze its various e¤ects on the economy.

17

G

it

in infrastructure and overreport by '

it

and thus constructs the su¢ cient statistic:

z

0

it

(1 )

y

0

it

1

ln

R

+ ln (G

it

)

'

it

= f

t

+ a

it

+ "

it

+ (1 ) [ln (G

it

) ln (G

it

) + ('

it

'

it

)] :

Again, bear in mind that from the central government’s perspective ln (G

it

) = ln (G

it

) and

'

it

= '

it

in equilibrium, while from the governor’s perspective it controls both G

it

and '

it

.

Consequently, the central government follows the same learning rule as before:

^a

it+1

a

i

= E

h

a

it+1

j

z

0

it+1

i=1;:::;M

i

a

i

=

2

a

(

2

a

+

2

"

)

(

2

a

+

2

"

)

2

a

+

2

"

+ M

2

f

f

t+1

f

+

2

a

2

a

+

2

"

+ (M 1)

2

f

(

2

a

+

2

"

)

2

a

+

2

"

+ M

2

f

(a

it+1

a

i

) + "

it+1

+ (1 )

ln G

it+1

ln G

it+1

+ '

it+1

'

it+1

2

a

2

f

(

2

a

+

2

"

)

2

a

+

2

"

+ M

2

f

X

j6=i

(a

jt+1

a

j

) + "

jt+1

+ (1 )

ln G

jt+1

ln G

jt+1

+ '

jt+1

'

jt+1

:

Like before, the central government’s perception of the governor’s ability ^a

it+1

a

i

is tied

to his output overreporting '

it+1

'

it+1

. Even though the central government rationally

anticipates the governor to overreport by '

it+1

= '

it+1

and, consequently, the overreporting

does not a¤ect the central government’s perception in the equilibrium, the governor still has

to overreport by this amount, as overreporting less will lead to a worse perception. This is

again due to the signal jamming mechanism.

I further expand the tax system by assuming that the local government needs to transfer

part of its tax revenue to the central government at a rate of

c

< based on the reported

output level Y

0

it+1

. In other words, while the local government collects a tax of Y

it+1

based

on the actual output, it has to transfer a greater fraction of the tax revenue to the central

government if it chooses to overreport the output. Then, the residual tax revenue for the

local government is

T

it+1

= Y

it+1

c

Y

0

it+1

= Y

it+1

1

c

e

'

it+1

: (15)

A higher overreporting '

it+1

thus reduces the local budget for the following perio d.

18

I now revisit the governor’s Bellman equation:

V (G

it

; T

it

) = max

G

it+1

; '

it+1

E

t

[ ln ((1

G

) G

it

+ T

it

G

it+1

) +

i

(^a

it+1

a

i

) + V (G

it+1

; T

it+1

)] ;

subject to the next period budget in (15). To simplify the setting, I let = 0; i.e., the

governor assigns zero weight to household consumption for the remaining parts of the pa-

per. I also modify the state variables to fG

it

; T

it

g, which are informationally equivalent to

fG

it

; A

it

g.

13

The relevant terms in the governor’s objective for choosing G

it+1

and '

it+1

on

the right-hand side of the Bellman equation are

max

G

it+1

; '

it+1

ln ((1

G

) G

it

+ T

it

G

it+1

) +

i

ln (G

it+1

) +

i

'

it+1

'

it+1

+ E

t

h

V

G

it+1

; Y

it+1

1

c

e

'

it+1

i

:

The term

i

'

it+1

'

it+1

; with

i

given in (14), captures the governor’s incentive to boost

his career by overreporting the output, while the last term E

t

V

G

it+1

; Y

it+1

1

c

e

'

it+1

contains the cost of leaving a smaller …scal budget for the next period.

By solving this Bellman equation, the next proposition con…rms that the governor’s career

concern indeed leads to overreporting of the local output, and such overreporting increases

with his career incentive

i

and decreases with the central government tax rate

c

.

Proposition 4 The governor’s output overreporting is given by the following equation:

'

it+1

= ln

(1 )

i

c

(

i

+ )

ln

(

R

=(1)

E

t

"

A

1=(1)

it+1

1

G

+

1

c

e

'

it+1

R

=(1)

A

1=(1)

it+1

#)

;

which has a unique root between 0 and ln (=

c

) under the conditions (25) and (26) listed in

the Appendix. This root is increasing with

i

and decreasing with

c

.

This mechanism for regional governors to overreport output is similar in spirit to that

for earnings manipulation by publicly listed …rms, e.g., Stein (1989). As …rm managers

have incentives to boost their stock prices, the signal jamming mechanism causes them to

overreport …rm earnings, despite that investors rationally anticipate such overreporting and

deduct it from stock valuation. By con…rming this mechanism, Proposition 4 suggests that

13

With rational expectations, the central government fully anticipates the local governor’s overreporting.

As a result, even though the central government does not directly observe G

it

and T

it

, it can nevertheless

infer their values in each period and thus anticipate the governor’s optimal strategy. This feature is common

to the signal jamming models and greatly simpli…es the equilibrium analysis, relative to an alternative setting

in which the central government cannot fully infer the governor’s overreporting.

19

the lack of reliable economic statistics in China may not be random noise and instead could

be a systematic problem associated with China’s government bureaucracy. As far as I know,

the literature has not recognized this important aspect. Furthermore, Proposition 4 also

provides useful comparative statics that the overreporting of local output is increasing with

the local governor’s career incentives and decreasing with the lo cal government’s …scal cost

of overreporting.

In recent years, several Chinese provinces have publicly acknowledged their GDP over-

reporting in the past. For example, in early 2017, the provincial government of Jiaoning

revealed in its annual report submitted to its People’s Congress that it had systematically

over-reported Liaoning’s economic statistics in 2011-2014. In January 2018, the provincial

governments of both Inner Mongolia and Tianjing also confessed that they had also in‡ated

their economic statistics in the previous years. Such confessions were partly driven by large

shortfalls in their …scal budgets, as the confession relieved these provincial governments o¤

the additional …scal pressure induced by the overreporting, as consistent with the model.

14

The output overreporting by local governors may have another important economic con-

sequence by distorting the central government’s information set. In my current setting,

the central government fully anticipates the overreporting of the local governors due to the

assumption of rational expectations. Under more realistic settings, overreporting by local

governors may distort the expectations of the central government regarding the regional

economies, as well as the overall national economy. Such expectational distortions may

in turn reduce the e¢ ciency of the central government’s economic policies, which is a key

concern about China’s unreliable economic statistics.

15

14

For simplicity, I would leave it to future work to explicitly incorporate such public confess ion into the

model as a way to unwind previous overreporting. Interestingly, this kind of confession typically happens after

the previous governors lose their prominence as a result of corruption investigations or other misbehaviors.

Otherwise, such confession runs the political risk of o¤ending the previous governors, who might have and

may become national leaders.

15

This concern has been illustrated by the Great Famine of China in 1959–1961. Fan, Xiong and Zhou

(2016) …nd that during this period, overreporting of regional grain output by local governments led to greater

procurement of grain to the central government and more severe famine in the region. In particular, they

argue that the widely-spread overreporting of grain output, ind uce d by the Great Leap Forward, made the

central government unaware of the national famine, which explains the lack of any relief e¤ort by the central

government even at the peak of the famine in 1960. In contrast, China shipped a large quantity of grain

either as export or food aid to other countries at the time.

20

4 Excessive Leverage

So far I have restricted regional governments from using any debt to leverage their …scal

budgets. This assumption is realistic for China in the period before 2008, as the central

government had strict rules against subnational governments’raising debt without its explicit

approval. However, the situation changed substantially after 2008, when the global …nancial

crisis prompted China to implement a massive economic stimulus of four trillion RMB. As

the stimulus was mostly …nanced by …scal budgets of local governments (rather than that

of the central government), and the stimulus required much more …nancing than what local

governments could a¤ord, the central government allowed local governments to establish the

“local government …nancing vehicle”(LGFV), which used explicit or implicit guarantees from

local governments to obtain bank loans to fund the stimulus projects, e.g., Bai, Hsieh and

Song (2016). After the stimulus program ended in 2010, the central government instructed

banks to discontinue lending to local governments. Facing pressure to roll over their maturing

loans, local governments moved their debt …nancing into shadow banking, as analyzed in

detail by Chen, He and Liu (2017), leading to even higher leverage. Zhang and Barnett

(2014) provide an estimate that debt …nancing (in the forms of both bank loans and shadow

banking debt) contributed to about two-thirds of infrastructure investment in China in 2008–

2012.

Debt gives a governor a greater capacity to invest in local infrastructure and thus may

exacerbate his short-termist behavior induced by career concerns. To address this issue, I

further extend the model setting. Speci…cally, I anchor on the setting from Section 2 (without

output overreporting and tax transfer to the central government), and allow each regional

government to use debt to …nance its infrastructure investment and spending. Speci…cally,

I assume that it can issue debt at a constant interest rate R: Then, its budget in period t

is its tax revenue from the previous period Y

it

plus the stock of infrastructure (1

G

) G

it

minus its debt due RD

it1

:

W

it

= Y

it

+ (1

G

) G

it

RD

it1

:

The governor can take new debt D

t

, in addition to W

it

; to fund the next-period infrastructure

G

it+1

and government consumption E

G

it

:

G

it+1

+ E

G

it

= W

it

+ D

it

: (16)

21

I modify the Bellman equation in (13) by letting = 0 for simplicity and by giving the

governor the additional debt choice in each period:

V (W

it

) = max

G

it+1

; D

it

ln (W

it

+ D

it

G

it+1

) +

i

ln G

it+1

ln G

it+1

(17)

+ E

t

[V ( Y

it+1

+ (1

G

) G

it+1

RD

it

)] ;

subject to the new budget constraint in (16).

16

It shall be clear that W

it

is su¢ cient to

capture the state of the regional economy at time t; despite the use of debt.

To facilitate the analysis, I scale the local government’s infrastructure in each period by

its budget:

g

it+1

=

G

it+1

W

it

;

and debt level by its infrastructure level:

d

it

=

D

it

G

it+1

:

d

it

can be directly interpreted as the fraction of infrastructure …nanced by debt. As I formally

derive in the Appendix, debt allows the governor to take on a higher level of infrastructure

relative to its current-perio d budget:

g

it+1

=

+

i

+

i

1

(1 d

it

)

:

A certain level of debt is socially bene…cial as it allows the regional government to expand

its budget to fully take advantage of high productivity in the current period. However, the

governor’s career concerns may induce excessive use of debt to …nance overinvestment at

the expense of a higher debt payment and thus a smaller budget in the next period. To

systematically examine this issue, I also examine the debt choice of a social planner who

aims to maximize the welfare of both the government and the households. Following the

setting in Section 1.3, the planner’s budget at time t is

W

planner

it

= Y

it

+ (1

G

) G

it

RD

it1

;

which also includes repayment of the local government debt from the previous period. The

planner can also use new debt to boost its current period budget:

C

t

it

+ C

t1

it

+ E

G

it

+ G

it+1

= W

planner

it

+ D

it

16

The logarithmic utility function ensures that the local governor will avoid any possibility of future

default. In this sense, my setting implicitly assumes that the local government has hard budget constraints,

i.e., it cannot run a Ponzi scheme by continuing to borrow more and more. Despite the absence of soft

budget constraints, my setting is nevertheless able to capture important short-termist behaviors of local

governments, such as excessive leverage and overinvestment.

22

to …nance infrastructure investment G

it+1

, together with the consumption of the two gener-

ations of households C

t

it

and C

t1

it

and the government consumption E

G

it

: Then, the planner’s

Bellman equation is given by

V

W

planner

it

= max

G

it+1

;C

t

it

;C

t1

it

;E

G

it

;D

it

E

t

h

ln

C

t

it

+ ln(C

t1

it

) + ln E

G

it

+ V

W

planner

it+1

i

:

(18)

I directly solve the Bellman equation of both the governor in (17) and the planner in

(18). Interestingly, their debt choices are determined by a maximization problem with the

same structure except di¤erent coe¢ cients, as summarized in the following proposition:

Proposition 5 Both the governor and the social planner would choose a debt level of d

it

=

D

it

=G

it+1

in the interval [0; (1

G

)=R] ; based on the following maximization problem:

max

d

it

ln

1

1 d

it

+ E

t

ln

R

=(1)

A

1=(1)

it+1

+ (1

G

) Rd

it

; (19)

where the coe¢ cient is 1 for the planner and

1

i

+

i

+ 1 for the governor. If

E

t

"

R

R

=(1)

A

1=(1)

it+1

+ (1

G

)

#

< < E

t

"

R +

G

1

R

=(1)

A

1=(1)

it+1

#

;

there is an interior debt choice. The governor’s debt choice is always higher than the plan-

ner’s, and the governor’s debt choice is increasing with his career incentive parameter

i

.

This proposition shows that career concerns indeed lead the governor to take on excessive

debt, i.e., a debt level higher than the level chosen by the so cial planner. In cho osing the

debt level, both the governor and the planner face the same intertemporal tradeo¤— a higher

debt level boosts the current period’s output, as re‡ected by the …rst term in (19), at the

expense of a higher debt payment in the following p eriod, as re‡ected by the second term in

(19). The career concern causes the government to assign a greater weight to the …rst term,

leading to a higher debt choice.

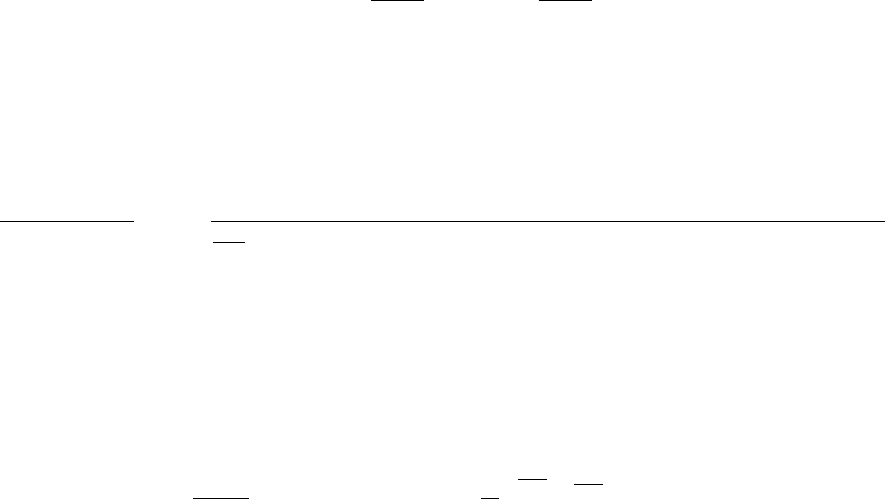

To further illustrate the governor’s debt choice, Figure 1 depicts the debt choices of the

governor and the planner under a set of baseline parameter values:

= 0:2; = 1=3; R = 1:1;

G

= 0:05; = 0:9; = 1;

f = a = 0:05;

f

= 0:4;

a

= 0:4;

"

= 0:2;

i

= 1:

23

0 2 4 6 8 10

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1.4 1.6 1.8 2

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

Figure 1: Leverage with Career Incentives and Expected Growth

The left panel depicts d

it

by varying

i

between 0 and 10. The governor’s debt choice

coincides with the planner’s choice when

i

= 0. As the governor’s career incentives rise with

i

, his debt choice also rises with

i

. The right panel depicts the debt choices of the governor

and the planner by varying the expected productivity growth E (A

i

). As expected, both debt

choices are increasing with E (A

i

), with the governor’s debt choice always higher than the

planner’s. Taken together, this section describes a mechanism for the local governor’s career

concerns to lead to overinvestment in infrastructure by using excessive leverage.

5 Leverage Spillover

Policy innovations and …nancial innovations can complicate the agency problem between the

central and local governments. In this section, I analyze a novel channel through which

innovations can cause short-termist leverage choices by one governor to spill over to other

governors.

The discussion of local governors’career concerns so far builds on the premise that the

central government fully anticipates each regional governor’s short-termist behaviors (such

as overreporting and excessive leverage) with rational expectations and, consequently, is

24

able to perfectly …lter the e¤ect of any short-termist behavior of one governor on the rel-

ative performance evaluation of other governors. This means that short-termist b ehaviors

do not spread across governors. Innovations may prevent the central government from fully

anticipating the short-termist behaviors of local governments. First, as part of the key grad-

ualistic approach adopted by China to reform its economy over the past 40 years, the central

government encouraged local o¢ cials to experiment with policy reforms and innovations at

the regional level and also to follow and imitate promising policy initiatives of other regions.

When a new policy initiative emerges, the central government often takes a passive mode of

simply observing its e¤ects before eventually determining whether to endorse or terminate

it. Xu (2011) gives an extensive review of this reform approach and argues that it has played

an important role in China’s institutional development. This reform approach implies that

the central government is, by design, slow to catch up with the policy innovations of local

governments.

Second, …nancial innovations further complicate the central government’s learning process

of new strategies and new games created by local governments. This is because …nancial

innovations provide new instruments and new arrangements for local governments to strate-

gically hide or reveal part of their …nancial transactions and …scal conditions to the central

government. For example, various shadow banking products, such as wealth management

products, allow banks to move regular bank loans made to local government …nancing vehi-

cles o¤ their own balance sheets. By doing so, banks are able to make at least some of these

loans o¤ the radar of the central government. While it is easy for the central government to

anticipate the incentives of local governments to pursue short-termist behaviors, the lack of

transparent statistics makes it di¢ cult for the central government to …gure out the speci…c

form and magnitude of such behaviors, when they are hidden behind complicated …nancial

arrangements.

If the central government does not fully anticipate the debt and investment levels taken by

each lo cal government, the tournament between the regional governors may take a di¤erent

form because short-termist behaviors by one governor can also motivate other governors to

pursue short-termist strategies, which in turn may feed back to the initial governor, leading

to a rat race among the governors. To formally address this issue, I suppose that the central

government faces a delay in updating its anticipation of each local governor’s investment:

25

G

it

= G

it1

, which is similar in nature to adaptive expectations.

17

Following the central

government’s learning of governor i in (12),

^a

it

a

i

=

f

t

f

+ (a

it

a

i

) + "

it

+ (1 ) (ln G

it

ln G

it1

)

0

X

j6=i

f

t

f

+ (a

jt

a

j

) + "

jt

+ (1 ) (ln G

jt

ln G

jt1

)

;

where

=

2

a

2

a

+

2

"

+ (M 1)

2

f

(

2

a

+

2

"

)

2

a

+

2

"

+ M

2

f

and

0

=

2

a

2

f

(

2

a

+

2

"

)

2

a

+

2

"

+ M

2

f

:

An immediate consequence of the central government’s adaptive expectations is that each

local governor’s career concerns are no longer immune from the investment and leverage

choices of other governors, as re‡ected by the summation term involving G

jt

in this formula.

In practice, the central government often directly compares the performance of a governor

with another governor in a region with similar economic conditions. Building on the linear

career incentive speci…ed in (17), I also add another quadratic term to the governor’s career

incentive:

V (W

it

) = max

G

it+1

; D

it

E

t

[ ln (W

it

+ D

it

G

it+1

) +

i

(^a

it+1

^a

i

0

t+1

) (20)

i

(^a

it+1

^a

i

0

t+1

)

2

+ V (W

it+1

)

;

with i

0

as the other governor paired with i and the budget constraint in (16). This quadratic

term gives an increasing incentive for governor i to catch up with the other governor i

0

.

As there are a large number of other governors, I suppose that i

0

is chosen to have the

same economic conditions: G

i

0

t

= G

it

and W

i

0

t

= W

it

. This pairing allows me to maintain

simplicity of the derivation without any loss of generality. I also make the setting symmetric

so that a

i

= a

j

= a and = = . Then, it follows that

^a

it+1

^a

i

0

t+1

= ( +

0

) [a

it+1

a

i

0

t+1

+ "

it+1

"

i

0

t+1

+ (1 ) (ln G

it+1

ln G

i

0

t+1

)] :

Consequently,

E

t

[

i