A report of the State of Vermont Office of

Racial Equity detailing community-driven

findings and recommendations for

expanding language access across all

branches of State government

E X E C U T I V E D I R E C T O R

Xusana R. Davis, Esq.

P R I N C I P A L D R A F T E R

Jay Greene, MPH

2023

LANGUAGE

ACCESS REPORT

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Office of Racial Equity thanks all the community members and

State colleagues who participated in the c o n v e r s a t i o n sessions and

provided feedback on the language access policy recommendations.

The Office is further grateful for the technical expertise, policy

guidance, drafting assistance, and additional consultation of State

staff and other concerned parties across all three branches of State

government and in all regions o f the state, including but not l imited t o :

Shalini Suryanarayana, Ian Louras, Geoffrey Pippenger, Meagan

Smeaton, Rebecca Turner, Erik Filkorn, Bor Yang, Laura Siegel, Megan

Tierney-Ward, Cheryle Wilcox, Tracy Dolan, Kristen Rengo, N i k k i

Fuller, Amila Merdzanovic, Sonali Samarasinghe, K i m Frampton, Thato

Ratsebe, Linda Li, Alison Segar, K i r s t e n M u r p h y , Seema Kumar, Scott

Griffith, Mike F e r r ant, Damien Leonard, a n d all the State staff w h o

assisted with data collection to develop the vital document cost

estimate.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 1

Summary of Findings and Recommendations ............................................................. 3

Note on Terminology: “Limited English Proficiency” or “LEP” .................................... 15

Introduction ................................................................................................................... 16

Language Access Plan Components and federal Standards ........................................ 18

Basic Components of a Language Access Plan ........................................................ 18

Federal Requirements for the Provision of Language Access Services .................... 18

Findings and Recommendations ................................................................................... 26

How to read the findings and recommendations .................................................... 26

1. Values, Framework, and Culture ........................................................................... 26

2. Data, Evaluation, and Reporting: ........................................................................... 27

3. Operations and Staff Protocols .............................................................................. 29

4. Technology and Resources ................................................................................... 32

5. Professional Development and Qualifications ....................................................... 36

6. Recommendations for ADA Compliance for People Who Use Signed Languages

and/or People with Disabilities ................................................................................... 39

Additional Policy Recommendation: Multilingual Liaison Needs Assessment ........... 42

References: ................................................................................................................... 43

Appendix A: Glossary of Abbreviations and Terminology .......................................... 47

Appendix B: Additional Resources............................................................................. 51

Language Access Planning Resources .................................................................. 51

Resources for Facilitating Language Access & ADA accessibility compliance for

People who are Deaf, Hard-of-Hearing, DeafBlind, and DeafPlus ......................... 52

Website Accessibility Resources ............................................................................ 54

Equitable Outreach and Engagement Resources .................................................. 54

Appendix C: Population Estimates of People who Speak or Sign Languages Other

than English in Vermont ............................................................................................. 56

Vermont Agency of Human Services LEP Committee ........................................... 57

Appendix D: Recommended Model Minimum Language Access Plans .................... 59

Appendix E: Department of Labor Language Access Operations Manual ................. 69

Appendix F: April 2022 Language Access Convening Summary ............................... 72

Appendix G: Executive Branch Vital Document Translation Cost Estimate ............... 86

Appendix H: Infographic Summary of Language Access Report…………………………96

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 OF 96

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Context and purpose

This report is a comprehensive

summary of the language access policy

and procedural recommendations

generated through Office of Racial

Equity (ORE) community outreach

efforts along with guidelines for creating

language access plans and policies in

the state of Vermont.

Vermont’s demographic profile is

growing in richness and complexity. As

is true in the rest of the U.S., Vermont’s

most racially and ethnically diverse age

cohorts are the Millennial and

Generation Z cohorts. As the State

seeks to grow and diversify its

population by supporting youth and

young adults, it must couple these

efforts with initiatives that embrace,

celebrate, and support multicultural and

multilingual people who are more likely

to comprise the state’s future residents

and visitors.

One way to provide this support

is through the provision of

comprehensive language access

services that allow residents and visitors

to expect consistent, predictable access

to government services no matter the

region or agency in which they find

themselves.

Process and Methodology

In early 2020, the Executive

Director conducted a baseline survey of

State agencies and departments across

all three branches to determine the

nature and extent of language access

services. With the intervening global

pandemic, the focus of this effort shifted

to emergency communications and

ensuring that time-sensitive notices

related to public health and operational

matters were prioritized for multilingual

communities.

The introduction of S.147 in 2022

demonstrated that the State was

prepared to revisit the prospect of

comprehensive language access

planning, and the Office of Racial Equity

proceeded with a community

engagement phase that collected

feedback from concerned parties around

the state.

The Office also produced

extensive research and budget

estimates that draw from promising

practices across the country to develop

findings and recommendations that

would be successful in the Vermont-

specific context.

How to read this report

You only have a few minutes, see

Appendix H for a one-page infographic

summary of the report.

You have an hour, read through this

Executive Summary with the full list of

findings and recommendations, or read

the Plain-language summary available

here: Plain-language summary.

You have over an hour, read the full

report, which contains color-coded notes

along the way. Those notes are

described below:

NOTE: Adds information or context.

EXAMPLE: Provides a model or template.

LEARN MORE: Highlights additional

source for further exploration.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 OF 96

Recommendations

The summarized list of findings

and recommendations appears on the

following pages. For additional

explanation and context, each finding

and recommendation is discussed in the

section titled Findings and

Recommendations.

A path forward

The Office looks forward to

working with impacted communities and

leaders across State government to

implement the recommendations in this

report, beginning with an inclusive and

thoughtful budgeting process that

promoted communicative autonomy and

language justice for Vermont’s

increasingly multilingual residents and

visitors.

ORE estimates a one-time cost of

$3.5 million for vital document

translation across the Executive branch

(that is, not including vital documents for

the Legislative or Judiciary branches),

not including ASL translation. Separate

from this one-time cost to bring the

Executive agencies into basic federal

compliance, ORE estimates an upper

limit of $790,000 per year to maintain

up-to-date translated documents and to

provide language access services

across the agencies.

These estimates do not include

the Judicial branch because of the

substantial work the Judiciary has

completed regarding incorporating

language access into its operations and

services. These estimates also do not

include the Legislature because of the

many variables that would need to be

identified and resolved in order to know

the full scope of the Legislature’s

language access needs.

Already know what you’re

looking for? Click below to skip

to the right section:

Summary of Findings and

Recommendations

Overview

Full Findings & Recommendations

Model Minimum Language Access

Plans

Vital Document Translation Cost

Estimates

References Cited

Glossary of Terms & Acronyms

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 OF 96

Summary of Findings and Recommendations

(NOTE: FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ARE GROUPED BY CATEGORY, NOT BY RELATIVE IMPORTANCE)

NO.

TOPIC

FINDING

RECOMMENDATION

NOTES

1.A

Values,

Framework, &

Culture

State of Vermont has

no unified values

statement regarding

language access.

Draft & publicize a Values

Statement that State government

is committed to language access.

Requires action by Vermont General

Assembly and/or Governor’s

Administration. See Appendix D:

ORE Model Minimum Recommended

Language Access Plans for

additional details.

Require State agencies to adopt

a model minimum language

access plan.

1.B

Values,

Framework, &

Culture

Language service

providers’ work is often

undervalued and

uncompensated.

Increase compensation for State-

contracted language service

providers to allow them to pay

their employees a living wage.

Requires contract renegotiation

between the State and language

access service providers and

associated funding increases.

2.A

Data,

Evaluation, &

Reporting

State agencies will

have unique needs for

implementing language

access services. The

details of each agency’s

language access plan

may vary by agency or

time period.

Require State agencies to file a

language access plan with ORE

to ensure that minimum

recommended best practices are

met statewide.

Requires action by Vermont General

Assembly and/or Governor’s

Administration.

Require agencies to review and

revise their plans on a defined

schedule. ORE suggests

reviewing once per year for the

first 5 years following

implementation, then every 5

years thereafter.

2.B

Data,

Evaluation, &

Reporting

Tracking expenditures

and evaluating

programmatic needs

related to language

access services is

extremely difficult

Train State employees on how to

use specific accounting codes to

bill for different types of language

services to aid in the tracking and

reporting of language access

service-related expenditures.

Funding vital document translation

requires action by Vermont General

Assembly and/or Governor’s

Administration.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 OF 96

based on current billing

practices, which

frequently do not

specify the language in

which services were

provided or the type of

language assistance

that was provided.

Finalize the cost estimate for

translation of vital documents on

a programmatic level.

Track any costs relating to

updating existing vital documents

that have already been

translated, and costs related to

translating existing translated

vital documents into additional

languages.

2.C

Data,

Evaluation, &

Reporting

Limited data are

available to help

quantify the number of

people in Vermont who

speak or sign

languages other than

English.

Require all State entities to

maintain records of the type of

language service provided and

the language in which the service

was provided to facilitate

language access services

evaluation.

Ensure that personally identifiable

information of people with language

access needs are not stored in the

same data sets as the tracking of

language access services expenses

to protect the privacy of people with

language access needs.

3.A

Operations &

Staff

Protocols

Many State agencies,

departments, and

divisions do not

currently possess

adequate financial

resources or dedicated

staffing to implement

the language access

plans required by

federal regulations. The

utilization of language

access services is likely

to increase as State

agencies communicate

the availability of

language access

Evaluate whether additional staff

positions are necessary to

support equitable language

access implementation.

Requires action by Vermont General

Assembly and/or Governor’s

Administration.

Designate at least 1 primary

State employee and 1 secondary

to be a point of contact for

language access within each

department.

Permit agencies to request

additional staff positions for

language access implementation.

Permit agencies to exceed level

funding budget requests if

requests are related to vital

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 OF 96

services more

effectively.

document translation or other

language access services.

3.B

Operations &

Staff

Protocols

State agencies do not

uniformly distribute

information on how to

access free language

services when mailing

out notices that require

a response or contain

essential information.

Include information on how to

access free language services in

any mailed or electronic

communication.

See “Vital Documents” for additional

information on the ORE

recommended languages for

translated notices of the availability of

language services.

3.C

Operations &

Staff

Protocols

Some people who

speak or sign

languages other than

English are not aware

that the State must pay

for language services

on their behalf.

Ensure that notices of language

access services communicate

that such services are free to

access.

3.D

Operations &

Staff

Protocols

Vital documents are not

routinely translated into

languages other than

English across State

entities.

Identify all vital documents

across all 3 branches of State

government.

Periodic reviews of language access

policies should include a review of

vital documents to ensure they are up

to date.

Track expenditures related to

keeping vital documents up to

date as part of overall language

access expenditure tracking.

3.E

Operations &

Staff

Protocols

Some vital documents

may be too long or

technical for the

average reader to

understand, even after

translation.

Create a plain-language

summary of long or technical vital

documents before translation to

ensure translated information is

relevant and accessible.

See Appendix B: Additional

Resources for more information on

plain language.

3.F

State employees can

better utilize existing

Audit all State records

management software systems

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 OF 96

Operations &

Staff

Protocols

software systems to

alert State employees

of the need to reserve

interpretation services

when working with

people who speak or

sign languages other

than English.

for their ability to identify people

who may require language

access services.

Configure records management

software systems to alert State

employees to arrange for

interpretation services or other

language assistance services

prior to meetings with the clients

who need them.

3.G

Operations &

Staff

Protocols

Most State employees

only speak English,

which can be a barrier

to language access in

State offices where

services are regularly

provided in-person.

At all public-facing offices, utilize

“I Speak” cards with a with a

standard written list of yes/no

questions in VT’s most

commonly spoken languages,

plus an electronic device with a

video ASL version to facilitate

providing language access

services.

See Appendix B: Additional

Resources for more information on “I

Speak” cards and an example of a

CAPS online training for interacting

with people with hearing loss.

Train State employees to use “I

Speak” cards and how to access

existing state-contracted

language service providers.

3.H

Operations &

Staff

Protocols

Multilingual State

employees interpreting

for clients could create

conflicts of interest or

other ethical/privacy

concerns for the clients

and/or State

employees.

Prioritize accessing the services

of dedicated, trained interpreters

from State-contracted service

providers rather than relying on

multilingual State employees to

interpret on behalf of clients.

3.I

There is no standard

operating procedure to

Implement standards regarding

quality of service, certification,

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 OF 96

Operations &

Staff

Protocols

assess the sufficiency

of the language skills of

multilingual State

employees before

having them provide

interpretation services.

There is no standard

protocol for fairly

compensating

multilingual employees

who provide language

assistance services as

part of their jobs.

and conflict of interest for

multilingual State employees

before asking them to provide

interpretation services that entail

more than a casual welcoming

conversation.

Requires action by Vermont General

Assembly and/or Governor’s

Administration.

Any changes to multilingual State

employees’ compensation may

require negotiation between the

Department of Human Resources

and other entities.

Consider creating a new time

reporting code in the State

employee timekeeping portal to

pay certified multilingual

employees for providing

language services.

3.J

Operations &

Staff

Protocols

Most State staff do not

get enough practice

with language access

scenarios to confidently

utilize the language

access services

available through State

contracts.

Identify State employees to

oversee testing and training for

language access.

Regularly test language access

services with “secret shopper”

programs.

Provide additional support and

training as needed if tests reveal

deficiencies in State employees’

language service skills.

4.A

Technology &

Resources

State websites do not

provide links to

translated documents

or notices of the

availability of language

assistance in obvious,

Include notices of the availability

of language assistance on the

home page of every State

website.

See “Vital Documents” and Appendix

C for additional discussion of which

languages to translate notices of the

availability of language services into.

Make a video version of the

notice of the availability of

language assistance in ASL.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8 OF 96

easy to access places

on the home page.

Display the website links to

notices of language services in

the language they are translated

into, not in English.

4.B

Technology &

Resources

In most cases, State

websites are only

available in English,

and are only translated

into other languages via

Google Translate.

Google Translate is an

insufficient resource for

translation due to errors

that can create safety

concerns.

Create a mechanism by which

people can request translated

versions of websites. Make sure

any link to information about

translation requests is displayed

in languages other than English.

If Google Translate is used,

ensure that there are obvious

disclaimers in multiple languages

about the limitations of Google

Translate. Ensure that any

Google Translate disclaimers are

located in an obvious place at the

top of a webpage and that the

links to the disclaimers are

displayed in languages they are

translated into.

Include information about how to

request interpretation services

within the Google Translate

disclaimers.

All notices of the availability of

language access services must

say that language access

services will be provided to the

public at no cost to the person

requesting the services.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 9 OF 96

4.C

Technology &

Resources

Complaint pages on

State websites are all in

English, which creates

a communication

barrier for people who

speak or sign

languages other than

English to make their

complaints known to

the State.

Create videos in the ORE

recommended languages for

notices of language services,

including ASL, that explain the

complaint process.

The Agency of Digital Services (ADS)

should coordinate the rollout of a

template complaint page that can be

added to all State websites in all the

recommended languages discussed

in this report.

Translate complaint pages into

more languages than English.

Use State-contracted interpreters

to facilitate communication

between the complainant and

State employees.

4.D

Technology &

Resources

State websites are

seldom formatted to be

easily accessible via

mobile phone or tablet.

Audit the mobile and tablet

versions of State websites for

usability in English and for

usability when translated into

other languages.

See Appendix B for more information

on website accessibility audits.

Complete a disability accessibility

and mobile/tablet usability audit

each time there are significant

updates made to State websites.

4.E

Technology &

Resources

Most State-authored

public service

announcements and

emergency

communications are

created only in English

without translated audio

or captions.

Create public service and

emergency communications with

manually translated captions (not

auto generated) and video or

audio readings in Vermont’s most

commonly spoken languages.

Any additional federal regulations

relating to telecommunications that

must be followed when considering

how to implement the

recommendation related to open

captions.

Produce emergency

communications and public

service announcements in video

format to improve access for

people who are not literate in

their native languages.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 10 OF 96

Use open captions in English in

addition to closed captions to

assist Hard of Hearing and late-

deafened people who are not

familiar with technology in

accessing captions.

4.F

Technology &

Resources

The three branches of

State government each

use a different

videoconferencing

platform, which creates

inconsistency in how

the public can engage

with captioning and

interpreters.

Choose one video conferencing

platform to simplify language

access protocols across all State

government branches.

OR

Publish detailed guides on how

to use in each of the video

conferencing software platforms

(Microsoft Teams,

Zoom/ZoomGov, and WebEx).

Requires action by Vermont General

Assembly and/or Governor’s

Administration.

Distribute a link to the relevant

video conferencing software

guide when setting up video

conferencing meetings with

members of the public or when

posting notices of public

meetings that will have a remote

access option.

Translate video conferencing

software guides into the most

commonly spoken languages in

Vermont and include notices of

the availability of free language

access services.

4.G

Technology &

Resources

Community feedback

and national research

indicates that

Consider purchasing a paid

ZoomGov account if a State

entity frequently interacts with

As of January 2023, Microsoft Teams

is in the process of adding specific

accessibility features for video

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 11 OF 96

Zoom/ZoomGov

currently has the best

suite of features for

video remote signed

language interpretation

and other needs of

people with hearing

loss

people who require video remote

interpreting services.

remote interpreters that will be

available to all State employees.

Refer to discussion of best

practices for using

videoconferencing software with

video remote interpreters in

Appendix B when utilizing the

services of video remote

interpreters.

5.A

Professional

Development

&

Qualifications

National vendors offer

interpreters who do not

always understand local

place names,

geographic features, or

other concepts relevant

to people in Vermont.

Implement job training programs

or other initiatives that aim to

recruit additional interpreters and

translators to Vermont to

increase the supply of locally

knowledgeable language service

providers.

Requires action by Vermont General

Assembly and/or Governor’s

Administration.

Recruiting more language service

providers to Vermont has the added

benefit of growing and retaining the

State’s multicultural population.

Increase compensation to State-

contracted language assistance

service providers.

5.B

Professional

Development

&

Qualifications

There is not enough

consistency in the

quality of language

assistance services

provided under State

contracts.

Establish statewide translation

and interpretation licensure

and/or certification programs.

Consult with all applicable

concerned parties when

designing statewide standards

for language assistance service

providers.

Requires action by Vermont General

Assembly and/or Governor’s

Administration.

Develop a complaint procedure

for when State employees

receive complaints regarding the

quality of service provided by

State-contracted language

service providers.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 12 OF 96

5.C

Professional

Development

&

Qualifications

Licensure and/or

certification programs

may create barriers to

entering the language

services profession,

which may include

financial barriers such

as tuition fees or

licensure fees.

Any licensure/certification

program should be designed to

remove barriers to the

profession, such as subsidizing

the cost of licensure/certification

so that such requirements do not

decrease the availability of

language services professionals.

People who speak languages that

are less commonly spoken in

Vermont (also called languages of

lesser diffusion) may be especially

vulnerable to economic or

educational barriers if they are

recently relocated refugees or

immigrants.

5.D

Professional

Development

&

Qualifications

Many testing and

professional exam

materials are not

translated into

languages other than

English.

Provide educational materials

and tests for jobs that require

licensing/credentialing but do not

require English language

proficiency in more languages

than just English.

Translating testing and professional

exam materials into languages other

than English for jobs where English

proficiency is not required is part of

ensuring federal compliance with

language access regulations.

6.A

ADA

Compliance

Assistive technologies

may not be able to

facilitate access to

websites if websites are

not designed to work

with assistive

technology such as

screen readers.

Audit all State websites for

accessibility to people with

disabilities who rely on assistive

technology.

6.B

ADA

Compliance

All State websites are

designed based on an

accessible template,

but the addition of

content to the template

may change whether

the website remains

truly accessible.

Perform an accessibility audit

any time a State website’s

contents are added to or

updated.

6.C

ADA

Compliance

Few State websites

have notices about the

Create a dedicated link on the

home page of every State entity

See “Vital Documents” and Appendix

C for additional discussion of which

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 13 OF 96

availability of disability

accessibility

accommodations for

needs unrelated to

language access in

obvious, easy to find

places on the website.

discussing the available

accessibility resources that

members of the public can

access if they need

accommodations.

languages to translate notices of

disability accessibility

accommodations into.

Invest the resources necessary

to ensure ADA compliance.

Translate the links to disability

accessibility resources into

languages other than English.

6.D

ADA

Compliance

Important public service

announcements and

emergency

communications are

seldom translated into

ASL or other signed

languages.

Translate all public service

announcements and emergency

communications into ASL.

6.E

ADA

Compliance

Relying on automated

captioning to provide

captions is insufficient

to ensure people with

hearing loss can

understand public

service announcements

and emergency

communications.

Use live or manually translated

captioning services for all

important public service

announcements and emergency

communications.

If relying on automated

captioning, review automated

captioning for errors and correct

them before distributing any

video materials publicly.

Add open captioning in English

addition to videos in addition to

closed captioning whenever

possible.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 14 OF 96

6.F

ADA

Compliance

Currently there are no

hearing loop systems

installed in owned or

leased State buildings,

which means State

employees and

members of the public

with hearing loss who

use hearing aids and/or

cochlear implants are

not currently able to

fully participate in

meetings and events

held in State buildings.

Create a plan for addressing

communication access within

State buildings for people with

hearing loss, such as installing

hearing loops in at least one

meeting room in each State-

owned building.

7

Additional

Policy

Recommenda

tion-

Multilingual

Liaison Needs

Assessment

English language

learner (ELL) students

have barriers to

learning because of

lack of language access

resources in Vermont

schools. The number of

ELL students is likely to

increase in the near

future due to Vermont’s

population

demographics and

international trends.

Conduct a statewide assessment

of ELL students’ needs with

regards to multilingual liaisons

who can assist ELL students and

their families in overcoming

language barriers.

Included in ORE policy proposals in

Legislative Session 2023. For further

discussion, see "Additional Policy

Recommendation: Multilingual

Liaison Needs Assessment” and

pages 11-12 of the First Report of the

Vermont Racial Equity Task Force

(Davis et. al, 2020).

1

Provide sufficient resources to

schools to remedy the current

lack of multilingual liaisons

following the statewide needs

assessment.

1

Full URL: https://racialequity.vermont.gov/document/racial-equity-task-force-report-1

ON TERMINOLOGY 15 OF 96

Note on Terminology: “Limited English Proficiency” or “LEP”

LEP or “limited English proficiency” is a term commonly used by federal

government sources and some State of Vermont sources to describe people who do not

fluently speak or read English. The Office of Racial Equity does not recommend using

“LEP” due to the biased nature of the term “limited English proficiency.” Characterizing

people solely by their lack of English proficiency is disrespectful to their other language

skills and inappropriately privileges English speakers above those who speak or sign

other languages. Community feedback to ORE consistently supports using other terms

than “LEP” to describe people with language access needs. For example, most people

in Vermont who speak Lingala, a language spoken in central Africa, also speak Swahili

and French. Labeling a trilingual person as “limited English proficient” simply because

the three languages they speak do not include English is disrespectful to their

considerable linguistic talents. Furthermore, the legal and ethical responsibility for

providing language access services falls on the State. Using the alternate phrases

“people with language access needs” or “people with communication access needs”

reminds State employees of our responsibility to provide those services.

“People who speak or sign languages other than English,” “people with

communication access needs,” and “people with language access needs” are terms

used throughout this document except when referencing materials created by other

entities that use the term “LEP.” “People who speak or sign languages other than

English” includes people who use American Sign Language (ASL) or any other signed

language. “People with communication access needs” or “people with language access

needs” may be more appropriate than “people who speak or sign languages other than

English” in situations when one is describing specific challenges faced by people who

have limited comprehension of spoken or written English and/or people who require

additional supportive technology to interact with English communications. Find more

information on specific terms for D/deaf, DeafBlind/deafblind, late deafened, DeafPlus,

DeafDisabled, and Hard of Hearing people at the Department of Disabilities, Aging &

Independent Living (DAIL) website here: Hearing Terminology

2

. (Siegel, 2022).

RECOMMENDATIONS:

Discontinue use of the terms “limited English proficient” or “LEP” whenever

possible in favor of terms that do not perpetuate bias against people who speak

or sign languages other than English.

Utilize the resources on respectful language available from DAIL and the

Vermont Department of Human Resources Center for Achievement in Public

Service (CAPS) when writing about people who are D/deaf, DeafBlind/deafblind,

late deafened, DeafPlus, DeafDisabled, or Hard of Hearing.

LEARN MORE: For resources on language and terminology, see Appendix B.

2

Full URL: https://dail.vermont.gov/sites/dail/files/documents/HearingTerminology.pdf

INTRODUCTION 16 OF 96

INTRODUCTION

Pursuant to 3 V.S.A. §5003, the Office of Racial Equity (ORE) is charged with

“identifying and remediating systemic racial bias within State government” (No. 142,

2022). The ORE’s comprehensive research into language access services as currently

provided by the State of Vermont revealed deficiencies in key areas for ensuring

communicative autonomy for all of Vermont’s residents and visitors.

Language access is regulated on the federal level as a civil rights issue. All

programs that receive federal funding must provide language access services to comply

with federal civil rights legislation and rules, including but not limited to Section 601 of

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Federal Executive Order 13166 (U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services, 2003). It is imperative that the State

broaden its language access protocols from a federal compliance perspective to prevent

further expenses related to noncompliance. The federal government has taken legal

action against two entities within the Vermont State government due to noncompliance

with federal language access regulations within the past 3 years. Additional legal

expenses related to language access noncompliance will continue to compound unless

there are major policy changes and revenue allocations to support language access.

More importantly, it is imperative the State strengthen its provision of language access

services as a moral and social good.

In 2022, ORE conducted community outreach to inform best practices for

language access in Vermont. ORE used the community outreach process to gain insight

into the language access needs and barriers faced by people who speak or sign

languages other than English in the state of Vermont. ORE hosted two community

conversation sessions in 2022. The first session was a “hybrid” event with in-person and

remote participation via ZoomGov. The second session was held fully virtual via

ZoomGov to balance participant convenience and ongoing public health concerns

related to the COVID-19 (coronavirus disease identified in 2019) pandemic. The first

session held on April 13, 2022 was a brainstorming session with facilitated discussions

of current language access needs, gaps in State-provided services, and suggestions for

improvements that could be made to current language access services.

LEARN MORE: For a summary document from the April 2022 brainstorming session, see

Appendix F.

In addition to the community feedback gathered at the April 2022 brainstorming

session, ORE also collected feedback and comments through an online form for several

weeks after the convening. These two collections of feedback were used to create a list

of 26 comprehensive recommendations for improving language access services in the

State of Vermont. The ORE presented the recommendations to the community

members and State employees on August 31, 2022. ORE accepted feedback at this

second session, and also through an online form for an additional two weeks after the

second session.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION 17 OF 96

ORE conducted a research project to calculate the expected cost of translating

all the vital documents in the Executive Branch of the Vermont state government. The

vital document research project documented significant gaps in federal compliance with

regards to the translation of vital documents and the lack of notice of the availability of

free language access services by many State entities. The details and conclusions of

the vital document cost estimate project, including the methodology for estimating the

cost of translating individual documents, can be found in Appendix G .

PLAN COMPONENTS & FEDERAL STANDARDS 18 OF 96

LANGUAGE ACCESS PLAN COMPONENTS AND FEDERAL STANDARDS

Basic Components of a Language Access Plan

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (2022) indicate that all standard,

federally compliant language access plans contain a description of five basic

components:

1. Needs assessment of the population served by a state agency,

2. Language services to be provided by the agency,

3. Plans to notify clients of the availability of language services,

4. Training plans for agency employees on its policies and procedures for providing

language access, and

5. Evaluation plans for monitoring and updating language access procedures over

time.

In addition to the five basic components, State agencies must create opportunities for

people with language access needs to provide comment on the agency’s language

access plan (Federal Coordination and Compliance Section Civil Rights Division, 2011).

LEARN MORE: For more guidance on conducting equitable outreach, see Appendix B.

LEARN MORE: For ORE’s recommended minimum standards, see Appendix D.

Federal Requirements for the Provision of Language Access Services

Four factors determine whether it is necessary for federal compliance to provide

language access services to people who speak or sign languages other than English

(U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2003).

PLAN COMPONENTS & FEDERAL STANDARDS

PLAN COMPONENTS & FEDERAL STANDARDS 19 OF 96

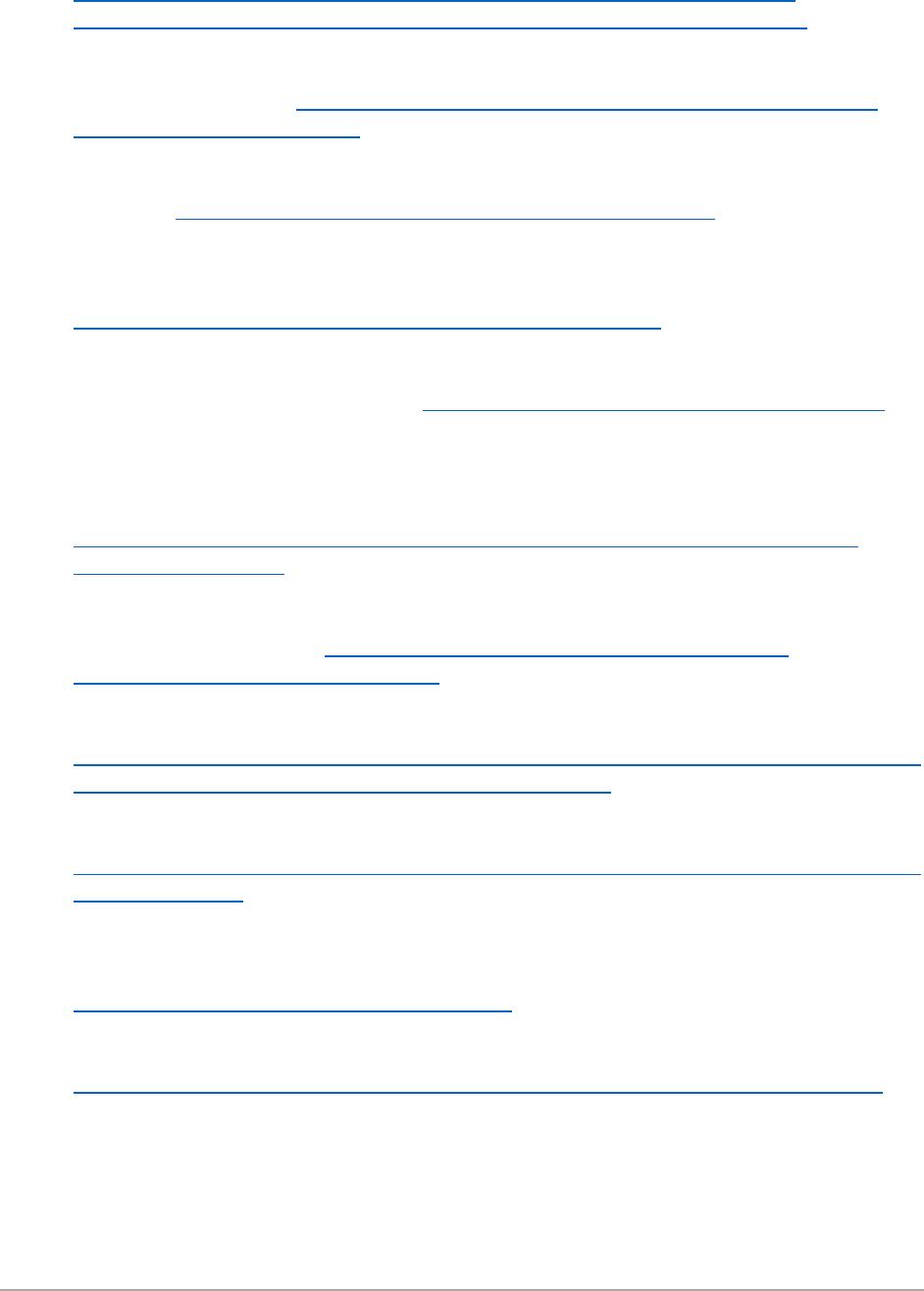

Figure 1. Four-factor analysis for determining language access requirements under

federal civil rights regulations

Figure 1 describes the four factors to consider when planning for language access services. The

four-factor test describes how to determine what level of language access services, if any, are

required to meet minimum non-discrimination/civil rights guidelines for recipients of federal

funding. Summarized from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services “Guidance to

Federal Financial Assistance Recipients Regarding Title VI Prohibition Against National Origin

Discrimination Affecting Limited English Proficient Persons” (U.S. Department of Health and

Human Services, 2003).

When deciding how to apply the four-factor test, it is necessary to recognize the

importance of communicative autonomy as a basic principle of human rights. The four-

factor test helps achieve compliance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Law of 1964 and

other applicable federal regulations. However, simply maintaining the minimum

compliance with federal requirements does not guarantee that clients are being served

equitably or with justice in mind. Community members and State employees who

participated in language access meetings with ORE expressed concern that Factor 4 (a

lack of resources) has been used as an excuse not to provide equitable language

access services in the past (Davis, 2022). When resources are limited, it is imperative

that language access services be prioritized on the principles of equity and justice. See

Appendix B: Additional Resources for further information about diversity, equity,

inclusion, and justice in language access.

01

How many people with communication access needs are served by the

program, activity, or service? What proportion of the total number of

people served is comprised of people with communication access needs?

02

How often do people with communication access needs

interact with the program, activity, or service?

04

What resources are available to the entity providing the

program, activity, or service? Would providing certain types

of language access services be prohibitively expensive?

03

What is the nature of the program, activity, or service?

How important is the program, activity, or service to the lives

of people served?

PLAN COMPONENTS & FEDERAL STANDARDS 20 OF 96

Figure 2. Four Steps to Planning for the Implementation of Language Access

Services

Figure 2. Four Steps to Planning for the Implementation of Language Access Services shows

the four preliminary steps that must be taken before implementing language access services

summarized from “Language Access Assessment and Planning Tool for Federally Conducted

and Federally Assisted Programs” (Federal Coordination and Compliance Section, 2011). A full

description of these steps, checklist, and considerations for each is available at Language

Access Assessment and Planning Tool for Federally Conducted and Federally Assisted

Programs (Federal Coordination and Compliance Section, 2011).

One resource available to State entities is the State of Vermont Chief

Performance Office

3

, whose staff can assist with questions relating to performance

measurement and results-based accountability (Chief Performance Office, 2022).

VITAL DOCUMENTS

Vital documents are public-facing, non-confidential documents of significant

importance to the clients of a program or service according to the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services (HHS) (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,

2003). Vital documents contain information that is essential for ensuring meaningful

access to the programs or services of an agency (Vermont Judiciary, 2021c). Examples

from HHS of common vital documents include:

Informed consent forms or complaint forms

Program intake forms that collect participants’ information

3

See Appendix B: Additional Resources for more information on the Chief Performance Office and

results-based accountability/continuous improvement frameworks for program evaluation.

ASSESS

Assess the number of

people with language

access needs currently

served by your agency

and which languages

are most commonly

spoken among your

clients with language

access needs.

IDENTIFY

Identify who will be

responsible for

implementing each

element of the

language access plan

within your agency.

Identify vital

documents that will

need to be translated.

DESCRIBE

Describe the

timeframe for

implementation.

Describe performance

measures that will

allow you to evaluate

the success of

language access

services in the future.

ADDRESS

Address any barriers

to implementing the

language access

services (for example,

insufficient staff

capacity, knowledge

gaps, and financial

resources needed for

implementation).

PLAN COMPONENTS & FEDERAL STANDARDS 21 OF 96

“Written notices of eligibility criteria, rights, denial, loss, or decreases in benefits

or services, actions affecting parental custody or child support, and other

hearings” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2003)

Documents or materials which notify people who speak or sign languages other

than English of the availability of language assistance services

“Written tests that do not assess English language competency, but test

competency for a particular license, job, or skill for which knowing English is not

required” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2003)

“Applications to participate in a recipient's program or activity or to receive

recipient benefits or services” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,

2003)

“documents required by law” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,

2015)

A plain-language version of a document can help to reduce translation costs by

shortening the document while preserving essential information. Plain-language

documents also assist people with cognitive or developmental disabilities in

understanding technical documents.

LEARN MORE: For more information on plain-language documents, see Appendix B.

SAFE HARBOR STANDARDS

“Safe harbor” refers to whether an entity covered by federal language access

regulations will be considered to have met the minimum requirements for compliance

when choosing which languages to translate their written materials into (U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services, 2003). Note that the safe harbor

guidelines only apply to choosing which languages to translate written materials

into, not to the federal requirement for providing meaningful access to people

who speak or sign languages other than English. Individual people must be

provided with meaningful access as requested, no matter how rare the language they

speak.

The guidelines for safe harbor provided by the U.S. Department of Health and

Human Services state that recipients of federal funds should provide written translation

when the recipient’s population that is eligible for services includes at least five percent

(5%) or one thousand (1,000) people who speak or sign a language other than English,

whichever is less (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2003). If there are

fewer than 50 people who speak a language, it is sufficient under safe harbor standards

to provide written notice of the right to receive spoken interpretation of the written

materials at no cost to the client (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,

2003).

It is challenging to evaluate which languages State entities must translate

documents into according to the federal safe harbor standards. According to the 2021

American Community Survey (ACS), the 5-year population estimate of the number of

PLAN COMPONENTS & FEDERAL STANDARDS 22 OF 96

Vermont residents who speak English less than

“very well” is 7,705 people, with a margin of error

of ±636 people. 7,705 people is approximately

1.3% of the total Vermont population (U.S.

Census Bureau, 2021a). Each individual

language spoken or signed may not have one

thousand speakers/signers living in Vermont.

The ACS 2021 5-year summary data does not

list the specific language spoken, only the

linguistic family (“Indo-European,” “Asian and

Pacific Islander,” or “other” languages) (U.S.

Census Bureau, 2021a).

The U.S. Census Bureau has released

detailed tables from the 2021 ACS 5-year

summary data listing the languages spoken by people in Vermont who speak a

language other than English at home, disaggregated by how many people speak

English “very well” or less than “very well” (U.S. Census Bureau, 2021b). The detailed

2021 ACS “Language Spoken at Home by Ability to Speak English for the Population 5

Years and Over” Vermont table can be found at the U.S. Census website here: 2021

ACS Languages Spoken at Home.

4

(U.S. Census Bureau, 2021b). However, ACS data

sets cannot be considered a complete population count.

5

Even the detailed 2021 ACS

“Language Spoken at Home by Ability to Speak English for the Population 5 Years and

Over” Vermont table groups all Central, Eastern, and Southern African languages into

one category, which precludes detailed analysis of the population size needed for

evaluating safe harbor provisions regarding vital document translation.

The ACS data, while readily available online, should not be the only source of

data used to evaluate the number of people who speak or sign languages other than

English in Vermont. The ACS likely undercounts the number of households where

people speak Spanish or an indigenous language of Latin America and are

undocumented. People who are undocumented may not feel comfortable responding to

4

Full URL: https://data.census.gov/table?q=B16001&g=0400000US50&tid=ACSDT5Y2021.B16001

5

ACS data are estimates based on head of household reports, not actual counts of population size (U.S.

Census Bureau, 2017). Household population sampling is conducted by asking a sample of the

householders in the State to answer questions about the demographic characteristics of all the people

living in the same housing unit. A householder is defined as, “the person (or one of the people) in whose

name the housing unit is owned or rented (maintained) or, if there is no such person, any adult member,

excluding roomers, boarders, or paid employees” (U.S. Census Bureau, 2021c). Notably, the ACS only

measures head of household’s gender by the sex labels of “male” or “female,” which is insufficient to

describe the gender diversity present in legal documents that are available to Vermonters. Vermont

residents have the option to choose X as a non-binary gender marker on their identification documents

including birth certificates and drivers’ licenses, pursuant to 18 V.S.A. §5112 and relevant Department of

Motor Vehicles rules and regulations (Vermont General Assembly, 2022). The ACS is significantly lacking

in the ability to identify family structures outside of cisgender/heteronormative and White American

nuclear family structures and has no mechanism to identify transgender/gender-diverse people.

PLAN COMPONENTS & FEDERAL STANDARDS 23 OF 96

the ACS due to their immigration status or because of a language barrier between the

person administering the survey and the potential respondent. There are approximately

1,000-1,200 people from Latin America living in Vermont who work in the agricultural

and tourism industries, some of whom are undocumented (Mares & Kolovos, 2021, p.

202). Most speak Spanish, but some speak indigenous languages of Latin America

(Mares & Kolovos, 2021). State entities should always plan to translate vital documents

and other translated materials into Spanish.

Members of the Deaf community who participated in the ORE language access

conversations gave consistent feedback that ASL is frequently neglected as a language

commonly used by many Vermonters. People who sign ASL often consider English to

be a second language and may have difficulty understanding written English compared

to their fluency in ASL. ASL has different grammatical structure and vocabulary from

spoken or written English (Siegel, n.d.). The ADA accessibility requirement to provide

effective communication assistance to people who sign languages applies regardless of

safe harbor standards regarding the number of ASL signers in Vermont. Therefore,

ORE recommends that ASL-translated versions of vital documents be created to

support language access and ADA compliance for people who sign ASL.

All State entities must evaluate which languages are spoken or signed by the

people who interact with their programs and services on a regular basis when planning

for language access implementation. The process of deciding which languages to

translate vital documents into should be based on a careful evaluation of the languages

most used on a program-by-program or department-level basis.

LEARN MORE: For further discussion of population data and resources for evaluating

population size, see Appendix C.

LEARN MORE: For further discussion of how to evaluate costs related to vital document

translation and the maintenance costs of translated vital documents, see Appendix G.

NOTICES OF THE AVAILABILITY OF LANGUAGE SERVICES NOTICES

Any entity that receives federal funding is required to send a notice of the availability

of language services with any communications that require a response (U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services, 2003). ORE recommends translating

notices of the availability of language assistance into the 13 languages that comprise

the Vermont Agency of Human Services (AHS) LEP Committee language list plus the

languages likely to be needed based on recent population residency trends. The 14

languages recommended for vital document translation, listed in alphabetical order, are:

Arabic

Bosnian

Burmese

Dari

French

6

Used here, Simplified Chinese is considered the written form of Mandarin Chinese.

Kirundi

Simplified Chinese

6

Nepali

Pashto

Somali

Spanish

Swahili

Ukrainian

Vietnamese

PLAN COMPONENTS & FEDERAL STANDARDS 24 OF 96

ORE further recommends that

On all written communications, include a notice in English of the availability of

accessible telecommunications resources for people who use assistive

technology to communicate.

On all State websites and electronic communications, include a video of an ASL

signer notifying people who sign ASL of the availability of free language services.

NOTE: ORE does not recommend that State entities simply rely on the AHS LEP

Committee’s list of languages to determine which languages to translate vital

documents into.

NOTE: Program-level or department-level evaluation of the languages spoken by clients

with language access needs is necessary to decide which languages to translate vital

documents into. Demand for language services will likely increase as State entities take

responsibility for including notices of the availability of language services in mailings.

LEARN MORE: For additional discussion of the AHS LEP Committee language list, see

Appendix C.

LANGUAGE ACCESS OPERATIONS MANUALS

The second component of a language access plan is a separate language

access operations manual. The language access operations manual contains all the

details needed for State employees to understand how to provide language access

services. The language access operations manual is an essential tool for training staff

to provide access to language services in a timely, considerate, and equitable manner.

Some examples of information that could be included in the language access operations

manual include the name and phone number of contracted interpretation service

providers along with the billing codes for the department See Appendix B: Additional

Resources for a link to the Buildings and General Services (BGS) list of contracted

State language services providers and an example of a State language access

operation manual (Vermont Judiciary, 2021b).

The Vermont Department of Labor (VDOL) created its language access

operations manual in the form of a SharePoint site where VDOL employees can easily

access all information needed to obtain language services on behalf of their clients.

VDOL's SharePoint site has a link to a feedback form, so that a VDOL service provider

can share constructive critique or praise following an encounter with an interpreter.

EXAMPLE: For a deeper look at the VDOL language access operations manual website

and selected guidelines for working with interpreters, see Appendix E.

PLAN COMPONENTS & FEDERAL STANDARDS 25 OF 96

Using the SharePoint suite of tools is an excellent way to make language access

operations manuals easily accessible to any State employee with computer access.

State employees should maintain a printed copy of the language access operations

manual in case of power outages or internet service disruptions.

FINDINGS & RECOMMENDATIONS 26 OF 96

FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The following recommendations were generated from the community language access

conversations held in April and August 2022 in combination with research conducted by

ORE staff. See Appendix F: April 2022 Brainstorming Meeting Summary Document for

the summary notes from the April 2022 brainstorming meeting and a detailed list of the

community-based organizations who were represented at the meeting. The findings and

recommendations are grouped into 6 categories:

Values, Framework, and Culture

Data, Evaluation, and Reporting

Operations and Staff Protocols

Technology and Resources

Professional Development and Qualifications

ADA Compliance for People who Sign Languages and/or People with Disabilities

HOW TO READ THE FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The findings and recommendations below are not listed in order of relative importance;

they are grouped by topic areas as identified above.

F Y.Y

Findings are numbered for easy reference.

R Z.Z.Z

Recommendations are numbered for easy reference. One finding might

have multiple recommendations associated with it.

E/L/J

Identifies which branch(es) of government are the subject of the

recommendation.

E – Executive branch L – Legislative branch J – Judiciary branch

Note that the Executive branch includes more than the agencies under the

direction of the Governor. Additionally, any State government entities that

exist outside these three branches are still strongly encouraged to

implement as many of these recommendations as feasible to ensure

adequate language access for the communities they serve.

1. Values, Framework, and Culture

FINDING 1.A:

F 1.A

The State of Vermont has no unified values statement regarding language

access.

Recommendations:

R 1.A.1

E/L/J

Draft & publicize an official values statement that State government is

committed to providing equitable language access services.

FINDINGS & RECOMMENDATIONS

FINDINGS & RECOMMENDATIONS 27 OF 96

R 1.A.2

E/L

Require State agencies to adopt a language access plan that is at

least as rigorous as the model minimum language access plan

provided in Appendix D of this report.

R 1.A.3

E

Determine whether to create a central point of contact for any person

who needs language services from any State agency to contact for

language assistance.

7

EXAMPLE: For a sample policy statement on language assistance, see Appendix D.

FINDING 1.B:

F 1.B

Language service work, including translation and interpretation, is often

undervalued and undercompensated. Language service providers in Vermont

frequently take on multiple employment positions to support themselves

financially. Translation and interpretation are highly skilled jobs that require

many hours of training for proficiency, in addition to the skills of acting as

cultural brokers for their clients (Flores et. al, 2012; Feng, 2021; Davis, 2022).

Recommendation:

R 1.B.1

E/L

Increase compensation for BGS-contracted language assistance

service providers to allow them to pay their employees a living wage.

8

2. Data, Evaluation, and Reporting:

FINDING 2.A:

F 2.A

State agencies will have unique needs for implementing language access

services based on their duties and the populations they interact with most. The

7

There was some discussion between community members and State employees who were present at

the ORE language access conversations about where the designated central point of contact for

language access services should be housed. Many community members expressed interest in seeing the

ORE take on responsibility for being a centralized point of contact for people with language access needs

across the entire Executive Branch. Other State employees present at the discussions noted the difficulty

of relying on ORE to serve as the central point of contact when ORE staff may not be aware of day-to-day

operations at the programmatic level in all other Executive Branch agencies, as well as the expansive

workload involved with being the central point of contact for all other agencies. Some State employees

suggested that the Agency of Human Services (AHS) be the central point of contact as AHS already

provides a great deal of language access services. Others noted the tendency for equity-related work to

be given to the ORE rather than being treated as a shared responsibility for all government entities.

8

Community feedback at the April 2022 language access brainstorming conversation indicated that

medical interpreters are undercompensated for the highly skilled and extremely important function they

serve. Commenting on ways to increase compensation for medical interpreters who are paid by health

care systems that are not State government entities is outside of the scope of this report but is an

important and closely related issue. Health care systems should examine their reimbursement policies

related to interpretation and translation, including the ways in which they advocate to state and federal

governments about the low Medicaid reimbursement rate for medical interpreter services. Additional

information on considerations for health care costs is available at

https://www.vtlegalaid.org/sites/default/files/HCA_Policy_Paper_Cost_Shift_Fact_Or_Fiction.pdf.

FINDINGS & RECOMMENDATIONS 28 OF 96

details of each agency’s language access plan may vary by agency or time

period.

Recommendations:

R 2.A.1

E/L/J

Require that every State agency file a copy of its language access plan

with ORE to ensure that minimum recommended best practices are

met statewide.

R 2.A.2

E/L/J

Require that every State entity with a language access plan evaluate

and revise its plans on a defined schedule. ORE suggests a schedule

of once per year for the first 5 years following implementation, then at

least once every 5 years thereafter.

FINDINGS 2.B AND 2.C:

F 2.B

Tracking expenditures and evaluating programmatic needs related to language

access services is extremely difficult based on current billing practices, which

frequently do not specify the languages in which services were provided or the

type of language assistance that was provided.

F 2.C

Limited data are available to help quantify the number of people in Vermont

who speak or sign languages other than English.

LEARN MORE: For additional discussion about population estimates of people who speak

or sign languages other than English in Vermont, see “Vital Documents” and

Appendix C.

LEARN MORE: For a narrative summary of the challenges associated with tracking

language services expenses, see Appendix G.

Recommendations:

R 2.B.1

E/L/J

Train State employees on how to use specific accounting codes to bill

for different types of language services (such as interpretation and

translation) to aid in tracking language access service expenditures.

R 2.B.2

E/L/J

Determine the best way to establish a general fund allotment, internal

service fund, or other funding mechanism specifically for language

access implementation.

R 2.B.3

E/L/J

Create a finalized cost estimate for vital document translation costs on

a programmatic or department level to assist with agency-level budget

development and tracking.

R 2.B.4

E/L/J

Track any costs relating to updating existing vital documents that have

already been translated, and costs related to translating existing

translated vital documents into additional languages.

R 2.C.1

E/L/J

Require all State entities to maintain records of the type of language

service provided and the languages in which the services were

provided to facilitate evaluation of language access service. Ensure

FINDINGS & RECOMMENDATIONS 29 OF 96

that personally identifiable information of people with language access

needs (such as name and date of birth) are not stored in the same data

sets as the tracking of language access services expenses to protect

the privacy of people with language access needs.

3. Operations and Staff Protocols

FINDING 3.A:

F 3.A

Many State agencies, departments, and divisions do not possess adequate

financial resources or dedicated staffing to implement the language access

plans required by federal regulations. Further, the utilization of language

access services is likely to increase as State agencies communicate more

effectively to inform people with language access needs of the availability of

language assistance services.

Recommendations:

R 3.A.1

E/L/J

Evaluate whether additional staff positions are necessary to support

equitable language access program implementation.

R 3.A.2

E/L/J

At a minimum, designate at least one primary State employee and a

secondary State employee to be the point of contact for language

access in each department.

R 3.A.3

E/L

Permit agencies to request additional positions to ensure sufficient staff

resources exist for a robust language access program, particularly if

agencies provide services that are important to the health and safety of

Vermont residents and visitors.

R 3.A.4

E

Permit agencies to exceed level funding budget requests if the funds

are related to vital document translation or other language access

service needs.

FINDINGS 3.B AND 3.C:

F 3.B

State agencies do not uniformly distribute information about how to access free

language access services when mailing notices that require a response from

the recipient or contain essential information. Mailing notices of the availability

of free interpretation services is necessary to ensure that people with language

access needs can respond to notices of important information related to State

services. Notices of language assistance are a key component of the

requirements for compliance with federal language access regulations (U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services, 2003).

F 3.C

Some people who speak or sign languages other than English are not aware of

the federal requirement that the State pay for language access services on

their behalf. They may be hesitant to request language services because of a

lack of personal financial resources (Davis, 2022).

FINDINGS & RECOMMENDATIONS 30 OF 96

Recommendations:

R 3.B.1

E/L/J

In all State mailings that require a response or notify the recipient of

important information, include a page with instructions in the 14

recommended languages on how to access language services.

R 3.C.1

E/L/J

Ensure all notices of language assistance services inform recipients

that the services are free of charge for the person receiving services.

EXAMPLE: See an example of a language assistance notice page at the Vermont

Department for Children and Families, Economic Services Division website here: BSC

Interpretation Line.

9

LEARN MORE: For additional discussion of the ORE-recommended languages to translate

notices of language assistance service, see “Vital Documents.”

FINDINGS 3.D AND 3.E:

F 3.D

Vital documents are not routinely translated into languages other than English

across State entities.

F 3.E

Some vital documents may be too long or too technical for the average reader

to understand, even after translation.

NOTE: Research into which Legislative branch documents constitute vital documents

suggests that notices of the availability of language assistance and any “documents

required by law” may fall within the definition of “vital document” according to HHS

guidelines (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2015). Further legal

analysis by the Office of Legislative Counsel is needed to inform the Legislature’s vital

document translation process.

Recommendations:

R 3.D.1

E/L/J

Identify all vital documents at each State agency and in the Legislative

and Judiciary branches and translate them into the most commonly

spoken languages of the people who access each entity’s services.

R 3.D.2

E/L/J

Ensure vital documents are periodically updated as the information

within them changes. Periodic reviews of language access policies and

programs should include a review of vital documents to ensure they are

up to date.

R 3.D.3

E/L/J

Designate a staff person or team of State employees to oversee

keeping vital documents up to date within each department.

R 3.D.4

E/L/J

Track expenditures related to keeping vital documents up to date as

part of overall language access expenditure tracking.

9

Full URL: https://outside.vermont.gov/dept/DCF/Shared%20Documents/ESD/Contacts/BSC-

Interpretation-Line.pdf

FINDINGS & RECOMMENDATIONS 31 OF 96

R 3.E.1

E/L/J

Create plain-language versions of very long or technical vital

documents before translating them.

LEARN MORE: For more information on plain-language summaries, see Appendix B.

FINDING 3.F:

F 3.F

The State can better utilize existing software systems to alert State employees

of the need to arrange interpretation services when working with people who

speak or sign languages other than English.

Recommendations:

R 3.F.1

E/L/J

Audit all State records management software systems for their ability to

identify people who need language access services.

R 3.F.2

E/L/J

Configure records management software systems to alert State

employees to arrange for interpretation services or other language

assistance services prior to meetings with the clients who need them.

FINDING 3.G:

F 3.G

Most State employees only speak English, which can be a barrier to language

access in State offices where services are regularly provided in-person (Davis,

2022).

Recommendations:

R 3.G.1

E/L/J

At all public-facing offices, utilize “I Speak” cards with a standard

written list of yes/no questions in VT’s most commonly spoken

languages, plus an electronic device with a video ASL version to

facilitate providing language access services.

R 3.G.2

E/L/J

Train State employees to use "I Speak" cards and to access telephonic

interpretation services from State-contracted language service

providers when they need to serve people with language access needs.

EXAMPLE: For links to examples of “I Speak” cards, see Appendix B.

EXAMPLE: For an example of a CAPS training course on interactions with people with

hearing loss, see Appendix B.

FINDINGS 3.H AND 3.I:

F 3.H

Having multilingual State employees interpret for clients could create conflicts

of interest or other ethical or privacy concerns for clients or State employees.

F 3.I

There is no standard operating procedure to assess the sufficiency of the