Issues in Educational Research, 27(4), 2017 736

!

!

Developing and validating a metacognitive writing

questionnaire for EFL learners

Majid Farahian

Department of ELT, College of Literature and Humanities, Kermanshah Branch, Islamic Azad University, Kermanshah, Iran

In an attempt to develop a metacognitive writing questionnaire, Farahian (2015)

conducted a study which was based on the results obtained from a semi-structured

interview (Maftoon, Birjandi & Farahian, 2014). After running various exploratory factor

analyses (EFA) to validate the questionnaire two general scales of knowledge and

regulation of cognition emerged; however, regarding the subscales of knowledge and

regulation of cognition no clear pattern was found. As such, in the present study a

confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was run to refine the scale and construct the final

questionnaire. The findings led to a hypothesised model comprising two factors of

knowledge of cognition and regulation of cognition with ten subcategories represented in

a 36-item questionnaire.

Introduction

Although the historical background of metacognition, as well as self-regulation, can be

traced back to James, Piaget and Vygotsky (Fox & Riconscente, 2008), it was not until the

1970s that the concept was shaped, and the term metacognition was coined. Flavell (1987)

suggested that metacognitive knowledge is “the part of one’s acquired world knowledge

that has to do with cognitive (or perhaps better, psychological) matters” (p. 21). As a

matter of fact, it includes the individual’s perspective of one’s own cognitive abilities, as

well as others.

After the emergence of process-oriented approaches in writing, notably that of Hayes and

Flower (1980), the vital role of metacognition in the writing process has been widely

acknowledged. Various cognitive processes refer to the crucial role of self-regulatory and

decision making processes which improve writing performance. The emphasis on the

critical role of metacognition has been so great that Hayes and Flower argued that “a great

part of the skill in writing is the ability to monitor and direct one’s own composing

process” (p. 39). Hacker et al. (2009), having the same approach, defined writing as applied

metacognition.

Process-oriented theories of writing conceive of writing as a problem solving activity. The

more one is equipped with higher order processing skills, the more he or she will be

capable of acting successfully in problem solving situations. In other words, it can be

concluded that for a recursive goal directed process to function properly, monitoring a

mechanism for “management of topical, rhetorical and strategic knowledge” (Hawkins,

2007, p. 6) is crucial.

The role of metacognition is also emphasised in the post-process approaches to writing

(Hawkins, 2007), which have criticised cognitive process-oriented approaches to writing as

being “overly individualistic, reductive, and de-contextualized" (p.48). Socio-cognitive

Farahian 737

models and genre-based approaches, for example, have such a stance. It should be noted

that genre-based approaches give a pivotal role to metacognitive processes (Yeh, 2014)

which “have as their object knowledge of genre, discourse, and rhetorical aspects of

academic texts” (Negretti & Kuteeva, 2011). These approaches have no choice but to

admit that apart from the interplay of the effect of social context, affect, and cognition,

metacognition has a decisive role in writing.

Metacognition has also found its place in second language studies (e.g., Blasco, 2016;

Gustilo & Magno, 2015). Wenden (1998), argued that metacognitive knowledge “is a

prerequisite for the self-regulation of language learning: it informs planning decisions

taken at the outset of learning and the monitoring processes that regulate completion of a

learning task…” (p. 528). Apart from its role in different language learning skills,

metacognitive knowledge has been recognised as a significant attribute affecting the

process, as well as the product in second language writing (Wang, Spencer & Xing, 2009;

Zimmerman & Bandura, 1994). Research findings show that metacognitive awareness is a

factor which distinguishes poor from skilled writers (Victori, 1999). The metacognitive

growth of second language learners apart from their ethnic, cultural, and linguistic

backgrounds positively correlates with their writing performance (Kasper, 1997).

Metacognition is given even higher credit by some scholars (e.g., Hacker, Keener &

Kircher, 2009) who claim that the writing process from the beginning to the end is an act

of metacognitive behaviour. The reason offered for such an assertion is that the

knowledge of metacognition and its manipulation should be with writers every second

they are involved in the writing.

Parallel to inquiry into the role of the metacognition in learning, a large number of

research studies have shown interest in the measurement of metacognitive knowledge in

second language learning as well. As such, tools for assessing metacognition in second

reading and listening, Metacognitive Awareness Listening Questionnaire (e.g., Vandergrift et al.,

2006) and Metacognitive Awareness of Reading Strategies Inventory (Mokhtari & Reichard, 2002)

were developed; however, despite such a growth of interest in developing measures of

metacognition in second language learning, scant attention has been given to the

development of measures of metacognition in second language/foreign language writing,

though a few studies have dealt with metacognition in second language/foreign language

writing (Kasper 1997; Sperling et al., 2002; Victori, 1999). Research findings identify

metacognitive awareness as a factor which distinguishes poor from skilled writers (Victori,

1999). It has also been found that metacognitive knowledge of second language learners

correlates highly with their writing performance (Kasper, 1997). Metacognition has such

an important role in writing that it has been recognised as an act of metacognitive

behaviour (Hacker et al., 2009). The only study, to the researcher’s best knowledge, which

has attempted to develop a metacognitive knowledge questionnaire on writing, was by

Yanyan (2010), which was based on Flavell’s (1979) model of metacognition including

person, task and strategic knowledge. This turns out to be a limitation of the study as the

framework chosen by Yanyan did not adequately cover the related theoretical assumptions

such as the recent two-dimensional framework of metacognition (e.g., Brown et al., 1983;

Shraw & Dennison, 1994). Besides, there is no report on the validation of the

questionnaire.

738 Developing and validating a metacognitive writing questionnaire for EFL learners

Since measuring metacognition as a general construct for all contexts is very demanding

and may yield inaccurate findings, measures of metacognition have focused on narrower,

domain-specific areas. To this end, the present study, as a follow-up study for Farahian

(2015), aimed to assess the results obtained from factor analysis and refine the scale.

Accordingly, this study addressed the following research question:

Does the MAWQ (Metacognitive Awareness Writing Questionnaire) show good

fit indices as measured by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)?

Method

As reported in Farahian (2015), although the predicted components formed two general

factors of knowledge and regulation of cognition, the results obtained from exploratory

factor analysis (EFA) did not render reliable factors of MAWQ; therefore, structural

equation modeling (SEM) in AMOS22 (Statistics Solutions, n.d.) was conducted to

investigate the factor structure of the construct. Similar to the steps taken in EFA, first,

the construct validity of the knowledge of cognition was probed. Unlike EFA which did

not allow the researchers to have control over the number of desired factors and their

loading patterns, the CFA begins with a-priori model specified by the researchers and then

tries to support or reject the model.

Participants

The study was conducted in February 2014. The participants were 524 Iranian university

EFL students majoring in different fields of study in English language, including teaching

English, translation, and literature. The participants were selected using convenience

sampling from different universities.

Procedure

As the first step, the participants were interviewed (see Maftoon, Birjandi & Farahian,

2014). A list of statements was generated based on the content analysis of the participants’

responses. Following the inductive data analysis and after the emergence of some

categories, the deductive analysis as the confirmatory stage was adopted. Based on Patton

(2002) “generating theoretical propositions or formal hypotheses after inductively

identifying categories is considered deductive analysis…” (p. 454). At this stage, the

emerged categories were compared and contrasted to the existing categories in the field

(Brown et al., 1983; Schraw & Dennison, 1994; Shraw & Moshman, 1995). The purpose

was to see if the components of metacognitive awareness of the participating Iranian EFL

learners mirrored the literature. As a result, a classification of metacognitive awareness of

Iranian EFL learners emerged (Table 1).

Farahian 739

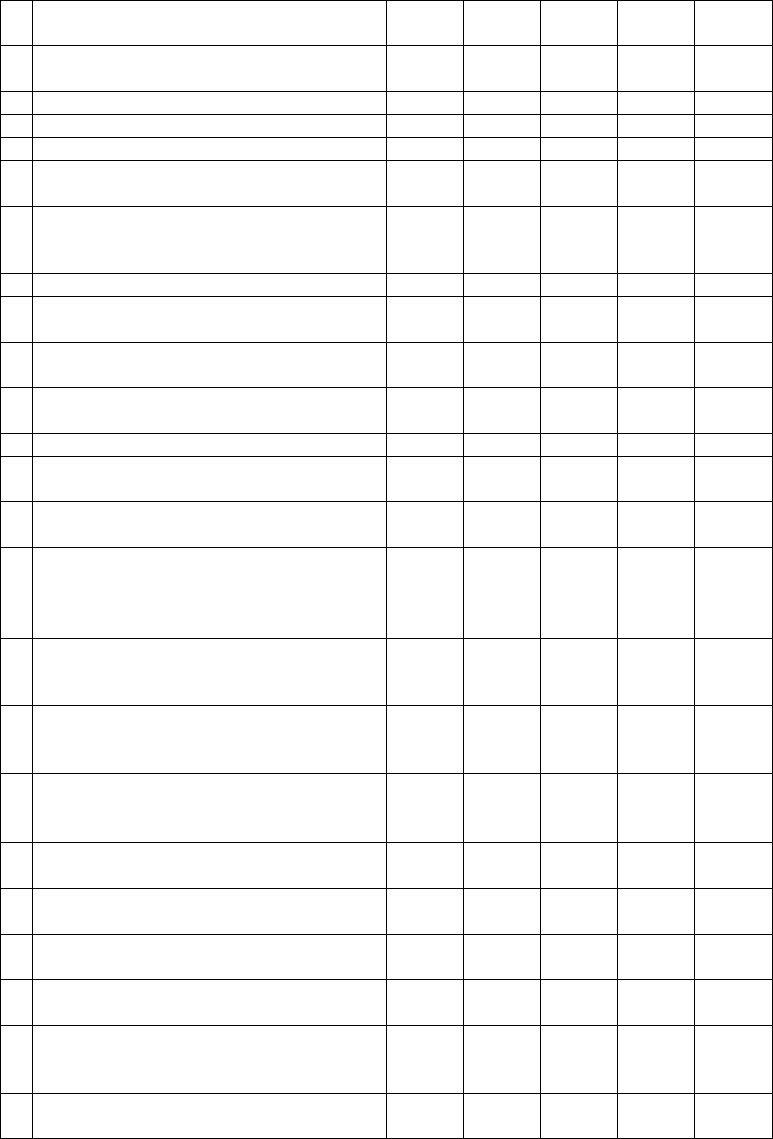

Table 1: The framework for metacognitive awareness writing knowledge

A: Knowledge of cognition

1. Declarative knowledge (person)

Self-concept and self-efficacy

General facts and opinion

mental translation

the effect of reading in FL

2. Declarative knowledge (task knowledge)

3. Procedural knowledge

4. Conditional knowledge

B: Regulation of cognition

1. Planning and drafting

Audience consideration

2. Monitoring

3. General online strategies

Allocating time and place

Avoidance

Attention

Asking for help

Translation

4. Revision

5. Evaluation

Adapted from Maftoon, Birjandi & Farahian (2014, p. 48).

Following the preparation of the initial item pools they were checked for content validity

by five experts. The resultant list of items was subjected to a pilot test with twenty

participants, who were asked to identify ambiguous items. They were also asked to write

their comments regarding the items. After receiving the feedback the list of statements

was again revised. The questionnaire was translated by a professional translator into

Persian to make sure that the participants’ limited language proficiency in English would

not negatively affect their responses. After the preliminary analyses of reliability and

testing assumptions a list of statements was then developed. To validate the questionnaire,

EFA and CFA were run.

Findings and discussion

As it was reported by Farahian (2015), the reliability indices were acceptable ranging from

.67 to .91. The obtained result from EFA showed a two factor model for metacognitive

awareness. However, no clear pattern emerged regarding the sub-components. Therefore,

it was thought that a CFA may help researcher fine-tune the obtained results.

Trait structures of knowledge of cognition

Figure 1 displays the trait structures of the components of the knowledge of cognition

questionnaire in standardised units. The knowledge of cognition – as represented by an

oval at the middle of the diagram – has five components each of which has a number of

items which are displayed through smaller sized ovals. It should be noted that three items,

namely, attention, translation, and audience consideration were dropped from the model

because they were the only observed indicators for the latent variables.

740 Developing and validating a metacognitive writing questionnaire for EFL learners

Figure 1: Knowledge of cognition model (standardised estimates)

The model for knowledge of cognition shows that all of the paths between observed and

or latent variables were significant (p < .001), except for GeneKC3 and GeneKC4 (two

items related to general section of knowledge of cognition) which made non-significant

contributions to the model (p > .05).The standardised regression coefficients for the

above mentioned two variables were lower than .30, the minimum acceptable value.

Figure 2 clearly shows the trait structures of knowledge of cognition after removing the

two non-significant observed variables. In the revised model, all the paths between

observed and /or latent variables were significant (p < .001). Moreover, the paths in

standardised units all of the standardised regression coefficients were higher than .30.

The model fit indices showed a good fit for the revised model. However, it is noteworthy

that although the chi-square test was significant (χ

2

(45) = 284.60, p < .05), the large

sample size might have resulted in the significance value. The ratios of the chi-square over

the degrees of freedom (1.72 < 3) also indicated that the model enjoyed a good fit. The

RMSEA value of .033 and its 95 percent confidence intervals (.030 and .045) were all

lower than .05, another indication of the fit of the revised model. The p-close fit value of

.998 (> .05) indicated the knowledge of cognition enjoyed a good fit. The CFI (.97 > .95)

also showed the good fit of the revised model.

Farahian 741

Figure 2: Revised knowledge of cognition model (standardised estimates)

Trait structures of recognition of cognition

Figure 3 shows the trait structures of the components of the recognition of cognition

questionnaire in standardised units. The recognition of cognition, as shown by an oval in

the middle of the diagram, has eight components each of which has a number of items

shown by rectangles.

Unlike the knowledge of cognition model, the recognition of cognition needs a number of

revisions. Based on the results, eight variables were deleted, namely Plan5, Plan7, AsH1,

AsH2, GeneST2, GeneST 4, Eval2 and Monit5, due to their non-significant and / or low

contribution to the model. Unlike the expectation, this model did represent a good fit to

the data since none of the fit indices were at the recommended levels; therefore, the

regulation of cognition model was revised twice. The non-significant paths were deleted

first. The resultant model did not achieve a good fit either. The majority of the fit indices

did not show a good fit. Finally, the Monitoring component of the model was removed to

render the measurement model 4 (see Figure 4). It should be noted that all of the

standardised paths between observed and /or latent variables were significant (p < .001).

742 Developing and validating a metacognitive writing questionnaire for EFL learners

Figure 3: Regulation of cognition model (standardised estimates)

The model fit indices demonstrated that the revised model provided a good fit for the

data and the chi-square test was significant (χ

2

(45) = 284.60, p < .05). The ratios of the

chi-square over the degree of freedom (1.72 < 3) also indicated that the model enjoyed a

good fit. The RMSEA value of .033 and its 95 percent confidence intervals (.030 and .045)

were all lower than .05, another indication that the fit of the model was adequate.

Furthermore, the p-close fit value was .998 (> .05) suggesting a good fit for the knowledge

of cognition.

Farahian 743

Figure 4: Revised regulation of cognition model (standardised estimates)

Trait structures of total model knowledge and regulation of cognition

The combination of the final models of knowledge of cognition (Figures 3 and 4) and

regulation of cognition (Figures 2 and 4) is displayed below in standardised units (Figure

5). The two questionnaires are hypothesised to measure a higher order latent variable, i.e.,

metacognitive awareness of writing (MAW). All the paths connecting the latent and or

observed variables enjoy statistical significance (p < .001).

The MAW model fit indices (Table 2) implied a good fit. As illustrated in Table 1, the

ratios of the chi-square over the degree of freedom (2.08 < 3) indicated a good fit. The

RMSEA value of .046 and its 95 percent confidence intervals (.042 and .049) were all

lower than .05; another evidence for the fit of the model. The p-close fit value of .975 (>

.05) was also indicative of fit of the MAW model.

Table 2: Model fit indices - metacognitive awareness of writing - final revision

Model fit

Value

Recommended level

Chi-square

1214.47 (584), p < .05

p < .05

Ratio of χ

2

over d.f.

2.08

< 3

GFI

.88

>=.90

AGFI

.86

>=.90

RMR

.23

<.05

RMSEA

.046

< .05

95% CIV RMSEA

(.042 to .049)

< .05

p-close for RMSEA

.975

>.05

CFI

.92

>.95

744 Developing and validating a metacognitive writing questionnaire for EFL learners

Figure 5: Revised model for knowledge of and regulation of cognition

Since the result obtained from EFA did not yield reliable factors, CFA was run to

demonstrate the construct validity of the MAWQ and refined the proposed model. Thus,

as in EFA, first the trait structure of knowledge and regulation of cognition was sought

separately. Later, the trait structure of the whole model was explored. Based on goodness

of fit statistics, the hypothesised models were modified and the items which did not have

Farahian 745

significant observed variables were dropped. Regarding the goodness of fit of the final

model, all model fit indices were satisfactory. Accordingly, a questionnaire (see the

Appendix) with 36 items emerged.

Conclusion

The findings are congruent with the account of metacognition with two general

components (Brown, 1987; Jacobs & Paris, 1987). Although these two components are

interrelated (Brown, 1987; Schraw, 1998), it was found that knowledge and control are

two distinct elements. Moreover, the findings supported the 36 item questionnaire which

can measure metacognitive awareness of Iranian EFL learners.

Additionally, the findings of the study also suggest that three sub-components of

metacognitive knowledge - declarative, procedural, and conditional (Shraw & Moshman,

1995) - well suit Iranian EFL learners; however, based on the findings, apart from

individual’s self-concept reported by Ruan (2014) as a variable affecting person

knowledge, students’ beliefs and opinions regarding the act of composing is part of

person knowledge. Thus, it can be assumed that students’ beliefs with regard to what is

effective writing affects their metacognitive awareness.

Although the results partially supported the literature on metacognition (Schraw &

Dennison 1994; Schraw & Mushman, 1995), removing monitoring and evaluation ran

counter to the expectations, thus, another research study could be conducted to

administer the obtained questionnaire in the same context. As such, future research is

needed to refine the model and identify the nature of the relationships among the factors.

Additionally, further research is needed to interview a number of EFL teachers and seek

their views about the utility of the MAWQ. The follow up study may enquire if they see

the new scale as a tool which provides them with enabling insights into their own

teaching.

The present study makes theoretical and pedagogical contributions to the field of

educational psychology and second language acquisition. First of all, despite the fact that

in recent years few research studies (e.g., Ruan, 2014; Schraw & Dennison, 1994; Sperling

et al., 2002; Vandergrift et al., 2006) have attempted to contribute to a more coherent

picture of the construct of metacognition, to the best of author’s knowledge, no attempt

has been made to present a comprehensive model of metacognitive in foreign language

learning. Thus, the model presented here may contribute to a better understanding of the

nature of metacognition in a domain-specific area as foreign language writing. At the same

time, the presented model may inform research in the area of metacognition, since due to

the abstract nature of metacognitive awareness its operationalisation presents a more

coherent view of the construct. This may contribute to a further consistency in

metacognitive research and at the same time prepare the cornerstone for further

exploration of metacognitive awareness in EFL settings.

746 Developing and validating a metacognitive writing questionnaire for EFL learners

It should be kept in mind that Iranian EFL student have gone through an educational

system in which the general approach toward writing has been predominantly a product-

oriented approach. In addition, instructors have often felt that it was sufficient to provide

students with lexical or grammatical knowledge of the writing task. Such an orientation

has led to the neglect of the process of writing in EFL courses. As a result, many Iranian

EFL learners have failed at acquiring writing skills because they have little or no awareness

of the complexity of writing as a cognitive task. As to pedagogical implications, the

findings may help teachers and students become more familiar with the process of EFL

writing, especially the higher order processes of writing.

It has been argued that metacognition is culture bound and that different educational

environments result in differences in metacognition (Angelova, 2001; Hacker & Boll,

2004). Therefore, while on the one hand selecting participants from one province of Iran

may have resulted in the homogeneity of the sample, on the other hand this reduced the

generalisability of the findings to other EFL contexts. Further research is needed to

randomly select participants and administer the questionnaire in other EFL contexts.

Finally, while providing answers to some questions, and, at the same time, raising new

questions, this study makes a small contribution to the research in the area of

metacognition in EFL writing. Moreover, it generates a new outlook to metacognition in

EFL learning and provides new perspectives for the research on EFL writing. However, it

should not be forgotten that despite its psychometric properties, the MAWQ like any

other scale can be considered as only one source of information regarding EFL students’

metacognitive awareness.

References

Angelova, M. (2001). Metacognitive knowledge in EFL writing. Academic Exchange

Quarterly, 5(3), 78-83. https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1G1-

80679259/metacognitive-knowledge-in-efl-writing-language

Blasco, J. A. (2016). The relationship between writing anxiety, writing self-efficacy, and

Spanish EFL students’ use of metacognitive writing strategies: a case study. Journal of

English Studies, 14, 7-45.

https://publicaciones.unirioja.es/ojs/index.php/jes/article/view/3069

Brown, A. (1987). Metacognition, executive control, self-regulation, and other more

mysterious mechanisms. In F. Weinert & R. Kluwe (Eds.), Metacognition, motivation, and

understanding (pp. 65-116). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Brown, A. L., Bransford, J. D., Ferrara, R. A. & Campione, J. C. (1983). Learning,

remembering, and understanding. In P. H. Mussen (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology

(4th ed., Vol. III, pp. 77-166). New York: Wiley.

Farahian, M. (2015). Assessing EFL learners’ writing metacognitive awareness. Journal of

Language and Linguistic Studies, 11(2), 39-51.

http://www.jlls.org/index.php/jlls/article/view/396/218

Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive-

developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906-911.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.906

Farahian 747

Flavell, J. H. (1987). Speculation about the nature and development of metacognition. In

F. Weinert & R. Kluwe (Eds.), Metacognition, motivation, and understanding (pp. 21-29).

Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Fox, E. & Riconscente, M. (2008). Metacognition and self-regulation in James, Piaget and

Vygotsky. Educational Psychology Review, 20(4), 373-389.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10648-008-9079-2

Gustilo, L. E. & Magno, C. (2015). Explaining L2 writing performance through a chain of

predictors: A SEM approach. 3L: The Southeast Asian Journal of English Language Studies,

21(2), 115-130. http://ejournals.ukm.my/3l/article/view/8787

Hacker, D. J. & Bol, L. (2004). Metacognitive theory: Considering the social-cognitive

influences. In D. M. McInerney & S. van Etten (Eds.), Big theories revisited: Research on

sociocultural influences on motivation and learning (pp. 275-297). Greenwich, CT: Information

Age Publishing.

Hacker, D. J., Keener, M. C. & Kircher, J. C. (2009). Writing is applied metacognition. In

D. J. Hacker, J. Dunlosky & A. C. Graesser (Eds.), Handbook of metacognition in education

(pp. 154-172). New York: Routledge.

Hawkins, R. E. (2007). Classifying and characterizing student writers' metacognition: A social

cognitive ethnography. PhD dissertation, Southern Illinois University.

https://search.proquest.com/openview/1198827f27d2ed92cdfe868aa7899990/1?pq-

origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

Hayes, J. & Flower, L. (1980). Identifying the organization of writing processes. In L.

Gregg & E. Steinberg (Eds.), Cognitive processes in writing (pp. 3-30). Hillsdale, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum.

Kasper, L. F. (1997). Assessing the metacognitive growth of ESL student writers. TESL-

EJ, 3(1), 1-20. http://www.tesl-ej.org/wordpress/issues/volume3/ej09/ej09a1/

Maftoon, P., Birjandi, P. & Farahian, M. (2014). Investigating Iranian EFL learners’ writing

metacognitive awareness. International Journal of Research Studies in Education, 3(5), 37-52.

https://doi.org/10.5861/ijrse.2014.896

Mokhtari, K. & Richards, C. A. (2002). Assessing students’ metacognitive awareness of

reading strategies. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(2), 249-259.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.94.2.249

Negretti, R. & Kuteeva, M. (2011). Fostering metacognitive genre awareness in L2

academic reading and writing: A case study of pre-service English teachers. Journal of

Second Language Writing, 20(2), 95-110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2011.02.002

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks,

CA: SAGE.

Ruan, Z. (2014). Metacognitive awareness of EFL student writers in a Chinese ELT

context. Language Awareness, 23(1-2), 76-91.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2013.863901

Schraw, G. (1998). On the development of adult metacognition. In M. C. Smith & T.

Pourchot (Eds.), Adult learning and development: Perspectives from educational psychology (pp.

89-108). Mawah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Schraw, G. & Dennison, R. S. (1994). Assessing metacognitive awareness. Contemporary

Educational Psychology, 19(4), 460-475. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1994.1033

Schraw, G. & Moshman, D. (1995). Metacognitive theories. Educational Psychology Review,

7(4), 351-371. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF02212307

748 Developing and validating a metacognitive writing questionnaire for EFL learners

Statistics Solutions (n.d.). AMOS. http://www.statisticssolutions.com/amos/

Vandergrift, L., Goh, C. C. M., Mareschal, C. J. & Tafaghodtari, M. H. (2006). The

metacognitive awareness listening questionnaire: Development and validation. Language

Learning, 56(3), 431-462. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-

9922.2006.00373.x/abstract

Victori, M. (1999). An analysis of writing knowledge in EFL composing: A case study of

two effective and two less effective writers. System, 27(4), 537-555.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(99)00049-4

Wenden, A. L. (1998). Metacognitive knowledge and language learning. Applied Linguistics,

19(4), 515-537. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/19.4.515

Yanyan, Z. (2010). Investigating the role of metacognitive knowledge in English writing.

HKBU Papers in Applied Language Studies, 14, 25-46.

http://lc.hkbu.edu.hk/book/pdf/v14_02.pdf

Yeh, H. C. (2014). Facilitating metacognitive processes of academic genre-based writing

using an online writing system. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 28(6), 479-498.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2014.881384

Zimmerman, B. J. & Bandura, A. (1994). Impact of self-regulatory influences on writing

course attainment. American Educational Research Journal, 3194), 845-62.

http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.3102/00028312031004845

Appendix: MAWQ (Metacognitive Awareness Writing

Questionnaire)

Items

Strongly

agree

Agree

No idea

Disagree

Strongly

disagree

1.

Writing in English makes me feel bad about

myself.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

2.

I think writing in English is more difficult

than reading, speaking, or listening in

English.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

3.

I believe a successful writer is born not

made.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

4.

Topic familiarity has a significant effect on

one’s writing output.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

5.

A skillful writer is familiar with writing

strategies (e.g., planning or revising the text).

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

6.

At every stage of writing, a skillful writer

avoids making error.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

7.

Dwelling on vocabulary items and grammar

interferes with getting the message across.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

8.

Word by word translation from first

language to English negatively affects one’s

ability in writing.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

9.

I am aware of different types of text types in

writing (e.g., expository, descriptive,

narrative).

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

Farahian 749

10.

I know that the necessary components of an

essay are introduction, body, and conclusion.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

11.

I am familiar with cohesive ties (e.g.,

therefore, as a result, firstly).

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

12.

I know what a coherent piece of writing is.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

13.

I am good at writing topic sentences.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

14.

I know what to do at each stage of writing.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

15.

I find myself applying writing strategies with

little difficulty.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

16.

I know how to develop an appropriate

introduction, body, and conclusion for my

essay.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

17.

I know when to use a writing strategy.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

18.

I know which writing strategy best serves the

purpose I have in my mind.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

19.

I know what to do when the writing

strategies I employ are not effective.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

20.

I know which problem in writing needs

much more attention than others.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

21.

Before I start to write, I prepare an outline.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

22.

I have frequent false starts since I do not

know how to begin.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

23.

Before I start to write, I find myself

visualising what I am going to write.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

24.

My initial planning is restricted to the

language resources (e.g., vocabulary,

grammar, expressions) I need to use in my

essay.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

25.

I set goals and sub-goals before writing (e.g.,

to satisfy the teacher, to be able to write

emails, to be a professional writer).

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

26.

I find myself resorting to fixed sets of

sentences I have in mind instead of creating

novel sentences.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

27.

At every stage of writing, I use my

background knowledge to create the

content.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

28.

I mainly focus on conveying the main

message rather than the details.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

29.

I automatically concentrate on both the

content and the language of the text.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

30.

I can effectively manage the time allocated

to writing.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

31.

I choose the right place and the right time in

order to write.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

32.

I use avoidance strategies (e.g. when I do not

know a certain vocabulary item or structure,

I avoid it).

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

33.

When I cannot write complicated sentences,

I develop other simple ones.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

750 Developing and validating a metacognitive writing questionnaire for EFL learners

34.

After I finish writing, I edit the content of my

paper.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

35.

If I do revision, I do it at the textual features

of the text (e.g., vocabulary, grammar,

spelling).

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

36.

If I do revision, I do it at both textual and

the content levels.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

Majid Farahian is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English Language

Teaching, College of Literature and Humanities, Kermanshah Branch, Islamic Azad

University (IAUKSH), Kermanshah, Iran. His main research interests are foreign

language writing, metacognitive awareness in FL writing, and the study of plagiarism in

EFL settings.

Email: farahian@iauksh.ac.ir

Please cite as: Farahian, M. (2017). Developing and validating a metacognitive writing

questionnaire for EFL learners. Issues in Educational Research, 27(4), 736-750.

http://www.iier.org.au/iier27/farahian.pdf